Zahra, Colonel Ali Kannas See HAMIDI, IBRAHIM AL-.

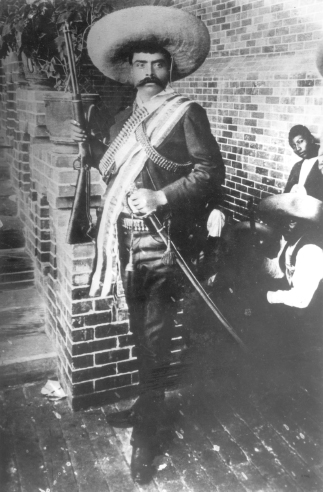

A Mexican revolutionary of Native American birth, Emiliano Zapata is considered by many as the noblest hero of the country’s revolutionary and civil wars that raged from 1910 to 1920. As a youth, his radical spirit was molded by comparing the dirt-floor hovel in which he lived while working as a stable hand on a large hacienda to the clean, tiled stables provided for the horses in his charge.

In 1897 he became a leader in a peasants’ protest against the hacienda that had appropriated their land. Arrested and then released, Zapata continued his activities and was finally drafted into the army. That tour of duty did not cool his revolutionary ardor, and by 1909 he was president of the board of defense for his village and soon led peasants on campaigns that seized hacienda lands and restored them to the people.

Meanwhile Francisco Madero had launched a revolution against the reactionary national government of Porfirio Díaz, and Zapata eagerly joined that campaign, not, however, abandoning his own rebellion. He soon came to regard Madero’s reform programs as far too moderate. Still, Zapata played a key role in defeating the counterrevolution under General Victoriano Huerta. His forces, known as the Liberation Army, numbered 25,000, and after Huerta’s flight, Zapata notified the more moderate revolutionaries under Venustiano Carranza and Alvaro Obregón that he would continue his own revolutionary struggle. In that he was supported by another revolutionary, the often savage Pancho Villa. Zapata’s forces were responsible for a number of brutal excesses, but these often paled compared to those of almost all other armies on both sides. When in 1914 the Zapatistas occupied Mexico City, his men did not commit the bloody actions that had turned the populace against all the other forces of the period. Historian Ronald Atkin described their behavior: “But the Army of the South made no attempt to loot stores or homes, even though their meager rations were soon exhausted. Instead they knocked on doors, asking humbly for a little food, or approached a passerby to beg a peso.”

Efforts by the Carranza forces to buy off Zapata proved without avail, and Zapata was destined to die poor. However, in the ensuing struggles, Carranza and the independent Obregón forces gained the military advantage, weakening Villa especially. Zapata also was weakened but still remained master of his own territory. Finally, Carranza became constitutional president in 1917 and determined to wipe out all the rebels. He sent General González to Morelos to destroy Zapata. Zapata met the challenge on the battlefield, and as government troops burned villages and crops and hanged peasants, Zapata warred on the haciendas, putting great numbers to the torch. The result was a genuine Mexican standoff, González controlling the cities but Zapata the king of the hills.

Finding himself unable to overcome Zapata’s masterful guerrilla tactics, González turned to duplicity and sent Colonel Jesus Guajardo to feign interest in joining Zapata. Zapata could not help but be interested since it would mean the addition of 800 soldiers and much-needed munitions. Guajardo demonstrated his sincerity to Zapata by actually seizing a town occupied by government troops and killing many of them in a fake mutiny. Among the federals Guajardo captured were 50 former Zapatistas who had previously gone over to the government and provided much assistance against Zapata. In a further demonstration of his good faith, Guajardo had these expendable 50 executed on the spot.

That evening Zapata, with a heavy guard, met Guajardo for the first time. Guajardo presented Zapata with a handsome sorrel stallion, and Zapata agreed that they would meet the following day at the Chinameca hacienda to plan their joint actions. On April 10, 1919, Zapata arrived with 150 men, but entered the hacienda with only 10 of them. The rest remained outside to guard the hacienda, since it was believed federal forces might be in the area.

Inside the hacienda Guajardo’s men assembled in “present arms” formation to honor Zapata. The bugle sounded three times, at the end of which the massive formation turned their guns on Zapata, who fell from the sorrel riddled with bullets. His 10 companions were all killed or wounded, and his soldiers outside had no choice but to flee.

General González, who had masterminded the ambush, notified President Carranza of its success the same day. The president replied: “I received with satisfaction your report telling of the death of Emiliano Zapata as a result of the plan executed so well by Colonel Jesus M. Guajardo. . . . Because of Colonel Guajardo’s conduct I have dictated … a promotion in grade for Colonel Guajardo and his officers.”

