Karl Marx got very little right in his explanations of history and social structure. But he got some things half-right. Among them was the claim that the bourgeoisie played the leading role in the Industrial Revolution.

Marx borrowed the term bourgeoisie from the French, who used it to identify wealthy, urban commoners. He distorted the term to identify the bourgeoisie as the capitalist ruling class. In the Communist Manifesto (1848), Marx and Engels credited this group with having produced the Industrial Revolution: “The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together.” The wealth the bourgeoisie had produced, they said, would be sufficient to fund the coming communist state—although, to achieve this state, the people (the proletariat) must destroy the bourgeoisie. According to Marx, this was inevitable: “What the bourgeoisie … produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable.”

Of course, when Marxist regimes appeared in the world, they turned out to be nothing more than the same old command economies. The only difference was that, in comparison with Joseph Stalin and Mao Tse-tung, the Ottoman sultans and the Egyptian pharaohs seemed enlightened and restrained tyrants.

Still, Marx was correct to credit the bourgeoisie—that is, a newly respectable upper middle class—with the Industrial Revolution. The singular aspect of bourgeois societies is the belief that status and power should be achieved through merit rather than through inheritance. Innovation is valued and rewarded. Consequently, the two primary supports of bourgeois societies are education and liberty.

Bourgeois societies did not rise everywhere at the same time. Initially this class emerged only in the Netherlands and, especially, Britain. In his famous study The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith (1723–1790) referred to Britain as “a nation of shopkeepers.”1 Therein lies the answer to the question of why Britain led the way in the Industrial Revolution as well as being unusually prolific in science. In Britain there was sufficient liberty for merit and ambition to prevail, creating a society dominated not by a hereditary nobility but by “strivers” and “achievers.” The rise of the bourgeoisie in Britain was accelerated and solidified by a flood of younger sons of the nobility into its ranks.

Compared with Britain, the Continental nations lagged in liberty and education—and achieved modernity later and less fully. Across the Atlantic, the United States was a bourgeois society from the beginning, and it quickly caught up with and then surpassed Britain in industrial and economic development.

To fully explain why the Industrial Revolution began in Britain, it is necessary to explain why it became a bourgeois society.

Liberty and Property Rights

When property rights are not secure, it may be pointless to be more productive. If, for example, the lord leaves the peasant the same bare minimum no matter how good the crop, it is better for the peasant to conceal some of the crop than to improve the yield. That has been the state of affairs in most societies throughout history—not just for the peasantry but for nearly everyone else as well. Recall from chapter 14 that Ali Pasha, the Ottoman commander at the Battle of Lepanto, was afraid to leave his fortune at home, even though he was the sultan’s brother-in-law. The Ottoman sultan, like the emperor of China, claimed ownership of everything; whenever either of them needed funds, “confiscation of the property of wealthy subjects was entirely in order,” as the economist William K. Baumol observed.2 And that is precisely why the rulers of the great empires were rich but their societies were poor and unproductive. It also is precisely why the Industrial Revolution took place in Britain, not in China or even in France.

Recall from chapter 9 that the Magna Carta guaranteed the property rights not only of British citizens but even of foreign merchants. Hence, unlike their counterparts in China, iron industrialists in England were secure against government seizure. Writing in 1776, the same year that James Watt perfected his steam engine, Adam Smith explained why liberty and secure property rights produce progress:

That security which the laws of Great Britain give to every man that he shall enjoy the fruits of his own labour, is alone sufficient to make any country flourish.… The natural effort of every individual is to better his own condition, when suffered to exert itself with freedom and security, is so powerful a principle, that it is alone, and without any assistance, … capable of carrying on the society to wealth and prosperity.… In Great Britain industry is perfectly secure; and though it is far from being perfectly free, it is as free or freer than in any other part of Europe.3

In contrast, taxes were so confiscatory in France that, as Smith pointed out, the French farmer “was afraid to have a good team of horses or oxen, but endeavors to cultivate with the meanest and most wretched instruments of husbandry that he can,” so that he will appear poor to the tax collector.4 Writing to a friend back in France during a visit to England, Voltaire expressed his surprise that the British farmer “is not afraid to increase the number of his cattle, or to cover his roof with tile, lest his taxes be raised next year.”5

High Labor Costs

An essential element in the Industrial Revolution was the productivity of the British farmer, which freed more well-fed laborers for industrial employment. French farmers, for example, were less productive—to the point that during the eighteenth century as many as 20 percent of the French were so poorly fed that they couldn’t do even light work for more three hours a day.6 In the late 1700s the average British soldier was four inches taller than the average French soldier.7

A related factor was the high cost of labor in Britain. Recall that although the Romans were fully aware of water power, they made almost no use of it. Why not? Because it was cheaper to buy slaves to do such tasks as grinding grain than to invest in building and maintaining waterwheels.

