MANIACAL MELODY

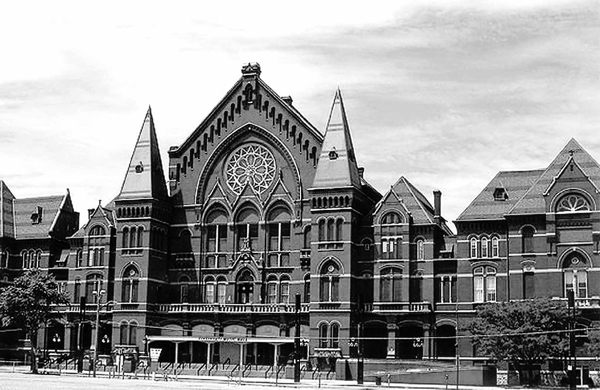

One of Cincinnati’s most iconic buildings rises majestically above Elm Street, keeping watch over the city since the time when streetcars and canalboats passed through its shadows. The grand Victorian Gothic structure stands as a visual testament to the city’s golden era; however, it is what lies beneath Music Hall that gives the building’s façade a more mysterious and sinister appearance. To understand what haunts Music Hall, you must travel to the intersection of Twelfth Street and Central Avenue. This quiet and unassuming area on the northeast corner of the intersection holds an ominous connection to the city’s past. Here stood the first public hospital in the United States. What patients experienced here, by today’s standards, would be considered malpractice and torture.

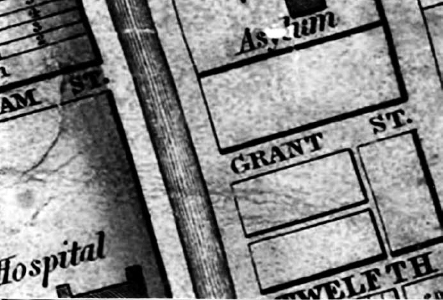

In 1795, the population of Cincinnati was only five hundred. By 1820, the number had reached nearly ten thousand. The streets were overrun with the homeless and the mentally ill. Cincinnati Township was quickly finding out that its informal approach to disease and the welfare of its citizens was not suitable. On January 21, 1821, an act was passed in the legislature establishing a Commercial Hospital and Lunatic Asylum for the State of Ohio. The area was to be no less than four acres and located within one mile of the public landing on the Ohio River. The state donated $10,000 in depreciated bank bills to the project, of which only $3,500 was realized in actual funds. The act establishing the commercial hospital proclaimed that the trustees of Cincinnati Township were to provide the “safe keeping, comfort, and medical treatment of such idiots, lunatics, and insane persons of this state as might be brought to it for these purposes.”

The “Commercial” in the hospital’s name required the trustees to admit and care for, without charge, all boatmen belonging to boats owned by citizens of Ohio and all boatmen who were citizens of states that provided reciprocal care to boatmen of Ohio. The Miami Canal ran just outside of the hospital and behind the land that would later be home to Music Hall. Additionally, the trustees were required to receive and care for all paupers of Cincinnati Township free of charge. Costs were paid by the state, county or family depending on economic status and place of residence. All others were charged two dollars per week for board and medical treatment.

Daniel Drake, who founded the Ohio Medical College, is often credited with turning the idea of the hospital to reality. Drake himself drew the plans for the original building and was paid ten dollars by the township for this service. The Commercial Hospital and Lunatic Asylum operated in connection with the Ohio Medical College, and Drake used the facility as an opportunity to afford experience to his students. The faculty of the college would render free services to patients, and in return they were given access to the hospital for the purpose of observation of the treatment of diseases and surgical procedures.

Within months of opening its doors, the building was serving as a general hospital, insane asylum, orphan home, almshouse, medical college and distribution point for relief efforts. It was a three-story building with the first floor being cells for men, the second floor having accommodations for women and third floor holding a lecture hall for students. The hospital was completed in 1823 and had four floors, including a basement. The lunatic department was completed as a separate building in 1827. After subsequent additions in 1833, the hospital totaled 150 beds, with a maximum capacity of 250 patients.

Soon after opening its doors to the public, the hospital began to garner a bad reputation. By all accounts, the conditions were appalling. Visitors would become physically ill from the stench of filth, human waste and death. The lunatic department was especially unforgiving. Patients deemed mentally ill or otherwise not of sound mind were chained to the floor, where they would wail and scream day and night. There were so many deaths here that the superintendent was nicknamed “Absalom Death.”

