25.1 Introduction

Since the earliest days of microbiology, it has been clear that all humans carry many of the same microbial lineages. The microbes living in or on our bodies are now known as the human microbiome (Turnbaugh et al. 2007). A collective international effort, called the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) by the National Institutes of Health (Peterson et al. 2009), is now broadly known as the International Human Microbiome Consortium (IHMC). The consortium is aiming to characterize the microbiome of various parts of human body.

Human body can support several bacterial ecosystems all over the body especially in hair (Tridico et al. 2014), skin, gut, mouth, and urogenital tracts (Giampaoli et al. 2012; Juusola and Ballantyne 2005). Different studies for gut microflora showed extensive diversity of the gut microbiome between healthy humans (Ley et al. 2006a, b; Raman et al. 2010). Studies since past 5 years for skin bacterial diversity showed that in addition to conserved organisms, there is massive diversity in identities and richness (Costello et al. 2009; Grice et al. 2009; Fierer et al. 2008; Gao et al. 2007; Blaser 2010). Among these, the oral cavity is a unique ecological niche because it can provide hard, non-shedding surfaces that are teeth which are durable and accessible for microbial colonization. Our oral cavity harbors a diverse group of microorganisms that include bacteria, fungi, mycoplasma, protozoa, and sometimes may be viruses (Costello et al. 2009; Ventura Spagnolo et al. 2019). Altogether they are known as the oral microbiome. There are billions of bacteria in the oral cavity that forms ecosystems in different sites in the oral cavity. These ecosystems are dorsum of the tongue, buccal epithelium, the supragingival and subgingival tooth surfaces, crevicular surfaces, and tonsils where microflora varies from one site to another (Muhammad et al. 2012). These diverse ecosystems make saliva a rich source of a diverse group of bacteria.

25.2 Diversity of Oral Microflora

Our oral microflora constitutes more than 500 species of bacteria. The unique feature of oral bacteria is that they vary from mouth to mouth, though the majority of them are similar in most of the individuals and differences are created mainly by minority members of the bacterial group (Takeshita et al. 2016). More precisely diversity can be appreciated at species and subspecies level. A study by Bik et al. (2010) revealed how each oral cavity harbors a distinct population of microbial groups, but that such groups appear to be more identical when categorized at genus level. Previously designed ecological methods for larger species, such as co-occurrence evaluation, can significantly promote the study of diverse bacterial populations such as those present in the human body and improve our perception of the role of microbiome in human physiology.

25.2.1 Human Oral Microbiome Database (HOMD)

Human oral microbiome database is the first compiled human-associated microbiome characterization which offers resources for use in studying the microbiome’s function in health and disease. HOMD’s aim is to provide extensive information to the research community about nearly 700 prokaryote species that are found in the human oral cavity. HOMD is based entirely on a tentative naming scheme focused on the carefully curated 16S rRNA gene. The facility has sequenced more than 600 16S RNA gene libraries over the last 20 years and collected more than 35,000 clone sequences. The samples were collected from healthy individuals and participants with more than a dozen disease states such as caries, periodontal disease, endodontic diseases, and oral cancer. The HOMD ties data from sequences to phenotypic, phylogenetic, scientific, and bibliographic metadata. HOMD data structure, integration, and description may be used as a blueprint for microbiome data from other locations of the human body such as stomach, head, and vagina. Nearly 700 organisms are specified in the HOMD, of which 51% are officially listed, 13% are not mentioned (but cultivated), and 28% are recognized only as uncultivated phylotypes (http://www.homd.org, last accessed on 14 August 2020). There are about 150 genera, 700 species, in the HOMD collection. HOMD currently contains genomes for 400 oral taxa and even more than 1300 species of microorganisms.

Streptococcus, for instance, is a species with greater abundance than several genera (Butler et al. 2017). Streptococcus group has 43 species in the HOMD, 26 of which are named, 9 of which are not named, 7 are dropped, and 2 are lost.

Genomes for 30 oral taxa and 202 Streptococcus strains can be found on the HOMD. The genus Prevotella has 53 species in the HOMD, of which the genomes are accessible on HOMD for 32 species and 67 different strains. HOMD is focused on the microorganism cultivation. But constraint is quite a part of HOMD data’s oral microorganisms that cannot be cultivated, of which as much as 20–60% is reported to be uncultivable, due to the limitation of growth conditions, microbial interaction, and so on.

25.2.2 Factors Affecting the Diversity in Oral Microflora

- 1.

Time: Costello et al. (2009) have on four instances analyzed microbiome at 27 sites among seven to nine healthy persons. Such findings revealed that our microbiome has been customized, continuously varying between body environments and periods. In 300 healthy individuals in 18 body locations, the HMP Consortium has documented the composition and role of the human microbiome in 12–18 months. The populations in the oral cavity have become more variable over the duration of the sampling period (Anukam and Agbakoba 2017). In specimens from stable and vulnerable elderly people using 16S rRNA sequencing analysis, Ogawa et al. (2018) studied microbiome composition of saliva. The research proposed that overall weakness is related to the structure and development of oral microbiota.

