Conceptualizing Neonatal Development

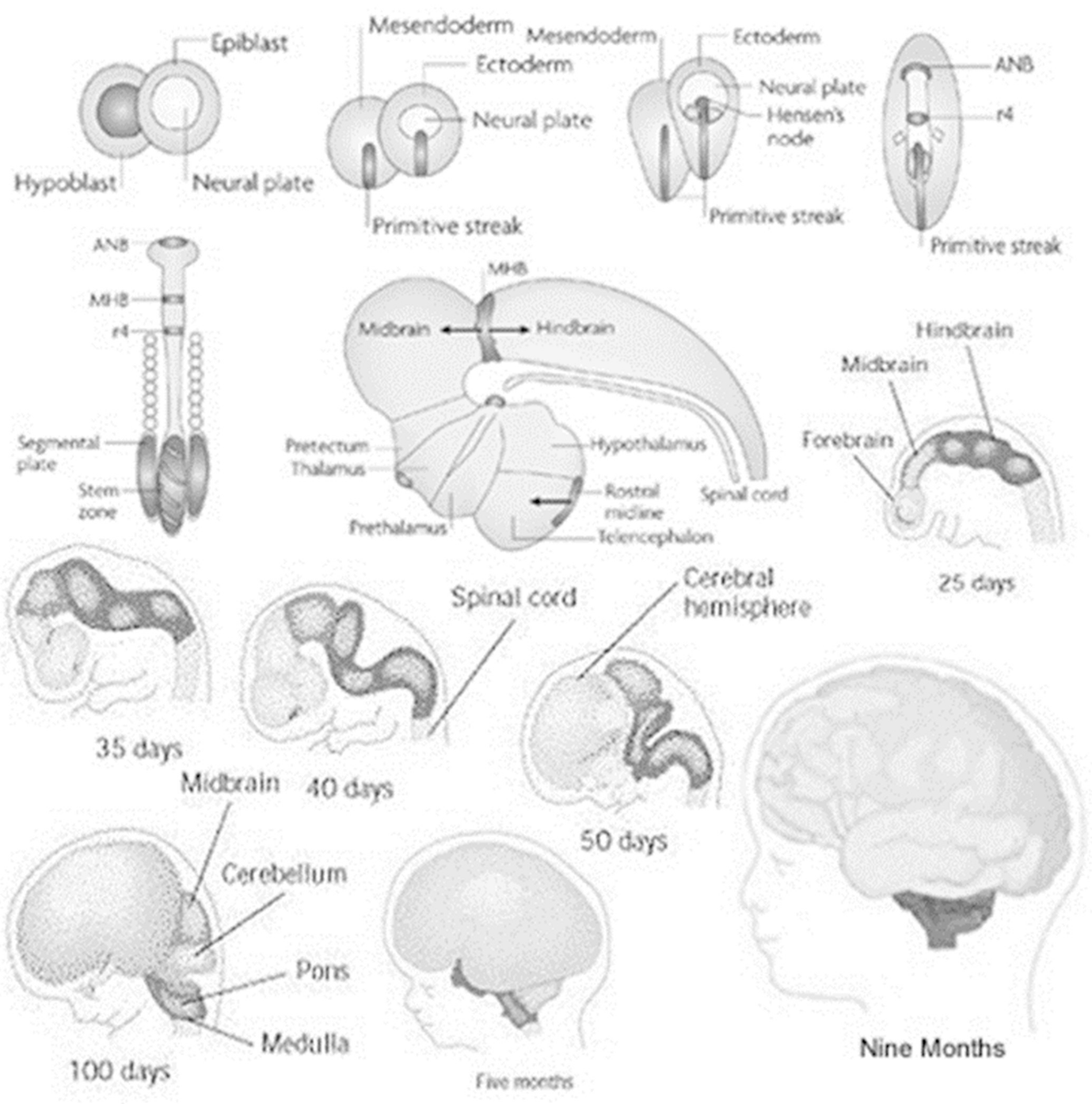

Concept analysis is essential in the creation of theory [1]. By defining terms or concepts, within the context of the theory presented, clarity and understanding can be assured. For providers caring for neonates (infants up to 28 days of life) in neonatal intensive care (NICU), development serves as the core of the care decisions made every day [2]. Developmental psychology recognized the ability for the brain to adapt to varying circumstances many years ago, but its application to practice continues to evolve, examining development, scientifically, over the lifespan with a large number of theories focusing on childhood; the time when the largest amount of change occurs. For the neonatal population, Newman et al. report that early, specifically fetal and neonatal, development markedly affects mental health in later life [3].

Fetal brain structure development with approximate gestational landmarks. (Reproduced with permission. Source: researchgate.net/publication/327222314)

Through the study of those born too soon, we can explain and compare this vulnerable period for any infant. Als, through her work designated as synactive theory, developed a program for assessment and care known as the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP®) after demonstrating a reduction of neurodevelopmental disabilities [7, 8, 9]. Bingham conveys the benefits of this specialized care decreased length-of-stay, improved nipple feeding transitions, and improved family interactions. Als furthered her research with an additional study of her program’s ability to improve brain function and structure in preterm infants. Correcting the effects of intrauterine