18

A Pan-Asian Cinema of Allusion

Going Home and Dumplings1

Bliss Cua Lim

The notion of “pan-Asian cinema” crystallized in the aftermath of the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the downturn experienced by the film industries of Hong Kong, China, Taiwan, and Japan (Davis and Yeh 2008: 85–86; Teo 2008: 343–344). Its inception thus coincides with a broader tendency towards “market-led” regionalization in Northeast and Southeast Asia, which saw an increasingly “integrative market for culture,” even as the project of forging a unified “Asian” identity faltered (Otmazgin 2013). It should be noted, though, that this contemporary variant of pan-Asianism – strongly rooted in economic integration and the flow of commodities – is distinct from earlier culturalist notions of Asianism articulated from the late nineteenth century to the first half of the twentieth century by figures like Tenshin Okakura, Rabindranath Tagore, and Sun Yat-sen as an ideological bulwark against Western encroachment (Ge 2000; Korhonen 2008).

According to Darrell Davis and Emilie Yueh-Yu Yeh, the term “pan-Asian cinema” encompasses a range of film-related practices: “talent-sharing, cross-border investment, co-productions (which may be unofficial, or backed by formal treaties), and market consolidation, through distribution and investment in foreign infrastructure” (Davis and Yeh 2008: 85). A model of “economic cooperation and co-production” between film producers in neighboring Asian countries, pan-Asian filmmaking has been dubbed a “survival strategy” (Teo 2008: 345), one that hopes to consolidate the currently fragmented Asian film market into a vast regional audience. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that film producers in neighboring Asian countries, who once conceived of each other as rivals, have in recent decades embraced “co-operation and regional consolidation” (Davis and Yeh 2008: 85, 91, 93; Teo 2008: 351). What Nissim Otmazgin refers to as “regional media alliances” (2013: 36) took the form of co-financing and co-production between Asian film industries. As Caroline Hau and Takashi Shiraishi point out, co-financing was nearly negligible in the 1980s and 1990s, when “less than three per cent of films were co-financed” in the Hong Kong film industry. In contrast, “co-financing exploded in the years 2004–6, when 38, 55, and 51 per cent of films were co-financed” (2013: 83). In the same period, the roster of Hong Kong cinema’s financial partners expanded to include investors from not only mainland China, Taiwan, and Japan, but also the US, South Korea, Macau, Thailand, and Singapore.

Seen from a globalist lens, pan-Asian tactics attempt to push back at Hollywood dominance. This bears out Leo Ching’s argument that “regional discourse does not operate independently: it is always directed against another territorial discourse” (2000: 239). Global Hollywood casts a long shadow over pan-Asian cinema. In interviews, pan-Asian filmmaker Peter Ho-sun Chan has voiced his dream of consolidating the currently fragmented Asian film market into a vast regional audience: excluding China, Chan estimates that the combined total population of key Asian markets approaches 300 million (Jin 2002). 300 million estimated consumers is the very figure that anchors the Hollywood film industry’s huge domestic market, even as a globalized Hollywood becomes increasingly dependent on overseas revenue (Davis and Yeh 2008: 92–93).

Seen from a regionalist lens, on the other hand, pan-Asian film production tries to find “a new way to put Asia together as a market” (Davis and Yeh 2008: 91) and yearns to cultivate the enormous and potentially lucrative audience base of mainland China (Teo 2008: 345; Curtin 2010: 119). A quintessentially regionalist cinema (Hau and Shiraishi 2013: 78–81), Hong Kong, with its historical reliance on Southeast Asian markets and its long history of regional co-productions dating to the 1950s, was well-placed to strongly articulate a vision of pan-Asian media production in response to the decline of its domestic market and demand from Southeast Asia and Taiwan since the 1990s (Lim 2006: 349–351). The first commercial realization of the pan-Asian model in the Hong Kong film industry was Applause Pictures, co-founded in 2000 by a team of industry players: Peter Chan, Teddy Chen, and Allan Fung. The pan-Asian cinema initiative launched by Applause Pictures drew on financiers, directors, actors, production, and post-production personnel with ties to Singapore, Korea, mainland China, Thailand, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Japan (Davis and Yeh 2008: 94–95).

A Pan-Asian Cinema of Allusion?

The two films considered in this paper, Going Home (Peter Chan, 2002) and Dumplings (Fruit Chan, 2004), originated as episodes in the anthology franchise Three (2002) and Three…Extremes (2004). Early examples of Applause Pictures’ pan-Asian model, these two films are rarities in the emerging corpus of pan-Asian cinema. Whereas most pan-Asian films deracinate, deliberately minimizing cultural and historical specificity in order to maximize broad market appeal, Going Home and Dumplings foreground cultural and historical embeddedness through their allusions. This essay grapples with that tension between deracination on the one hand and cultural and historical specificity on the other in these two allusive pan-Asian films.

For Stephen Teo, pan-Asian cinema’s intentional erasure of cultural nationalisms in the service of historical forgetting are exemplified by two Hong Kong-Chinese co-productions, The Promise (Chen Kaige, 2005) and Perhaps Love (Peter Chan, 2005) (Teo 2008: 354–355). Eschewing the “effacement of cultural nationalism” (Teo 2008: 354–355) that Teo incisively identifies as a hallmark of pan-Asian filmmaking, Going Home and Dumplings conspicuously foreground culturally and historically embedded allusions to traditional Chinese medicine (zhongyi), Maoist and post-socialist Chinese history, and bilingualism (Cantonese and Mandarin, or putonghua) in narratives overtly concerned with the blended lives of mainland physicians who travel between mainland China to the north and Hong Kong to the south, denizens of a porous border zone (Yeh and Ng 2009: 150).2 In a nutshell, I suggest that the antinomy between these pan-Asian films’ attempt to inclusively address a broad audience through tactics of deracination on the one hand, and the potential exclusion of viewers unfamiliar with its cultural and historical references, on the other, are contradictions internal to the workings of a nascent pan-Asian cinema of allusion exemplified by Going Home and Dumplings.

In an essay conceptualizing allusion as an “expressive device” deployed by the New Hollywood cinema of the 1970s and 1980s, Noël Carroll defined allusion as

an umbrella term covering a mixed lot of practices including quotations, the memorialization of past genres, the reworking of past genres, homages, and the recreation of ‘classic’ scenes, shots, plot motifs, lines of dialogue, themes, gestures, and so forth from film history, especially as that history was crystallized and codified in the sixties and early seventies

(Carroll 1982: 42).

As distinguished from New Hollywood allusionism, allusion in pan-Asian filmmaking expands its intertextual purview beyond the formalist, film-historical, auteurist references listed by Carroll, evoking wider-ranging cultural and historical associations that are recontextualized, reversed, or otherwise transformed. In Going Home and Dumplings, allusions also carry affective power: both films are infused with conflicted nostalgia from the perspective of post-handover Hong Kong or post-socialist China. In particular, Dumplings – by thematizing sex, cannibalism, and abortion – serves up a startling affective mix of horror, shock, dark humor, and raunchiness.

Allusionism typically includes some audiences while excluding others; this is the elitism of indirect reference. The ideological project of pan-Asian cinema, however, retools allusion. The incipient pan-Asian cinema of allusion pioneered by Hong Kong’s Applause Pictures is bifurcated in its mode of address: first, in an inclusive gesture, films like Dumplings and Going Home attempt to consolidate regional viewership and speak to translocal audiences through their play with genre. Yet, both films offer a second, more exclusive layer of perceptual pleasures to select “insider” audiences in possession of relevant cultural competencies and reading protocols.

The two films’ foregrounding of traditional Chinese medicine is fascinating in this regard, since it combines both inclusive and exclusive forms of audience address: on the one hand, traditional Chinese medicine commands a certain translocal legibility among regional audiences in East and Southeast Asia, even as its specific circumstances in Communist China may be unfamiliar.3 Traditional Chinese medicine shops abound in Southeast Asian countries like Singapore, Thailand, and the Philippines (People’s Daily 2000a , 2000b), and aspects of traditional Chinese medicine have been integrated into the medical traditions of Korea, Japan (kampo) (Yu, Takahashi, Moriya et al. 2006:231–239) and Indonesia (jamu; the majority of jamu manufacturers in Indonesia were historically Peranakan Chinese). An iconic example of the regionalization of Chinese medicine is Tiger Balm, a popular menthol- and camphor-based therapeutic ointment whose initial marketing campaign is described by Sherman Cochran as an early twentieth-example of “pan-Asian transnationalism and transculturalism” (2006:122).

In contrast to the regional familiarity of certain forms of Chinese medicine, the specific histories of Maoism and market socialism, which form a dense connotative web in Going Home and Dumplings, are likely to be decrypted only by those knowledgeable about its contexts in mainland China and Hong Kong. So traditional Chinese medicine, as addressed to Asian regional audiences, is both legible and foreign, familiar and unfamiliar: the uncanny of pan-Asian allusionism. In these films, the “spectacularization” of traditional Chinese medicine in the visual track (lingering lateral tracking shots of herbs being chopped and decocted in Going Home) or on the audial track (pointed conversations about traditional remedies in Dumplings) may function simultaneously as an opaquely foreign, exotic motif for audiences unfamiliar with traditional Chinese medicine, while simultaneously being read as “authenticating” intertextual gestures by cultural insiders.