- 2.

Age: The exciting fact about oral microflora is that it varies with age. Bacterial colonization in the oral cavity starts just a few hours after the birth. Microflora in the oral cavity changes continuously as various phases of teeth eruption and shedding goes on throughout the lifespan of a human because physiological changes take place each time a tooth erupts or sheds which changes the environment of oral cavity, leading to microbial shift (Xu et al. 2014). Table 25.1 illustrates different groups of bacteria colonizing the oral cavity as the age advances. This suggests that a unique group of bacteria can be cultivated or identified from the oral cavity of an individual at a particular age. Anukam and Agbakoba (2017) obtained oral specimens from three randomly chosen women aged 56, 28, and 8 years, isolated DNA, and amplified the 16S rRNA V4 region employing custom-coded primers prior to Illumina MiSeq sequencing. The study found that microbes with fluctuating diversity inhabited oral cavities in females of different ages. As the human life expectancy has increased with progress of medical science, An et al. (2018) researched the physiology of the aging and oral disease processes, anticipating that possible geriatric health studies will be funded and that further clinical work would take care of the significance of age.

- 3.

Diet: Lassalle et al. (2018) collected saliva from three pairs of hunter-gatherers and farmers living nearby in the Philippines. The findings indicated that significant dietary changes were selected for different commensal populations and were likely to play a role in the production of modern oral pathogens. Adler et al. (2013) have shown that the transformation from hunter-gatherer to farming has turned the oral microbial environment into a disease-related configuration. Modern oral microbial communities have been substantially less diverse than historical communities and can lead to post-industrial chronic oral diseases. Brito et al. (2016) correlated mobile genes present in 81 North American metropolises to 172 Fiji agrarians using a fusion of genomics with metagenomics from the single cell. They experienced significant distinctions between Fijian and North American microbiomes in their mobile gene material. These results show that the abundance of certain genes can reflect ecological selection. Many research studies of well-preserved dental calculus were engaged in an ancient oral microbiome to examine genomic innovations, diseases, etc. (Metcalf et al. 2013; Brown et al. 1976; Galvão-Moreira et al. 2018).

- 4.

Extreme environment: Brown et al. (1976) measured the preflight and postflight monitoring of changes in microbial populations at various intraoral sites. Microbiologic assessments showed noteworthy elevations in counts of specific anaerobic components of the oral microflora, Streptococci, Neisseria, Lactobacilli, and Enteric bacilli, which were believed to be diet related. The relative absence of hazardous intraoral changes to one’s wellness is regarded as this study’s most important result.

- 5.

pH of the Oral Cavity: pH for bacterial growth is one of the most significant considerations. The low pH change of the oral cavity induces a microbial shift owing to whatever explanation. The therapeutic significance of oral cavity pH and associated microflora dynamics is largely documented in the literature. Dental caries is attributed to acid in oral biofilms known as plaque formed by commensal microbes. The pH of the environment may be the consequence of the acidogenicity of bacteria coupled with or without the pH enforced by foreign sources, like food and beverages (Kianoush et al. 2014). The initial “substantial core model” research by Kianoush et al. (2014) establishes a pH-distinctive taxa and shows improvements in bacterial abundance in the acidic to neutral pH ranges. Some of the bacterial species have been shown to be capable of metabolic action under moderately acidic environments in oral cavity, both in proteolytic and in saccharolytic Prevotella sp. The microbial dynamics in oral cavities in healthy people and people with dental disorders such as caries became possible thanks to new NGS technologies (Zhou et al. 2017). A change in acid and acid-bacterial consortia, as seen in this research, namely Lactobacillus vaginalis and Streptococcus mitis, which favors caries lesions (Galvão-Moreira et al. 2018), was indicated to induce lower pH. The structural features of a bacterial salivary population are affected by the pH (Zhou et al. 2017).

- 6.

Host defense: Growth of bacteria is mostly influenced by the immune system of the individual. The immune system keeps the growth of bacteria in control to prevent it from causing disease. It generally depends on the genetic makeup of the individual. Every human body reacts differently to various microbes. So some bacteria can grow more preferentially in some individuals than others.

- 7.