The hospital was a permanent home for many of the patients. There was no privacy. Patients of the facility experienced nothing less than a chamber of horror. Many treatments of the time are seen today as bizarre and sadistic rituals of torture. The practice of bloodletting was believed to treat many illnesses by purifying the blood. Doctors would drain blood from the arms, neck, temples or wrists. Primitive devices and leeches would be used to spill large amounts of blood, and sessions would usually stop only when the patient lost consciousness. It wasn’t uncommon to have one patient emptied of hundreds of ounces of blood over several dozen sessions. The practice was often an intense battle, with patients having to be subdued and restrained as blood was spilled and thrown in all directions.

Commercial Hospital and Lunatic Asylum. Courtesy Don Prout.

The sealed windows of the hospital held in the stench of human waste from overflowing chamber pots. The severe lack of physical activity caused chronic constipation in patients. In some cases, if a patient became uncontrollable, laxatives were given to create a calming effect by means of distraction. Other treatments included short periods of starvation, enemas, induced vomiting and extremely hot or cold baths. Some patients faced the tranquilizer chair and were held immobile in a sitting position for hours to lower their pulse and blood pressure. Others were placed on boards spinning at great speeds with their heads facing out, so as to force blood into the brain. Tranquilizers and narcotics such as morphine, various tonics, wine, ether, molasses and sassafras oil were used as patient control methods. Some accounts state that poison hemlock would be used on especially difficult patients, which would leave them temporarily paralyzed for days. When substances were either unavailable or insufficient, the staff would resort to forceful restraint or in some instances outright abuse in the name of treatment.

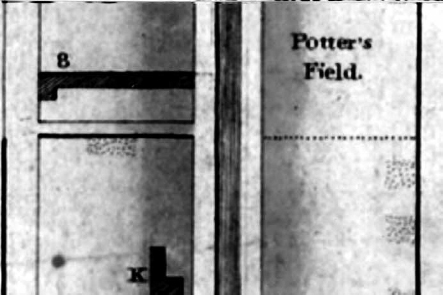

The hospital was responsible for taking in the city’s poor and unwanted, and it was also responsible for their proper disposal when death came for them. Cincinnati Township appointed a plot of land as a potter’s field to bury the city’s poor, indigent, suicides and unknowns that is located under present-day Music Hall. Once the life of these souls ended, they were thrown into the ground like so many pieces of trash. Well-to-do citizens of Cincinnati Township did not afford them even the simplest luxury of a wooden box. Their bruised, battered and scarred bodies were simply dumped into the potter’s field. No one knows just how deeply permeated the soil is with the forgotten bodies of the insane. Today the ground is soured with thousands of corpses forgotten by history and time. Those lost souls who disappeared from society still haunt the area today.

In the fall of 1832, Cincinnati was stricken with a cholera epidemic that would leave hundreds dead. The canal system was a source of commerce for the city, but it also brought disease. The stagnant water in the canal was the perfect breeding ground for cholera. Canal workers regularly died of the disease. Those stricken with cholera would suffer from extreme bouts of vomiting, diarrhea and cramps. Many children became orphans because of the epidemic. As a result, an orphan asylum was constructed on what is now the site of Music Hall, near the potter’s field. By 1837, the Commercial Hospital was at capacity and began sending patients with infectious diseases to the orphan asylum. The orphanage then became known as the “Pest House.” The city’s resources were strained, and more tragedy was yet to come.

The year 1849 was especially tough for Cincinnatians. Another more serious cholera outbreak occurred. Many people died of dehydration only hours after showing the first symptoms. The treatment was nearly as torturous as the disease itself. Doctors prescribed calomel, a form of mercury chloride, for the treatment of cholera. Patients who were treated with this dangerous chemical would routinely lose their hair and teeth. Many patients died of mercury poisoning during treatment. Citizens fled to the community of Mount Pleasant to escape the grip of the deadly disease. After the epidemic had ended, residents changed the name of the community to Mount Healthy in honor of their good fortune. By the end of the 1849 cholera outbreak, over eight thousand Cincinnatians had succumbed to the disease. The ground used for the potter’s field swelled with bodies.