British firms, in contrast, often found it cheaper to invest in machines to reduce the need for labor than to pay laborers to do what the machines could do. In 1775 laborers in London earned about twelve times as much as did laborers in Delhi, four times as much as in Beijing, Florence, or Vienna, and a third higher than in Amsterdam.8

The elevated cost of British labor began with the industrial and economic developments of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (discussed in chapter 9). These developments created high demand for British products, especially its woolens, on the international market. The British quickly realized that while their luxury woolens were popular with wealthy Europeans, there was far more money to be made in high-volume, inexpensive goods sold to the mass market. As a French nobleman noted, “The English have the wit to make things for the people, rather than for the rich.”9 By successfully developing a mass market, the British faced the constant need to expand production, and that created competition for workers among British firms. Wages were further raised by the “putting-out” system in the woolen industry (the major British industry in this era), which allowed work to be performed in the home rather than by a gathered labor force. Management saved on the costs of providing the facilities and supervising a workforce, and it passed on part of these savings to workers to attract good laborers.

High wages begat even higher wages because they led to lower fertility rates prior to 1700—and where fertility rates are low, the demand for potential workers tends to exceed the supply. As Robert C. Allen wrote in his economic history of the British Industrial Revolution, the high wages permitted “young people—and young women in particular—[to] support themselves apart from their parents and control their lives and marriages. Women put off marriage until it suited them, and they found the right partner.”10 The average British woman married at about twenty-six, compared with the prevalence of teenage marriages elsewhere in Europe.11 While wages in Britain increased, prices remained about the same as elsewhere, which made British workers better consumers than their counterparts on the Continent.12

For all these reasons, high wages made it profitable for British industries to invest in labor-saving devices, which helped spur the Industrial Revolution.

Cheap Energy

As noted in chapter 9, Britain was well ahead of the rest of the world in switching from wood to coal as its primary fuel. Because coal generated much higher temperatures than wood, the transition had many important consequences for the metal industries. Britain’s adoption of coal also prompted innovations in mining technology and in transportation that made Britain by far the world’s leading producer of coal.13 In the 1560s Britain produced 227,000 tons of coal per year; by 1750 that had risen to 5.2 million tons per year; by 1800 coal production exceeded 15 million tons a year.14 Consequently, coal was far cheaper in Britain than anywhere else. This, quite literally, fueled the Industrial Revolution.15

Embracing Commerce

In addition to having secure property, high wages, and cheap energy, British culture was favorable to commerce. That made Britain different from most other societies throughout history, which generally regarded commercial activities as degrading.

In his Politics, Aristotle noted that although it might be useful to explore “the various forms of acquisition” of wealth, it “would be in poor taste” to do so. He condemned commerce as unnatural, unnecessary, and inconsistent with “human virtue.”16 Plutarch thought it especially virtuous that Archimedes, one of the shining lights of ancient inventiveness, regarded all practical enterprises “as ignoble and vulgar.”17 Cicero wrote with contempt that “there is nothing noble about a workshop.”18

As for the Romans, they were especially acquisitive but considered participation in industry or commerce to be degrading.19 The Emperor Constantius declared, “Let no one aspire to enjoy any standing or rank who is of the lowest merchants, money-changers, lowly officers or foul agents of … assorted disgraceful professions.”20 Freedmen were largely responsible for commercial and industrial activities in Rome. Having been slaves, they were already stigmatized and had no status at risk in such enterprises.21 Freedmen were, of course, at the mercy of the state, and their property was insecure.

Things were not much different in Byzantium. In 829 Emperor Theophilus watched a beautiful merchant ship sail into the harbor of Constantinople. When he asked who owned the ship, he was enraged to learn that it belonged to his wife. He snarled at her, “God made me an emperor and you would make me a ship captain!” He had the ship burned at once.22

In China, as seen in previous chapters, the Mandarins held commerce in such contempt that they outlawed significant commercial enterprises.