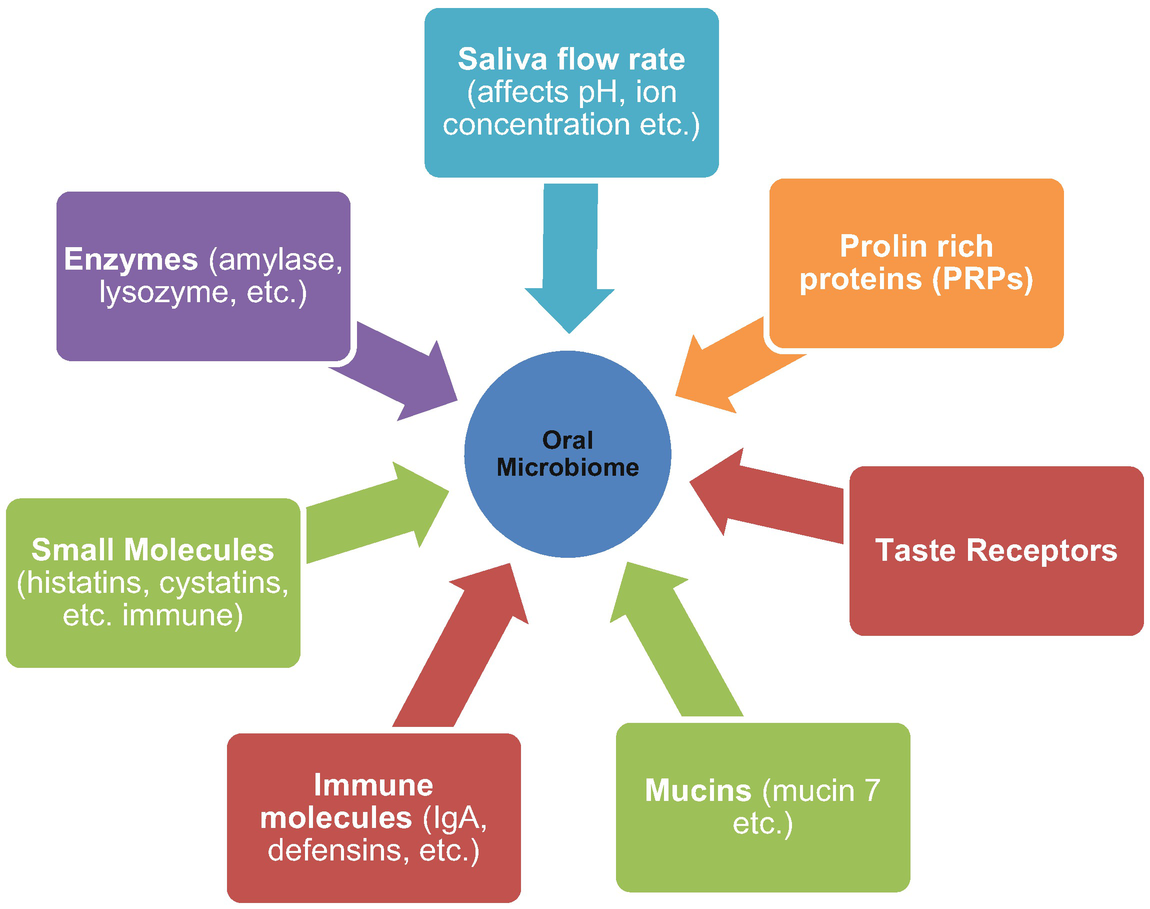

Genetics: Gomez et al. (2017) illustrated the importance of host genetics in assessing the dynamics of bacteria on tooth surfaces just beside the gums (supragingival plaque) and beyond the gum line. For both saliva and supragingival plaque microbiomes, the more similar the genomes of individuals, the more similar their microbiome composition—correctly pointing to the function of host genetics. They obtained data on microbiota, caries, and sugar intake for 485 twins aged 5–11 years. By comparing monozygotic (identical; MZ) and dizygotic (fraternal; DZ) twin pair microbiomes, they estimated heritability (h2), which is the difference in the association between MZ and DZ twin pairs, for the comparative prevalence of bacterial taxa in at least half of their specimens. Of the 91 common bacteria investigated, nearly half show heritability at least 20%. Among these, several taxa’s heritage estimates are relatively small, including Prevotella pallens (h2 = 0.65), a Veillonella genus (h2 = 0.60), and Corynebacterium durum (h2 = 0.54), clearly showing the importance of the host genomes to oral occupancy by these microbes. As shown in Fig. 25.1, saliva and epithelial tissues comprise many compounds of known genetic variation. Proline proteins (PRPs) are significant component of saliva, causing bacterial adherence to tooth surfaces. Mucins function as tethering and energy sources for different microbiota. Immune molecules and other biomolecules (histatins, defensins, etc.) control oral microbial composition and inhibit pathogen invasion. Taste receptors make a contribution to food preferences, and certain enzymes catalyze food, like amylase. All these molecular groups generate specific dietary content for oral bacteria. Eventually, the salivary flow rate determines these molecule concentration and electrolytes.

- 8.

