4

Hong Kong Cinema in the Age of Neoliberalization and Mainlandization

Hong Kong SAR New Wave as a Cinema of Anxiety1

Mirana May Szeto and Yun-chung Chen

Nearly twenty years after Hong Kong returned to Chinese sovereignty, what are the major shifts in Hong Kong culture and cinema in relation to globalization? We will not privilege global / transnational cinemas or other frameworks of globalization studies to formulate these global–local relations. Instead, we argue that “neoliberalization” and “mainlandization” (Szeto and Chen 2011) have become more accurate terms to characterize actually existing problems of globalization that Hong Kong and the Hong Kong film industry are facing today. Their combined impact has drastically altered Hong Kong’s sense of reality, resulting in a different kind of anxiety. In analyzing recent works by established and emerging filmmakers, we discover that Hong Kong has aged depressingly from a culture of budding self-discovery in resistance to “disappearance” and “reverse hallucination” (Abbas 1997: 6), into a middle-aged culture “lost in transition” (Chu 2013), embarrassingly inhibited by blocked horizons and anxious about not moving on. To dovetail this point, we think that Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster (2013) is exactly a comeback statement by a Hong Kong New Wave / Second Wave grandmaster, after an embarrassing decade-long mid-career crisis. His silence in face of a post 1997 Hong Kong he no longer knows how to represent is poignantly echoed by other baby-boomer directors like Fruit Chan. The Midnight After (2014), Chan’s first feature film on Hong Kong after a similarly long hiatus, is about a van-load of passengers emerging from Lion Rock Tunnel2 not knowing what happened to Hong Kong before and what life will become afterwards. Disjointed from historical time and landed in an uncannily deserted hometown, without familiar time and space to anchor subjectivity, can living in Hong Kong mean anything anymore? This is “lost in transition” anxiety par excellence.

Arguably, Hong Kong culture is still a culture in crisis (Cheung and Chu 2004: xv). But is crisis still a useful concept if it is used to describe a constant state of affairs? Is this about crisis management, or management of status quo by way of crisis?

The younger generations, however, are becoming impatient about this extended mid-life crisis and its procrastinatory identity politics of ambiguity, deferral, and “disappearance.” To them, Hong Kong has been “in crisis” and “lost in transition” for thirty years, since the 1984 signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration, without seeing any end to this longue durée. It is as long as, if not longer than, their entire lifetime. To them, Hong Kong ought not to defer facing the real any longer; it should find ways to deal with this embarrassing state of anxiety, of symptomatic inhibition (Lacan 2014: 77). All other planes have departed, but passengers of flight Hong Kong are still in the transit hall waiting. Seriously, being stuck in limbo / bardo for thirty years is not the temporal-spatial order of mortals. It is the condition of the spectral and the living dead, as Juno Mak’s directorial debut, Rigor Mortis (2013) threateningly certify. Mak, born in 1984, flatly says about his film: “There wasn’t room for me. … It’s a story about middle-aged people dealing with ageing” (Time Out 2013). This film, together with Cold War (2012), the directorial debut of Longman Leung and Sunny Luk, a film about generational tug-of-war, are representative of what we call Hong Kong SAR New Wave cinema (Szeto and Chen 2012). This cinema exemplifies definitively new diagnoses and approaches to Hong Kong. Together with its new generation of post-80s and post-90s (born after 1980 and 1990) audience, the SAR New Wave has decided to take on Hong Kong’s anxiety in all sorts of new ways.

However, despite the different ways in which the baby-boomer Hong Kong New Wave / Second Wave and the younger SAR New Wave respond to the altered conditions of Hong Kong today, they converge to reconfigure post 1997 Hong Kong SAR cinema as a cinema of anxiety, anxiety being the “Signal of the Real” and “Cause of Desire” (Lacan 2014: 157, 100) in the Lacanian sense. This cinema signals the real in the imaginary space of cinema and provokes the anxieties that cause the desire for analysis of the Symbolic Order / Other (e.g. of Hong Kong, China) and the Hong Kong subject. This anxiety has to do with neoliberalization and mainlandization drastically altering Hong Kong reality in uncanny ways.

Stuck with Kung fu and Martial Arts? Hollywood as Proxy of Globalization and the Genre Reification of Hong Kong Cinema

Why are we using neoliberalization rather than globalization as a framework of analysis about the anxiety-provoking conditions of Hong Kong and the Hong Kong film industry? Globalization is an enormous framework to operate. Thus, scholars have often resorted to proxy analytic frameworks such as the study of global–local relations, transnational, diasporic or translocal relations. In Hong Kong cinema studies, this is often done through the proxy framework of local Hong Kong cinema vis-à-vis the global film market dominated by Hollywood.

The automatic suture of global cinema to Hollywood is typical. Cinema “in its very inception,” “was imagined globally” “as a kind of international language,” and “Hollywood looked beyond the nation to a world market” and “an international division of labor” (Kapur and Wagner 2012: 6). Global cinema studies often focus on Hollywood’s clout as the arbitrator of what local cinemas mean globally. Hollywood distribution “cheaply acquired” Hong Kong kung fu / martial arts films and globalized them throughout “the Second and Third World” through B-circuit “cultural dumping” (Willemen 2005; Stern 2010: 196–7). Hollywood quickly incorporates creative elements from other cinemas, denying the original stars and filmmakers brand-recognition in the US, as exemplified by Scorcese’s import substitution: remaking Andrew Lau and Alan Mak’s Infernal Affairs (2002 and 2003) as The Departed (2006), and winning the Academy Award for Best Picture to boot. Even if original directors “remake” their own films “in and for Hollywood,” as the Pang brothers’ Bangkok Dangerous (1999, 2008) (Lim 2011:16, 27), this “ambition to globalize” based on isolated Hollywood successes is still “illusory.” “Undiminished dominance of US distribution” continues to determine market access of foreign films; the US replaces “overseas niche successes with domestic versions”; and escalating blockbuster production cost curtails competition (Walsh 2007: 175).

Ironically, when transnational film studies reverse the Hollywood-Hong Kong hierarchy to show the agency of Hong Kong cinema in localizing creative elements from Hollywood, unconscious Hollywood-centrism still exists in the reversed binary. For example, Heffernan sees a “tradition of working localized variations on Hollywood hits” as the reason for the success of Golden Harvest, taking the horror genre as example. However, he does not recognize that “the white-garbed ghost” (Heffernan 2009: 60–61) is a Chinese staple as much as a Hollywood motif, and that Hong Kong genre cinema draws creative resource not only from Hollywood but also from a long culture of Chinese folk tales and literature on martial arts, romance, and ghost genres that have survived in Hong Kong film and print media while being censored in China and Taiwan during the Cold War.

Transnational genre studies have also shown how the globalization of Hong Kong action genres can exceed the orientalist East–West binary by being transnational. Against the assumption that Hong Kong action cinema can globalize simply because it is non-verbal and thus universally translatable, Jayamanne shows how Jackie Chan failed in Hollywood at first by relying on just that. He succeeded on second trial through building “transnational kinship” ties with minority native American, African-American audiences, crossing “phobic ethnic boundaries,” and making “Black Minstrelsy” and “miscegenation” “cool” (Jayamanne 2005: 155–159). Non-hegemonic East–South transnationalism also exists, like Bulawayo’s transmutation of Hong Kong kung fu cinema to shape their “agitprop” theater and community activism (Stern 2010). Horizontal, intra-Asian intertextuality is also evident. The Hong Kong “wuxia-cum-historical-epic genre” was incorporated into South Korean and Bollywood filmmaking. Stephen Chow’s nonsense kung fu comedy genre got adapted in Japan (Lim 2011: 16–17; Vitali 2010). However, all these examples together cannot but prove that Hong Kong cinema achieves its extraordinary transnational reach as glocalizable (Robertson 1995) commodities only in terms of the kung fu / martial arts genre that Hollywood has chosen to globalize. Triumph is also curse when Hong Kong cinema achieves global visibility through being stigmatized as a kung fu / action cinema by audiences and much film scholarship alike.

Neoliberalization with Colonial Characteristics: Impact on Hong Kong Film

Film studies also tend to take globalization as a context rather than a theory of global capital’s operational logic. We argue that neoliberalism is finally giving globalization studies a theory that can analyze existing global economic assumptions and forms of governance and how they are localized. It also allows us to integrate the analysis of the political economy at large with the analysis of cultural politics in films to show the relation between macro dynamics of the glocalization of neoliberalism and the micro-politics of local cultural responses (Kapur and Wagner 2012: 4). By studying the two scales of analysis relationally, we see how the material condition of cultural production is being adversely shaped by both global neoliberal political economy and specific translocal cultural conditions, and how their impact on the Hong Kong film industry is anxiously articulated in films.

China, Britain, and the US drove the global dominance of neoliberal governance, which led to the “lionization of the free market,” “deregulation” of capital and labor protection, outsourcing, the withdrawal of the state from welfare provisions, the “privatization of social resources,” and “private property” ownership buoyed by credit financing (Smith 2011; Harvey 2005). This has resulted in greater social disparity.

