1: At each and every moment, I can decide who I am

Heinz von Foerster on the observer, dialogic life, and a constructivist philosophy of distinctions

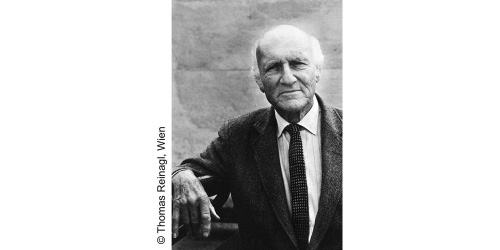

Heinz von Foerster (1911-2002) is held to be the “Socrates of cybernetics”. Having studied physics in Vienna, he worked in various research laboratories in Germany and Austria, and after World War II also briefly as a journalist and as a consultant to a telephone company. At the same time, he wrote his first book, Memory: A quantum-mechanical investigation (published in Vienna, 1948). His theory of memory caught the attention of the founding figures of American cybernetics. They invited him; he immigrated to the USA in 1949. There, he was received into a circle of scientists that began to meet in the early fifties under the auspices of the Macy Foundation. He was made editor of the annual conference proceedings. The mathematician Norbert Wiener, whose book Cybernetics had just been published, John von Neumann, the inventor of the computer, the anthropologists Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, the neuropsychiatrist Warren S. McCulloch, together with more than a dozen other intellectual enthusiasts, formed the group essentially contributing to the so-called Macy Conferences.

In 1957, Heinz von Foerster was meanwhile appointed professor, founded the Biological Computer Laboratory (BCL) at the University of Illinois, which he directed until his retirement in 1976. At this institution, he brought together avant-garde artists and original minds from all over the world. In the inspiring climate of the BCL, philosophers and electrical engineers, biologists (e.g. Humberto R. Maturana and Francisco J. Varela), anthropologists and mathematicians, artists and logicians debated epistemological questions from interdisciplinary perspectives deriving from both the sciences and the arts.

They dealt with the rules of computation in humans and machines and analysed the logical and methodological problems involved in the understanding of understanding and the observation of the observer. It is von Foerster’s outstanding achievement to have brought into focus the inescapable prejudices and blind spots of the human observer approaching his apparently independent object of inquiry. His ethical stance demands constant awareness of one’s blind spots, to accept, in a serious way, that one’s apparently final pronouncements are one’s own productions, and to cast doubt on certainties of all kinds and forms, while at the same time continually searching for other and new possibilities of thought.

The myth of objectivity

Poerksen: Every theory, every attitude, or worldview, rests on its own aphorisms and key statements that, if one probes their depths and thinks them through, encompass what is essential. Psychoanalysts follow Freud’s thesis that humans are “not masters in their own house” because the subconscious reigns supreme there. The central formula of Marxism is: “Being determines consciousness.” (“Das Sein bestimmt das Bewusstsein.”) The behaviourist Skinner upholds the determinist thesis “Human behaviour is the function of variables in the environment.” One of the key aphorisms of constructivism and your own world of ideas, it seems to me, may possibly be located in the writings of your friend, the biologist Humberto Maturana: “Anything said is said by an observer.”

Von Foerster: The entree you have chosen seems very interesting to me - for there is always the question: With what claims and assumptions should we approach an area of thought? Where, how and when should we begin with the telling of a story? Moreover, what will happen afterwards? Will people pound their fists on the table and declare everything nonsense, or will they smile at you full of excitement? Considering Maturana’s theorem in isolation and without all its implicit consequences will certainly not earn you special admiration. Nobody will exclaim: “Wow! What a revelation!” You might rather hear: “My God, if this is the fundamental tenet of his philosophy, then I prefer to go to the cinema or have a drink.” This theorem, without its proper context, may appear ridiculous, annoying, or downright stupid.

Poerksen: What are some of the epistemological consequences - to formulate the question quite generally - if we take the statement seriously and try to build a system of thought upon it?