In contrast to the deracinative quality of most pan-Asian filmmaking, Going Home and Dumplings are so culturally specific that key elements – traditional Chinese medicine, Maoist and post-Maoist Chinese history, and Cantonese/Mandarin bilingualism – are likely to be at least partially opaque or illegible to audiences who are not cultural insiders. That perceptual difficulty is acknowledged in an interview with prominent pan-Asian director–producer Peter Chan. Chan’s interviewer remarks that Going Home’s focus on traditional Chinese medicine renders the story inaccessible and implausible to Western audiences:

the approach of Chinese medicine in Going Home is really different from the Western one… We couldn’t make this story possible in Western countries because people would not really accept what this doctor is doing to his wife. Did you take that into consideration when you did Going Home, this approach of Chinese medicine?

(Francois and Sonatine 2003).

In response, Peter Chan downplays the tendency of such references to fence out certain viewers. For Chan, zhongyi (traditional Chinese medicine) is merely “a way of telling a story… I was hoping the audience would just believe in the story that I’m telling not because of Chinese medicine, but because of love.” Chan explains that he was hoping to entice audiences with a hybrid genre film that opens as a horror film, mutates into a psychopathic thriller, and ends as a melodrama (Francois and Sonatine 2003). Chan downplays the differential degrees of legibility or unfamiliarity that Going Home might elicit among different regional viewers, hoping instead that the foreignness of zhongyi to some audiences might be mediated by the global legibility of genre films.

Going Home and Dumplings, two accomplished pan-Asian films, experiment with an incipient pan-Asian cinema of allusion. Both films aspire to an appropriate balance between regional and global legibility (achieved through genre) and cultural embeddedness (allusions to traditional Chinese medicine, Maoist and post-Maoist history, and the asymmetrical relationship between Mandarin and Cantonese). In what follows, I unpack the contours of that gamble.

Going Home and Zhongyi Histories

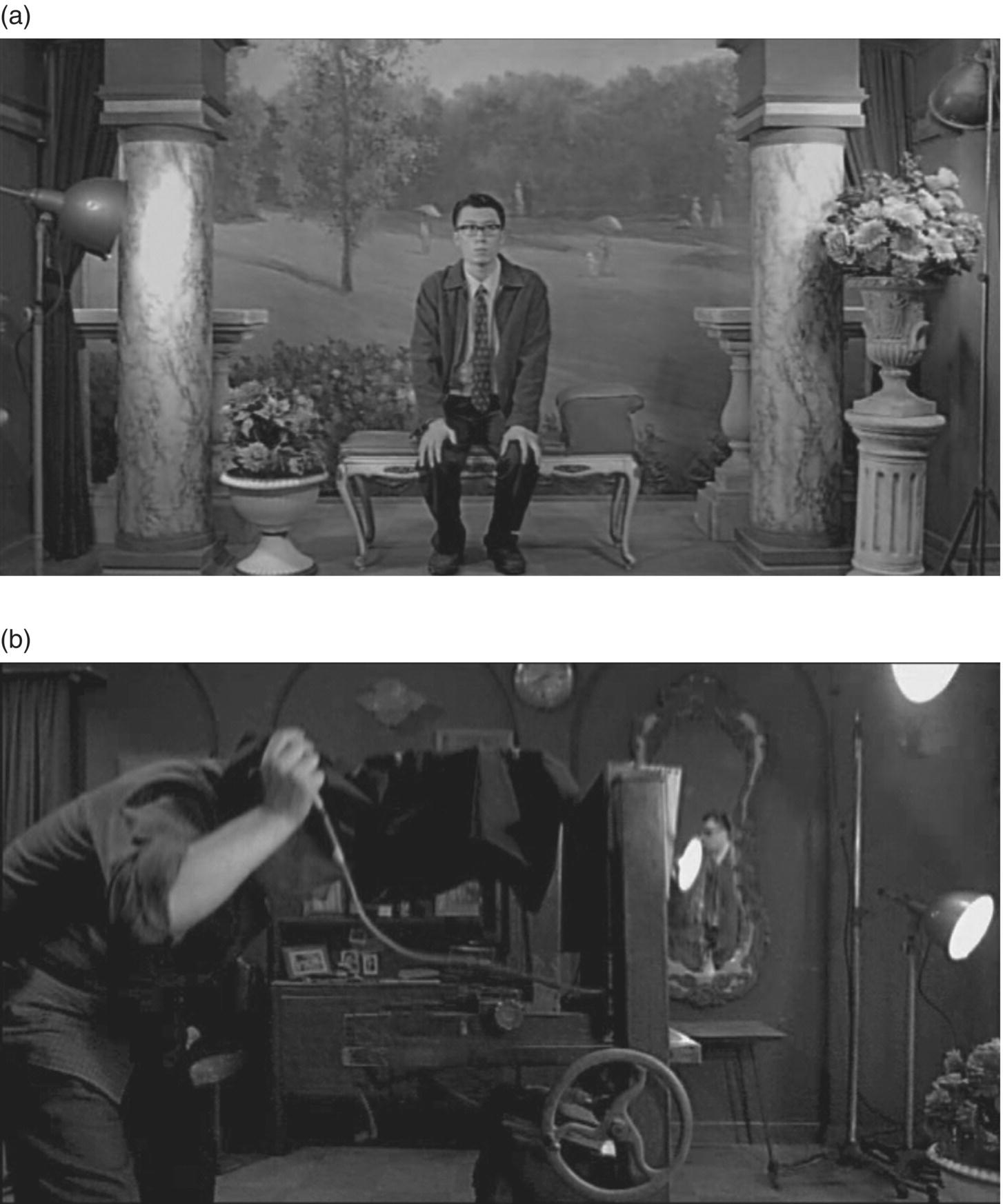

Going Home opens with a prologue in antiquated photographer’s studio from the 1950s or 1960s. An anonymous man poses for a studio portrait in a kitschy interior mise-en-scène whose columns, balustrade, drapery, fake foliage, and painted backdrop (see Figures 18.1a and b) recall the studio conventions of long-exposure photography in the Victorian era (Benjamin 1977: 46–51). Linking spectrality to image technologies, the prologue establishes several of the film’s most important motifs. At key moments in the film, being dead is likened to becoming an image: the ghostly presence of a three-year-old girl dressed in red is signaled by graffiti on the apartment building where most of the action unfolds. Throughout the film, the co-presence of the dead with the living comes through in images: in graffiti, photographs, VHS tapes, and mirrors. The newly dead, we learn by the end of the film, come to the photographer’s studio to have their portraits taken before moving on. That the ghost-girl initially declines to pose for a photograph foreshadows the refusal of both living and deceased characters in Going Home to accept the verdict of death.

Figure 18.1 In Going Home (Peter Chan, 2002), the newly dead come to the photographer's studio to have their portraits taken before moving on.