Similar attitudes prevailed in many parts of Europe. In 1756 the Abbé Coyer wrote: “The Merchant perceives no luster in his career, & if he wants to succeed in what is called in France being something, he must give it up. This … does a lot of damage. In order to be something, a large part of the Nobility remains nothing.”23

Contrast all this with the frequent joint financial ventures Queen Elizabeth entered into with merchant voyagers and privateers. Elizabeth reigned during a major transformation of the British class system—a transformation that supplied the innovators, inventors, and managers who produced the Industrial Revolution.

This transformation resulted in part because the British embraced trade with the New World. Sophisticated recent research has validated the traditional view that the rise of the bourgeoisie occurred first in those European nations most involved in Atlantic trade and having relatively free (nonabsolutist) political institutions.24 That is why Britain and the Netherlands emerged as the first bourgeois societies, while absolutist monarchies prevailed in the other Atlantic trading nations: Spain, Portugal, and France. Why absolutist states limited the rise of the bourgeois is not difficult to explain. By imposing a command economy, the state also sustained the nobility’s status and power—and their contempt for commerce. Moreover, these states actually impeded commerce. In France, for example, nearly every commercial enterprise operated under a monopoly license purchased from the state; there was no competition.25

But why should Atlantic trade have spurred the rise of the bourgeoisie in nonabsolutist nations? Three factors were involved. First, vigorous Atlantic trade expanded and strengthened those merchant groups involved directly or indirectly in this trade. Second, as these groups grew and became rich, they gathered sufficient power to demand changes, including even more secure property rights, that expanded their ranks. The third factor might have been the most important one: by virtue of their success and influence, the bourgeois earned respect and dignity.26

Claims27 that the rise of the West was funded by the profits of trade with the New World—from colonialism and slavery—are refuted by the simple fact that these profits were too small to have made a substantial contribution to the economic growth of western Europe.28 These profits were, however, sufficient to make groups of merchants “very rich by the standards of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe, and typically politically and socially very powerful,” in the words of the historian J. V. Beckett.29

MIT economist Daron Acemoglu and his colleagues empirically confirmed an immense historical literature proposing that from 1500 through 1800:

• |

All Atlantic port cities grew much faster than did inland cities or ports on the Mediterranean. These cities were dominated by merchants engaged in import-export trading with the New World. |

• |

Rapid urbanization took place in Britain and the Netherlands but much less so in France and Spain, and there was a strong correlation between urbanization and per capita income, for in cities commerce was king. |

• |

Legal changes that greatly improved property rights (including patent laws) took place in Britain and the Netherlands but much less so or not at all elsewhere. |

• |

Merchants came to dominate the Parliament in Britain and the Dutch States-General. |

But in Britain, it was not just the rising bourgeoisie that proved open to commerce. The nobility displayed little of the contempt for commercial activities that their peers on the Continent did. For one thing, British nobles were much less inclined to live in London and spend their days at court (in part because several sixteenth-century kings had taken measures to deter the aristocracy from spending time at court).30 In contrast, most of the French nobility lived in Paris and seldom visited their estates. Therefore, rather than being absent landlords, most of the British nobility took an active role in administering their lands. In this sense they actually “worked” for their livings. Moreover, they were fully involved in the market economy, their incomes being governed by prices for their crops, livestock, wool, and other products such as minerals. In fact, according to scholar Colin Mooers, an estimated “two-thirds of the peerage, in the period 1560–1640, was engaged in colonial, trading or industrial enterprises.”31

An equally important aspect of the British nobility was that younger sons “automatically descended into the gentry,” as Beckett pointed out. They could use the “courtesy title ‘lord,’ but only for themselves, not for their children.”32 For example, Winston Churchill’s father was Lord Randolph Churchill because he was the third son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, but his son Winston could not call himself a lord. Thus did the overwhelming number of noble English offspring “disappear” into the population of commoners. Nor could younger sons expect to live off the family lands (as was typical on the Continent). Rather, as Beckett noted, many younger sons received a “cash payment to set themselves up as best they could.”33 In each generation, then, a large number of younger sons of the nobility were forced to find gainful occupations and professions. They not only staffed the church and the officer corps but also were active in law, academia, banking, mining, manufacturing, and other forms of commerce. The flood of well- educated and well- connected young men into these occupations brought with them substantial prestige and power.