growth restriction, a known comorbidity of neonatal neurodevelopmental issues, by hypothesizing the reduction of noxious stimuli resets the physiologic responses to pain and stress, thereby reducing the release of damaging free radicals which cause toxic damage resulting in inappropriate cell death along with changes in sensory thresholds, activity, and sensitivity.

Haumont examined the effects of developmentally supportive care by measuring cerebral hemodynamics with near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) and noted significant variations during a routine diaper change. Even a procedure not typically viewed as painful, like a routine diaper change, had an impact [9]. Ackerman’s work studying the developing brain examined the influences of norepinephrine and serotonin and the roles; these endogenous chemicals play in the perception of pain and the physiological responses to it [10]. If even changing a diaper can be viewed by a newborn, in this case a premature one, as affecting cerebral hemodynamics similar to a procedure known to cause pain [9], does it not stand to reason that a noxious exposure could contribute to at least an equal disturbance? A developing fetus, within the womb, is very much like the preterm infant except that we are afforded the ability to study the reactions of an infant whose physiology is expected to function before it would be if carried to term. Noting that habituation, through exposure and chemically mediated responses, can play a large part in the modeling of the brain during development; Ackerman’s preliminary conclusions are now being studied in much greater detail.

Perinatal Exposure to Cannabinoids Through Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