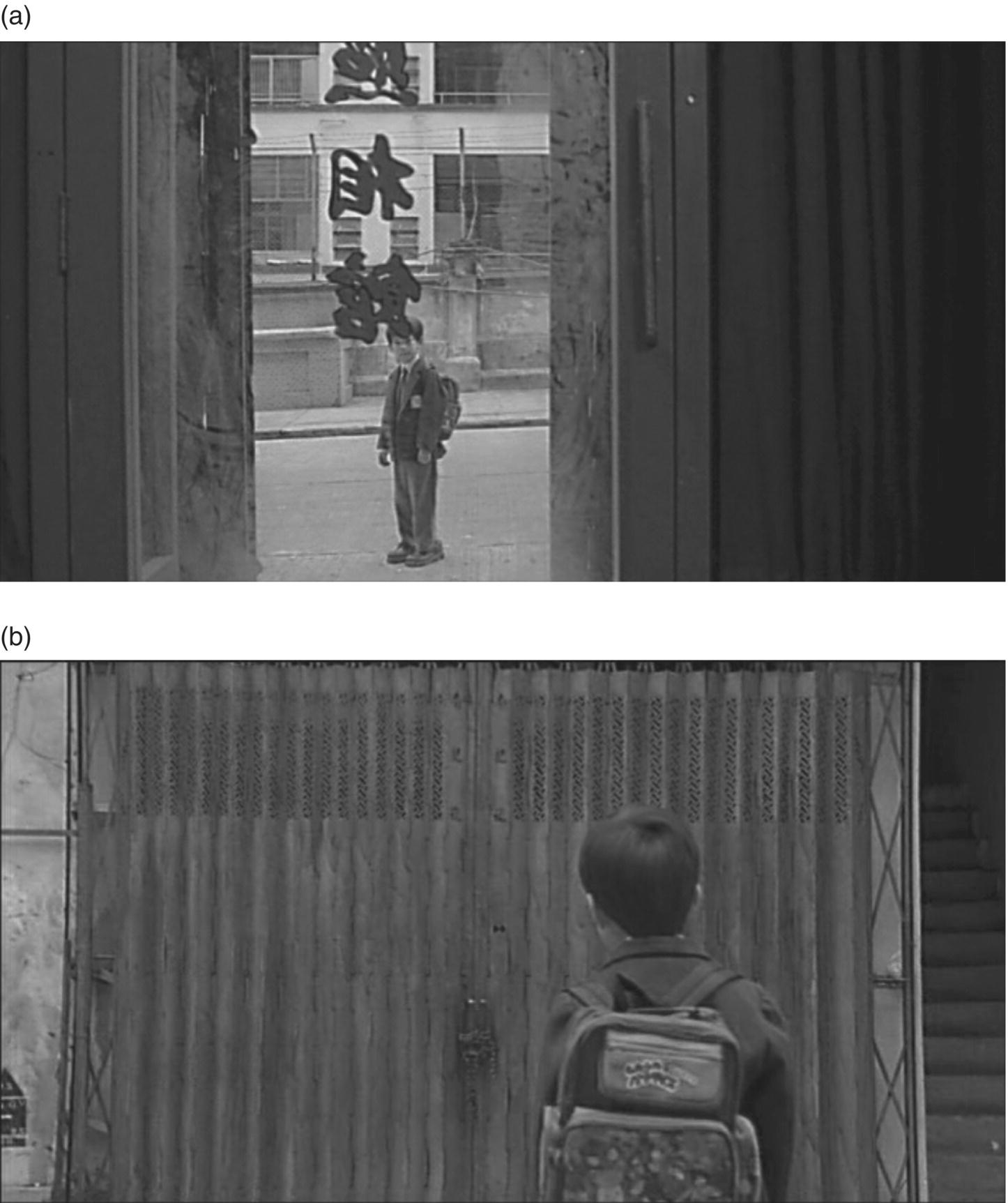

The prominence of mirrored and glass surfaces highlights a preoccupation with opacity, transparency, and reflectivity on the film’s image track. Going Home plays with conventions of continuity editing to suggest that the glass door of the studio is only selectively transparent. In a recurring pattern of alternating shot/reverse shot taken from either end of the axis of action, a shot from within the photographer’s studio looks out through the glass onto a bright street scene outside. It is then followed by an exterior reverse shot looking into the same photographer’s studio, our vision obstructed by a locked steel door (see Figures 18.2a and b). In such exterior reverse shots, the once-transparent window has become a one-way mirror, allowing those on the inside to look out, while obstructing the view from the outside in. The old-fashioned photographer’s studio is death’s waiting room, its door marking the threshold between life and death. The dead can see into the world of the living, but the living are, for the most part, blind to the dead.

Figure 18.2 The glass door of the photographer's studio is transparent when seen from the interior. However, our view of the same door is obstructed when viewed from the exterior.

Going Home introduces a world inhabited by socially marginal figures in present-day Hong Kong. Newcomers to a low-income neighborhood, a divorced policeman, Wai (Eric Tsang) and his young son, Cheung (Li Ting-fung) move into a dilapidated apartment complex that most of the residents have abandoned. Interestingly, Going Home was shot on location in “old police quarters in [Hong Kong’s] Western District” (Cheung 2009: 93). The little boy Cheung and his father meet their neighbor, Yu (Leon Lai), who is said to be caring for his paralytic wife, Hai’er (Eugenia Yuan). Shots of Yu preparing herbs and roots or dragging heavy garbage bags oozing a brown sludge to the garbage dumpster establish Yu as a doctor of traditional Chinese medicine, framing that occupation in decidedly sinister terms. Such devalorization of zhongyi physicians at the beginning of Going Home is, strictly speaking, unrealistic: as Judith Farquhar has pointed out, traditional Chinese medicine is currently very popular in China’s market economy (2002: 27). We see Yu alone with his wife, who sits eerily still and silent in the bathtub while he chatters excitedly about their trip back to mainland China in four days’ time to celebrate Chinese New Year. Since the only shots of Hai’er moving or speaking are conveyed through her reflection in a mirror, we begin to suspect that Yu’s wife is dead and that he is hallucinating her responses; death is again linked to particular types of visuality (see Figure 18.3).

Costuming contributes another layer of uncanniness to character exposition. Assuming that the mainland characters’ ages are approximately those of the actors playing them, Yu and his wife Hai’er are in their mid to late thirties during the story’s temporal setting in the early 2000s. They belong to a generation that older mainlanders disparage as the “spoiled children of the [market] reform era,” who grew up during China’s shift towards a capitalist market economy in the 1980s. The mainland couple’s drab, desexualized clothing, however, is strikingly anachronistic, reminiscent of the “unisex trousers and jackets of the Maoist era,” that gave way to “markedly gendered clothing” in the late eighties (see Figure 18.4; Farquhar 2002: 15–16). The Maoist inflection of the mainland couple’s anachronistic appearance in 2002 evokes the asceticism and collectivism of the pre-1980s Maoist ethos instead of the conspicuous consumerism of today’s oxymoronic “socialist market economy.”

Figure 18.3 The only shots of Hai’er (Eugenia Yuan) speaking are of her reflections in mirrors or her recorded image on videotape.

Figure 18.4 The mainland zhongyi doctors’ anachronistic costume is reminiscent of the desexualized clothing of the Maoist era.

After the spectral little girl lures the policeman’s son to the photographer’s studio, the cop mistakenly suspects his neighbor of having kidnapped his son. Policeman Wai breaks into his neighbor Yu’s apartment and discovers the latter’s morbid secret. For the last three years, the zhongyi physician has been caring for the immaculate corpse of his beautiful wife, bathing her daily in herbal remedies. Yu overpowers the policeman in his apartment and holds him captive. Revealing that he and Hai’er were both zhongyi physicians, Yu promises to free Wai in three days’ time, when his wife revives. A heated altercation between policeman Wai and the zhongyi doctor Yu follows, which explicitly compares traditional Chinese medicine to “Western” biomedicine: When Wai points out, “Your wife is dead!,” Yu replies, “Western science would agree with you. But her tumors can be driven out. If I immerse her in Chinese herbs every day, she’ll revive when she’s well.” “Tumors? Revive?” asks Wai, incredulous. “You’ve strangled her.” “I strangled her to cure her,” the doctor of Chinese medicine retorts, struggling to maintain his composure. At this point in the film, the zhongyi practitioner appears as an impoverished, outmoded, homicidal madman. Traditional Chinese medicine here contrasts unfavorably with biomedicine (Bates 2006: 37), as pointed up through Yu’s exchange with the skeptical policeman.

What we now call “traditional Chinese medicine” is a complex, reified myth produced out of a protracted encounter with “Western” biomedicine (Zhan 2009:12; Lei 2002: 357–358). Healing practices indigenous to China, formerly referred to simply as medicine (yi), became ethnicized and temporalized as traditional Chinese medicine (zhongyi) only after China’s charged encounter with science in the second half of the nineteenth century. Chinese medicine was denigrated by the modernizing, reform-minded Chinese intellectuals of the May Fourth period’s New Culture Movement (1917–1927), who championed biomedicine as necessary to modern China. It was from the perspective of a reactive championing of biomedicine as new or Western medicine (xinyi or xiyi, respectively) that the therapeutic know-how present in China prior to the early twentieth century was reframed as a type of medicine that was quintessentially Chinese (zhongyi), anachronistic (jiuyi, old medicine), and national (guoyi, national medicine) (Zhang 2007: 19–20).4

During the era of the nationalist republic in China (1912–1949), Sun Yat-sen’s Guomindang (Kuomintang: KMT) actively strove to abolish the old medicine. In 1914, the government banned zhongyi, calling it a vestige of the feudal Confucian culture that modern China must leave behind. The establishment of the Communist-ruled People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 inaugurated a drastic change in official attitudes towards zhongyi, now relegitimized in ideological terms as nationalist, mass-based, anticolonial, antifeudal, and anti-elitist. A period of institution-building for zhongyi practitioners followed in the 1950s, a decade that closed with Mao’s famous comparison of zhongyi to “a great treasure house” for China (Zhang 2007: 20).

In both Going Home and Dumplings, then, the persistent association between traditional Chinese medicine and the Maoist era alludes to this conflicted history and to the Communist regime’s historical support of zhongyi (Zhang 2007: 18–20, 22). The anachronistic costuming of the zhongyi physicians in Going Home alludes to vexed questions of temporality invoked by both critics and adherents of zhongyi, simultaneously prized as a reservoir of tradition and derided as an anachronistic obstacle to modernization (Zhang 2007: 152). The point here is that, in contrast to the effacement of cultural nationalism that typifies pan-Asian cinema, the emphasis on zhongyi in Going Home foregrounds competing varieties of cultural nationalism, not just between Hong Kong and the mainland, but within mainland Chinese history itself, as in the conflicting visions of China articulated by both the KMT and the Communist party.

On the long-awaited day of Hai’er’s revival, the temporal pressure is acute. The police have discovered that both Wai and his son Cheung are missing; Yu, their only neighbor, is under suspicion. Realizing that Hai’er is about to revive, Yu frees Wai, apologizing for imprisoning him while they awaited Hai’er’s return to life. Too late: the police raid Yu’s apartment and arrest him, just as his long-dead wife blinks for the first time.

The wordless montage that follows, heightened to an emotional pitch by a plaintive violin leitmotif adapted from the opening bars of Georges Bizet’s “Je crois entendre encore” (“I still believe I hear [your voice]”), is strongly ironic. Hai’er comes back to life just as her husband is arrested. Sitting handcuffed in the police car, Yu watches incredulously as his wife, alive at long last, is taken for dead and carried out in a metal coffin. Yu escapes, chasing after the vehicle that is taking Hai’er to the morgue. While standing in the street, he is run down by a car and killed.