The Expansion of British Education

The rise of the bourgeoisie was accompanied by what Lawrence Stone called an “educational revolution in England.”34

As noted in chapter 15, massive educational changes began in the mid-sixteenth century. First was the establishment of thousands of “petty schools” for the purpose of teaching “basic literacy to the bulk of the population.”35 Nothing like this had ever been attempted before, anywhere. These efforts were financed not by the government but by a huge number of private bequests for the establishment of local schools to provide free instruction. By about 1640 England had a petty school for every 4,400 people, or “one approximately every twelve miles.”36 Also free were schools that taught not only reading but also grammar, writing, arithmetic, and bookkeeping. And, of course, there were the sophisticated “grammar schools,” meant to prepare students for entry into the universities and the Inns of Court (law school). Perhaps surprisingly, the grammar schools were not limited to the children of the aristocracy. For example, from 1636 to 1639 Norwich grammar school sent on to the University of Cambridge the sons of “one esquire, four gentlemen, two clergymen, a doctor, a merchant, an attorney, a weaver, a carpenter, a fishmonger, two staymakers and two drapers.”37

As that list attests, in this era many from humble origins went to the great universities of Oxford and Cambridge. In fact, at no time between 1560 and 1629 were the majority of university students classified as “gentlemen.”38 This era saw a dramatic expansion in the enrollment of sons of the bourgeoisie. For example, the sons of merchants and tradesmen accounted for 6 percent of the students at Caius College, Cambridge, in 1580–90; by 1620–29 the figure had increased to 23 percent. Similarly, enrollment by the sons of clergy and the professions grew from 5 percent to 19 percent. Hence, by 1620–29, nearly half (42 percent) of the students were from the bourgeoisie.39

By 1630, well before the takeoff of the Industrial Revolution, Britain had by far the best-educated population in the world. Furthermore, large numbers of those involved in industry and commerce had attended the elite universities, forming a critical mass of educated leaders to launch the Industrial Revolution. A remarkable study by the historian François Crouzet, based on 226 founders of large industrial firms in Britain from 1750 to 1850, revealed that 9 percent were the sons of aristocrats and 60 percent were the sons of the bourgeoisie. A similar study by the sociologist Reinhard Bendix, based on 132 leading industrialists from 1750 to 1850, reported that two-thirds were from families already well established in business.40

The American “Miracle”

When the Industrial Revolution began in Britain in about 1750, North America had hardly any manufacturing, aside from a large shipbuilding industry based on plentiful local supplies of timber and other materials (in 1773 American shipyards built 638 oceangoing vessels).41 Ships aside, manufacturing in America was limited to small workshops making items such as shoes, horse harnesses, nails, pails, and simple hand tools for the local market. Only the many little gunsmith shops, dedicated to fabricating the newly invented rifle, could compete with British goods in terms of quality. Nearly everything else in the way of manufactured goods was imported from England.