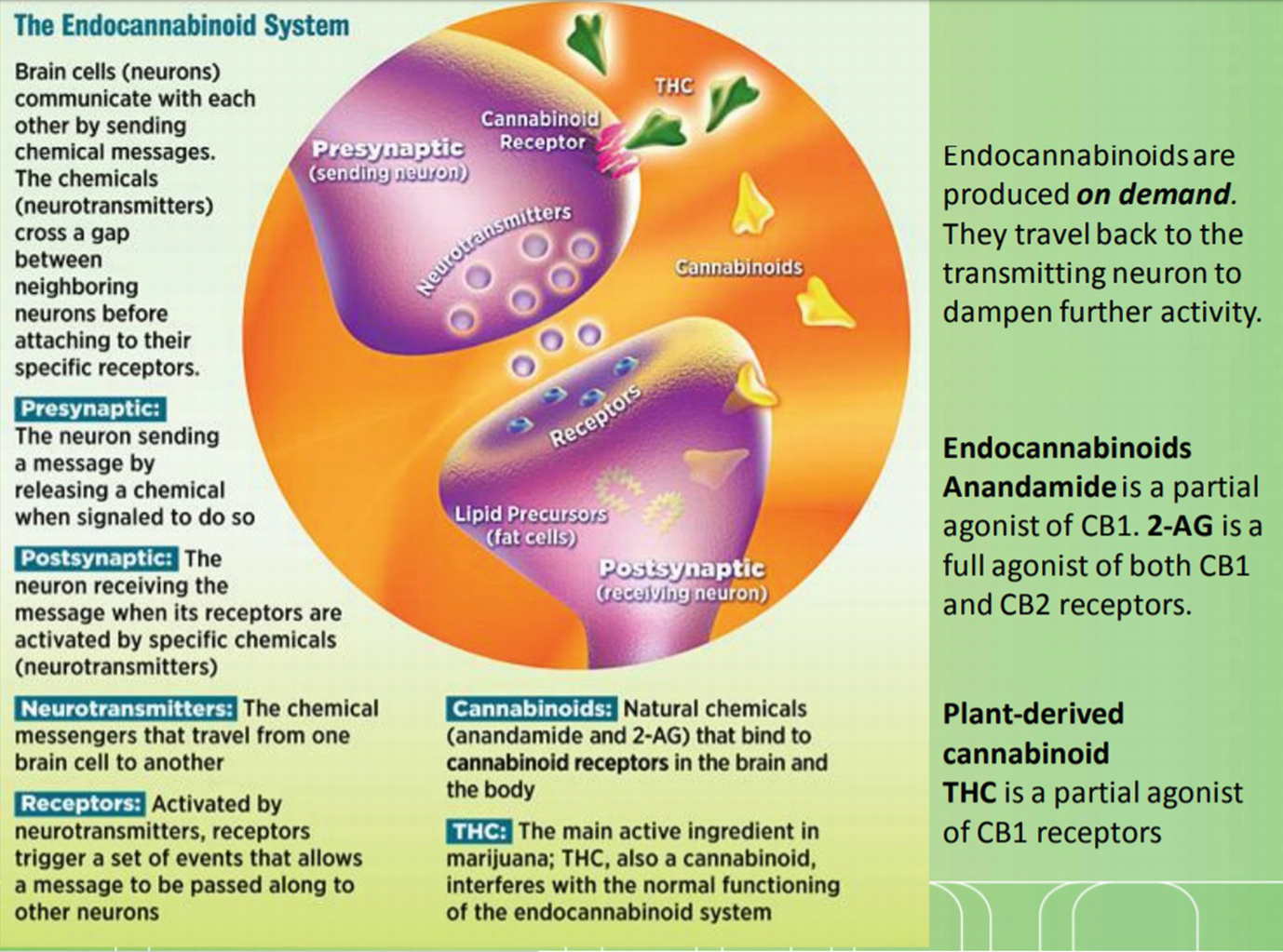

Endocannabinoid system. (Reproduced with permission. Source: March of Dimes)

All women should be asked about alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use, including marijuana and other medications used for nonmedical reasons, before and in early pregnancy.

Women reporting marijuana use should be educated about the potential adverse consequences of use during pregnancy.

Women who are pregnant or considering pregnancy should be encouraged to discontinue marijuana use.

Pregnant women should be encouraged to discontinue marijuana use for medicinal purposes in favor of alternative therapies with pregnancy-specific safety data.

There are insufficient data to evaluate infant safety during lactation and breastfeeding, and, in the absence of this data, marijuana use is discouraged.

Since THC is lipophilic, understanding that breastmilk contains increasing concentrations of fat during each feeding/pumping session, then its presence in breastmilk is certain. What is not certain are the absolute transmission concentrations as they appear both dose (amount of maternal use) and proximity (to sampling) dependent. Historically, the evidence for documenting has been old and limited, but the presumption for proximity to maternal use and dosing should be relatively self-evident and is now emerging in the literature.