Neoliberalization in Hong Kong went through extra colonial and Chinese turns. Concepts like “Empire” (Hardt and Negri 2000) and “New Imperialism” (Harvey 2003) have tried to associate aspects of colonization and imperialism with globalization and neoliberalism, but fail to explain beyond rhetoric how the transition from “colonization” to “neoliberalization” actually works. We discover in retrospect that colonial Hong Kong actually operated on a logic uncannily similar to neoliberalism after World War II. While most Western democracies moved towards welfare-state policies, Hong Kong’s colonial administration embraced “laissez-faire” as “the principle of non-intervention” in order to produce “acceptable boundaries between public and private interests” within a non-democratic political system based in fact on “the partnership between colonialism and capitalism” (Goodstadt 2005:119, 13). It avoided Western welfare-state interventions and developmental state protectionism (Szeto and Chen 2011: 241; Chen and Pun 2007: 71). Thus, neoliberalization in postcolonial Hong Kong does not have many welfare-state policies to “roll-back.” It simply intensifies the “rolling-forward” of pre-existing neoliberal-like policies. What is new in postcolonial neoliberalization is the “roll-out” (Peck and Tickell 2002) of policies that actively assist in capital accumulation, which Mark Purcell candidly calls “aidez-faire” (Purcell 2008: 15). This refers to pro-market policies such as indirect subsidies to assist capital accumulation. The HK$100 million Film Development Fund, HK$50 million Film Guarantee Fund, and the Film Development Council established to advice the government on spending HK$300 million to revitalize the film industry are some such policies (Chan, Fung and Ng 2010: 26–27).

Accordingly, “[s]o successful was the colonial administration in making laissez-faire … an integral part of the Hong Kong outlook,” no “political party in Hong Kong sought to challenge the legitimacy” of this set of doctrines “in economic management before 1997” or after. The policy is even enshrined in Hong Kong’s Basic Law (Goodstadt 2005: 122, 13). Moreover, the legalization and institutionalization of monopolies and procedural injustices that are trademarks of euphemized colonial governance trickily continues in large measure after 1997, allowing a rather seamless transition from “colonial” to “global” neoliberal exploitation on discursive and practical levels. This allows institutional and business elite more clout to glocalize neoliberalism through existing institutions and discourses. Colonial injustice continues to haunt us as the living dead. Thus, ironically, instead of being recognized as a structural consequence of neoliberalism, the 1997 Asian economic crisis was misrecognized as a cause for intensified market deregulation, state divestment, and fiscal austerity, leading to greater polarization, distress, and anxiety among the citizenry.

Disquieting polarization is also evident in the film industry. The increasing dominance of Hollywood and Chinese film markets is the result of neoliberalization and population size (Kapur and Wagner 2012: 4, 7, 8). Since Deng Xiaoping, neoliberalism became the steering ideology of Chinese market “reform and liberation” (Gaige kaifang) (Harvey 2005). The end of Martial Law in Taiwan was also due to pressures of neoliberalization and democratization. Thus, severe censorship and state controlled market conditions in these Sinophone cinemas protecting Hong Kong from regional competition were eroded. Moreover, film distribution is monopolistic in China. It became the world’s largest film market outside the US in 2013. Its box office is “set to pass the US in seven years” (Pulver 2013). This is a structural policy result of selective market liberalization that threatens smaller local cinemas like Hong Kong.

Moreover, deregulation of the global film market allows increasing mergers and monopolization of film distribution and exhibition that privileges global blockbusters, while withdrawing government protection for small national cinemas. This led to the collapse of art-house cinemas globally, making it difficult for Hong Kong’s type of independent, small filmmaking companies to access mainstream screens, even with much critical acclaim. While other Asian national cinemas with sizeable local populations like Korea, India, and China can rely on the national market to survive, Hong Kong’s small population makes foreign markets a necessity3 (Szeto and Chen 2011: 254–255). But foreign markets are shrinking at fearful speed.

Hong Kong’s combined conditions of residual coloniality and neoliberal governance further intensified the decline of its film industry in the 1990s. Colonial Hong Kong cultural policy prioritized the image of the departing colonial bureaucracy at the expense of local cultural industries. The non-democratic colonial government insisted on laissez-faire / non-intervention policy to protect itself from charges of state-business collusion to the extent that it allowed Hong Kong film, its most important cultural industry, to dwindle unaided in the 1990s, forcing the industry to develop culturally unsustainable strategies of survival that rely increasingly on the Chinese market.4

Mainlandization, the Disquieting Binary Impasse: China or the Rest?

While post-WTO China liberates its markets, censorship and protective measures still apply, due to national interest and security. This “neoliberalism with Chinese characteristics” (Harvey 2005: 120–151; Szeto and Chen 2011) couples tight ideological censorship with selective, controlled market liberalization (Wang 2004). A spectrum of preferential market liberalization measures are extended to the Hong Kong SAR but not to foreign countries under the mainland and Hong Kong Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA) in 2004.5 These privileges coupled with declining local and Asian markets accelerate the restructuring of the Hong Kong film industry towards mainlandization. The seeming rebound of the Hong Kong film industry is often attributed to CEPA policies. But at what cost?

To maximize CEPA privileges through the Hong Kong-China co-production platform, film scripts must pass State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) censorship before shooting. Final cuts must pass censorship again for screening permission. This forces the industry to preemptively self-censor throughout the creative process. The mainlandization of cultural content in Hong Kong–China co-productions refers to this tailoring of cultural content to SARFT parameters on what is acceptable in mainland China6 and not to essentialist assumptions about Chinese tastes. However, mainlandized, deodorized films tend to find “the more liberal Hong Kong and South East Asian markets harder to penetrate,” a producer / distributor for China and Asian markets laments. Conversely, “films made for the Hong Kong and South East Asian markets may contain content excluded” by SARFT (Interview 2, 2010). The Hong Kong ghost genre, popular all over Asia, is censored for promoting superstition; ghost films are rarely made any more.7 So, irrespective of the potential openness and diversity of the Chinese audience, state censorship imposes an artificial cultural divide, forcing the Hong Kong industry to choose between China or the rest.8 The coupling of neoliberalization and mainlandization forces the industry into a disquieting dilemma (Szeto and Chen 2011).

The Hong Kong–China co-production model allows established and above-the-line creative Hong Kong talents and investors to make it big beyond Hong Kong, often faring better in China, calling the shots and setting-up industry conventions. Hong Kong producer John Shum can challenge anyone to name a “big Chinese blockbuster without Hong Kong people in significant roles” (Interview 3, 2010). Dadi Media, which he co-established, owns the fastest-growing cinema chain in China, the sixth-largest in 2012, boasting 1290 screens and aggregating RMB 1 billion in annual box-office (Yisizixun 2013). It succeeds through championing price restructuring: quickly increasing the number of screens in second- and third-tier cities and towns, driving competition to push ticket prices down to RMB$19, nearing 1 percent of local median monthly salary (like mature markets), so that cinema-going quickly turns from a cosmopolitan elite affair to an affordable, widespread quotidian pass-time (Interview 3, 2010; MP Finance 2013). Hong Kong producer / director Peter Chan also opened a production house in Shanghai and soon became the first Hong Kong director to achieve phenomenal Chinese box-office with Warlords (2007), which hinted about state corruption and the suffering multitude, themes that are close to Chinese hearts. Chan’s equivocal remark says it all: Hong Kong films were “made in Hong Kong” in the past but will “definitely be made by Hong Kong” in the future (Interview 1, 2008).

To pacify the anxiety about mainlandization gobbling up the space for Hong Kong cultural identity, cultural critics suggested the “teleportation” (a la Star Trek) of Hong Kong culture to China, in terms of ideas, sensibilities, industry conventions, as a covert form of Hong Kong cultural survival (Lee 2009; Lo 2010; Pun 2012). This idea replaces import substitution with export substitution as a sign of cultural / industrial innovation. Is this not intranational diasporic cultural transmigration, or displaced self-mimicry? Is this not another problematic twist to identity politics of the 1980 to 90s emigrant generation? Moreover, this imagined “Hongkongization” (Szeto 2006) through teleportation of Hong Kong culture comes with a heavy toll: the survival and success of above-the-line, baby-boomer generation talents actually depends on the sacrifice of Hong Kong junior level talents as jobs migrate to China. It is a “winner-take-all” phenomenon.

According to an important SAR New Wave director, young Hong Kong creative talents focused on local stories are confronted with an investment environment increasingly favoring projects targeting China. It takes many compromises to get such films made. The near monopoly of distribution in China makes it difficult for such films to access Chinese screens. Even if they do, without guanxi and bargaining power, they find it difficult to navigate the cumbersome and arbitrary censorship process, avoid bureaucratic quagmires, and overcome red tape. They also have trouble collecting due profit shares from Chinese companies. All these make small and medium Hong Kong productions disproportionately risky financially (Interview 4, 2010). The hurdles of China’s selective market liberalization are stacked against them. Moreover, many below-the-line interviewees lament that Hong Kong crew members need to take pay cuts, accept exploitation, and travel North without per diem to compete, or they have to leave the industry all together, making such careers unsustainable (Interviews 5 and 6, 2009; Szeto and Chen 2013). As a result, the industry sees a severe shortage of younger talents and clear succession problems. This is why the SAR New Wave film Rigor Mortis, while answering the call for succession by a reinvigorating tribute to the Hong Kong hoping zombie / vampire genre banned in China, is at the same time a horrifying statement about the older generation devouring the young and the specters of China crowding out the space of quotidian Hong Kong.