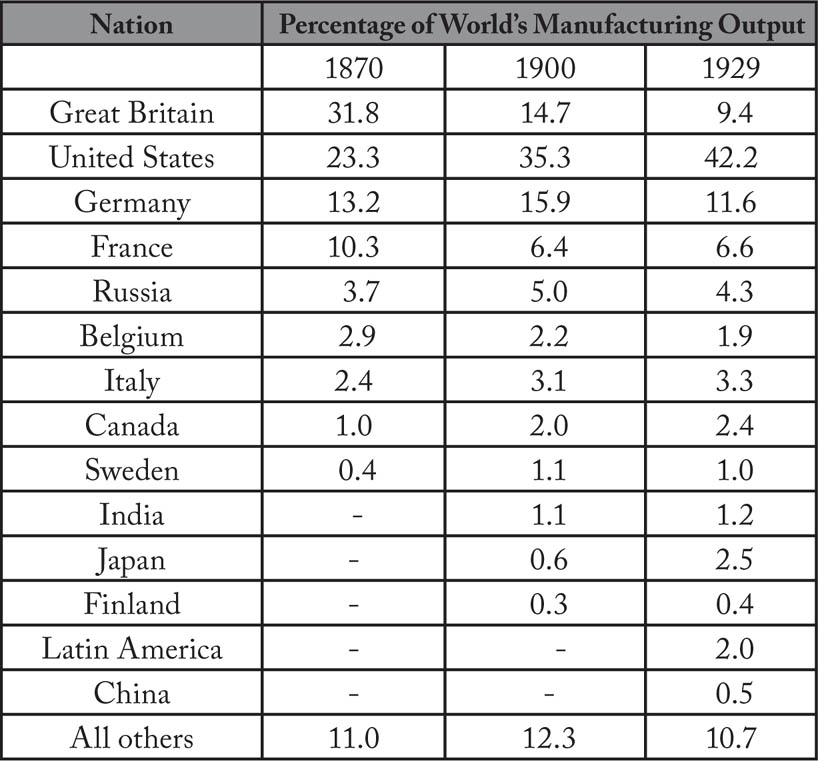

A century later the United States was catching up with Britain as a manufacturing power, and in fact the Americans soon surpassed the British and everyone else, as can be seen in table 17–1. In 1870 Great Britain produced about a third (31.8 percent) of all the world’s manufactured goods and the United States produced about a quarter (23.3 percent). By 1900 the United States was producing more than a third (35.3 percent) of all the world’s manufacturing output, compared with 14.7 percent produced by Great Britain and 15.9 percent by Germany. By 1929 the United States dwarfed the world as a manufacturing power, producing 42.2 percent of all goods, compared with Germany’s 11.6 percent and Britain’s 9.4.

This “miracle” of production was possible only because America had also forged ahead in the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, during the nineteenth century it seemed as if all the inventors lived in the United States.42

Why had this occurred? For all the same reasons that the Industrial Revolution had originated in Britain—political freedom, secure property rights, high wages, cheap energy, and a highly educated population—plus a plenitude of resources and raw materials and a huge, rapidly growing domestic market. In fact, by early in the nineteenth century, the United States surpassed Britain in all these crucial factors.

Property and Patents

The early American colonies came under English common law. Therefore individuals had an unlimited right to property that they had legally obtained, and not even the state could abridge that right without adequate compensation. Eventually that became the basis of American property law as well. Thus, the state could not seize iron foundries as had taken place in China, although it could purchase them should that seem desirable—as the socialist government of Britain did when it nationalized most basic industries right after World War II (until government control of these industries proved so unprofitable that they were transformed back into private companies).

Table 17–1: Percentage Shares of the World’s Manufacturing Output

Source: League of Nations, 1945

But this approach to property law was inadequate for protecting inventions and other forms of intellectual property. Consider the steam engine. Obviously, James Watt owned the steam engine he had constructed—it was his personal property and to steal it would have been a crime. But what if someone made an exact copy? Was it that person’s? If so, then how could Watt or any other inventor benefit from inventing? The solution was to grant a patent on inventions. Watt, for example, secured the exclusive right to ownership of all steam engines based on his principles for a number of years, including the right to sell, rent, license, or otherwise exploit that invention. The British Crown had initially granted patents, but the government formalized the process during the reign of Queen Anne (1702–1714), requiring applicants to submit a full description of their invention.

The American Founders regarded patent rights as so important that they wrote them into the Constitution: Article I, Section 8, states: “The Congress shall have power … to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” In keeping with this mandate, in 1790 Congress passed the U.S. Patent Act, which gave inventors an exclusive right to their inventions for a period of fourteen years. This was later amended to twenty-one years. Initially few applied for patents—only fifty-five were issued between 1790 and 1793. But by 1836 ten thousand patents had been registered. Then came an inventive explosion, and by 1911 one million patents had been granted. Among them were patents covering the invention of electric lightbulbs, movies, sound recordings, telephones, and the zipper.

Although it has often been overlooked, American laws concerning bankruptcy also facilitated industrial development. In Britain and most of Europe, laws concerning debts were brutal: in Britain those unable to pay their debts were sentenced to debtors’ prison, from where “they could scarcely repay their obligations let alone start new careers,” the historian Maury Klein noted. But America had no debtors’ prisons, and the law limited legal liabilities sufficiently “to give debtors enough breathing space to survive their downfall and get back into the game.”43 Many famous American industrialists and inventors survived early failures. More than that, entrepreneurs dared to take risks.