Because marijuana is still federally regulated as a schedule I controlled substance, effective trials to study THC concentrations in breastmilk have historically been severely limited. More recent trials are measuring the transmission of THC in mother’s milk, and some have even detected the cannabidiol found in CBD oils purportedly not containing anything transmissible. Even if the transmission levels are studied and documented, how will safety be assured? Marijuana, whether medical or recreational, has not been subjected to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) efficacy testing and approval with safety monitoring. It is also not subject to stringent prescribing guidelines, with some states only permitting usage recommendations, and supply chain safety of other currently scheduled drugs [12]. And let us not forget the cannabidiol (CBD) being marketed as safe for all because it contains no THC, or does it? Without regulation, consumers may be exposing themselves and their children to levels that may be “acceptable” to the industry but far from zero.

Developmental Impact for the Newborn Period and beyond

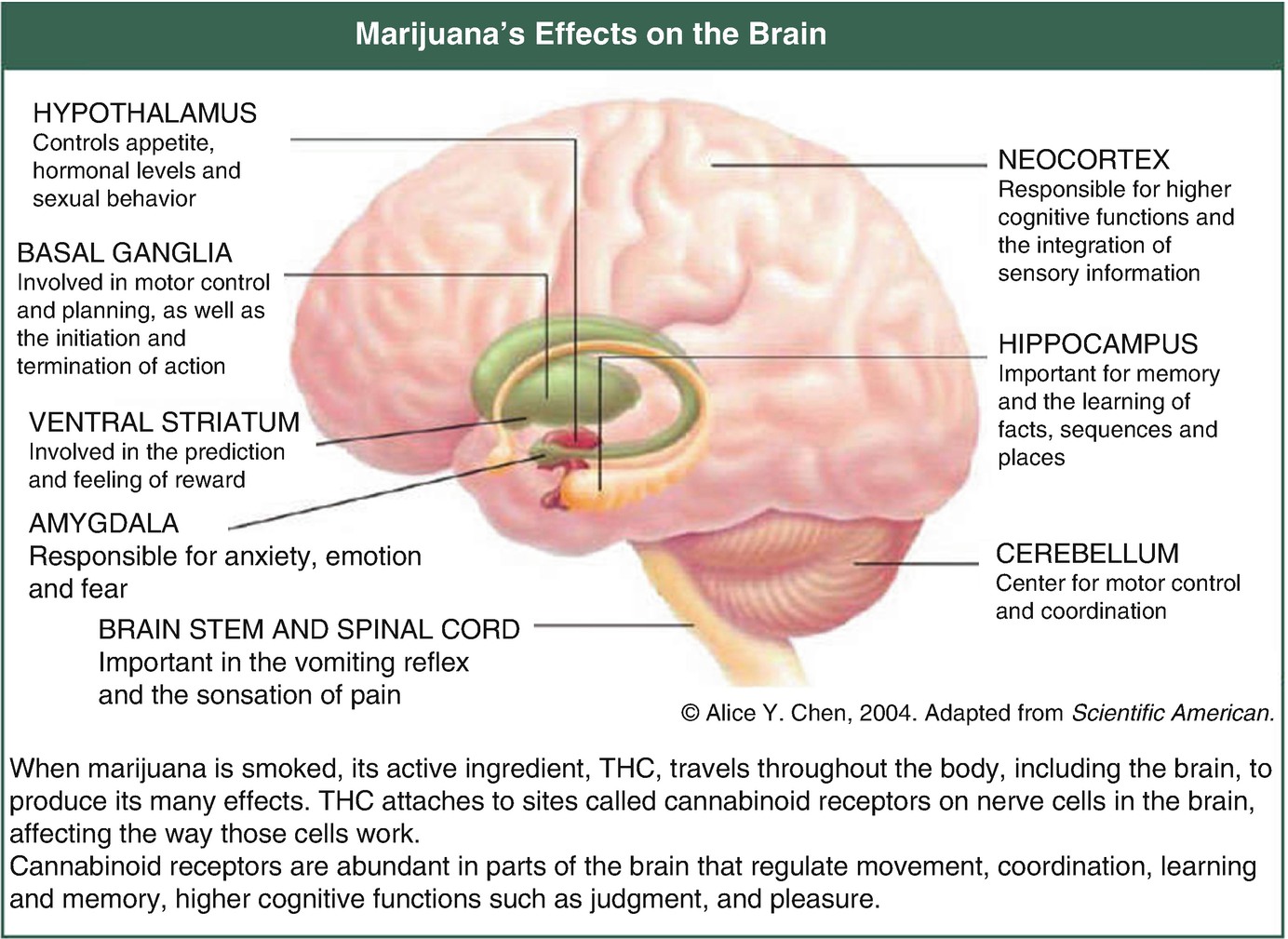

Marijuana’s effects on the brain. (Reproduced with permission. Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse www.drugabuse.gov)

Outside the womb, babies are further exposed through breastmilk if mothers continue to use marijuana following delivery. Historically data was limited and antiquated with relatively little information on THC concentrations available. But, more is emerging that demonstrates THC is passed into the milk of mothers who use marijuana [13, 14]. Δ9 tetrahydrocannabinol, not metabolites, are found in varying concentrations in maternal milk. Levels found vary based on the amount and route of consumption as well as timing of sample collection. Keeping in mind the lipophilic nature of THC, it can be found in maternal milk for several weeks after last use if the mother is a chronic user. To a lesser extent, cannabidiol (CBD) has also been found in detectable levels in maternal milk [15].

The emergence of epigenetics has presented us with an even more detailed examination of the physiologic properties associated with development, specifically the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Many studies have been published and reviewed to present the data alluding to the connections between various exposures during the perinatal and neonatal periods and the impact they have on later life. Montenegro et al. discussed the importance of understanding this relationship in their 2019 systematic review of the literature. They discussed Roseboom’s 2001 landmark work that detailed the observations of mortality in adults who had been exposed to the Amsterdam famine in the mid-1940s during their fetal period [16]. Whether DNA methylation, noncoding RNAs, or histone modifications, the associations with disease many years after exposure are continuing to emerge [3].