Mainlandization nevertheless, will continue to intensity. As cinema-going becomes more affordable and widespread in China, the taste of the massive Chinese audience becomes more influential. Recently, Chinese films that are grounded in local concerns and sensitivities have become phenomenally successful. Lost in Thailand (Xu Zheng, 2012), a hilarious film about a foreign business trip frustrated by a country bumpkin migrant worker achieved second-highest local box-office (US$197.4 million). Finding Mr. Right (Xue Xiaolu, 2013), a taming-of-the-shrew romance-comedy about the mistress of a Beijing big-shot delivering their illegal child in Seattle grossed US$82.7 million locally. Zhao Wei’s directorial debut So Young (2013), a post-80s college-to-yuppie Bildungsroman grossed US$114.7 million in China. As preferences of Chinese moviegoers, especially the major demography of youthful post-80s and post-90s are continuously shifting towards domestic releases (Cieply 2013),9 mainlandization of Chinese co-production will definitely follow. Peter Chan’s American Dreams in China (2013) for example, plunges directly into the psyche of China’s mainstream, Tian’anmen-generation nouveau riche, their inferiority complex, and money-makes-right vindication vis-à-vis America. With Chinese script and production, this mainland “I Did It My Way” statement won phenomenal box-office and best film, director, and actor at China’s Golden Rooster Awards 2013.

This transition from making quintessential Hong Kong films to complete mainlandization is a complex decision. We have shown elsewhere how Stephen Chow’s career demonstrates the dilemma. He moved from Shaolin Soccer (2001), a proud Hong Kong film refusing to bow to the Chinese market, to successfully globalizing while maintaining local appeal in Kungfu Hustle (2004), and choosing China against the rest in CJ7 (2008), at the expense of halving the profits of Kungfu Hustle (Szeto and Chen 2012). His decision to completely mainlandize in terms of casting and cultural sensitivities in Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons (2013) made it the third-highest-grossing film in China (US$196.7 million), dwarfing the Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Singaporean markets at only 1.8, 1.6, and 0.8 percent of China’s. Chinese market share increased from 0 to 55 percent from Shaolin Soccer to this film. The ontological definition of Hong Kong cinema is called into question by such phenomenal success of Hong Kong–China co-productions.

Younger SAR New Wave and other Hong Kong New Wave / Second Wave directors have obviously experimented with other tactics. We have analyzed the alternative responses of a new slate of anti-heroic comedies elsewhere (Szeto and Chen 2012; Szeto 2014). Here we want to focus on films definitive of the cinema of anxiety as a result of the combined effects of mainlandization and neoliberalization. They include two SAR New Wave films, Rigor Mortis (2013) and Cold War (2012), and the Hong Kong Second Wave film The Grandmaster (2013), all representing different approaches.

Table 4.1 The box office of three films

Source: Figures derived from Box Office Mojo (http://www.boxofficemojo.com) 13 June 2014.

| The Grandmaster (2012) | Cold War (2012)b | Rigor Mortis (2013)c | ||||

| Box Office (US$) |

Share (%) |

Box Office (US$) |

Share (%) |

Box Office (US$) |

Share (%) |

|

| Hong Kong | 2,742,753 | 4.3 | 5,524,043 | 11.1 | 2,211,990 | 62.8 |

| China | 45,270,000 | 71.1 | 40,640,000 | 81.5 | ||

| Taiwana | 1,366,313 | 2.1 | 688,333 | 1.4 | 506,667 | 14.4 |

| Southeast Asia | 1,126,328 | 1.8 | 2,935,193 | 5.9 | 797,049 | 22.6 |

| Japan | 2,330,211 | 3.7 | 0.0 | |||

| Europe | 3,336,556 | 5.2 | 0.0 | |||

| USA | 6,594,959 | 10.4 | 0.0 | 7,865 | 0.2 | |

| Others | 179,988 | 0.3 | 83,594 | 0.2 | ||

| Total | 63,630,256 | 100 | 49,871,163 | 100 | 2,726,522 | 100 |

a Box office data from Taiwan derived from website http://dorama.info 13 June 2014.

b The box office of Cold War in China derived from website http://58921.com/ website 13 June 2014.

c Rigor Mortis was not intended to screen in mainland China, according to the director Juno Mak.

Juno Mak’s Rigor Mortis represents the defiantly localist–globalist approach that bypasses China. It was applauded locally for reinventing a uniquely Hong Kong genre, paying tribute to Mr. Vampire (1985), which launched the hybrid, hopping-vampire / zombie (geongsi), horror-comedy genre. It also received good reviews at festivals worldwide and secured distribution in North America and the rest of Asia. It knows it will do well even if it is banned in China for its “superstitious” genre. It proves how the SAR New Wave can refuse to mainlandize, cut nonsense humor and slapstick, insist on somber social issues, and still thrive by relying on traditional local and regional markets alone: Hong Kong (62.8 percent), Taiwan (14.4 percent), and Southeast Asia (22.6 percent).

Longman Leung and Suny Luk’s Cold War not only did very well in traditional Hong Kong (11.1%) and Southeast Asian (5.9 percent) markets, but also did extremely well in China (81 percent of global market share). The film is supposed to be SARFT censorship fodder. Its theme of systemic failure and corruption in contemporary law and order (in Hong Kong) is a sensitive issue in China. A scene of the hijacking of police officers, the public uproar in the film, and the attempt on the life of the Police Commissioner all beg SARFT censorship wrath. Moreover, there is not one actor or actress from China. The film breaks all assumptions about mainland market viability and makes none of the compromises of co-productions. It found its way into mainland film screens as an import film, which means that it received a lower share of the box office than a Hong Kong–China co-production. However, through help from experienced producers, it achieved the near-impossible: keeping most of its edgy cultural-political implications while garnering a record-breaking US$40.6 million mainland box-office. Its persistent subversion of industry assumptions is itself a near-suicidal act that makes two points: (1) not to give in on sensitive local cultural issues and sensitivities, and (2) to trust the open-mindedness, political sensibilities, and critical awareness of the mainland audience. They appreciate the ability to say critical things in the Chinese context. Mainlandization can look suffocating when dealing with the state, but the inter-local, quotidian, horizontal level of cultural dialogue can be full of pleasant surprises.

Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster competes on a totally different level. It trumps both the national / mainlandization and localist imperatives by claiming the entire world of kung fu / martial arts. The most fascinating part of the film is the making-of documentary-cum-book, which Wong calculatingly uses to conquer Chinese hearts together with Hong Kong and global audiences. The film’s promotion focuses on Wong’s decade long ethnographical pilgrimage to all surviving kung fu masters around the world. The erudite knowledge he accumulated about Chinese martial arts impressed several kung fu masters so much, they wanted to make him a disciple (Wong 2013). He also documented the stars, Tony Leung (from Hong Kong), Zhang Ziyi (China) and Chang Chen (Taiwan) – a Sinophone world trio, practicing real kung fu painstakingly. Chang’s role is cut almost entirely from the film, but his presence as a bajiquan champion of a national Chinese martial arts competition as a result of his dedication to acting his role adds great cultural capital to the hype. The film’s key thesis is to show how Hong Kong, and the Cantonese grandmaster Ip Man, both have the ability to see beyond the essentialist North–South, local–national, Chinese–foreign binary impasses towards the survival of the culture and world of martial arts at large. This is an attempt to show how Hong Kong’s cosmopolitan worldview can claim Hong Kong, China, and all the world at one fell swoop, proven by its US$63.6 million global box-office, with 71 percent from China, while maintaining draw in traditional markets like Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia.

However, all these admirable efforts and positive market signals cannot dispel the anxiety about creative contents of Hong Kong SAR cinema: there is a pervasive urgency to deal with the anxiety-provoking conditions of neoliberalization and mainlandization in the Hong Kong film industry and Hong Kong society at large. This is a long-term predicament that the jubilation of a Hong Kong film revival cannot allay.

Hong Kong SAR New Wave and the Cinema of Anxiety

Take One: Rigor Mortis (2013) – The Theory

The present transformation of Hong Kong film is led by a new generation of filmmakers coming of age in socio-economic and cultural conditions very different from the roaring 1980s. They have to adjust to a prolonged economic downturn after 1997, a neoliberalizing, bifurcated market, and the pressures of mainlandization. We call them the “SAR New Wave” (Hong Kong Film 2010: 84), characterized as the generation of directors who are either (1) new directors coming of age and garnering serious local critical attention after Hong Kong became a Special Administrative Region of China (HKSAR); or (2) directors who joined the industry earlier, but have only gained serious local critical attention and / or acclaim after 1997; but most importantly, (3) directors who are consciously and critically aware of themselves as working from a local condition very different from pre-1997 Hong Kong, who tend to offer more internally varied and inter-locally related portrayals of the local, question vertical, binary identity politics against colonial and national centers (i.e., move beyond the 1997 fixation), and whose worldview departs from the chauvinist petit-grandiose Hong Kongism, a colonial inferiority complex typical of mainstream Hong Kong (Szeto 2006). This SAR New Wave tends to offer the most interesting cultural indicators of change. They arrive on the scene in a Hong Kong that the baby-boomer Hong Kong New Wave / Second Wave no longer know how to handle. Everything looks uncannily familiar, but the rules of the game have changed. Hong Kong literally gets what it wants, status quo, and continued prosperity beyond 1997, but Poverty in the Midst of Affluence (Goodstadt 2013) is a strangely disquieting jouissance to have.