Maps showing the Orphan Asylum and later the potter’s field. Courtesy Doolittle and Munson.

The German population of the city held their Saengerfest, a choral festival, over the area of the potter’s field as early as 1867. A tin-roofed wooden structure was erected by the Saengerbund Singing Society, at which time human skeletal remains were unearthed. Stories of transparent beings walking the land soon followed. One year, heavy rain pelted the tin roof loudly and relentlessly during the festivities, causing delays in the music. Reuben Springer, a prominent citizen, contributed a $125,000 challenge grant with private funds for the construction of Music Hall in what is believed to be the nation’s first matching grant fund drive.

Once the plans were put into action to build Music Hall, the exhumation of countless bodies began. Many large dry goods boxes were found to be filled with scattered and mixed bones and broken and crushed skulls. Not a single full skeleton was found. Crowds began forming at the site, and without security guards there was no way to protect the site from theft. Skulls were prodded with fingers poking into empty eye sockets. Medical students stole bones and skulls during the night. The souls who finally found peace away from the confinement of the hospital were once again dishonored. Many bones were disinterred during the period from 1876 to 1879 and were relocated to Spring Grove Cemetery.

The original structure took only one year to complete, opening just before the May Festival in 1878. The wings of Art Hall and Exposition Hall were then added. With nearly four million red pressed bricks, the magnificent gem of the city was completed at a cost of $446,000. During renovations in 1927, seventy more grave sites were disturbed. The bones were carefully placed in a four-foot vault and lowered beneath the base of the elevator shaft, where they lay forgotten for over sixty years. During renovations in 1988, more than two hundred pounds of human bones were unearthed, including those from men, women and children. The harsh injustices enacted upon these people are hard to comprehend. Do the insane and mentally ill from another era still roam the area looking for help that they could never find in life? Many ghostly occurrences take place in and around Music Hall, from the lighthearted to the disturbing.

During performances, some patrons have reported seeing people in nineteenth-century clothing mingling in the crowds, only to disappear. Doors open and close by themselves, and escalators are turned on by an unseen force after they have been turned off for the night. Ghostly footsteps can be heard throughout the building when nobody is there. The sounds of laughter and talking are heard by night watchmen. Perhaps they are ghosts of a time gone by who are forever linked to this place. Some of the occupants are not as happy to be there. Night guards have reported angry whispers filling the elevator late at night. Perhaps they are justly upset with the impudence of those who have stomped atop the hallowed ground for nearly two hundred years. Guards have heard the sound of bodies hitting the floor as if invisible inhabitants are jumping from the balconies. They hear the ghostly sounds of a music box playing near the elevator late in the evening after all others have gone, perhaps from the orphanage era. A beautiful, otherworldly singing voice has been heard throughout the building, and apparitions have been seen dancing in the ballroom. Staff members have reported that while opening the building in the morning, they have heard someone practicing the piano in the symphony hall, only to find that nobody of this world was there. While locking up for the evening, one employee walked into the ballroom and discovered that it was filled with people dancing in nineteenth-century dress. He was unaware of any event being held there that day. He contacted his superior to inquire about the party and was informed that they had no reservations for the room. The employee went back upstairs to sort the matter out and found the room to be dark and empty. Outside the building, cameras have captured orbs and full-bodied apparitions walking the grounds. There is no lack of ghostly presence at this site. It is unknown how many spirits are still lost in these symphonic corridors. While visiting here we have captured numerous orbs, shadow people and apparitions on film.

The foyer inside Music Hall. Courtesy John Wright.

Music Hall is still a masterpiece after 130 years. Courtesy Wholtone.

Whether haunted by a dark history or by time itself, Music Hall holds more than 130 years of forgotten secrets within its walls. The weary souls are eternally bound to a dark and unforgiving solitude. The ghosts that haunt here have found freedom from confinement—only in death. The cries of the maniacal are swallowed up and replaced by the joyful sounds of string instruments. They lived a desperate life filled with tears and loneliness, only to die and be disposed of without dignity. They still roam Music Hall looking for the help that they so desperately needed in life. The building now stands tall as a magnificent grave marker for all those who have been lost, with hopes that the dead may no longer be disturbed.

HAUNTING ACTIVITY SCALE

Frequency***

Intensity***

Type: shadow people, apparition, poltergeist, bleed-through, residual imprint