High Wages

If wages were high in Britain, they were towering in America. American wages were so high because employers had to compete with the exceptional opportunities of self-employment in order to attract adequate numbers of qualified workers. Alexander Hamilton explained shortly after the American Revolution, “The facility with which the less independent condition of an artisan can be exchanged for the more independent condition of a farmer … conspire[s] to produce, and, for a length of time, must continue to occasion, a scarcity of hands for manufacturing occupation, and dearness of labour generally.”44 Good farmland was so abundant and so cheap that even those who arrived in America without any funds could, in several years, save enough to buy and stock a good farm. Consider that in the 1820s the federal government sold good land for $1.25 an acre while wages for skilled labor amounted to between $1.25 and $2 a day.45 Consider, too, that in America there were no mandatory church tithes, and taxes were low.

Given higher labor costs, how could American manufacturers possibly compete on price? Through better technology. American industrialists eagerly embraced promising new technology if they anticipated a sufficient increase in worker productivity. For if workers equipped with a new technology could produce a sufficient amount more than could less mechanized workers in Europe, this reduced the relative cost of American labor per item. Technology made it irrelevant that American workers were paid, say, three times as much per hour as European workers (as they often were), when they produced five or six times as much per hour. That increased productivity offset both their own higher wages and the capital investments their employers made in new technology. Throughout the nineteenth century Americans led the way in developing and adopting new techniques and technologies. And they did so without provoking the reactionary labor opposition to innovation that nineteenth-century British capitalists so often faced—no Luddites smashed machines in the United States. Why not? Because, given the constant shortage of labor, American manufacturers competed with one another for workers and used a significant portion of their productivity gains to increase wages and to offer more attractive conditions.

Worker productivity was the basis for the incredible growth of American manufacturing shown in table 17–1, and why it came largely at the expense of the British. Americans were not more humane employers. They were more sophisticated capitalists who recognized that satisfied, productive workers are the greatest asset of all. This attitude toward labor brought many skilled and motivated British and European workers to America, and the expanded labor force sustained ever more industrial growth. Too many published discussions of the rise of American industry (especially in textbooks) denounce the “robber barons” and “plutocrats” for supposedly exploiting labor, and especially for abusing immigrants. Such tracts are anachronistic, comparing labor practices back then with those of today, almost as if factory latrines in 1850 should have had flush toilets. The proper comparison is between the situation of American labor and labor in the other industrializing nations in the same era.

In addition to being highly paid and equipped with the latest technology, American workers were notable in another way. They were far better educated than workers anywhere else in the world (excluding Canada).

During his 1818 visit to America, the English intellectual William Cobbett wrote home: “There are very few really ignorant men in America.… They have all been readers from their youth up” (his italics).46 From the earliest days of settlement the American colonists invested heavily in “human capital,” as modern economists would put it. And in this, religion played a primary role.

A major point of contention during the Reformation had to do with reading the Bible. For centuries the Church had thought the best way to avoid endless bickering about God’s Word was to encourage only well-trained theologians to read the Bible. To this end, the Church discouraged translations of the Bible into contemporary languages, thus tending to limit readership to those proficient in Latin or Greek, which even most clergy were not. In the days before the printing press there were so very few copies of the Bible that even most bishops did not have access to one. Consequently, the clergy learned about the Bible from secondary sources written to edify them and to provide them with suitable quotations for preaching. What the public knew about the Bible was only what their priests told them.

Then came the printing press. The Bible was the first book Gutenberg published. It was written in Latin, but soon Bibles were being printed in all the major “vulgar” languages (hence “vulgate” Bibles), making the Bible the first bestseller. As had been feared, conflict quickly arose as one reformer after another denounced various church teachings and activities as unbiblical. And the one doctrine most widely shared among the various dissenting Protestant movements was that everyone must consult scripture for themselves. So when the Pilgrims arrived in America in 1620, one of the first things they did was to concern themselves with educating their children.

In 1647 the Massachusetts Colony enacted a law asserting that all children must attend school.47 It required that in any township having fifty households, one person must be appointed to teach the children to read and write, with the teacher’s wages to be paid either by parents or by the inhabitants in general. In any township having a hundred or more households, a school must be established, “the master thereof being able to instruct youth so far as they may be fitted for the university.” Any community that failed to provide these educational services was to be fined “till they shall perform this order.” Other states followed suit, and free public schools became a fixture of American life. As the nation spread west, one-room schoolhouses were among the first things the settlers constructed (along with saloons, jails, and churches). Much the same took place in Canada, and by the end of the eighteenth century North America had by far the world’s most literate population.48