Von Foerster: One of the conclusions is that what a human being comprehends can no longer be externalised and be seen simply as given. The statement undermines our craving for objectivity and truth for we must not forget that it is a distinguishing feature of objective and true descriptions that the personal properties of the observer do not enter into them, do not influence or determine them in any way. They must not, it is claimed, be distorted or disturbed by an observer’s predilections, personal idiosyncrasies, political or philosophical inclinations, or any other kind of club affiliation. I would say, however, that this whole concept is sheer madness, absolutely impossible. How can one demand a thing like that - and still remain a professor?! The moment you try to eliminate the properties of the observer, you create a vacuum: There isn’t anyone left to observe anything - and to tell us about it.

Poerksen: The observer is the component that cannot be eliminated from a process of knowing.

Von Foerster: Exactly. There must always be someone who smells, tastes, hears, and sees. I have never really been able to understand, what the proponents of objective descriptions want to observe at all if they ban the human observer’s personal view of things right from the start.

Poerksen: “Objectivity is a subject´s delusion,” the American Society for Cybernetics quotes you, “that observing can be done without him.”

Von Foerster: How can we get round the question: What can observers perceive who, according to the common definition of objectivity, are in fact blind, deaf and dumb, and who are not allowed to use their own language? What can they tell us? How are they to talk? Only an observer can observe. Without an observer, there is nothing.

Poerksen: If we, as you suggest, tie knowing inseparably to the knower, what sense and what function remains for the key concepts of realism, e.g. reality, fact, and object?

Von Foerster: If used at all, they will only serve as crutches, metaphors, and shortcuts. They may be used to state things and establish relations, without delving more profoundly into the questions involved. They will facilitate quick reference to specific points of relevance - a place, an object, a property - which are supposed to exist in the world, and to formulate corresponding statements. The danger lies in it being all too easy to forget that we are using crutches and metaphors and to believe that the world is really and truthfully represented by our descriptions. And that is the moment in which conflicts and hostilities and wars arise about the question what the facts are and who is in possession of the truth.

Poerksen: To take the knower - the observer - seriously also entails supplementing or even replacing ontological questions concerning the What - the object of knowing - by epistemological questions relating to the How - the process of knowing. What insights or perhaps what experiences have induced you personally to focus on the observer in your research and in your reflections? Was there an intellectual key experience?

Insights of a magician

Von Foerster: The experience occurred a very long time ago. At twelve or thirteen years of age, my cousin Martin and I - we grew up together like two inseparable brothers - began to practise magic. We invented our own acts, stunned the amazed grown-ups with our enthusiasm, and realised after a while that magic had nothing to do with mechanical things, false bottoms, tricks, optical illusions etc., which everybody is familiar with; the decisive thing was to create an atmosphere in which something unbelievable, something unexpected could happen, something nobody had ever seen. It is the spectator who invents a world in which girls are sawn apart and elephants float through the air. What instilled an awareness of the observer into me was the question: How can I create an atmosphere for a group of people, in which miracles may be seen? What sort of story must I tell, how must I tell it in order to make people accept it and make them work the miracles of the floating elephant and the sawn girl in their own individual ways? As a child or a youngster you simply perform your magic acts, you listen in amazement to what the grown-ups tell you about what they have seen, and perhaps you wonder what goes on in their brains. And this is what you later - when you are fifty, perhaps - describe as the observer problem.

Poerksen: Magicians are, if I am not mistaken, practising constructivists; they create visions and construct realities, which contradict the laws of gravity as well as the rules of probability and everyday life.

Von Foerster: This is the point. Magic, for me, was the original experience of constructivism: together with the other participants you invent a world in which elephants disappear and girls are sawn apart - and suddenly re-appear totally unharmed. What amused me and my cousin most was that the spectators who had apparently all seen the same event - the magic trick - often related quite different variations in the interval or after the show, which had nothing or very little to do with what we or other magicians had done. Mr Miller, Mr Jones, and Ms Cathy obviously created their own personal events. They saw girls sawn apart that were not, of course, sawn apart at all, neither had the elephants been made to vanish. These experiences drew my attention to the psychology of observing and the creation of a world: What happens, I asked myself, in the process of observing? Is that observer sitting in Hermann von Helmholtz’s famous locus observandi and describing the world in a state of complete neutrality?

Poerksen: What do you think? What is the observer doing? What is going on?