Other conditions: In certain oral health-related conditions like diabetes, hypertension, smokers, dental caries, and periodontitis, phylogenetic diversity of oral bacteria is more than in healthy individuals (Takeshita et al. 2016). HMP reported that there were strong associations between whether individuals had been breastfed as an infant, their gender, and their level of education with their community types at several body sites (Anukam and Agbakoba 2017). Galvão-Moreira et al. (2018) studied 46 female and 24 male patients, aged 18–40 years, and counted both groups’ Streptococcus mutans. The study suggested that there was a significant difference for S. mutans levels in both groups.

Colonization of bacteria in different age groups

Age group | General characteristics | Bacterial species |

|---|---|---|

Just after birth | The sterile environment gets colonized. Mostly aerobic bacteria | Streptococcus salivarius commonly with Staphylococcus albus |

Infants (by 6 months) | Anaerobic bacteria start colonizing | Veillonella species, Fusobacteria |

Tooth eruption stage/Early childhood | They form biofilms over a hard surface | Streptococcus mutans; Streptococcus sanguis |

Adolescence to adulthood | Anaerobes increase more | Increased Bacteroides and Spirochaetes |

Edentulous mouth | Few Bacteroides and Spirochaetes but more of yeast | Streptococcus sanguis and Streptococcus mutans disappear |

Dentures and another prosthesis | Bacteria that attach to hard surface again reappears |

Host secreted biomolecules that can affect oral microbiome heritability (Source: Davenport (2017))

Streptococcus dominant type

Prevotella dominant type

Neisseria, Haemophilus/Porphyromonas dominant type

Most of the studies reveal that oral microbiome constitutes Streptococcus, as dominant bacterial species along with Prevotella, Veillonella, Neisseria, Haemophilus, Rothia, Porphyromonas, and Granulicatella species (Bik et al. 2010) in considerable amount in most of the cases. Although bacterial community remains conserved in most of the individuals, the difference in genus dominance is often there. Even among genera, species differ between individuals. Thus each person’s mouth harbors a unique community of bacterial species but more similar at the level of genus (Bik et al. 2010). Saliva samples from different geographic regions presented with a global pattern of diversity in the human oral microbiome. Diversity among individual from the same location was nearly the same as among different locations (Nasidze et al. 2009a).

25.2.3 Oral Microbiome Sequencing Techniques

Given the range of surfaces required for the processing of samples and the abundance of knowledge accessible to scientists and researchers from such tests, the human microbiome is theoretically a very effective forensic analysis tool. Further experiments have also shown that the makeup of the microbiota (taxonomical structures) differ over time (Flores et al. 2014), and the microbial concentrations of the gut and saliva are more stable.

Variety in human microbiome can be defined in many ways. The most recommended practice is the analysis by targeted sequencing of the variable regions of the 16S r RNA gene of the taxonomic distribution of samples. Several online and offline bioinformatics tools/software/databases are available to assemble similar sequences (traditionally 97% 16S rRNA sequence similarities) into groupings, termed Operational Taxonomic Units or OTUs (Schloss et al. 2009; Caporaso et al. 2010; Arumugam et al. 2011). While it is still an imperfect taxonomic classification system, these OTUs lead ideally to species-level classification of microbial taxa (Goebel and Stackebrandt 1994). By comparing known bacterial species, the programs match OTUs to previously analyzed bacterial taxa and measure the distribution of distinct taxa in a given sample. Although these software differ in the specific algorithms and presumptions used, they all exhibit similar outcomes (Gajer et al. 2012).

As sequencing technologies continue to advance and sequencing costs decrease, whole-genome shotgun (WGS) approaches have begun to be used to test human microbiome rather than targeted 16S sequencing. WGS directly targets all gene content in a given microbial environment and is capable of differentiating microbial and taxa species to a greater extent than those of 16S rRNA amplicons (Schloissnig et al. 2012; Franzosa et al. 2015). Nevertheless, the capacity of microbiome WGS to assist in forensic investigations by linking artifacts and environments with individuals was poorly investigated (Zhernakova et al. 2016), and while it indicates considerable potential, it is currently limited as an forensic tool. The 16S rRNA sequences and their related metadata are the most common data and thus more commonly accessible than in meta-studies carried out by Adams et al. (2015) and Sze and Schloss (2016). The expanded size of data increases the statistical power and thus the efficiency of 16S rRNA information as a forensic tool (Sjödin et al. 2013). The Forensics Microbiome Database (FMD) created by a group that connects publicly accessible 16srRNA-derived taxa data or geolocation (http:/www.fmd.jcvi.org) is an example of using meta-samples for forensic analysis.