While it can be said that the movement for immediate land reform died with Zapata, his death gave birth to a legend and slogan that has long survived him— Tierra y libertad, or “Land and Liberty.” Zapata’s name is now inscribed in gold in the Mexican Chamber of Deputies.

The killings did not stop with Zapata. In May 1920 Carranza was assassinated by followers of Obregón, who then came to power. Caught in the changing tides of power, General González was imprisoned and Colonel Guajardo went before a firing squad, not for the assassination of Zapata but allegedly for seeking to free González. (See ALSO CARRANZA, VENUSTIANO; OBREGÓN, ALVARO; VILLA, PANCHO.)

Further reading: Zapata, by Roger Parkinson; Zapata and the Mexican Revolution, by John Womack; Heroic Mexico, by William Weber Johnson.

Considered by many as the noblest hero of Mexico’s revolutionary and civil wars, Emiliano Zapata was lured into a trap by an army officer pretending to have defected.

General Joaquín Zenteno Anaya, the Bolivian ambassador to France, was gunned down by terrorists on a Paris street on May 11, 1976. Following the assassination, a group identifying itself as the International “Che” Guevara Brigade issued a telephone communiqué to Agence France-Presse, the French news service, declaring the murder was in retaliation for the 1967 slaying of Ernesto “Che” Guevara. Zenteno had commanded the controversial expedition that killed the Latin American revolutionary in Bolivia.

The story made a neat little package, but other possible motives for the Zenteno killing came to the surface. Zenteno was alleged to have been deeply involved in attempts to prevent the French government from seeking the extradition from Bolivia of German war criminal Klaus Barbie.

In Buenos Aires six days after the killing, General Luis Reque Teran, who had commanded the army division that tracked down Guevara’s guerrilla band, charged that the killing of Zenteno had been ordered by rightist Bolivian president Hugo Banzer Suarez. General Reque had previously charged that the Guevara execution had actually been ordered by General Alfredo Ovando Candia, who later became president of Bolivia.

Bolivia’s current army commander, General Raúl Alvarez, denounced Reque for revealing “military secrets,” and stated that he would be dismissed from the army for treason and that his revelations had led to Zenteno’s assassination—a peculiar statement since Zenteno’s position had been well publicized at the time of Guevara’s slaying.

Reque countered that in addition to the Zenteno murder, Banzer and Alvarez were guilty of “genocide” in the slaying of hundreds of political prisoners and Bolivian peasants.

President Banzer warned the Bolivian press that he would impose sanctions on the media after they published accounts of the charges made by Reque. On May 22 radio stations and newspapers went on strike across the country in protest to Banzer’s threat, which he then withdrew.

Who had really ordered Ambassador Zenteno’s assassination was left unclear. (See TORRES, JUAN JOSE.)

General Ziaur Rahman, who became president of Bangladesh after the assassination of the country’s first chief executive, Sheik Mujibur Rahman, in 1975, was himself assassinated on May 30, 1981. President Ziaur, two aides, and six bodyguards were all slain after they had gone to sleep in a guest house in Chittagong. The assassination represented an unsuccessful coup attempt led by Major General Manzur Ahmed, whose power base was in the city of Chittagong.

Hours after the assassination Manzur went on radio to announce the firing of the army chief of staff and eight other generals. However, much of the army remained loyal to Ziaur’s memory as well as to 75-year-old Vice President Abdus Sattar in the capital city of Dacca. When after two days of bloody fighting—50 police officers in Chittagong alone were killed—it became apparent the rebels were not gaining strength, General Manzur and some of his supporters fled the city. On June 1 Manzur and two other high-ranking generals were captured by government soldiers, and it was announced the following day that after their arrests the trio had been killed by enraged guards.

Ziaur was buried on a plot before the parliament building in Dacca. Although he ran a stern, even brutal regime, Ziaur was credited with giving poverty-stricken Bangladesh some elements of stability. By the late 1980s most Bangladeshis were giving the late president positive ratings. However, his widow, Khaleda, who took over the reins of her husband’s political organization, had not been able to build a strong government. The same could be said of Sheik Hasina Wazed—the daughter of Bangladesh’s first leader, Mujibur—who assumed leadership of her father’s Awami League. Always in the background in Bangladesh was the threat of yet another military coup, since in the first 19 years of Bangladesh’s history no constitutional head of government had been able to complete a presidential term. (See MUJIBUR RAHMAN, SHEIK.)