Von Foerster: The customary view is: the observer sees the world, perceives it, and says what it is like. Observers supposedly occupy that strange locus observandi and watch - unconstrained by personality, individual taste, and idiosyncratic features - an independent reality. In contrast, I maintain that observers in action primarily look into themselves. What they are describing is their view of how the world appears to them. And good magicians are able to sense what kinds of world other persons would like to be real, at a certain moment, and they can help them to create these worlds successfully.

Poerksen: The magician’s act, technically speaking, involves three components: the magician, the event, and the spectators. If we asked a solipsist, a realist, and a constructivist to describe what was happening, we would get quite different accounts. The solipsists would tell us that nothing of what they describe is real, but that everything is a chimera of our minds merely imagining the magician as well as a world that does not, in fact, exist. The realists would insist that observing is nothing but the mapping of reality onto the screen of our mind - and that the observers, the spectators, are deceived by the magician’s trickery: they fall victim to an illusion that does not adequately represent the reality of what is independently existent. Your kind of constructivism occupies the middle ground between realism and solipsism: There is something there, you would probably say, something is really going on, and that seems beyond doubt; but it is just as certain that all human beings describe the reality of those events in their own ways and construct their very own worlds.

Von Foerster: I have an uncanny feeling that the language we are using at this moment in our conversation is playing tricks on us and producing all sorts of strange bubbles. You know what I want to talk about, and I know more or less, what I want to say. Still, I am not sure whether this kind of epistemological classification and this manner of linguistic embedding would enable other persons to grasp what you and I are getting at. This means: we must, for a moment, consider the language we use to express what we mean. The mere sentence “There is something there” seems to me to be poisoned by the presuppositions of realism. I am worried that the position you assign to me is holding some backdoor open through which that terrible notion of ontology may still gain entrance. Accepting this position, one may continue to speak of the existence of an external reality. And referring to an external reality and existence is a wonderful way of eliminating one’s responsibility for what one is saying. That is the deep horror of ontology. You introduce the apparently innocent expression “there is...” which I once jokingly and somewhat pompously termed the existential operator and say with authoritarian violence: “It is so... there is...” But why is what there? And who asserts that something is the case?

Poerksen: The fact that you reject any prefabricated terminology and show a noticeable aversion towards any clean and, as it were, unadulterated epistemological classification of your ideas, seems to me to be an important indication of a fundamental problem: How can we speak about the act of observing, the observer, and the observed, in a way that does justice to the dynamic processes involved?

Von Foerster: This is an incredibly difficult problem because we are working with a medium - language. Being tied to that medium, we are seduced to speak in a way that suggests the existence of a world independent from us. One of my great desires is to learn to control my language in such a way as to keep my ethics implicit, whether I am dealing with politics, science, or poetry, so that it is always evident that I myself am the point of reference of the observations I am offering. I would like to invent a language or form of communication - and perhaps it will have to be poetry, music, or dance - that would release something in another person, so that any reference to an external world or reality, to any “there is...” would be superfluous; any such reference, so I imagine, would no longer be needed. To do this successfully, however, one must be firmly anchored in that world. Moreover, one problem always remains: What other form can we invent that would also deal with the problem of form?

Poerksen: In my view, the actual question is: How can we speak or write in such a way as to make the observer-dependence of all knowledge visible whenever we speak or write? How can we show that our descriptions of the world are not the descriptions of an external reality but the descriptions of an observer who believes they are descriptions of an external reality?

Von Foerster: The problem is a dialogue between you and me that does not rely on any reference to something external. When I insist, for instance, that it is you producing this view of things, that it is not something out there, not the so-called objective reality, that we can fall back on, then a strange foregrounding of you, the person speaking, is effected. Generalised expressions beginning with “There is...” are replaced by expressions beginning with “I think that...” We use, to say it somewhat pompously again, the self-referential operator “I think...” and abandon the existential operator “there is.” In this way, a completely different relation emerges that paves the way for a free dialogue.

Poerksen: If you do not want to talk about subject, object, and the process of knowing - the observer, the observed, and the process of observing - on the basis of a form of language established i n the academic world i nvolving classic epistemological concepts, what ways of talking can we turn to?