25.3 Forensic Applications

Recent advances in genetic data generation have fostered significant progress in microbial forensics (or forensic microbiology) through massive parallel sequencing (MPS). Initial uses in the contexts of biocrime, bioterrorism, and epidemiology are now accompanied by (1) the possibility of using microorganisms as additional evidence in criminal proceedings; (2) explaining causes of death (e.g., drowning, toxicology, hospital-acquired infections sudden infant death, and shaken baby syndromes); (3) assisting in the identification of human beings (skin, hair, and body fluid microbiomes); (4) for geographical diversity (soil microbiome); and (5) to estimate postmortem interval (thanatomicrobiome and epinecrotic microbial community). When contrasted with classical microbiological methods, MPS offers a wide range of privileges and alternative potentials. Prior to its application in the forensic context, however, critical efforts must be made to develop consolidated standards and guidelines through the creation of resilient and exhaustive reference databases (Oliveira and Amorim 2018).

25.3.1 Bite Mark

Human identification is the critical factor in the forensic investigation. It is very crucial to correctly identify the victim either dead or living as well as the perpetrator. There are many ways by which identification is being made. In sexual assault cases, one can come across bite marks which can then be used as evidence to identify the perpetrator. Physical and metric analytical methods are generally used to compare the bite marks with that of suspect’s dentition. Saliva sample from bite marks contains oral epithelial cells that can be used to extract DNA and match with that of suspect’s DNA sample, but human DNA can get degraded in due course of time due to the presence of various enzymes in saliva (Spradbery 2010). Saliva also contains oral bacteria which also gets transferred to the skin when the bite is inflicted according to Locard’s principle. Bacteria can sustain harsh conditions like drying, degradation, and putrefaction, and many more because bacterial DNA is generally enclosed by a cell wall and cell membrane which protects the DNA. So bacterial DNA analysis can pave new way for identification.

Oral microbiome differs from skin microbiome. In bite wounds, bacteria are isolated from normal oral flora rather than skin flora. In a study when forearm was inoculated with tongue bacteria, the transferred bacteria were more similar to tongue bacteria than forearm bacteria. Alpha-hemolytic Streptococci are most frequently isolated bacteria from most of the bite wounds. Streptococcus group of bacteria are invariably present in dental plaque as long as the teeth are present in the oral cavity. Bite marks mostly involve teeth marks. So it is possible that this bacterial species might get transferred when the bite has been inflicted. A study by Brown and colleagues from the Department of Oral Biology at the University of Adelaide, South Australia in 1984, had proved that Streptococcus salivarius is the major species in saliva, and the rate of loss of bacteria is 45–50% per hour from the site of infliction. That means loss of recoverable bacteria was less as time passes. Prominent amplicons can be found up to 48 h, not beyond that. Bacterial sample recovered from a dead body is viable for more duration of time, but in living individuals, it may decrease over time due to washing the area of bite or bathing or using antiseptics over that area.

Direct amplification of oral streptococcal DNA samples from bite marks and incisor teeth of an individual who has inflicted the bite through PCR followed by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis has given significant results (DGGE) (Hsu et al. 2012). Arbitrarily primed PCR (AP PCR) can be used to analyze bacterial DNA, and genotypes of bacterial DNA from bite mark and teeth can be compared. Some of the dominant streptococcal genotypes do not change over time. So this method is helpful in cases where suspect tooth sample is not available for a longer period, but a bacterial sample from the bite mark should be kept well preserved (Rahimi et al. 2005). In AP, PCR sampling and culture should be done within 24 h of the bite infliction, but in DGGE, sampling and culture time can be increased more than 24 h but the resolution of the result obtained is less. 16srRNA along with rpoB (RNA polymerase beta subunit) helps in the identification of bacteria to species and subspecies level as many bacterial species contain multiple copies of 16srRNA gene, and the number of copies can vary between the species, and the hypervariable region of rpoB can bring down the level of identification to species and subspecies level. 16srRNA and rpoB1 reveal that Streptococcus is the most commonly detected genus in saliva, and according to rpoB2 gene analysis, Rothia is the most abundant genus. Experiments using this technique demonstrate that samples from all the individuals can be differentiated from each other and no two individuals had the same oral microbial profiles (Rahimi et al. 2005; Leake et al. 2016). RFLP technique is the most straightforward method to find out polymorphism in 16srRNA gene in bacteria and compare bite mark DNA to suspect’s teeth DNA (Spradbery 2010). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) scheme which is used to isolate and differentiate strains of microbial species by observing DNA sequence variations of housekeeping genes has been developed for oral Streptococci (Do et al. 2010). High-throughput sequencing technique is used to sequence 16srRNA, 16s–23s ITS (intergenic spacer), and rpoB gene region of oral streptococcal DNA. Results obtained had proven that Streptococci amplified from bite marks originated from teeth only. rpoB gene gave the most satisfactory results, whereas the discriminatory power of 16srRNA and ITS was less (Kennedy 2011).