In the wake of Yu’s death, three highly expository scenes chart the cop’s dawning understanding of the couple’s painful ordeal. In the first of these scenes, a forensic pathologist tells the cop that although Hai’er has been dead for a few years, her strange (zhiguai) body remains lifelike, with no sign of decay. The next scene shows Wai listening to a biomedical doctor recount his treatment of the couple during Hai’er’s pregnancy three years earlier. The physician reveals that the pregnant Hai’er had been diagnosed with liver cancer and forced to abort their child. Ironically, Hai’er’s husband had also been diagnosed with liver cancer three years prior to Hai’er’s illness, but claimed that “Chinese medicine had cured him.”

The pronouncements of the forensic pathologist and the couple’s biomedical physician uphold the magical efficacy of zhongyi and solicit our sympathy for the strange mainland couple, who are belatedly humanized in our eyes by their ordeal. In contrast to the sympathetic zhongyi doctors, the forensic pathologist and the biomedical physician whom Wai interviews are faceless, filmed in long shot or from behind the shoulder. The detached, rational objectivity of Western medicine ultimately proves less efficacious than the obsessive, necromantic love of the zhongyi practitioners. The denouement not only attests to the necromantic couple’s extraordinary faithfulness in love but also vindicates their faith in traditional Chinese medicine.

Zhongyi’s capacity to “defy a death sentence” through a clinical miracle is crucial in establishing its legitimacy against the authority of biomedicine. Mei Zhan explains that clinical miracles, particularly those involving late-stage cancers, operate in an explicitly comparative frame, demonstrating zhongyi’s incredible ability to treat diseases that biomedical therapies had pronounced incurable (Zhan 2009: 93–94). By vindicating Yu’s seemingly superstitious therapeutic practices, Going Home admonishes the skeptical cop (a surrogate for the skeptical audience) that zhongyi works. Despite its legitimizing function, however, the clinical miracle by definition signifies marginality, further positioning zhongyi as a fringe practice in relation to biomedicine and science (Zhan 2009: 101).

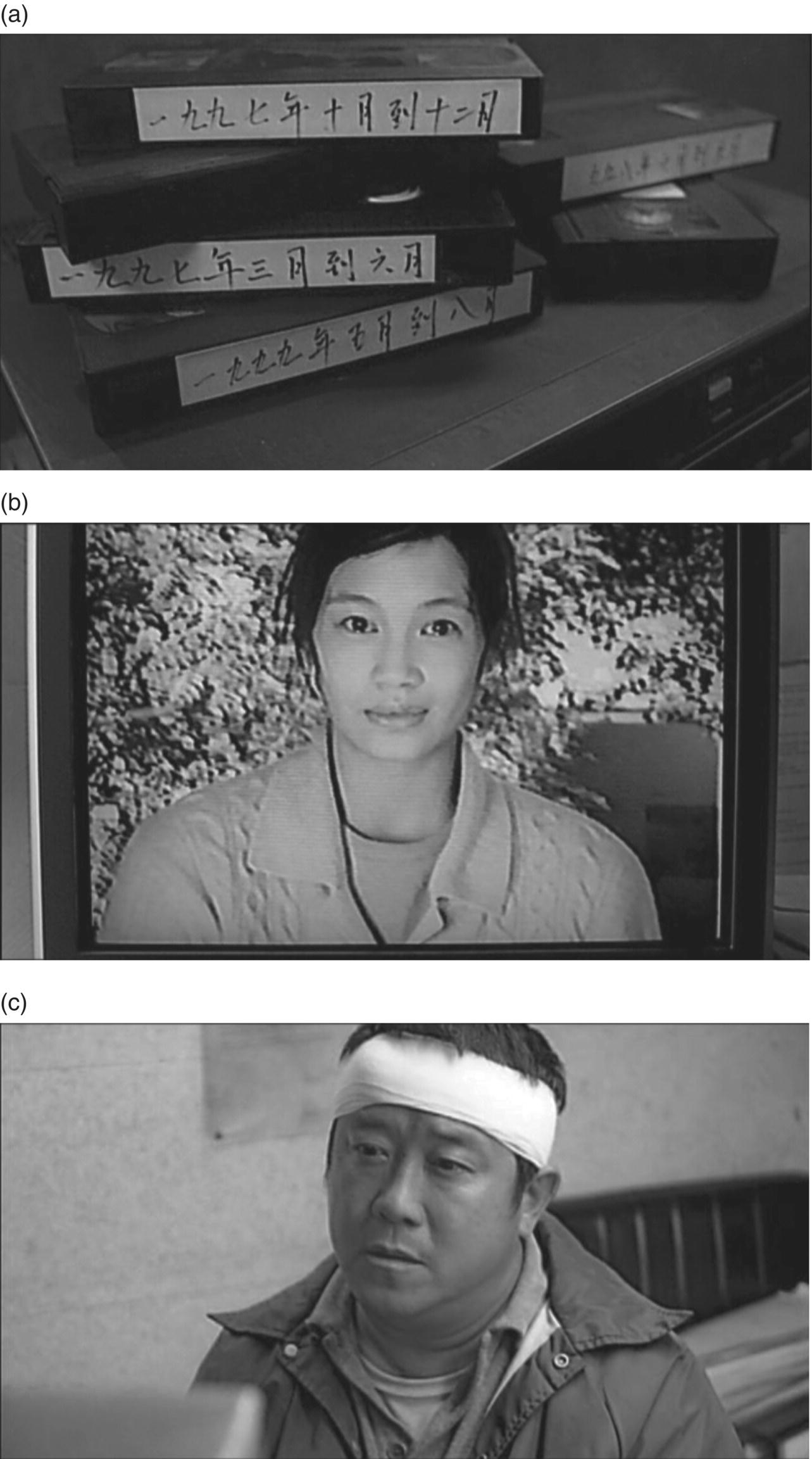

The film’s final scene completes the cop’s (and the spectators’) retrospective understanding of what has happened. The videotapes piled by Yu’s TV set are labeled with dates ranging from 1997 to 1999, placing Yu’s death and resurrection within the temporal range of the handover of Hong Kong to China. The cop watches Hai’er’s final video letter to her husband, captured on VHS tape shortly before she died (see Figure 18.5a, b, c). Recorded over a used tape of her ministering to Yu over the preceding three years, Hai’er’s tape has been replayed hundreds of times as Yu turned to it for reassurance. Watching it, we realize that Hai’er tended to her dead husband’s corpse in the same way years before, bathing his body in medicinal herbs until he was resurrected. The video quality is poor and grainy because, unlike digital recording formats, the image quality of analog video degrades with use and re-recording. As Lucas Hilderbrand points out, the degeneration of videotape over time and use indexes the tape’s generationality and bears the durative imprint of its circulation (2009: 7). The distortion and degradation of Yu and Hai’er’s well-worn VHS tapes – over-dubbed, watched too much, and loved too well – attest indexically to the couple’s repetitive sharing and devoted re-screening of their own excruciating tale of love and misfortune.

Figure 18.5 The policeman, Wai (Eric Tsang) watches Hai'er’s video letter to her husband, recorded between 1997 and 1999.

Chan’s short film continues the most striking motifs of the ghost wife in East Asian literature and film: the necromantic romance as a framework for pursuing the question of faithfulness in love in the context of historical change, epitomized by Stanley Kwan’s 1987 film Rouge (Chow 1993; Lim 2001). Over the last two decades, critical paradigms surrounding the inscription of local Hong Kong history in supernatural narratives have emphasized reflectionist readings in relation to the 1997 handover and the dovetailing of the spectral with the nostalgic. Though such an approach has arguably become a critical commonplace, it does remind us that at a crucial juncture the ghost film registered the singularity of Hong Kong’s fateful return to mainland Chinese governance, a return that both refused to conform to prevailing narratives of nationalist decolonization and highlighted a sense of both time and place as recalcitrant to linear chronology and homogeneous space (Lim 2009: 182–188). As a post-handover film, Going Home at once revisits some of the concerns of nostalgic ghost allegories made prior to 1997 as well as gesturing towards the regionalist/globalist aspirations that coincided with Hollywood’s frenzied remaking of the “Asian horror film” in the following decade.

Going Home actors Leon Lai and Eric Tsang and cinematographer Christopher Doyle (in a cameo) had collaborated on a prior Peter Chan film, the 1996 melodrama Comrades, Almost a Love Story, a film that also considered the vexed pre-handover relationship of Hong Kong and the mainland via New Hong Kong cinema’s thematic of border crossing (Yau 1996). Going Home, however, introduces an interesting departure from this prior intertextual template: here, the mainland couple who migrate to Hong Kong are homesick zhongyi physicians. In two parallel, equally problematic moves, the film figures China as a repository for outmoded medical traditions while portraying Hong Kong as a place of inevitable death for mainland Chinese migrants. The mainland protagonists die repeatedly in the port city, ultimately unable to go home. Such representational logics are not only temporalized by the ghost film’s spectral time (Lim 2009: 151–155), but also exemplified by a figure – traditional Chinese medicine – that emerges as translocal and transtemporal by definition.