In his seminar on anxiety, Lacan, “clearly sets out where he disagrees with” Freud’s “theory of anxiety … in Inhibitions, Symptoms and Anxiety (Freud 1926).” For Lacan, “the signal of anxiety is not in the ego but ‘in the ideal ego’” (Diatkine 2006), the imaginary. Esther Cheung nails it in the title of her new book on Hong Kong culture, The Uncanny on the Frame (Cheung 2014).

To Lacan, the uncanny, the unheimlich, the objet petit a, appears exactly on the frame, between the imaginary and the real. To Lacan, “the field of anxiety is situated as something framed” strangely. The stage, and by extension, cinema, “allows for the emergence in the world of that which may not be said,” i.e., the objet petit a (Lacan 2014:75), the remainder / reminder of what Hong Kong culture (the Symbolic Order / Other) dumps into its cultural unconscious, refuses to deal with, denies, fails to recognize and symbolize, as if it does not exist.

To Lacan, “the relation between the stage and the world” (Lacan 2014: 75), and by extension, cinema and the world, is the relation between the imaginary and the real. This relation is like the strange phenomenon of the Möbius strip. The remnant of the real, the objet petit a, is like an ant walking on the Möbius strip from one side to the other, from the imaginary to the real, without obstruction, but also without exit. The two sides of the Möbius strip are one and the same. The objet petit a “enters the world of the real, to which, in fact, it is simply returning.” This “specular image” is an “uncanny and invasive image of the double” (Lacan 2014: 97–99), the ghost in the mirror.

Figure 4.1 The vengeful teenage twin ghosts in the mirror in Rigor Mortis (Juno Mak, 2013). Although they are twins, only one is caught in the mirror, but the mirroring forces them out of Chin’s body, exposing their doubleness, their duplicity.

By framing the objet petit a, the spectral in the mirror of reality, art can force it out from hiding, from controlling and taking over the human subject unconsciously. Since the imaginary and the real are the same and the one-and-other side(s) of Möbius reality, framing objet petit a, symbolizing it in the imaginary realm of the film, is also forcing oneself to confront its reality, to confront the murdered / forgotten reality of which it is a persistent reminder / remainder.

The cinema of anxiety is one which dares to take on this objet petit a of anxiety, which is “the appearance, within this framing, of what was already there … at home, Heim,” as an “unknown occupant” (Ibid.). This occupant appears to be disturbingly unexpected and unknown not because it is new, but because it is “that which is Heim,” that which is already at home, but “has never passed through the sieve of recognition. It has stayed unheimlich, not so much inhabituable as in-habiting, not so much in-habitual as in-habituated” (Lacan 2014: 76). It provokes anxiety not because it is unacceptable / inhabituable, but because it is not admitted / in-habituated by our version of reality; not because it is unfamiliar / in-habitual, but because this uncanny / unheimlich object / Other is inhabiting the Heim. Thus, anxiety “isn't about the loss of the object, but its presence.” The objet petit a “causes anxiety not because it might be lost,” like any other common object, as is imagined in nostalgia’s fetishization of the disappearing Hong Kong culture as a “love at last sight” (Abbas 1997: 21), but “because it might have to be shared” (Lacan 2014: 54). That is, the imagined Perverse Other (i.e. the capitalist Other / Order – neoliberalism – mediated by the Chinese national Order / Other – mainlandization, both with demands on us that are excessive, boundless) also demands to enjoy “it.” Thus, anxiety is also about the imaginary competition of jouissance, the competition with the Perverse Other / Order over the imagined object of love, of desire. What is not expected is that “it” turns out to be not the familiar object of love, but the uncanny object petit a.

“Anxiety is the cut,” as a cut could do in film. It “opens up” a gap in the Other / culture and in the self, “affording a view of … the unexpected.” It is the “presentiment, … the pré-sentiment, prior to the first appearance of a feeling.” Thus, anxiety is prior to feelings “whose perception is prepared and structured” (Lacan 2014: 76). In other words, anxiety is an affect (Lacan 2014: 18) not yet processed. “It’s unfastened” to any meaning. It “drifts about. It can be found displaced, maddened, inverted, or metabolized, but it isn’t repressed” (Lacan 2014: 14). “There’s no lack” (Lacan 2014: 54) in anxiety.

The SAR New Wave is a cinema of anxiety, a clinical and forensic science of the real. It tries to catch the objet petit a of Hong Kong culture, which the Hong Kong subject is unaware of. It examines the skeletons in the closet and present their contexts and histories in ethnographic, archaeological, and genealogic detail. It makes earnest effort to see what is there. It consciously takes stock of what is to be salvaged, understood, and transformed. It reckons with cultural landscapes and ways of life literally disappearing unawares, and conserves this culture and way of life for Hong Kong before an undifferentiated vision of Chinese developmentalism, neoliberal city makeovers, and cross-border infrastructural integration with China delete them from our cultural-political consciousness.

Rigor Mortis is a paradigmatic SAR New Wave film of anxiety in the above sense. Hong Kong’s deliberately forgotten real poverty in the midst of affluence is uncannily captured in Rigor Mortis, Latin for “stiffness of death.” The earlier Hong Kong geongsi (Chinese vampire-zombie) horror-comedy genre was popular between the signing of the Sino-British Declaration (1984) and the aftermath of the 1989 Tian’anmen Massacre, around 1992 (Liu 2014), when Hong Kong, a Cold War frontier colonial city, first contemplated the horror of returning to Communist China.

Gone is the self-reassuring humor of that decade. In Rigor Mortis, Chin Siu-ho from the original Mr. Vampire, playing himself, is world weary, down-on-his-luck and past-his-prime, like Hong Kong film and the obsolete geongsi genre, moving back to where he came from, the quintessential Hong Kong public housing estate, to end his miserable life. Quotidian Hong Kong is now a bleak and deserted place, awaiting urban redevelopment, populated by a handful of abandoned souls, the elderly poor, a traumatized waif Feng (Kara Hui), and her lonely albino child, Pak (i.e., Little White). Together they form a microcosm of five generations of Hong Kong poor, echoing sociologist Lui Tai-lok’s popular booklet Four Generations of Hong Kong (2007).

1. Neoliberalism is “dead but dominant”

Capital is dead labor, that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labor, and lives the more, the more labor it sucks.

Karl Marx, Capital, Volume One

Lui’s first generation is born in the 1920s to 1930s, many of whom escaped from war-torn China to Hong Kong. They are Uncle Tung (Richard Ng Yiu-hon) and wife Auntie Mui (Nina Paw Hee-ching) in the film. Auntie, unable to let go of her attachment to her dead husband, goes to extraordinary lengths to bring him back as vampire-zombie, the living dead. To do so, she fed him the only child left in the housing complex, Pak, the millennial generation born after 2000, the fifth generation, unaccounted for in Lui. Notably, the Uncle-Tung-turned vampire-geongsi in the film does not wear traditional Qing dynasty attire like those in the geongsi genre of the 1980s, but the hood of the Western angel of death. It is a hybrid vampire-geongsi, representing glocalized capital: spirits of colonial injustice supposed to be gone in 1997, but in fact still live on within even more malevolently vampiric institutional bodies in Beijing and Hong Kong.

Against Lui’s positive portrayal of the first generation as sacrificial parents, the film uncannily reframes these hard-working laborers behind Hong Kong’s capitalist take-off into their victimizers. This Möbius representational twist puts into our cultural imaginary the disavowed, forgotten cause of problems in the real, gerontocratic, vampiric, neoliberal capital, devouring the only representative of the future, Pak. This vampire-geongsi symbolizes in the imaginary the Perverse Other / Order of capital, whose demands exceeds all boundaries, whose amoral jouissance knows no bounds. The only two remaining third-generation Hong Kong subjects, traumatized Chin and Feng, the parent figures to Pak, are inhibited by anxiety and powerless against this pervasive force.

Neoliberal-capitalism-as-vampire is indeed a disavowed source of Hong Kong’s anxiety. Hong Kong people used to identify with the neoliberal, laissez-faire policy as the formula of their capitalist success. It is Hong Kong commonsense itself. However, since the 1997–8 Asian economic crisis and 2007–08 financial tsunami, it has turned into the unheimlich, horrifying other. In 1998, Hong Kong, the freest city in the world according to neoliberal criteria, did not yet recognize neoliberalism as the cause of the problem. However by 2008, Hong Kong people were shocked into recognizing neoliberalization as a bifurcating, “winner-take-all” phenomenon. When Hong Kong’s rich–poor gap tops all OECD countries despite rising GDP in 2010 (Lau 2010: 20),10 mainly due to the aggregate effects of neoliberal deregulation of the finance and real-estate markets since 1999, even local presses traditionally taking the neoliberal stance acknowledged the need to evaluate the efficacy of neoliberal orthodoxy.