A very crucial factor for forensic investigation is the temporal stability of the reference sample which means if the sample is collected and subjected for experiments, it should give the same results. Temporal stability of oral streptococcal DNA has been assessed in various studies. AP PCR, as well as sequencing techniques, revealed that although the oral streptococcal population is dynamic with species number and proportions fluctuating over time, dominant strains are retained for a longer period, and they were able to identify the suspect with the same potential as earlier correctly (Rahimi et al. 2005; Kennedy 2011).

In infected human bites also Streptococcus species is the most abundant with Streptococcus anginosus as dominant group followed by Staphylococcus aureus and Eikenella corrodens as aerobic species and Prevotella, Fusobacterium, and Veillonella as anaerobic species. Even in abscess bite mark wounds, Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species are abundant (Talan et al. 2003).

Thus it is well proven that salivary microflora can be used as a potential tool for identification as bacterial DNA resist degradation more efficiently and can differentiate two individuals along with their lifestyle. Oral flora can even distinguish between twins that means genetics do not have any influence on the oral microbiome. Antibiotics do have a promising effect on the oral microbiome, but it recovers back to pre-antibiotic diversity after a few days of treatment (Leake et al. 2016).

25.3.2 Body Fluid Prediction

Biological evidence in a crime scene usually constitutes various body fluids that too in trace amounts. It is very crucial to identify the type of body fluid to know the nature of the crime. Various presumptive tests are still preferred to identify the body fluids using specific enzymes that are particular for that fluid. The result is obtained as a color change. However, this test may often give false-positive result due to the presence of that enzyme in a small amount in other body fluids. An alpha-amylase enzyme present in saliva is generally used to identify the saliva, but this enzyme is generally present in small amount in other body fluids like urine and semen that can falsely be recognized as saliva. RNA-based assay targeting saliva-specific gene products have been recently introduced for the detection of saliva (Nakanishi et al. 2009).

An alternative method for the detection of body fluids is taxonomic profiling of microbes. This can be possible for fluids rich in microbes such as saliva, vaginal secretion, feces, and menstrual blood while sterile or nearly sterile body fluids such as blood, semen, and tears are difficult to recognize. Sequencing of microbial 16srRNA gene can be done to discriminate saliva collected from the human body or a crime scene (Hanssen et al. 2017). Oral Streptococci such as S. salivarius and S. mutans are only found in saliva and not in semen, urine, skin, or vaginal fluid. In a study, S. salivarius was obtained in all and S. mutans in most of the mock forensic samples cigarette butt, cotton gauze wiped licked skin and aged saliva samples. Neither S. salivarius nor S. mutans can be detected in the saliva of other animals. Hence, oral streptococci are the new marker for detection of saliva (Nakanishi et al. 2009).

25.3.3 Postmortem Interval (PMI) Estimation

One of the most complex microbiomes in the human body is in the oral cavity. This has been shown to be the second most complex microbiome of the body after the gastrointestinal tract. The native microorganisms biodegrade the cadaver upon death. Oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract microbiomes, thereby play a crucial role in biological decomposition of the cadaver. Many studies are reported for the application of different microbial succession for the PMI estimation (Damann et al. 2015; Burcham et al. 2016; Guo et al. 2015; Metcalf 2019; DeBruyn and Hauther 2017; Hyde et al. 2013). It has been well established that skin microbiome can be used to calculate the postmortem interval of the dead body (Aaspõllu et al. 2011). However, a study (Aaspõllu et al. 2011) reported that most variation over decomposition occurred in mouth microbial populations, while group size and composition were most consistent in the rectum. Recently, oral microbes are assessed to calculate the time since death (Adserias-Garriga et al. 2017). Firmicutes and Actinobacteria are the predominant phyla in the fresh stage of the cadaver. This phylum generally includes Lactobacilli, Staphylococcus aureus, Carnobacteria, Veillonella, Streptococcus, Campylobacteria, Micrococcus, Bifidobacteria, Actinomycetes, and Corynebacterium. Tenericutes presence corresponds to bloat stage with Peptostreptococcus and Bacteroides as dominant species in an early stage, and Clostridiale in a later stage. Firmicutes is the predominant phyla in advanced stage being that Firmicutes are different from that of the fresh stage. They are mainly soil representatives. Dry remains mainly habitat by Bacillus and Clostridiale (Adserias-Garriga et al. 2017). Thus, careful analysis of oral microflora can help in estimating accurate time since death of the dead victim.

25.3.3.1 Forensic Microbiome Database

The Forensic Microbiome Database (FMD) is a human microbiome analysis tool which, regardless of a sequencing tool or the sequenced region acquired from various body sites, compares publicly accessible 16s rRNA datasets to metadata in terms of forensic analysis.