Dumplings: Medicinal Meals and Cannibal Allegories

Director Fruit Chan underscores the local and historical specificity of the Hong Kong setting in Dumplings. The decrepit Kowloon building where much of the film is set, Chan speculates in an interview, dates from “the first generation of public housing in Hong Kong” (Trbic 2005). Esther Cheung has noted the centrality of abandoned public housing estates in the cinema of Fruit Chan’s films, such as Made in Hong Kong (1997), The Longest Summer (1998), and Dumplings. These dilapidated tenements are home to the most disenfranchised and marginalized subjects: migrants, the aged, and the poor. Cheung writes:

The housing estate in Dumplings is in Shek Kep Mei. It is the oldest type of public housing in Hong Kong, shabby, poor, and nearly forsaken… The derelict low-cost housing estates in Dumplings have become sites of [the] secret trafficking of desire,… done between Hong Kong and a southern city in China [Shenzhen] where postsocialism has generated cultural flows beyond anyone’s control

(Cheung 2009: 118).

In the feature-length version of Dumplings, a tarty-looking young woman who calls herself Aunt Mei (Bai Ling) carries a tiffin lunchbox across the Shenzhen border into Hong Kong.5 She unpacks its enigmatic contents in the privacy of her own kitchen in a run-down public tenement in Shek Kep Mei. While marinating the plump, shrimp-like ingredients in ginger water, Aunt Mei decides to eat one raw (see Figure 18.6). Though the kitchen scene is wordless, jarring noises on the soundtrack and the orange-pink of the curled dumpling meat cue the audience to sense that the freshly made, delectable-looking dumpling meat is abject. In this scene, as with the rest of the film, Dumplings’ spectatorial positioning is the opposite of conventional mirroring identification in genre films. Rather than encouraging spectators to mirror the protagonists’ pleasure in eating, the film solicits a negative affective response toward eating in most filmgoers for the duration of the film.

Figure 18.6 Aunt Mei (Bai Ling) eats raw dumpling meat in Dumplings (Fruit Chan, 2004).

Mrs. Li (Miriam Yeung), an incongruously well-dressed woman who desperately wants to recover her youthful appearance in order to stop her husband’s philandering, arrives at the dilapidated tenement. When Mrs. Li asks to sample Aunt Mei’s famously expensive dumplings, Aunt Mei boasts about the efficacy of her dumplings, emphasizing that true cures must be eaten. Obliquely yet unmistakably, this first conversation between the two women, the aging bourgeois Hong Kong housewife and the provocatively dressed young cook from mainland China, links eating to the promise of rejuvenation.

Food and medicine are closely linked in Chinese thought through nutritional practices (Farquhar 2002: 49); as such, the pervasiveness of medicinal meals in zhongyi and in Chinese everyday life is woven into the film’s details. Mrs. Li’s maid prepares tonic soup and black chicken; her high society friends, noticing her glowing, youthful appearance, speculate that she has been eating a diet of sheep placenta, reishi mushrooms, or snow lotus; and her husband, Mr. Li (Tony Leung Ka-fai) regularly eats boiled eggs that contain fertilized duck embryos, believed to boost virility and referred to by Filipinos and Malaysians as balut.

Only by degrees do we learn what Aunt Mei’s anti-aging dumplings are made of. Our worst suspicions are confirmed in a scene set in a Shenzhen hospital, where Aunt Mei meets with the nurse who supplies her secret ingredient. Aunt Mei’s dumplings, we realize with horror, are made out of human fetuses. Aunt Mei and the nurse were co-workers when the former was a practicing physician on the mainland. When her friend asks her why she broke up with her lover from those days, Aunt Mei (who is really Doctor Mei) replies that he was uncomfortable with the large number of abortions she conducted under China’s one-child policy. While North American viewers tend to see the film’s horrific representation of abortion in the context of debates over women’s reproductive rights (pro-choice versus pro-life movements), the film’s allusions signal a critique of the one-child policy and practices of sex-selective abortion and infanticide in mainland China.

Established in the late 1970s as a form of family planning and population control, the one-child policy was in place in the PRC (the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau were exempted) until changes relaxing the policy were announced in 2013 (Levin 2013).6 Abortions were legal under this policy, although sex-selective abortion, infanticide, and abandonment of unwanted children were not. Nonetheless, the cultural preference for sons, operating in tandem with the one-child policy, meant that female-selective abortion was widespread in China, resulting in a highly uneven sex ratio at birth (men far outnumber women; BBC News 2000). According to one estimate, about four million female fetuses have been aborted in China since the 1980s (Miller 2006: 514–517). As Yeh and Ng incisively point out, Aunt Mei is an abortionist-cum-cannibal entrepreneur who turns a profit from serving unwanted fetuses from China’s one-child policy to wealthy Hong Kong clients eager for eternal youth (Yeh and Ng 2009: 152–153).

In Dumplings, Aunt Mei’s explicit reference to the one-child policy and to the old collectivist adage, “serve the people,” add to an accumulating store of allusions to Communist Chinese history in the diegesis. Revolutionary icons of Maoist China are prominent in the eclectic collection of knickknacks on Aunt Mei’s sideboard; these purely visual allusions are never named in dialogue (Lu 2010: 184).7 Chuck Kleinhans usefully identifies the figures revealed in a panning shot as follows (see Figure 18.7):

Figure 18.7 Visual allusions to Maoist-era figures among Aunt Mei's eclectic collection of knickknacks: on the left, a female “barefoot doctor,” and Chairman Mao Zedong; on the right, a peasant woman wearing a Red Guard armband.

Mei’s collection of figurines includes (l. to r.) a female “barefoot doctor,” emblematic of the early revolutionary era when young volunteer semi-professionals went out to rural areas to deliver basic health care to the peasants. Chairman Mao Tse-tung in a salute, the Catholic Virgin Mary, several versions of Guan Yin… Also in the foreground, a cat teapot with the spout being its upraised paw. Continuing to pan right: a figure of a peasant militia woman with a Red Guard armband, marking her from the Cultural Revolution Era (1966–76); another Buddha and a Hello Kitty making the familiar beckoning gesture of the Maneki Neko (Japanese Fortune Cat)…

(Kleinhans 2007).

Clustered references to Maoism occur on the visual track rather than in dialogue, thus relying on the capacity of certain spectators – but not others – to recognize Maoist allusions in the film. Though Aunt Mei looks like a woman in her thirties, too young to have experienced the Cultural Revolution firsthand, a photograph taken in 1960, when she was 20, reveals that Mei is now actually 64 years old (see Figure 18.8). Aunt Mei is thus a living repository of socialist histories and an emblem of what Ackbar Abbas calls “posthumous socialism” in China:

Figure 18.8 Though Aunt Mei looks like a woman in her thirties, too young to have experienced the Cultural Revolution firsthand, a photograph taken in 1960, when she was 20 years old, reveals that Mei is actually 64 years old in the narrative present.

Even China’s description of itself – as a ‘Socialist Market Economy’ – is a catachresis… Are we dealing with another phase of socialism? Or, as is often said in the West, is China today capitalist in everything else but name alone? Or, more paradoxically, are we dealing with neither the life nor the death of socialism, but with its afterlife? With a posthumous socialism, more than a post-socialism… Socialism in posthumous form can have a vitality stronger than ever before

(2012: 11).

Abbas’s notion of posthumous socialism – a revenant possessing a “vital afterlife” in the People’s Republic – captures the sense of anomaly, of catachrestic aberrance, and anachronism (2012),8 embodied by Aunt Mei in Dumplings. Aunt Mei has a penchant for singing a revolutionary opera song, “Waves after Waves in Hongshu Lake,” (Kleinhans 2007: 5) that functions as a musical leitmotif in Dumplings. Aunt Mei refunctions the 1960s revolutionary song into a quasi-magical incantation of private enterprise, sung while her clients eat their macabre medicinal meal. Characterizing Aunt Mei as a “former red guard and current wild capitalist” who now serves as a “midwife” for an “extreme version of neoliberalism” in the era of market reform, Lu Tonglin convincingly reads the film as a scathing critique of the complacent coexistence of Maoist and post-Maoist histories within neoliberal consumer cultures in Hong Kong (Lu 2010: 194–196).

Aunt Mei is herself a product of such histories, having lived through various historical benchmarks: high Maoist socialism, the market economy, and the post-transitional period following the handover of Hong Kong governance to China. In contrast to the Cultural Revolution’s barefoot doctors (Valentine 2005; Zhang and Unschuld 2008), who were depersonalized embodiments of the socialist healthcare system, the economic liberalization that followed Dengist marketization from the late 1970s onwards saw the emergence of the private entrepreneurial (getihu) physician (Farquhar 1996: 246–247). Unlike the mainland doctors in Going Home, however, who trained purely in traditional Chinese medicine, Aunt Mei in Dumplings straddles both biomedicine and zhongyi, just as she regularly crosses the Shenzhen border between Hong Kong and mainland China. Her career change – from a biomedical doctor under Maoist rule to an entrepreneur of medicinal cannibalism in contemporary Hong Kong – complicates Going Home’s more stereotypical depiction of China and zhongyi as traditional and Hong Kong as contemporary.