The exact mechanisms for this development are very complicated, involving both genetic and environmental factors, and its study continues to evolve [17]. Improving upon the epidemiological theories from the 1950s with the fetus being characterized the fetus as a “perfect parasite,” Dr. David Barker theorized that in utero programming was the major contributor leading to future disease issues in his fetal origins hypothesis. Although birthweight was found to be the most commonly available and easily compared measure of fetal well-being, it was found not to be as entirely sensitive as initially proposed [18]. Developmental experts have further added environmental exposures to the list of factors impacting later life [7, 8, 9]. Interestingly, it has been concluded, the most vulnerable period for this remodeling is in the first 3 months of development. A period correlating directly with either the time before pregnancy awareness or the time when women are most vulnerable to seeking marijuana as an alternative to combat the effects of nausea and vomiting associated with the first trimester of pregnancy [12].

Numerous studies coinciding with the medical and recreational legalization of marijuana have examined the still-developing adolescent brain. The National Institutes of Health is currently following approximately 10,000 children ages 9–10 into adulthood to facilitate understanding the many factors that can disrupt development with the ABCD study [19]. In October 2019, Frau et al. published data linking prenatal cannabis exposure in rat dams to long-term synaptic plasticity changes in dopaminergic neurons in male, but not female, offspring. These changes were displayed as altered balance in excitatory and inhibitory neuronal stimulation which led to amplified preadolescent THC exposure sensitivity [20]. Duke University scientists also found a sex-based difference in DNA methylation in human brain tissues with males having more alteration and exhibiting more neurobehavioral symptoms through the gene’s known link to autism [21]. Their study examined hypomethylation in the sperm of THC exposed male rats which was also detected in the forebrains of the offspring. By studying various aspects of pharmacokinetics, structural and psychological impacts, and global function, they all reach similar conclusions—marijuana affects brain cells. Even the adult studies examining cortical thinning, owing to continued pruning, are demonstrating the impact the drug has on existing, fully-developed neurons [4].