Real estate speculation is the raison d'être of many Hong Kong people. But deregulation of the market and privatization of urban planning have put so much decision-making power into the hands of private developers and semi-public Urban Renewal Authority and Town Planning Board, which collude with relevant government departments, that housing has become unaffordable for the majority of Hong Kong people, younger generations in particular. The increasing number of gated communities and gentrification of old communities are driving out papa–mama stores everywhere. Real estate economy has uncannily become “real-estate hegemony,” a household umbrella term for disparities cause by neoliberal governance.11

In the film, this is the reason for the demise of local shops selling glutinous rice (the talisman Taoist priests use to manage geongsi), which belonged to first generation Hong Kong people. The glutinous rice in the Taoist priest Yau’s (Anthony Chan Yau) hand is the partial object left over from the traumatic real loss of quotidian Hong Kong. He laments:

“In the old days, all successful vampire hunters had special relationships with the best rice shops.” Rice, like their Taoist craft, was “really worth something.” “But since all the vampires have miraculously vanished, along go all vampire hunters.”

First-generation Hong Kong people could rely on hard work and artisanship to make a decent living. However, this is no longer possible in today’s postindustrial, neoliberal Hong Kong.

Yau and his sinister foil Gau (Chung Fat, who dabbles in dark Taoist arts), correspond to Lui’s second generation, the baby-boomers born between 1946 and 1966, who are in control and whose agenda shapes Hong Kong today. They are the Taoist vampire-hunters, the only generation in the film with the managerial technology and experience to keep the Perverse Others (ghosts and geongsi) at bay and under control. These Perverse Orders and others (petits objets a) haunting the housing estate (home, Heim) include the Uncle-Tung-turned vampire-geongsi (by implication, vampiric capital), the towering procession of ghosts in traditional Chinese attire (by implication the enormous mainland China factor), and the vengeful teenage-twin ghosts (the forgotten fourth generation Hong Kong victims wronged by the baby-boomer father-figure). The baby-boomers are however, also the generation that created the ghosts and geongsi in the first place. They are the most obscenely consumerist and neoliberalist generation that exploited all resources of the past and future generations, and the generation most in denial of their role in the horror, both inside and outside the film.

In the film, Feng’s husband, a baby-boomer, raped the teenage twins he was privately tutoring at home. This is the ultimate act of exploitation and betrayal that produced the twin ghosts. Gau is the one who unscrupulously strangled Uncle Tung to satisfy his desire for geongsi-making experimentation and who taught Auntie Mui how to turn her husband’s body into a geongsi. To trap the twin ghosts, Gau is willing to let them take over Chin’s body and soul. The cigarettes Gau smokes to prolong his life are made from the ashes of the unborn.

Against these horrific fathers / Others, Chin and Feng, parent figures to Pak, could do nothing to save their child and themselves. They belong to Lui’s third generation, born between 1967 and 1975. They are the powerless, anxious generation, whose only strategy is suicidal terrorism, to perish with the enemy (Lacan’s passage à l'acte).

The vengeful ghosts of the twins are les objets petit a, the reminders / remainders of the real unrecognized anger of the fourth generation (born in the 1980s and 1990s, called the post-80s and post-90s in local parlance). Indeed, the legitimacy of the post-80s’ and post-90s’ anger is what the baby-boomer generation is in denial of. This anger is also the objet petit a of Lui, who is a baby-boomer. He symptomatically portrays the fourth generation as middle-class youths living in material abundance and overprotected by baby-boomer parents. He is in complete denial of the less fortunate and more critically aware among the third and fourth generations. But the younger generations are rightfully angry with the reality baby-boomers have left them. Are not Occupy Wall Street, Tarhir Square, and recent massive youth activism in Hong Kong real reminders enough?

The only person left alive in the film is the baby-boomer Taoist priest, Yau. He is able to manage having dinner and watching TV with the mild ghosts of yore at home. But even his managerial technology is no longer sophisticated enough to deal with the mutant monsters of their generation’s own making: the vengeful spirits of the youthful twins merging with the body of the gerontocratic vampire.

However, the younger generations, like the post-80s director Juno Mak (himself the son of a famous local tycoon and financial market maverick), have intimate knowledge of the problem. Their generation is able to realize that although the global economic meltdown lingering in Europe exposed the “failure of neoliberalism on its own economic terms,” many of the policies and institutions it created are still “powerfully in place,” like the living dead. Neoliberalism is “dead but dominant” (Smith 2011). Its imposed structural adjustments continue to be suffered by “the 99 percent” globally. Increasingly, the younger generations in Hong Kong are perceiving this as a result of structural colonial injustice ruthlessly institutionalized in the name of global neoliberalization driven by the post-1997 government–business growth-coalition in Beijing and Hong Kong (Goodstadt 2005: 223, 226–228, 2013: 1–56; Mingpao 2010).

2. Mainlandization as Spectral “Neocolonial” presence

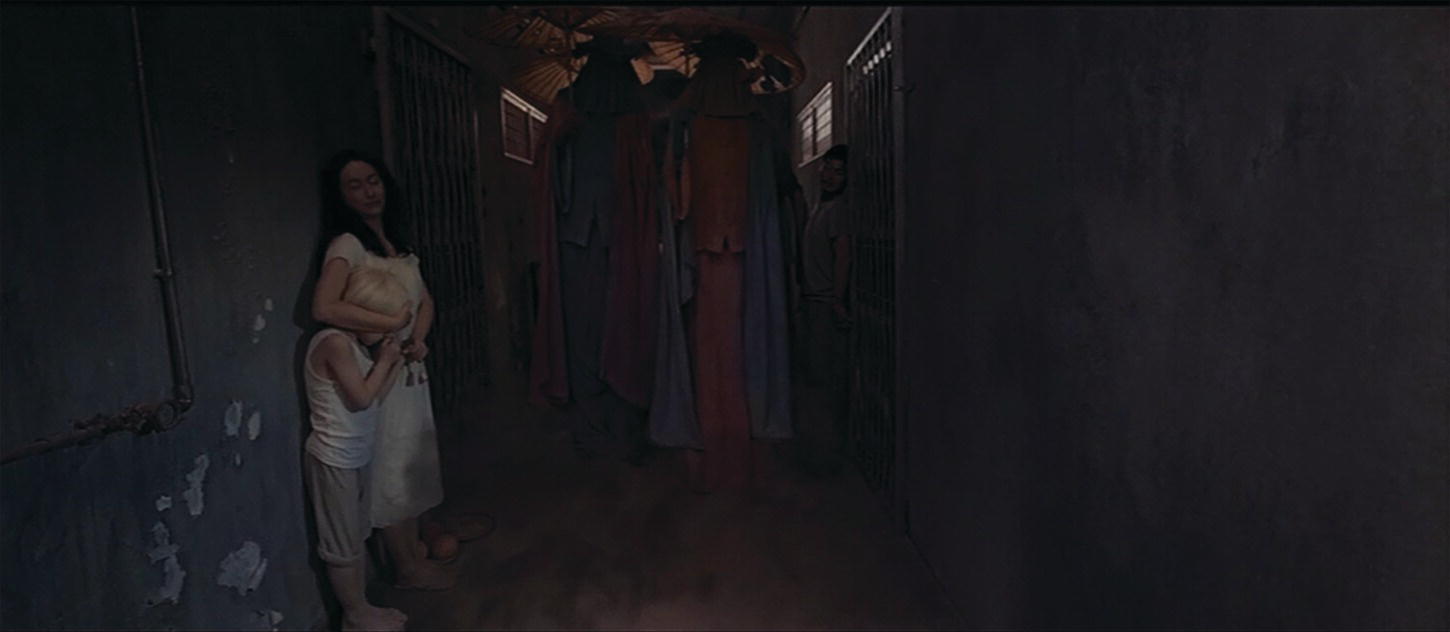

Consequently, mainlandization takes on more sinister “neocolonial” meanings in mainstream Hong Kong culture. In the film, the entire living space of local people is haunted / colonized by a towering spectral procession in traditional Chinese attire, a force much grander in scale than humans and locals. Feng and Pak are reduced to beggars at their mercy, feeding on the offerings people made to them. China is framed as these giant specters.

Figure 4.2 Spectral Chinese forces towering over Hong Kong people, colonizing, haunting their entire living space in Rigor Mortis (Juno Mak, 2013).