Aunt Mei has lived through the Cultural Revolution, possibly as a barefoot doctor or as a Red Guard, like the figurines in her living room (see Figure 18.9). Allusions to her Maoist past color memorable shots of her and her clients eating, with great relish, her fetal dumplings. This spectacular indulgence of the appetites – for food, for youth, and for sex – is diametrically opposed to the collectivist asceticism of the Maoist era. The conflicted coevalness of Maoism and neoliberalism in both Hong Kong and mainland China is on grim display in the film’s cannibal feast.

Figure 18.9 A shot of Aunt Mei beside her sideboard, prominently featuring the figurines of Chairman Mao, a female “barefoot doctor,” and a female Red Guard.

In an interview on the set of Dumplings, director Fruit Chan explicitly links the medicinal meal to socially-accepted forms of therapeutic cannibalism, as exemplified by the mother’s ingestion of her baby’s placenta after delivery (Chan 2006).9 Though Fruit Chan’s examples are taken from China, recent journalistic coverage reveals that human placenta continues to be ingested for its supposed therapeutic effect in both Japan (Schaffer 2008) and Britain (Fearnley-Whittingstall 1999: 25–26). Tragically, the fictional Dumplings, based on Lilian Lee’s novella, “The Dumplings of Yue Mei’s Attic” turns out to have been chillingly prescient. In May 2012, the Los Angeles Times and other newspapers reported that 17,000 pills smuggled from China into South Korea and ingested as “health tonics” were composed of 99.7 percent human tissue, believed to have come from stillborn babies and aborted fetuses – mostly female – from China’s one-child policy (Los Angeles Times 2012).

The pursuit of youth and beauty is at heart a temporal fantasy: the dream of denying age, arresting time, and escaping change. In Dumplings, it also involves a perverse temporal reversal: a 64-year old woman regularly feasts on the unborn. This overturns the gendered, socially-validated practices of filial cannibalism of past centuries (gegouliaoqin) (Yue 1999: 69) to which Dumplings alludes, in which virtuous young women, usually daughters-in-law, cut off a portion of their own thigh to cook and serve to their husband’s ailing, elderly, and protein-deprived parents (Chong 1990: 93–99).10 The valence of cannibalism in China is thus (at least) two-pronged: on the one hand, like the incest taboo, cannibalism is a radical violation of the social order that re-inscribes the norm through its transgression. On the other, filial cannibalism is also “the ultimate gesture of social unity and filial devotion” (Rojas 2002). Though I have been considering the feature-length version of the film here, the shorter version of Dumplings released as part of Three…Extremes effects an even more striking reversal of the gendered and generational dynamics of filial cannibalism. Whereas young women throughout Chinese history have sacrificed their flesh for their elders, in the final scene of the shorter release version of Dumplings, a monstrous mother devours her own firstborn son.

In the feature-length version of Dumplings, Mrs. Li slowly becomes more and more like her dumpling supplier: a cannibal gourmand, her cravings intensify, and she presses Aunt Mei to procure the rarest, most expensive, and most potent delicacy of all: a five-month old fetus. Acceding to her wishes, Aunt Mei performs a dangerous and septic abortion in her own kitchen on Kate (Miki Yeung), an impoverished teenage girl molested by her own father. Kate bleeds to death after the abortion, collapsing in her mother’s arms on a public street. In addition to foregrounding the film’s critique of class inequalities (Kate’s death contrasts sharply with the aseptic conditions of the hospital abortion performed on Mr. Li’s mistress) (Johnston 2005), the chilling abortion scene establishes Aunt Mei’s cruelty towards other women.

As several commentators have noted, Dumpling’s emphasis on cannibalism as an allegorical vehicle for social critique owes a clear intertextual debt to a long discursive history of cannibalism in Chinese culture. This is most apparent in Aunt Mei’s monologue in defense of cannibalism in the feature-length version of the film, heard mostly as an offscreen voice-over:

You should never consider cannibalism immoral in China. It has existed since history began. Li’s Herbalist Handbook clearly stated that human flesh and organs are admissible ingredients for medical recipes.

During famines, neighbors traded and cooked each other’s children for survival. The famous chef Yi Ya heard that his emperor wanted to try human flesh. He butchered and served his son as a course to the monarch. Tales abound of caring sons and daughters cutting off flesh for their parents’ medicines. The classic Water Margin depicted heroes who savored their enemies. One even served buns with human flesh filling. The Japanese have definitely eaten many Chinese. You think our country could have got through all these wars and famines without consuming human flesh? What about out of pure hatred – to skin you and eat you alive? Our national hero Yue Fei once wrote, “Pep up with a meal of the invaders’ flesh. Celebrate with a drink of the invaders’ blood.” When two people are deeply in love, all they desire is to be inside each other. Inside each other’s guts.

Aunt Mei’s monologue is paired on the image track with overlapping editing of several shots that repeat, from various camera perspectives, the same sight: Aunt Mei serving dumpling soup to first time customer Mr. Li, a visualization of the logic of repetition-and-difference underpinning her own erudite recital of literary and historical allusions. In the context of the diegesis, Aunt Mei’s monologue functions as an exercise in self-justification addressed to a new client. Extra-diegetically, this speech is directed at the audience, explicitly alerting us to the film’s conscious use of what Carlos Rojas calls a “shared discourse of cannibalistic allusions” with deep historical roots in Chinese culture (Rojas 2002). As Lu persuasively argues, Dumplings recalls the most influential allegorical treatment of cannibalism in modern Chinese literature, Lu Xun’s short story, “Diary of a Madman” (Lu 2010: 188), which similarly referred to cannibalism in the Chinese classics. Diary of a Madman is widely considered a germinal expression of “anti-traditionalism as a revolutionary ethos” in the May Fourth movement (Tang 1992: 1222).

Published in 1918, “Diary of a Madman” chronicles the diarist’s escalating paranoia as he becomes convinced that everyone in his community, including his own brother, is a cannibal. Once the diarist comes to his first epiphany, “they eat humans, so they may eat me,” his perspective both on his immediate family and China’s millennial history changes. Realizing that cannibalism has been practiced since “ancient times,” the madman discerns a two word injunction between the lines of history books and Confucian classics: “Eat people” (Lu 1960, 1972). Read allegorically, the well-known anti-traditional stance of Lu Xun as a May Fourth writer comes through most clearly in the diarist’s desperate plea to the cannibals around him to break with China’s feudal past. This allegorical reading of “Diary of a Madman” has become canonical: Lu Xun’s story is acknowledged to be a scathing indictment of the desperation and brutality to which China had devolved in the late imperial and post imperial period, becoming a “terrible self-cannibalistic China” that preys upon its own weakest citizens (Jameson 1986: 70–74). The story ends on a despairing note as the madman worries that the future itself might be irredeemably compromised by cannibalism: “Save the children…” (Lu 1960, 1972) To Lu Xun’s exhortation in 1918, Dumplings in 2004 offers a pessimistic rejoinder: cannibalism is a thriving transborder economy a century later; far from being saved, children are eaten before they are born. In representing contemporary consumer culture in Hong Kong and mainland China as cannibalistic, Dumplings inherits a line of social critique that runs from the May Fourth era to Maoist revolution to economic liberalization. But whereas Lu Xun’s madman voiced the May Fourth critique of feudal Confucian tradition, Aunt Mei deploys the discursive history of Chinese cannibalism to legitimize neoliberal rationality (Lu 2010: 194).

On the level of individual authorship, the incongruity of oppositional filmmaker Fruit Chan’s involvement in the pan-Asian Three franchise has been noted by several critics (Johnston 2005; Lu 2010:179). True to his auteur persona as an independent filmmaker seeking “to create [an] alternative space within the mainstream” (Cheung 2009:32), Fruit Chan delivers in Dumplings an acerbic critique of the neoliberal imperative. In Dumplings, all the protagonists are simultaneously antagonists; rather than focalizing the film around a virtuous and victimized moral center, the central characters are all calculative, entrepreneurial, neoliberal cannibals. Set adrift without a morally ascendant hero to identify with, viewers confront Aunt Mei, an extreme version of what Wendy Brown dubs Homo oeconomicus, a citizen–subject called into being by neoliberal governmentality (Brown 2003).

Multilingualism, Pan-Asian, and Pan-Chinese Cinema

In a 2002 interview for the Harvard Asia Quarterly, Jin Long Pao asked Peter Chan whether or not “Asia’s linguistic diversity” should be considered a “barrier” to pan-Asian cinema. Peter Chan replied:

A lot of people will tell you the problem is language, but I strongly disagree. Hollywood films control 80 percent of the market share in Asia, and they are in English. And don’t kid yourself, not everybody reads and speaks English in Asia – a lot of people read subtitles. And then you say it’s because people are used to English due to years of exposure to American movies. But then again, why can’t they get used to the Thai language or the Korean language?

(Jin 2002).

Citing the success of subtitled Hollywood films among Asian audiences who are not conversant in English, Peter Chan implicitly adverts to translational processes (e.g., subtitles) in maintaining that linguistic differences pose no real obstacle to the success of pan-Asian cinema. This might explain the pronounced use of multilingualism in certain pan-Asian film projects spearheaded by Applause (see Knee 2009 for a discussion of multilingualism in The Eye [Pang Brothers, 2002]).