Impact of Legalization on Use in Pregnancy

As the legalization of both medical and recreational marijuana use has moved across the country, the medical community is dealing with the far-reaching implications. In the state of Colorado, for example, where marijuana was legalized for medical use in 2001 and recreational use in 2014, marijuana usage among pregnant women has risen dramatically [22]. Additionally, the potency of available products has also risen in recent years, further raising the concerns for exposure to the developing fetus and neonate. In the 1970s, the THC potency available in most marijuana was around 2%. With advanced cloning techniques, the concentration is currently consistently found at 20–25% [23]. The rise of edibles and vaping has introduced entirely new compounds and concentrates, known by a variety of names based upon the extraction techniques used. Processing concentrates, known as budder, kief, or shatter/scatter, can have concentrations of 40–80% THC, with some even approaching 100%. Users are “accenting” their typical smoking method with the addition of one of these concentrates, known as “topping your flower,” and is only one of several ways to markedly increase the THC concentrations they are consuming. If the user is a pregnant or breastfeeding woman, their child is also exposed to much more THC. As states begin to legalize both medical and recreational marijuana, more data will become available. Sadly, it will only be available after the damage has been done.

Drs. Reece and Hulse have reviewed the implications for prenatal cannabis exposure from three major cohort studies. These studies, with a notable agreement, detailed impaired brain growth, intellectual deficits, as demonstrated on school tests, as well as cardiovascular anomalies, in addition to others. The effects of cannabis exposure were suggestive of a dysfunction spectrum ranging from mild or moderate to very severe [24]. In another study, they directly linked rising autism rates to both the increasing use and concentrations of cannabinoids in the United States and Australia, citing several very large studies and data compiled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [25]. By comparing data regarding cannabinoid concentrations from federal seizures and CDC data on autism rates, they were able to demonstrate a potential causality, using Hill criteria, across the United States linked directly with what they termed high-use states and legalization in those states. In high-use states like Colorado, Alaska, and Washington, rates of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) were rising faster than low-use states at rates reaching statistical significance. Although not experimental studies, which would be ethically unfeasible, these are the first to detail true teratogenic implications with marijuana exposure. Historically reports were limited to in utero growth restriction and lower birthweights as these were the only data available for comparison and noted previously. Newer information, however, is also demonstrating lower postnatal growth rates and increased morbidity [25, 26]. Even the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a statement in October 2019 strongly advising against using cannabis in any form, including CBD, while pregnant or breastfeeding [27].

Despite all the emerging, and largely very concerning information for safety and developmental impacts, Colorado lawmakers advanced and signed into law, on World Autism Day 2019, House Bill 1028, which adds autism to the list of approved conditions for the use of medical marijuana. Although the legislation had been proposed and passed by the assembly in two previous sessions, it had been vetoed by the previous administration, citing a lack of evidence to support its use, especially for children. To date, the FDA has only approved one form (Epidiolex—cannabidiol) to treat a rare, severe seizure disorder variant in children [27]. Providers will now be dealing with the requests from parents to use something to treat autism that may, in fact, according to the latest data, have had a hand in the creation of the condition in the first place [28, 29]. Unless the parents choose to accept the risks and give their child what they have been able to purchase for recreational use without any awareness of safe prescribing and dosing.

Discussion Points for Education and Management

As legalization continues, so does the rise of pregnant women choosing to continue their prepregnancy use or seek ways to alleviate pregnancy symptoms. In 2016, Volkow and associates reported a more than 60% rise among pregnant women from 2002 to 2014 [30]. Citing “some sources on the internet” as recommending cannabis products to combat nausea and vomiting associated with early pregnancy; the discussion about exposure and risks needs to start before women ever conceive (Fig. 16.4). In clinical practice, if a pregnant woman reports persistent or recurrent nausea and vomiting beyond the typical first-trimester expectations, are they reporting unusual pregnancy-related symptoms, or have they crossed the threshold for cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome and worsening their symptoms with continued use [31]? A simple Internet search produces many links to information supporting the use and how to get marijuana products, but credible sources that discourage use take a little more digging. The less-than-credible sources cite the lack of data and growing legalization as a support for their cause. The points they appear to be missing are the experiences of the past.