Notice that the Massachusetts law required that schoolmasters be qualified to prepare students for college. This was not as unreasonable as it might appear. A decade before they passed this law and only sixteen years after landing at Plymouth Rock, the Puritans had founded Harvard. This initiated three centuries of intense competition among the religious denominations to found their own colleges and universities. Prior to the Revolution ten institutions of higher learning had begun operating in the American colonies (compared with two in England). Of these, only the University of Pennsylvania, instituted by Benjamin Franklin to train businessmen, was not affiliated with a denomination. At least twenty more colleges were founded before 1800, including Georgetown University, founded by Jesuit scholars in 1789. During the next century literally hundreds of colleges and universities arose in the United States, and most of these also were of denominational origin (although many abandoned their denominational ties during the twentieth century). In 1890 two out of every hundred Americans age eighteen to twenty-four were enrolled in college; by 1920 this had risen to five of each hundred.49 At the time, nothing like this was going on anywhere else in the world.

Immigration

British North America grew at a remarkable rate from the very start. An estimated total of 600,000 people came from Britain between 1640 and 1760,50 and many others came from the Netherlands, France, Germany and other parts of Europe. The thirteen colonies had 1.6 million residents by 1760, more than 2.1 million in 1770, nearly 3 million by 1780, and 4 million by 1790.51 Given that Britain had a population of only about 8 million in the 1770s,52 the Revolutionary War was not as unequal as is often supposed. Moreover, by 1830 the United States population (13 million) was equal to that of Britain, and by 1850 it was far larger (23 million versus 17 million). In 1900 there were 76 million Americans and 32 million British.53 Hence, the American domestic market far surpassed that of Britain.

It also seems obvious that there was a powerful selective factor in who chose to come to America—the most ambitious and alert. In fact, immigrants were more likely to have come in pursuit of opportunity than to escape poverty. In his remarkable study based on immigration records, the celebrated historian Bernard Bailyn found that only 23 percent of immigrants from Britain from 1773 to 1776 were classified as laborers (most of them as servants), while half were classified as skilled craftsmen and another 20 percent as independent farmers. Aristocrats made up 2 percent of the British immigrants.54 This is consistent with the fact that younger sons of the nobility flocked to America.55 For example, during the last half of the nineteenth century membership in the Wyoming Stock Growers’ Association and its famous Cheyenne Club was dominated by younger sons of the British nobility as well as some titled Frenchmen and Germans.56 In the 1880s the largest ranch in the New Mexico Territory was owned by the youngest son of the 4th Marquis of Waterford.57

It seems significant that many of those involved in the explosion of American invention were immigrants. Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, was an immigrant from Scotland. Nikola Tesla, inventor of fluorescent lighting and of the alternating current (AC) electrical system, was raised in what is now Croatia. Thomas Edison’s two most important assistants were immigrants, one from Switzerland, the other from England.

Organized Invention

Accidental inventions are the stuff of dreams. Almost always, an inventor has set about trying to meet a significant need—often with a pretty good notion of how to do so. In fact, most “inventions” are actually improvements, and therefore the goal is well defined. In the wake of the Industrial Revolution, however, the flood of inventions gave rise to a new approach—a general commitment to invention and discovery per se. Leading this movement was Thomas Alva Edison (1847–1931). It could be said that Edison invented modern life, as he was responsible for the electric lightbulb, recorded sound, movies, the fluoroscope, great improvements to the telephone and telegraph, and basic research on electric railroads—a total of 1,093 patents.

But his most important contribution was to invent the research laboratory, with the primary mission of discovering that some new technology was needed and then launching research efforts to invent it. Edison’s laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey, was so successful at discovering needs and solutions that it became known as the “invention factory.” Today we take such an approach for granted. Most major companies survive by sustaining effective research and development divisions. Consumers expect new products and the constant improvement of old ones. That expectation, and the reality it reflects, is the epitome of modernity.

From Freedom to Prosperity

From early days, the rise of Western modernity was a function of freedom—freedom to innovate and freedom from confiscation of the fruits of one’s labors. When the Greeks were free they created a civilization advanced beyond anything else in the world. When Rome imposed its imperial rule all across the West, progress ceased for a millennium. The fall of Rome once again unleashed creativity and, for good and for ill, the fragmented and competing Europeans soon outdistanced the rest of the world, possessed not only of invincible military and naval might but also of superior economies and standards of living. All these factors combined to produce the Industrial Revolution, which subsequently changed life everywhere on earth.