The transborder narratives of Going Home and Dumplings feature bilingual Chinese protagonists who converse in Cantonese (the lingua franca of Hong Kong) and Mandarin Chinese (standard Mandarin or putonghua is the official language of both China and Taiwan and is based on variants spoken in northern and southwestern China). In Going Home, the married couple from the mainland, Yu and Hai’er, converse only in Mandarin with one another, while the Hong Kong-born policeman Wai speaks only Cantonese throughout the film. Dr. Yu, the husband, alternates between Mandarin and Cantonese when talking to the policeman. In Dumplings, Mrs. Lee always speaks in Cantonese to Aunt Mei, who replies to her Hong Kong clients in Mandarin peppered with snatches of Cantonese.

Interestingly, there are no scenes of overt translation in either Going Home or in Dumplings because the principal characters are assumed to be bilingual. One character begins a conversation in Cantonese to which another protagonist replies in putonghua, without the need for a third person to act as a translator or and without recourse to a shared third language. The ease with which the bilingual conversations occur between characters, coupled with the seamlessness of monolingual subtitles that do not identify the languages being spoken, all work to efface the work of translation and the presence of multilingualism for audiences unfamiliar with how these different languages sound. For moviegoers who can’t distinguish between the sound of spoken Mandarin and Cantonese languages, the characters are conversing in the same, undifferentiated Chinese.

Failing to hear the play of Cantonese and Mandarin in either film, however, means missing a rich layer of meaning in the transborder narrative. Language selection in cinema has always been political in the context of the linguistic heterogeneity of “Greater China.” The establishment of Communist rule in China in 1949 led to the devaluation of all other Chinese languages as “dialects” and the official adoption of putonghua for all mass media forms (Pang 2010: 149). In such a context, as Lo Kwai-cheung emphasizes, the “idiosyncratic use” of Cantonese by Hong Kong people, “its intractability to the taming by standard Chinese,” is an inscription of local identity that becomes even more significant in the post-handover period. If the 1997 handover of Hong Kong governance to the PRC inscribed a problematic fantasy of “reunifying a Chinese subject,” then the co-presence of Cantonese and Mandarin in Dumplings and Going Home highlights the internal contradiction and cultural heterogeneity that Hong Kong introduces to the presumed stability of “Chineseness” as a racial–cultural-national category of identity (Lo 1998: 152–153).

Though diegetically concerned with character relationships between Hong Kong locals and migrants from mainland China, neither Going Home nor Dumplings is a transborder-co-production with China. Released in 2002 and 2004, both films precede the 2008 implementation of CEPA V, the mainland and Hong Kong Closer Economic Partnership Agreement, which allows Hong Kong’s domestic market to include all of Guangdong Province and amounts to official recognition of linguistic and cultural difference within the national self (Pang 2010: 142). Although they are not transborder co-productions, Going Home and Dumplings nonetheless have pan-Chinese appeal, using bilingualism to interpellate audiences in mainland China, Hong Kong, and overseas. 11 For example, pan-Chinese audiences notice visual puns unremarked by either dialogue or subtitling but prominent for viewers who can read written Chinese script: because the words “four” and “death” are homophones in Chinese (the pronunciation of the two characters sound the same), viewers who see “fourth floor” emblazoned outside Aunt Mei’s apartment in key scenes are given forewarning that she is an ominous figure dealing in a deathly trade12 (see Figure 18.10).

Figure 18.10 Establishing shots of Aunt Mei's tenement read as a visual pun, since “fourth floor” is a homophone for “death floor” in spoken Chinese.

Conclusion

Going Home was the Hong Kong contribution to the first omnibus pan-Asian film release, Applause Pictures’ Three, which also contained episodes from South Korea (Memories, dir. Kim Jee-woon, b.o.m. film productions), and Thailand (The Wheel, dir. Nonzee Nimibutr, Cinemasia). The second installment in the anthology franchise, Three…Extremes offered episodes from Japan (Box, dir. Takashi Miike, Kadokawa Pictures), South Korea (Cut, dir. Park Chan-wook, b.o.m. film productions), and Hong Kong (Dumplings).

As has often been noted, the number “three” in the franchise title refers not only to the three different short films and directors brought together in the anthology format, but also refers to the franchise’s attempt to multiply its market address threefold. As Peter Chan put it, “The philosophy of Three is to make a film that can be popular in three places.” Aware that market proximity (Yeh and Davis 2002: 67) – a sense of familiarity with another nation’s screen texts – varies across markets, the franchise attempts to use a local product’s recognizable setting, director, language, and stars to win over audiences who might otherwise have been hesitant to watch movies from an unfamiliar national cinema (Chow 2002: 5).

The success of the pan-Asian recipe adopted by the Three franchise was limited and uneven. As with J-horror, DVD distribution (e.g., Tartan Extreme) rather than theatrical exhibition was the primary mode of regional and global circulation for both Three and Three Extremes (Lee 2011: 105–110; Wada-Marciano 2009: 26).13 Nonetheless, a consideration of the franchise’s theatrical box office performance might prove instructive. Although the South China Morning Post reported that Three was a box office success in Thailand (Chow 2002: 5), its box-office performance in South Korea was considered a disappointment by b.o.m. film productions. The Hong Kong segment Going Home was the best received of the three episodes in South Korea (Lee 2011: 107). Davis and Yeh report that in terms of overall box office performance on the local (Hong Kong), regional (intra-Asian), and global scales, Three and Three…Extremes lagged well behind The Eye, “by far Applause’s most commercially successful film” (Davis and Yeh 2008: 95–96). Dumplings and Going Home, both re-released in feature-length versions that garnered awards in Hong Kong and Thailand and broad critical acclaim, demonstrate that generic reinvention combined with a hybrid “commercial art film” aesthetic could bring visibility and status to these films and to Applause itself (Davis and Yeh 2008: 94–95). These films’ fascinating weave of culturally-specific allusions, on the one hand, and attempts at pan-Asian appeal, on the other, resulted in limited box office success alongside a warm critical reception for both Going Home and Dumplings. In closing, I would speculate that this outcome is partly rooted in the dual structure of a cinema of allusion (Carroll 1982: 56).

In its pan-Asian incarnation in Going Home and Dumplings, the cinema of allusion actualizes a two-tiered system of address: first, genre pictures for regional and global audiences unfamiliar with the films’ references but able to appreciate the films’ reworking of the horror genre’s themes and conventions; and second, an intertextual work for “informed viewers” (Carroll 1982: 52–53) familiar with these culturally specific references and thus able to retrace the expressive reservoir from which both films draw.

In terms of the first mode of audience address – reworking genres in order to address regional and global audiences – generic experimentation can be risky for films that need to close the gap between the (foreign) work and the (local) audience. Particularly in the case of Dumplings and Going Home, several observers have remarked that the films neither adhere to horror film conventions nor deliver the generic expectations raised by the labels “Asian horror” or “Asia extreme,” the latter being a loose umbrella category minted by Tartan Asia Extreme’s genre-branding, which distributed Three and Three…Extremes on DVD (Lee 2011: 106; Johnston 2005).

In terms of the second mode of audience interpellation, Dumplings and Going Home make heavy demands upon a culturally and historically knowledgeable viewer who can activate reading protocols attuned to the films’ rich allusive texture, their zhongyi motif, strong Maoist charge, and bilingualism. Such exegetical pleasures are likely to exert great appeal for serious students of film, which may account for the critical acclaim and scholarly interest these films have enjoyed. To the degree that they might, on hindsight, be recognized as testing out the possibilities of a pan-Asian cinema of allusion, Dumplings and Going Home exemplify the delicate balancing act such filmmaking requires: to speak broadly to all while speaking obliquely to some, a dynamic of audience inclusion and exclusion that is fascinating in its contradiction.

A political fantasy about audiences is at work in the framing of Going Home and Dumplings; this fantasy mingles both actual and potential social relations. Pan-Asian cinema is pitched at actual markets, but its production and marketing are driven by imaginary projections of how diverse viewers will really engage or consume these films. The potential mismatch between market projections and actual reception is the wager hazarded by a pan-Asian cinema of allusion.

References

- Abbas, Ackbar (2012), “Adorno and the Weather: Critical Theory in an Era of Climate Change,” Radical Philosophy 174 (July/August): 7–13.

- Bates, Don G. (2006), “Why Not Call Modern Medicine ‘Alternative’?,” in Health and Healing in Comparative Perspective (ed. Elizabeth D. Whitaker), Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006, 29–40.

- BBC News (2000), “China Steps up ‘One Child’ Policy,” BBC News (September 25), http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/941511.stm. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- Benjamin, Walter (1977), “A Short History of Photography,” (trans. Phil Patton), Artforum 15.6 (February): 46–61.

- Brown, Wendy (2003), “Neo-Liberalism and the End of Liberal Democracy,” Theory and Event 7.1, http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/theory_and_event/v007/7.1brown.html. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- Carroll, Noël (1982), “The Future of Allusion: Hollywood in the Seventies (and Beyond),” October 20 (Spring): 51–81.