Provide an evidence-based tool for the forensic and scientific community, thoroughly documenting the literature and sequences of microbial samples.

Maintain a database of results, meta-data, and related analyzes managed by quality.

Build a website consisting of software that allow users to evaluate their individual data, interpret and quantify the results, and compare the results with the existing data for the public at large.

Machine learning has been used to determine the geographic position from where the sample was collected, using the comparative richness of bacterial taxa in one sample (Edgar 2013; Human and Project 2012). The more detailed and complex the FMD data are, the more precise the forecasts are. Such forecasting could be used to assess the location of a survivor of trafficking in human beings or as evidence in a crime scene to limit a person’s investigation range.

Originally, this research involved the selection and management of samples of human microbiome across five countries worldwide, namely Chile, Barbados, Hong Kong, and two South African sites. Oral and stool samples from healthy women aged 18–26 years have been obtained. Immediately frozen samples were sent to J. Sequencing and subsequent research laboratory of Craig Venter Institute (JCVI).

This also gathers data from databases such as NCBI, EBI, and DDBJ. A quick read (src), which stores raw sequencing for thousands of scientific studies (Fig. 25.1), is held in NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) (Fig. 25.1). Scientists deposit their sequences with the SRA to make their experiments reproductive and use them for new insights through other experiments. In order to identify newly added studies to the database, the FMD regularly checks the SRA. It is of concern to only a certain section of the samples contained in the SRA. These are human-associated studies of the microbiome—sequence of readings of bacterial 16s rRNA on a human body site with appropriate metadata. Using 16s rRNA samples, the relative diversity of the population of microbes in that body site can be determined. SRA samples comprise details on each sample—primarily how it was processed and sequenced.

Within NCBI, the BioProject contains several samples of the same study in an umbrella group. This BioProject explains the analysis and permits users to access all SRA samples. To query databases in order to locate these studies, search words such as “human microbiome 16S” are used. If a sample is found that fulfills the specifications mentioned above, other conditions need to be met, since the intended FMD feature must be further analyzed. Metadata linked with a report must at least include the geographic location of the collection sample and the reported document detailing the report (in the city level). Test inclusion does not allow other details such as the age and gender of the human host to be useful and preserved in the database. Most of the metadata is obtained from the website where the study has been downloaded, but also from other sources such as the manuscripts released. Actually, the public database and its associated research methods contain only safe human samples, but unhealthy specimens are still collected for potential inclusion.

Samples of other sequence databases such as EBI and MG-RAST with a similar organizational structure are obtained in addition to NCBI.

25.3.3.2 The Data Analysis and Interpretation Process

Looking at the taxonomic distribution of individual samples from the collected publicly available 16S rRNA sequence data.

Comparing the taxonomic distribution of multiple samples from the collected publicly available 16S rRNA sequence data.

Comparing a user-supplied sample with all the publicly available 16S rRNA sequence data and geolocating it through the closest matching taxonomic distributions.

For more information about the 16S rRNA sequence data used in the FMD, one can refer to the statistics page.

25.3.3.3 Where Does This Data Come from?

The FMD collates the accessible 16S rRNA sequence data. Oral and stool samples from healthy women were obtained and analyzed in cooperation with the co-regional investigators of different locations around the world (Hong Kong, Barbados, Chile and two sites in South Africa). Sequence data are also extracted and evaluated from public websites. All FMD sequence data were obtained from different body sites of samples of healthy adults (≥18 years). On the data statistics page, a comprehensive list of available data like tests, counts, and metadata is maintained and updated regularly.

25.3.3.4 How Was the Data Analyzed?

For each sequence, the FMD pre-calculates the taxonomic population distribution from the public dataset using the UPARSE pipeline (Edgar 2013) and then maps these populations to their geographic position (discreetly, not continuously) using machine learning strategies to classify bacterial taxa (at different taxonomic levels) that better differentiate across different geographic locations. These two measures are outlined in the manual tab available on the FMD website.

25.3.3.5 What Data Should I Upload into the Database?

In addition, the FMD will take 16S rRNA sequence data in FASTQ format (see SOP on website). The website will currently use user-supplied Mothur formatted taxonomy and OTU files as inputs to display the taxonomic structure of the data, equate it with current FMD data, and estimate the geographic origin of the data via the FMD analysis tab.

25.3.3.6 Why Does the FMD Pipeline Use UPARSE, and Not Mothur or Qiime?

Various programs will predict a 16S sample taxonomic structure, like Mothur and Qiime. Because UPARSE utilizes Mothur throughout the taxonomic assignment phase, the software differ except during OTU construction. UPARSE was shown to be faster during benchmarking with less OTUs (Edgar 2013). This is largely attributed to the elimination of singletons by UPARSE (a singleton is a read with a sequence existing entirely once, i.e., is specific among reads) before OTU clustering (or OTU generation). Removing singletons eliminates sequencing errors. Moreover, UPARSE is an agnostic sequencing tool, allowing it impartial to interpret sequence datasets generated separately (i.e., 454 or Illumina). The manual on the website includes a comprehensive explanation of the UPARSE system.