Indeed, gradual integration with and competition from Chinese cities and increasing inter-local interaction in daily life and social media has heightened Hong Kong people’s awareness about the inter-local nature of injustice, exploitation, and political repression. Politically, the Beijing–Hong Kong ruling elite continued to obstruct democratization in Hong Kong and China. The disparity between dissenting activists, journalists, intellectuals, and artists against China’s monumental stability-maintenance system is perceived as increasingly suffocating. Economically, due to the asymmetrical scale between the colossal Chinese consuming / investing public and the Hong Kong free market, Hong Kong, once a proud shoppers’ paradise, finds itself overwhelmed by mainlanders competing for real estate properties, safe health care, clean food, and places in its liberal education system. In 2013, Hong Kong received a record-high 54.3 million visitors, 75 percent of whom were from China (Tourism Commission 2013), constituting more than five times the local population. Tiny Hong Kong is overwhelmed by the neoliberal deregulation of tourism. Coupled with gradual immigration from China, intensified transborder relations are now perceived as a disturbing erosion of Hong Kong’s core values and ways of life. China is seen less as a developmentalist blessing than a threat of mainlandization, understood in a xenophobic manner as the infiltration of negatively perceived mainland cultural habits: the increase in corruption and decrease in consumer and citizen rights, the invasion of global brand-name chain-stores serving mainland tourists pricing out quotidian eateries and affordable papa and mama shops.

3. Fighting Neoliberal Gerontocracy and Mainlandization: Getting Real?

Amidst this duress, Hong Kong cultural politics have taken a decisive turn, especially in the hands of post-1980s and post-1990s youth. Their defense against high-handed neoliberal and national transformation of the local is to collectively take stock of what really matters and affirm with each other their commitment to a shared future, like Arab youths and post-World War II third and fourth generations elsewhere. Hong Kong recorded increasing numbers of protests and demonstrations, 7,529 incidents in 2012 alone (Lin 2013), with much about defending what is imagined as Hong Kong culture, way of life and core values. Hong Kong is now a city of protests.

Recent social movements demonstrate public distancing from the Beijing–Hong Kong ruling elite’s vision of Hong Kong–China integration, which is negatively perceived as a form of mainlandization. In 2012, over 120 thousand people joined the anti-national education demonstration led by the post-90s high-school student group Scholarism. This is the largest local student movement since the 1960s, and strikingly, is overwhelmingly supported by parents, teachers, and the public. It succeeded in revoking the national education curriculum reform, perceived by most Hong Kong people as Beijing’s attempt to indoctrinate Hong Kong kids in party-line worldviews.

What is happening to Hong Kong is far from what Shu-mei Shih characterized as the “large-scale, state-sponsored migration and settlement” of the dominant Chinese into “Tibet, Xinjiang … through a process of continental colonialism that takes the form of settler-cum-internal colonialism” (Shih 2013: 4). However, whether xenophobia against China can be prevented while breathing space can still be had for Hong Kong culture and politics, and how the asymmetrical China and Hong Kong markets can be juggled are real problems that Hong Kong must confront. It can no longer afford to navigate daily life without some vertical reference to mainlandization.

Take Two: Cold War (2012) – Generational Warfare and Quotidian Hong Kong–China Identification

If Rigor Mortis is the grassroots, get-real perspective directed by a rich guy, then Cold War is the middle-class wishful-thinking perspective directed by grassroots directors. While the younger generations all got killed by the elders in the former, they win the generational “Cold War” in the latter.

The multiple winner at HKFA 2013, Cold War is the directorial debut of SAR New Wave directors Longman Leung and Sunny Luk.12 It dramatizes succession power struggle and anxieties about the neoliberalization and mainlandization of Hong Kong core values. “Cold War” in the film is the code for a police operation to rescue hostages of a hijack in which an armed police van carrying advanced equipment and highly skilled officers has disappeared. The hijackers have intimate knowledge of police procedures and are steps ahead of the game. The police must comply with a list of demands to ensure hostage release. With the Police Commissioner stepping down soon, rivals for the post, young Deputy Commissioner (Management) Sean Lau (Aaron Kwok) and old fox Deputy Commissioner (Operations) Waise Lee (Tony Leung Ka-fai) fight to take charge of the operation. Whoever succeeds gets the top job.

Lau wants to negotiate with the hijackers while covertly tracking them down, and has elite support from the Secretary for Security (Andy Lau). He represents the Rule of Law, professionalism, due procedure, sophisticated research and technology, elitism; core values of the Hong Kong middle class, refined and brainy wen masculinity. Lee, on the contrary, represents the older generation’s Rule by Personal Command, placing force of character, charisma, personal loyalty ahead of morality and the law. He wants to win by hook or by crook and believes in streetwise combat logic, ends justifying means. He perpetrates a system of practices open to abuse of power and corruption. He rose through the ranks, has the support of rank and file officers, and represents a more grassroots, jianghu wu (martial arts) masculinity. Hong Kong and China audiences would find him a semblance of mainland Chinese officials. Thus, he embodies the worry about mainlandization of local governance: the intensification of systemic corruption and decay in post-1997 Hong Kong.

Beneath regular cop motifs is an unusual political recognition about the threat of mainlandization and neoliberalization on the Hong Kong way of life. The gist of the film is its reference to the worsening reality in Hong Kong. Together with Johnnie To’s Life Without Principle (2011), Cold War portrays Hong Kong’s political-economy affected by extended neoliberal deregulation. As a result, one of the last vestiges of Hong Kong pride, its clean and transparent business environment and governance that people hold onto as Hong Kong’s defining core value, has been eroded from within and irreparably tainted. There is no transnational crime cartel to crack, nor the usual shoot-outs and special effects. The focus is on the mind-game, the gradual and uncanny revelation about the internal, structural decay and systemic injustice within the police force itself. The mastermind behind the hijack is an ex-police officer, resentful of being unjustly fired, taking revenge on his bosses and the corrupt system.

This echoes not only usual news from China but also the actual re-emergence of institutional and corporate elite corruption, bribery, graft, unbridled misconduct and excesses in Hong Kong. In 2013, the ex-commissioner of the Hong Kong Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) is himself being investigated by the ICAC. He spent public money extravagantly on gifts and feasting for mainland Chinese officials and was appointed after retirement as a delegate to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Committee. Allegations over graft, collusion with corrupt Chinese officialdom, and compromise of the Hong Kong intelligence and anti-corruption system shook the confidence of the Hong Kong public to the core. Did he get his mainland appointment due to his willingness to provide intelligence on Hong Kong people to the draconian Chinese security maintenance system? Did he compromise investigation of corruption in Hong Kong involving mainland VIPs? The ex-Chief Executive Donald Tsang, his second ranking man Rafael Hui, the billionaire Kwok brothers, and a slate of officials appointed by the new Chief Executive are all under investigation for graft and bribery.

Crowning the younger, upright Lau, the representative of the rule of law, as the succeeding Commissioner, winning over the baby-boomer Lee’s dubious practices, the film implies the need for Hong Kong law and order to be passed onto worthy hands. The wishful ending in which Lee puts his own son into the hands of the law for the abuse of systemic failures speaks to the psychological need of the Hong Kong citizenry to reaffirm clean governance and the rule of law as Hong Kong core values. Through casting, the son of Commissioner Lee is a figure alluding to the sophisticated, well groomed but nonetheless corrupt and abusive princelings now ruling over China. Having such a figure being busted by Lau, a home grown talent with high moral integrity, comforts audience anxiety about the worst type of mainlandization: the Hong Kong governing and business environment operating more and more like the corrupt conditions of China. Interestingly, the mainland audience also identifies strongly with the issues portrayed and celebrates the film’s lucky escape from the clutches of censorship.

Take Three: Conclusion by way of The Grandmaster (2013) – Succession Planning, Letting Go and Winning Back the World

We end with a film that poses questions back to ways in which the two SAR New Wave films imagine Hong Kong anxieties. It is a contemplation on the anxiety of Hong Kong cinema by a director whose long silence exemplifies it. As a part of this cinema of anxiety, this film emerges out of the tunnel by letting go some of the anxious symptoms.

Wong Kar-wai is a master among the Hong Kong New Wave / Second Wave, a group who belong to the baby-boomer generation, coming of age during Hong Kong’s transition to Chinese sovereignty. They made their marks while riding the economic high tide of the 1980s and 90s and continue to dominate Hong Kong Film Awards (HKFA)13 during the economic low tide. Despite individual efforts to nurture young talents, as a cohort, they find it difficult to let go of their baby-boomer narcissism, give way to younger talents, gracefully step back and be the judging panel. The gerontocratic vampire metaphor is not without validity in this patriarchal industry. The real turning point was HKFA 2011, when SAR New Wave directors Derek Kwok and Clement Cheng won best film with Gallants (2010). The trend seems to be confirmed when Cold War (2012), Longman Leung and Sunny Luk’s directorial debut garnered best film, director, screenplay, film score, and visual effects at the HKFA 2013. But then Wong Kar-wai returned to devour twelve wins in HKFA 2014, despite the ironic fact that The Grandmaster (2013) is a rare baby-boomer statement that foregrounds the urgency of succession planning.

The Grandmaster is about the solemn responsibility of a whole generation of kung fu masters, and implicitly film masters, to pass on the tradition. The film represents kung fu as a national tradition that has survived a century of historical traumas through taking root in Hong Kong and the global Chinese diaspora. The “youngest” among existing kung fu masters Wong interviewed for the film are like most Hong Kong New Wave / Second Wave filmmakers. They have survived the Communist era and are now in their fifties and sixties, anxiously planning succession.

One thesis of The Grandmaster is the three stages of realization when mastering an art, whether martial arts or film-making, and by implication life. The first stage merely “sees oneself” (見自己) (Wong K.W. 2013: 45). One is obsessed with one’s skills, achievements, status. Such works regress to a narcissistic, nostalgic, exclusivist, essentialist obsession with itself. Such films are defensive and limiting.