- Chan, Fruit (2006), The Making of Dumplings, Producers: Adam Wong and Dominie Ting; Videographer: Vincent Cheung, in Three Extremes DVD [2-Disc Special Edition, US Version], Lions Gate Home Entertainment.

- Cheung, Esther (2009), Fruit Chan’s Made in Hong Kong, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Ching, Leo (2000), “Globalizing the Regional, Regionalizing the Global: Mass Culture and Asianism in the Age of Late Capital,” Public Culture 12.1 (Winter): 233–257.

- Chong, Key Ray (1990), Cannibalism in China, Wolfeboro, NH: Longwood Academic.

- Chow, Rey (1993), “A Souvenir of Love,” Modern Chinese Literature 7: 59–76.

- Chow, Vivienne (2002), “Three of a Kind,” South China Morning Post (August 15), sec. 5: 5.

- Cochran, Sherman (2006), Chinese Medicine Men: Consumer Culture in China and Southeast Asia, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Curtin, Michael (2010), “Introduction,” [Special Section, “In Focus: China’s Rise”], Cinema Journal 49.3 (Spring): 117–120.

- Davis, Darrell William and Emilie Yueh-Yu Yeh (2008), East Asian Screen Industries, London: BFI.

- Farquhar, Judith (1996), “Market Magic: Getting Rich and Getting Personal in Medicine After Mao,” American Ethnologist 23: 239–257.

- Farquhar, Judith (2002), Appetites: Food and Sex in Postsocialist China, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Francois and Sonatine (2003), “Interview: Peter Chan,” Cinemasie.com (January), http://www.cinemasie.com/en/fiche/dossier/70/. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- Ge, Sun (2000), “How Does Asia Mean? (Part 1),” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 1.1: 13–47.

- Hau, Caroline S. and Takashi Shiraishi (2013), “Regional Contexts of Cooperation and Collaboration in Hong Kong Cinema,” in Popular Culture Co-Productions and Collaborations in East and Southeast Asia (eds. Nissim Otmazgin and Eyal Ben-Ari), Singapore and Kyoto: National University of Singapore Press and Kyoto University Press, 68–96.

- Hilderbrand, Lucas (2009), Inherent Vice: Bootleg Histories of Videotape and Copyright, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Fearnley-Whittingstall, Hugh (1999), “Save Some Womb for Dessert,” Harper’s Magazine (February): 25–26.

- Jameson, Fredric (1986), “Third-World Literature in the Era of Multinational Capitalism,” Social Text 15 (Autumn): 65–88.

- Jin, Long Pao (2002), “The Pan-Asian Co-Production Sphere: Interview with Director Peter Chan,” Harvard Asia Quarterly 6.3 (Summer).

- Johnston, Ian (2005), “Compliments to the Chef: Three … Extremes’ Dumplings Expertly Mixes Social Critique and Questionable Cuisine,” Bright Lights Film Journal 48 (May), Accessed January 12, 2015.

- Kleinhans, Chuck (2007), “Serving the People – Dumplings,” Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media 49: 5, http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc49.2007/Dumplings/5.html. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- Knee, Adam (2009), “The Pan-Asian Outlook of The Eye,” in Horror to the Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema (eds. Jinhee Choi and Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano), Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 69–84.

- Korhonen, Pekka (2008), “Common Culture: Asia Rhetoric in the Beginning of the 20th Century,” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 9.3: 395–417.

- Lee, Nikki J.Y. (2011), “‘Asia’ as Regional Signifier and Transnational Genre-Branding: The Asian Horror Omnibus Movies,” in East Asian Cinemas: Regional Flows and Global Transformations (ed. Vivian P.Y. Lee), Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 103–117.

- Lei, Sean Hsiang-Lin (2002), “How Did Chinese Medicine Become Experiential? The Political Epistemology of Jingyan,” positions: east asia cultures critique 10.2: 333–364.

- Levin, Dan (2013), “Many in China Can Now Have a Second Child, but say No”, The New York Times (February 25), http://nyti.ms/1kbF81u. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- Lim, Bliss Cua (2001), “Spectral Times: The Ghost Film as Historical Allegory,” positions: east asia cultures critique 9.2 (Fall): 287–329.

- Lim, Bliss Cua (2009), Translating Time: Cinema, the Fantastic, and Temporal Critique, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Lim, Kean Fan (2006), “Transnational Collaborations, Local Competitiveness: Mapping the Geographies of Filmmaking in/through Hong Kong,” Geografiska Annaler [Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography] 88 B 3: 337–357.

- Lo, Kwai-Cheung (1998), “Look Who’s Talking: The Politics of Orality in Transitional Hong Kong Mass Culture,” boundary 2 25.3 (Autumn): 151–168.

- Los Angeles Times (2012), “South Korea: Confiscated ‘Health’ Pills Made of Human Remains,” Los Angeles Times (8 May), http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/world_now/2012/05/south-koreans-confiscated-pills-human-remains.html. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- Lu, Tonglin (2010), “Fruit Chan’s Dumplings: New ‘Diary of a Madman’ in Post-Mao Global Capitalism,” The China Review 10.2 (Fall): 177–200.

- Lu, Xun (1960, 1972), “A Madman’s Diary,” Selected Stories of Lu Hsun, http://www.marxists.org/archive/lu-xun/1918/04/x01.htm. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- Miller, Barbara D. (2006), “Female-Selective Abortion in Asia: Patterns, Policies, and Debates,” in Health and Healing in Comparative Perspective (ed. Elizabeth D. Whitaker), Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 887–913.

- Otmazgin, Nissim (2013), “Popular Culture and Regionalization in East and Southeast Asia,” in Popular Culture Co-Productions and Collaborations in East and Southeast Asia (eds. Nissim Otmazgin and Eyal Ben-Ari), Singapore and Kyoto: National University of Singapore Press and Kyoto University Press, 29–51.

- Pang, Laikwan (2010), “Hong Kong Cinema as a Dialect Cinema?,” Cinema Journal 49.3 (Spring ): 140–143.

- People’s Daily (2000a), “Thailand Legitimizes Traditional Chinese Medicine,” People’s Daily Online [English edition] (July 1), http://en.people.cn/english/200007/01/eng20000701_44446.html. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- People’s Daily (2000b), “Traditional Chinese Medicine Gets Popular in SE Asia: Thai Expert,” People’s Daily Online [English edition] (September 19), http://english.people.com.cn/english/200009/19/eng20000919_50837.html. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- Rojas, Carlos (2002), “Cannibalism and the Chinese Body Politic: Hermeneutics and Violence in Cross-Cultural Perception,” Postmodern Culture 12.3, http://pmc.iath.virginia.edu/issue.502/12.3rojas.html. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- Schaffer, Amanda (2008), “The Tissue of Youth: Is Human Placenta a Wonder Drug, or Is It Just Another Japanese Health Fad?,” Slate (30 December), http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/medical_examiner/2008/12/the_tissue_of_youth.html. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- Tang, Xiaobing (1992), “Lu Xun’s ‘Diary of a Madman’ and a Chinese Modernism,” PMLA 107.5 (October): 1222–1234.

- Teo, Stephen (2008), “Promise and Perhaps Love: Pan-Asian Production and the Hong Kong–China Interrelationship,” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 9.3: 341–358.

- Trbic, Boris (2005), “The Immortality Blues: Talking with Fruit Chan About Dumplings (Interview),” Bright Lights Film Journal 50 (November), http://www.brightlightsfilm.com/50/fruitiv.php. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- Valentine, Vikki (2005), “Health for the Masses: China’s ‘Barefoot Doctors’,” NPR: National Public Radio (5 November), http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4990242. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- Wada-Marciano, Mitsuyo (2009), “J-Horror: New Media’s Impact on Contemporary Japanese Horror Cinema,” in Horror to the Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema (eds. Jinhee Choi and Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano), Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 15–37.

- Yau, Esther (1996), “Border Crossing: Mainland China’s Presence in Hong Kong Cinema,” in New Chinese Cinemas: Forms, Identities, Politics (eds. Nick Browne, et al.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 180–201.

- Yeh, Emilie Yueh-Yu and Neda Hei-tung Ng (2009), “Magic, Medicine, and Cannibalism: The China Demon in Hong Kong Horror,” in Horror to the Extreme: Changing Boundaries in Asian Cinema (eds. Choi Jinhee and Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano), Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 145–160.

- Yeh, Yueh-Yu and Darrell William Davis (2002), “Japan Hongscreen: Pan-Asian Cinemas and Flexible Accumulation,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television 22.1: 61–82.

- Yu F., T. Takahashi, J. Moriya et al. (2006), “Traditional Chinese Medicine and Kampo: A Review from the Distant Past for the Future,” The Journal of International Medical Research 34: 231–239.

- Yue, Gang (1999), The Mouth That Begs: Hunger, Cannibalism, and the Politics of Eating in Modern China, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Zhan, Mei (2009), Other-Worldly: Making Chinese Medicine through Transnational Frames, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Zhang, Daqing and Paul Unschuld (2008), “China’s Barefoot Doctor: Past, Present, and Future,” The Lancet 372 (November 29): 1865–1867, http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736%2808%2961355-0.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2015.

- Zhang, Yanhua (2007), Transforming Emotions with Chinese Medicine: An Ethnographic Account from Contemporary China, Albany, NY: SUNY Press.