An illustration of this point is found in thalidomide. When first introduced as an anticonvulsant, most taking the drug noted that it made the users sleepy. This agent was marketed as a mild sleeping agent safe for pregnant women and readily prescribed as such, although none of the safety testing involved pregnant animals. In 1962, limb anomalies were linked to the use of the drug, and its use in pregnancy was deemed unsafe, too late for the thousands affected. This shift from presuming safety to proving it began a lengthy process involving clinical trials and testing that are now commonplace in medical practice [32]. The difficulty for marijuana is the schedule I classification that may impact drug study as well as the ethical feasibility of designing a trial. However, it is not only the study of cannabis itself. A Utah legislative subcommittee recently declined fund appropriation to study the prevalence of cannabis and opioid use among pregnant women, a study anticipated to assist in designing educational programs [33]. As the legalization wave continues, so, too, does the normalization of its use without understanding the dangers it may be imposing.

In their 2015 review, Drs. Metz and Stickrath sought to provide clinicians with a practical review of existing literature and recommendations for practice [34]. They discussed the variable opinions surrounding marijuana as producing little or no harm among pregnant women as a barrier to education and likely contributing to its use in pregnancy. They further detail many of the aforementioned concerns for developmental and neurobiologic alterations found in fetal brains as further support for the teratogenic effects imposed by prenatal cannabis exposure. There is also evidence that marijuana use can inhibit prolactin, essential for maternal milk production, in addition to continued exposure if the mother does not discontinue use while breastfeeding [13].

We are, then, left to determine the effects after children have already been affected. Fine et al. examined the complexity of early neurological development by examining the effects of maternal mental illness as an example of child risk [3]. These effects were evident not only in infancy but through to adolescence as structural brain changes, emotional and behavioral problems, as well as infant temperament, development, and cognitive functioning in later years. Because fetal/neonatal/infant development can be impacted by a host of environmental, teratogenic, and neurobiologic factors, it is difficult to isolate a sole causative source, but the data surrounding the effects of cannabis is emerging. From overall birthweight to heart defects and links to rising rates of autism, study after study is demonstrating more convincing evidence that cannabis is harming our children. Although more study is warranted to facilitate evidence-based education for families, we should be sharing what we do know.

Conclusion

Despite the difficulties with effectively studying the effects of marijuana exposure during the perinatal and neonatal periods, the available data is troubling at best. Concerns for learning, attention, focus, and even placement on the autism spectrum mentioned earlier in this chapter must be the focus as the medical community seeks to educate prospective and new parents. The information from outside medicine most certainly exists and can make marijuana and THC appear harmless, and even helpful, as an alternative to the standards of obstetrical and newborn care, as evidenced by the 70% of Colorado marijuana shop owners recommending its use in the first trimester of pregnancy [35], although some states are now requiring signs warning of the dangers posed by THC use during pregnancy and breastfeeding be posted. From combating first-trimester nausea to relieving the aches and pains of changing physiology and help with sleeping, marijuana is being advertised and, in some cases, being recommended as a panacea ‘fix-it-all’. Data is also emerging about the occurrence of intractable vomiting and psychosis associated with marijuana presenting to emergency departments across the country, which begs the question of safety for anyone.

Maternal educational exemplar from state of Washington. (https://www.knowthisaboutcannabis.org/your-health/)

At chapter header, at breast

At chapter header, 30 weeks

At chapter header, 4D ultrasound 36 weeks

At chapter header, 4D ultrasound 6 weeks