25.3.3.7 What Metadata Is Available on the FMD?

The database includes metadata such as body location, topic age and gender, and geographical details such as region, district (i.e., state or department or province), and area. In certain applications, these parameters are undefined and called “NA.” More and more details of the FMD is filled with, the more reliable would be the geolocation predictions.

25.3.4 Human Identification, Ethnicity Prediction, and Geographic Location Determination

Community composition within the human microbiome varies across individuals, but it remains unknown if this variation is sufficient to uniquely identify individuals within large populations or stable enough to identify them over time (Franzosa et al. 2015).

25.3.4.1 Identity

Recent large-scale human microbiome studies have shown considerable variation in body-site-specific community composition and bacterial organism activity among healthy individuals (Human and Project 2012; Qin et al. 2010; Cao et al. 2018). Furthermore, it was shown that human microbiome characteristics may be optimally correlated with individual people over significant phases of time (Schloissnig et al. 2012; Fierer et al. 2010; Poethig et al. 2013). Such findings indicate a special and secure distinction within a population dependent on their native microbiota. There has, however, been no systematic attempt to experimentally assess the viability of microbiome-based detection. To do so, it involves proving (1) that an individual-specific “metagenomic code” can be found in a population sample; (2) that perhaps the code can be strongly redetected at a later stage; (3) that the code is impossible to fit an unknown sample incorrectly; and (4) that such codes can be built for a significant fraction of individuals. Such criteria stress the nature of human microbiome identity with microbiome formation, composition, personalization, and transient stability—foundational topics in microbiome science ecological approaches (Franzosa et al. 2015).

In 2014, proof of concept was documented to distinguish two persons using oral micrbiome (Sarah 2014). Tests from individual and combination studies revealed that samples can be clustered from one individual and isolated from samples from a second individual (Leake et al. 2016). It had shown that salivary microflora displays substantial heterogeneity, and using a PCR-based metagenomic method using the two gene targets, respectively, 16s rRNA gene and rpoB2, it was possible to discriminate between two different individuals. In this analysis, a 58 genera central microbiome was postulated by integrating three targets. This high number of genera comprises about 95% of each individual population, suggesting that most variations come from species/strain level. Results showed that with this type of testing, the minimum number of sequences is 100,000 as this provided an excellent distinction between individuals with all targets.

Recently Neckovic et al. (2020) defined how well a distinguishable microbiome could be passed to another person and substrates, and vice versa. The findings of this pilot study introduce a variety of potential challenges for the use of microbiome sampling for forensic purposes; without the existence of comparison samples from an individual(s) obtained from the correct body location, with a detailed history of all individuals or artifacts closely touching the skin/body site within a currently undefined timeline, it would be different.

25.3.4.2 Geolocation

This high heterogeneity in the human salivary microbiota is not geographically organized. Although there is considerably more variation in bacterial genera relative to different people than from the same population, variability between persons from the same region is about the same as variation between individuals from different places. Generally, the interpopulation portion of the variance in the distribution of the bacterial genera is 13.5%, which means that each organism comprises on average 86.5% of the overall variance found when all organisms are collected. This is strikingly proportionate to the amount of interpopulation variability usually found among humans for neutral genetic markers (Romualdi et al. 2002; Li et al. 2007). Thus, in this context, genera distribution of individuals acts as a neutral genetic marker if one equates individual bacterial composition with the genetic composition of human populations (Nasidze et al. 2009a, b).

25.3.4.3 Ethnicity

Mason et al. (2013) found that the subgingival microbial fingerprint can successfully discriminate between the four ethnicities. To do this, a Random Forest machine-learning classifier was trained to develop an educated classification algorithm using subgingival microbial signatures, which was then applied to a test dataset to examine the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of the prediction. The subgingival microbial community was able to predict an individual’s ethnicity with a 62% accuracy, 58% sensitivity, and 86% specificity.

25.4 Concluding Remarks

The human microbiota contains fungi, bacteria, and viruses, which live in and around the body. As evidence-based tool for the correlation or exclusion of people of concern linked to illegal activity, microbiomes have intangible value in forensics. Work has shown that the microbiome is isolated and specific signatures from textures such as tablets, shoes, and textiles can be retrieved. In order to explore the effectiveness and possible shortcomings of the micronutrient profiling, further research is necessary before the human microbiome in general and salivary microbiome in particular are used as a research tool. This involves the detection range, risks involved with, or the application of microbial profiling for forensic applications, of microbial transfers among humans or objects.