The second stage “sees heaven and earth” (見天地) (ibid.), and by implication, the conditions of the world. This is when art confronts survival against brutal reality and stark material conditions. This alludes to Hong Kong filmmakers concerned about survival vis-à-vis the global and China markets. Such filmmakers might succeed financially, but might not be able to transcend and break through paradigms in ways worthy of the grandmaster title. Such works are important for the survival of kung fu or film, but they might not survive the ultimate test of time.

The third and final stage “sees humanity / the multitude / bare life” (見眾生). Only through the compassionate, expansive, humbling recognition of humanity can one truly bring a culture, an art, a community through the trials and trepidations of modern and contemporary history, and pass it on across time and space, with dignity and grounded equanimity. Such is the responsibility of a grandmaster of martial arts or of film, like Ip Man (master of Wing Chun, a Cantonese native of Foshan) and Wong Kar-wai. Wong’s film is inspired by the fact that Ip, three days before his death, asked his son to film him doing his martial arts. The moment of vulnerable pause in Ip’s demonstration tells of a master trying “to return all one has learned from life to humanity” unto his last breath (Wong K.W. 2013: 45, 41). Ultimately, the recognition of mastery is not in the totalizing command of the world and the universalizing incorporation of heaven and earth, but in the humble realization of finitude in life, culture, and art.

The second thesis of the film concerns older grandmaster Gong of the Northern tradition saying, “if the old never let go, when will the young get their chance?” The young Ip Man of the Southern tradition won over him and become the next grandmaster not due to invincible skill, but due to his ability to see beyond the narrow essentialist North–South binary impasse towards the survival of the culture and world of martial arts at large. Ip was able to take the traumatized kung fu community into the future through persistence in compassionate and dignified teaching, despite adversities. Indeed, the heights of Chinese kung fu and Chinese film were achieved amidst the turmoil of colonialisms, wars, and revolutions.

The third thesis is embedded in Wong’s foregrounding of his decade-long quest for global knowledge about kung fu (Wong K.W. 2013). Our earlier reading about calculative promotional strategies does not preclude another level of cultural politics. Wong, like Ip Man, also humbly recognizes the finitude of a film or kung fu master against the inexhaustible and expansive history and culture of martial arts. The global talking point of this film is Wong’s inability to produce a satisfying final cut, and how much significant footage he left out in every version. In the anxious, procrastinatory process of preparing and making this film, Wong has come to reconcile with the fact that one can never present the world a full picture of a culture. He lets go of making a much longer directorial cut, as any length cannot totalize a culture and an art. He has come to realize the vastness and fragility of the global Sinophone worlds of film and kung fu, against which he sees the place of Hong Kong.

The way to overcome the anxiety of competition and cultural survival among Hong Kong, Chinese, and other Sinophone cinemas is, Wong demonstrates, not to limit one’s cultural access and entitlement to any categories, be it the local, national, diasporic, transnational or hybrid, but to recognize the fact that one is entitled to what one makes an earnest effort to learn; to recognize the fact that through painstaking devotion to the art and craft of filmmaking, one can in fact give voice to a whole generation of global Sinophone kung fu history, without forgetting the humility of film’s finitude. One will never be able to exhaust and totalize a culture. What one can master is merely courage and daring to pose the challenge of a cultural and cinematic statement so definitive that other filmmakers find it hard to transcend.

But do SAR New Wave filmmakers just starting out have the resources and conditions to play the game like Wong the grandmaster? Yet Wong seems to imply through portraying Ip Man in his youth that all mastery need to prove its worth by starting from scratch, and by persistently overcoming difficult transitions in the best and worst of times; that all one can take charge of is the verve to invent a paradigm, carve out a niche, blast into a field, and venture out into the open as unprotected bare life. And by implication, Hong Kong film and culture must see beyond the impasses of colonial, national binarisms, go beyond the imagination of mere survival in the gaps of coloniality and global givens, and overcome the fatalism and self-denigration of inferiority complexes and defensive chauvinisms, to see the self and others just as they are.

All in all, the three films demonstrate how the post 1997 Hong Kong SAR Cinema of Anxiety is about anxiety, but not necessarily stuck with anxiety. It is exactly by staging, framing, and cutting into the real of anxiety that it is able to turn around and move on.

References

- Abbas, Ackbar (1997), Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Apple Daily (2013), “Miliye wanlang, Chen Guo xinpian wubeishang”《迷離夜》玩狼,陳果新片唔北上 (Tales from the Dark Part 1 makes fun of C.Y. Leung: “Fruit Chan's New Film doesn't go North”), Apple Daily 蘋果日報 (26 June).

- Box Office Mojo, http://boxofficemojo.com. Accessed Accessed January 20, 2015.

- Brody, Richard (2013), “When Night Falls and Django Unchained: Movie Censorship in China,” The New Yorker (24 May).

- Chan, Joseph M., Anthony Y.H. Fung and Chun Hung Ng (2010), Policies for the Sustainable Development of the Hong Kong Film Industry, Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- Chan, Ho-sun Peter (2008), speech at Rayson Huang Theatre (22 October), University of Hong Kong.

- Chan, Ho-sun Peter (2011), speech at “Meeting Film-maker Peter Chan: Public Forum on Wu Xia” (30 September), Rayson Huang Theatre, University of Hong Kong.

- Chen, Yun-chung, and Ngai Pun (2007), “Neoliberalization and Privatization in Hong Kong after the 1997 Financial Crisis,” China Review 7.2: 65–92.

- Cheung, Esther M.K. (2014), Xiezai chuangkuang de guihua 寫在窗框的詭話 (The Uncanny on the Frame), Hong Kong: Infolink Publishing Ltd.

- Cheung, Esther M.K. and Stephen Chu Yiu-wai (ed.) (2004), Between Home and World: A Reader in Hong Kong Cinema, Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

- Cheung, Kit-ping 張潔平 (2013), “Zhuanfang Hanzhan daoyan/bianju Liang Lemin, Lu Jianqing” 專訪《寒戰》導演/編劇梁樂民、陸劍青 (“Interview with directors of Cold War, Leung Lok-man and Luk Kim Ching”), City Magazine 號外 439 (April): 66–71.

- Chu, Stephen Yiu-wai (2013), Lost in Transition: Hong Kong Culture in the Age of China, Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- Cieply, Michael (2013), “U.S. Box Office Heroes Proving Mortal in China,” New York Times (22 April), http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/22/business/media/hollywoods-box-office-heroes-proving-mortal-in-china.html. Accessed January 20, 2015.

- Curtin, Michael (2007), Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience: The Globalization of Chinese Film and TV, Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Daily Telegraph (2012), “China Eases Foreign Film Quota,” Daily Telegraph (20 February), http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/film-news/9093686/China-eases-foreign-film-quota.html. Accessed January 20, 2015.

- Diatkine, Gilbert (2006), “A Review of Lacan’s Seminar on Anxiety,” International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 87:1049–1058.

- Freud, Sigmund (1990), Inhibitions, Symptoms and Anxiety, Volume 20, Standard Edition, Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Norton.

- Goodstadt, Leo (2005), Uneasy Partners: The Conflict Between Public Interest and Private Profit in Hong Kong, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Goodstadt, Leo (2013), Poverty in the Midst of Affluence: How Hong Kong Mismanaged its Prosperity, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri (2000), Empire, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Harvey, David (2003) The New Imperialism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Harvey, David (2005), A Brief History of Neoliberalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Heffernan, Kevin (2009), “Inner Senses and the Changing Face of Hong Kong Horror Cinema,” in Horror to the Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema (eds. Jinhee Choi and Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano), Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 57–68.

- Hong Kong Film 香港電影 (August 2010), Issue 33.

- Interview 1, by Mirana Szeto and Yun-chung Chen, 22 October 2008, Hong Kong, with Peter Chan Ho-sun, prominent Hong Kong director-producer who has moved headquarters to China.

- Interview 2, by Mirana Szeto and Yun-chung Chen, 3 June 2010, Hong Kong. This informant from Southeast Asia is a pan-Asian producer for Asian filmmakers with medium to smaller budgets films for local, regional, and global markets.

- Interview 3, by Mirana Szeto and Yun-chung Chen, 26 May 2010, with John Shum Kin-fun. He has been in the Hong Kong film industry for over 3 decades, is an industry leader in production, exhibition, distribution, and union organizing. He is co-founder and senior executive of Dadi Media corporation based in both China and Hong Kong.

- Interview 4, by Yun-chung Chen, 28 September 2010. This informant is an important Hong Kong SAR New Wave director who has joined the industry for fifteen years, who wants to remain anonymous for speaking up about sensitive issues.

- Interview 5, by Mirana Szeto and Yun-chung Chen, 26 August 2009. This informant is a production assistant who joined the film industry in 2000.

- Interview 6, by Mirana Szeto and Yun-chung Chen, 29 October 2009. This informant is a self-employed, sub-contracting recording artist who has joined the industry in 2001.

