During the Russian Civil War, Lenin had ordered the acquisition of the peasant’s grain and livestock, losses which the peasantry could ill-afford; 85 per cent of the Soviet Union’s population lived off the land. He had also demanded the collectivisation of farms, where peasants were obliged to surrender their land and crops, and their livestock, machinery and labour to the village – for the supposed benefit of all. ‘Kulaks’, peasants perceived as better-off, were to be destroyed: killed or deported. In effect, the loosely-defined kulak could be a peasant with an extra cow or half an hectare and were often the more efficient farmers. Their destruction caused widespread devastation and eventually famine. In 1921, Lenin, realising his mistakes, had found suitable scapegoats but nonetheless compromised by introducing his ‘New Economic Policy’, in which he allowed the peasantry to sell their goods on the open market for profit to aid the Russian economy devastated by years of revolution and civil war.

In 1928, Stalin decided again to implement collectivisation. Whereas Lenin recognised it could take generations to achieve, Stalin aimed at five years and, in the more important agricultural areas, such as the Ukraine, within two. At first, he envisaged a voluntary process, but with the peasantry unwilling to respond to his call, collectivisation soon became compulsory. Anyone who resisted was to face the harshest penalties: ‘those who do not join the collectives are enemies of Soviet power’.

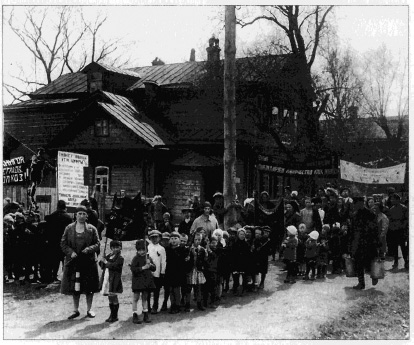

Village children parading under a banner, ‘we will liquidate the kulaks as a class’, c.1929

Stalin rarely visited the countryside: ‘He knew the country and agriculture only from films,’ said Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin’s successor, later in 1956, ‘and these films dressed up and beautified the existing situation in agriculture.’ Convinced that the kulaks were hoarding grain, Stalin declared, ‘The struggle for bread is the struggle for Socialism’. On 27 December 1929, six days after his official fiftieth birthday, he announced the ‘liquidation of the kulak as a class’. It was class warfare: kulaks were again to be shot or deported. Poorer peasants, resentful of the more prosperous ones, were encouraged and sometimes took delight in denouncing the kulaks, while those unwilling to join the collective were automatically labelled as kulak.

The Party sent out brigades of devotees to root out the kulaks, to ransack dwellings, confiscate their grain, and force villages into collectives – often at gunpoint. They had no knowledge of agriculture and no appreciation of the possible consequences of Stalin’s determination to coerce a huge rural population to fulfil his political objective.

The kulaks resorted to slaughtering their own cattle and destroying their equipment rather than see it disappear into the hands of the State. Many committed suicide, whole families killing themselves rather than face deportation. Orphaned children were shot. Many tried to flee to the cities and find employment there, causing insufferable strain on urban accommodation and food supply. Those deported found themselves crammed into cattle trucks with little food or water and sent thousands of miles to be consigned to a long stretch in the gulag or dumped in the inhospitable terrains of Siberia, where they were left without provisions or shelter.

Famine

Famine took hold. Vast areas were affected – most appallingly in the Ukraine, where millions (possibly up to ten million) died in Stalin’s manmade ‘Terror famine’, remembered in the Ukraine as the Holodomor, the ‘killing by hunger’. Victims resorted to eating tree bark and even cannibalism, with cases of adults killing and consuming their own children. In 1932, the party introduced the Law of Spikelets to protect State property, so called because those guilty of stealing even handfuls of grain or ‘spikelets’ were liable to punishment by death or deportation. Watchtowers were erected to ensure starving civilians adhered to the new law.

Stalin’s twin priority at this time was the success of his ‘First Five-Year-Plan’, introduced in 1928. To fund his overambitious industrial plan, Stalin exported millions of tonnes of grain – however, this was not surplus grain, but vitally needed grain.

Lenin had similarly caused a famine in the Volga region in 1920–21 but at least he finally acquiesced and allowed in foreign aid. Stalin refused to allow the world to see the result of his errors – no aid or relief was sought. Spreading ‘misinformation’ about the situation was punishable by deportation. Villages full of starving inhabitants were sealed off by roadblocks to prevent anyone getting in or out. When one Party member wrote to Stalin describing the horrific scenes of famine, Stalin admonished him for writing ‘fables’ and advised him that his writing skills would be better employed as a fiction writer.

Western dignitaries were shown around carefully-prepared collectives where well-fed and enthusiastic villagers exclaimed the joys of living in Stalin’s utopia. H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, and Sidney and Beatrice Webb, were among those who visited and came away singing to Stalin’s tune. One Welsh journalist, Gareth Jones, wrote the truth in a series of newspapers articles in 1933. Widely criticised by Western observers, Jones was banned by the Soviet Union from re-entering the country and met his death in suspicious circumstances while touring the Far East in August 1935.

‘Dizzy With Success’

Finally realising the process had gone too far, Stalin called a halt. In a Pravda article entitled ‘Dizzy With Success’, 2 March 1930, he gloried the rate of collectivisation as a ‘tremendous achievement’ but admitted that ‘some of our comrades have become dizzy with success and for the moment have lost clearness of mind and sobriety of vision.’ It was his usual way of scapegoating others for his excesses. Peasants, if they so wished, were allowed to leave their collectives. Eight million did so. But it was only a temporary lull – six months later, collectivisation and ‘dekulakization’ were reintroduced.