- Jayamanne, Laleen (2005), “Let’s Miscegenate: Jackie Chan and His African-American Connection,” in Hong Kong Connections: Transnational Imagination in Action Cinema (eds. Meaghan Morris, Li Siu-leung and Stephen Chan Ching-kiu), Durham, NC: Duke University Press; Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 151–162.

- Kapur, Jyotsna and Keith Wagner (2012), “Introduction: Neoliberalism and Global Cinema: Subjectivities, Publics, and New Forms of Resistance,” in Neoliberalism and Global Cinema: Capital, Culture, and Marxist Critique (eds. Jyotsna Kapur and Keith Wagner), London: Routledge, 1–16.

- Lacan, Jacques (2014), Anxiety: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book X (trans. A.R. Rice), Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Lau, Siu-kai (2010), “Threat of Riots is Exaggerated,” The Standard (Hong Kong) (12 April): 20.

- Lee Chiu-hing, Bono (Li Zhaoxing 李照興) (2009a), “Chaobao zhongguo: xianggang zaixian zhi gangshi chachanting shuoqi – Xianggang teleportation zhiyi,” 潮爆中國:香港再現之港式茶餐廳說起–香港 teleportation之一 (“Chic China Chic: Re-presentation of Hong Kong through Hongkongese teahouse and beyond – Hong Kong teleportation I”), Mingpao (23 August).

- Lee Chiu-hing, Bono (Li Zhaoxing 李照興) (2009b), “Chaobao zhongguo: hougangchanpian de biyu Xianggang – Xianggang teleportation zhier,” 潮爆中國:後港產片的比喻香港 teleportation之二 (“Chic China Chic: the allegory of post-Hong Kong films – Hong Kong teleportation II”), Mingpao (30 August)

- Lee, Vivian P.Y. (2011), “The Hong Kong New Wave: A Critical Reappraisal,” in The Chinese Cinema Book (eds. Song Hwee Lim and Julian Ward), Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lim, Song Hwee (2011), “Transnational Trajectories in Contemporary East Asian Cinemas,” in Vivian P.Y. Lee (ed.), East Asian Cinemas: Regional Flows and Global Transformations, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 15–32.

- Lin Kai-wen 林凱旻 (2013), “Youxing weihe nameduo” 遊行為何那麼多?(“Why so many demonstrations in Hong Kong?”), Hong Kong: Mingpao 明報 (24 March), A1.

- Liu, Yee Man Mandy (2014), “Re-interpreting Hong Kong's Horror Comedy of “Geong-si” (Jiangshi movies) in Post-colonial Context” (in Chinese), M.Phil. dissertation, Hong Kong: Lingnan University.

- Lo Yin-shan (2010), “Yinyong qijie geming: you shiyue dao yiyue weicheng,” 引用騎劫革命:由十月到一月圍城 (“Quoting/hijacking revolution: from October to January City Blockade”), Haitanhuangsha de boke 海灘黃沙的博客 (Haitanhuangsha’s Blog) (15 January), http://834439758.blog.163.com/blog/static/1367699872010015114641698/. Accessed 12 June 2013.

- Lui, Tai Lok (2007), Sidai Xianggangren 四代香港人 (Four generations of Hong Kong), Hong Kong: Stepforward.

- Mingpao Editorial (2010), “Alarm Bells are Ringing,” Hong Kong: Mingpao, English Page (12 April), D9.

- Mingpao (2011), “Qichengliuren zhi pinfuxuanshu yanzhong,” 七成六人指貧富懸殊嚴重 (“76 percent of Hong Kong people think that the disparity between rich and poor is severe”), Mingpao (2 December). http://news.mingpao.com/20111202/goh4.htm. Accessed 2 December 2011.

- MP Finance (2013), “Yingyuan exingjingzheng piaojiadizhi shijiuyuan,” 影院惡性競爭 票價低至19元 (“Cinemas’ vicious competition, fares as low as 19 RMB”), MP Finance (27 May), http://www.mpfinance.com/htm/finance/20130527/News/eb_eba3.htm Accessed 27 May 2013.

- Peck, Jamie and Adam Tickell (2002), “Neoliberalizing Space,” Antipode 34(3): 380–404. Reprinted in Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe (eds. Neil Brenner and Nik Theodore), Oxford: Blackwell, 33–57.

- Poon, Alice (2005), Land and the Ruling Class in Hong Kong, Richmond, BC: A. Poon. Chinese translation, Poon Wai-han 潘慧嫻 (2010), Dichan baquan 地產霸權 (Real-Estate Hegemony), Hong Kong: Tianchuang chuban.

- Pulver, Andrew (2013), “China Confirmed as World’s Largest Film Market Outside US,” The Guardian (22 March), http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2013/mar/22/china-largest-film-market-outside-us. Accessed January 20, 2015.

- Pun, Kwok-ling Lawrence (2012), “Xianggang wenhua de neidi zaixian,” 香港文化的內地「再現」(The mainland-re-presentation of Hong Kong culture), Mingpao Monthly, 2012(10): 2.

- Purcell, Mark (2008), Recapturing Democracy: Neoliberalization and the Struggle for Alternative Urban Futures, London: Routledge.

- Robertson, Roland (1995), “Glocalization: Time-Space and Homogeneity–Heterogeneity,” in Global Modernities (eds. Mike Featherstone, Scott Lash and Roland Robertson), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 25–44.

- Shih, Shu-mei, Chien-hsin Tsai, and Brian Bernards (eds.) (2013), Sinophone Studies: A Critical Reader, New York: Columbia University Press.

- Smith, Neil (2011), “Neoliberalism: Dominant but Dead,” first presented as “Cities After Neoliberalism?” (27 June), http://www.academia.edu/6424629/Cities_After_Neoliberalism. Accessed January 20, 2015.

- Stern, Lesley, (2010), “How Movies Move (Between Hong Kong and Bulawayo, Between Screen and Stage…),” in World Cinemas, Transnational Perspectives (eds. Nataša Ïurovièová and Kathleen Newman), London: Routledge, 186–216.

- Szeto, Mirana M. (2006), “Identity Politics and Its Discontents: Contesting Cultural Imaginaries in Contemporary Hong Kong,” Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, 8(2), 253–275.

- Szeto, Mirana M. (2014), “Sinophone Libidinal Economy in the Age of Neoliberalization and Mainlandization: Masculinities in Hong Kong SAR New Wave Cinema,” Sinophone Cinemas (eds. Audrey Yue and Olivia Khoo), Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 120–146.

- Szeto Mirana M. and Yun-chung Chen (2011), “Mainlandization and Neoliberalism with Postcolonial and Chinese Characteristics: Challenges for the Hong Kong Film Industry,” Neoliberalism and Global Cinema: Capital, Culture, and Marxist Critique (eds. Jyotsna Kapur and Keith Wagner), London: Routledge, 239–260.

- Szeto Mirana M. and Yun-chung Chen (2012), “Mainlandization or Sinophone translocality? Challenges for Hong Kong SAR New Wave Cinema,” Journal of Chinese Cinemas, 6.2: 115–134.

- Szeto Mirana M. and Yun-chung Chen (2013), “To Work or Not To Work: The Dilemma of Hong Kong Film Labor in the Age of Mainlandization,” Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, 55, Fall, http://www.ejumpcut.org/trialsite/SzetoChenHongKong/index.html. Accessed January 20, 2015.

- Time Out (2013) “Interview: Juno Mak,” (5 October), http://www.timeout.com.hk/film/features/61523/interview-juno-mak.html . Accessed January 20, 2015.

- Tourism Commission (2013), “Tourism Performance in 2013,” Hong Kong Tourism Commission, http://www.tourism.gov.hk/english/statistics/statistics_perform.html. Accessed January 20, 2015.

- Vitali, Valentina (2010), “Hong Kong-Hollywood-Bombay: On the Function of ‘Martial Art’ in the Hindi Action Cinema,” in World Cinemas, Transnational Perspectives (eds. Nataša Ïurovièová and Kathleen Newman), London: Routledge, 125–150.

- Walsh, Mike (2007), “Hong Kong Goes International: The Case of Golden Harvest,” in Hong Kong Film, Hollywood and the New Global Cinema: No Film is an Island (eds. Gina Marchetti and Tan See Kam), London: Routledge, 167–176.

- Wang, Hui (2004), “The Year 1989 and the Historical Roots of Neoliberalism in China,” in positions: east asia cultures critique (trans. Rebecca E. Karl), 12.1: 7–70.

- Willemen, Paul (2005), “Action Cinema, Labor Power and the Video Market,” Hong Kong Connections: Transnational Imagination in Action Cinema (eds. Meaghan Morris, Li Siu-leung and Stephen Chan Ching-kiu), Durham, NC: Duke University Press; Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Wong, Kar-wai 王家衛 and Jet Tone Film Production (2013), Yidai zongshi 一代宗師 (The Grandmaster), Taipei: Thinkkingdom Media Group Ltd.

- Yisizixun 藝恩諮詢 (2013), “2012 nian yuanxian suliang chuangxingao dadi yuanxian piaofang zengsu diyi” 2012 年院線數量創新高 大地院線票房增速第一 (2012 record increase in number of cinemas, dadi box-office expansion fastest) (14 March), http://www.entgroup.cn/views/a/16090.shtml. Accessed May 1,2013.