Separation or connection

Von Foerster: I cannot offer a general solution but I would like to present a short dramatic scene that I once wrote because it might help to escape the grip of predetermined forms. The scene is performed for an audience in a baroque theatre. The lights are dimmed, the impressive red velvet curtain rises, and the stage comes into full view. There is a tree, a man, and a woman, all forming a triangle. The man points at the tree and says: “There is a tree.” - The woman says: “How do you know that there is a tree?” - The man: “Because I see it!” - With a brief smile, the woman says: “Aha!” - The curtain comes down. - I contend, this drama has been discussed, misunderstood, and even attacked for thousands of years, a drama that is well suited to illuminate the debates of questions of knowledge and the role of an external world. Whom do we want to trust, whom do we want to refer to? The man? The woman? Since primeval times, the undecidable question has been haunting us whether to side with the man or with the woman. The man affirms the observer-independent existence of the tree and the environment, the woman draws his attention to the fact that he only knows of the tree because he sees it, and that seeing is, therefore, primary. We must now ask ourselves which of these attitudes we are prepared to accept. The man relies on his external reference, the woman points out to him that the perception of the tree is tied to his observation. However, this little piece does not only deal, as might be suspected, with objectivity and subjectivity or different epistemological positions. Something else is much more important: The man separates himself from the world, the woman connects herself with what she describes.

Poerksen: This is, then, another contrast that comes into play here. It is not primarily concerned with the distinction between subjectivity and objectivity but with the question as to whether I connect myself to the world, or whether my epistemological position forces me to see myself as distinct from it, as a person observing it from an imaginary locus observandi.

Von Foerster: This is a good way of putting it. The man in my little drama looks at the passing and unfolding universe as if through a keyhole, at the trees, the things, and the other people. He does not have to feel responsible, he represents a sort of keyhole or peephole philosophy, he is a voyeur. Nothing concerns him because nothing touches him. Indifference becomes excusable. The woman insists that it is only a human being can see and observe. The attitude of the detached describers is opposed to the attitude of the compassionate participants who consider themselves as part of the world. Each one acts on the basis of the premise: Whatever I do, will change the world! I am the world, and the world is me!

Poerksen: What are the consequences of this experience or knowledge of connectedness?

Von Foerster: What we call the world is, all of a sudden, no longer something hostile but appears to be an organ, an inseparable part of one’s own body. The universe and the self have become united. We have to shoulder responsibility for our actions; we can no longer retire to the position of the passive recorder who describes a static and supposedly timeless existence. We have been made aware that every action - even the mere lifting of an arm - may create a new universe that did not exist before. Knowing this - or better, sensing it and feeling it - excludes any kind of static vision; on the contrary, everything is now in constant flux, every situation is new, nothing is eternal, nothing can ever be as it once used to be.

Poerksen: I am quite in favour of this description of an observer-dependent universe. Nevertheless, objections immediately come to mind. We perceive the world as something that has developed and grown, and the experience of the stability of our human condition is definitely quite comforting. Its regularities seem reliable, they provide orientation, allow us to make plans and to face the future with certain expectations. What I want to say is: The attitude you describe contradicts our everyday experience and it is, in addition, psychologically unattractive.

Von Foerster (laughing): Absolutely right. I completely agree with you.

Poerksen: You agree with me? Do you not want to convince me of the correctness of an observer-dependent state of the world?

Von Foerster: For God’s sake! I would not dream of trying to convince you because that would cause your view to vanish. It would then be lost. All I can attempt is to act the magician so that you may be put in a position to convince yourself. Perhaps I might succeed in inviting you to re-interpret, for a moment, the security you find so attractive as something undermining openness. For even security and stability of circumstances may get persons into great trouble at certain stages in their lives, when they, for instance, do not realise that the circumstances constraining them might be completely different ones, and that it is in their power to change them.

Poerksen: As you are unwilling to convince me, what is, then, for you, the purpose of a dispute or a conversation?

Von Foerster: I would like to answer with a little story about the world of Taoism, which has fascinated me since childhood. My uncle, Erwin Lang, was taken prisoner by the Russian forces soon after the outbreak of World War I and deported to Siberia. When the Russian Empire collapsed in 1917, he managed to escape to China. He finally reached the German settlement Tsingtau where he met the scholar Richard Wilhelm, the translator of the I Ching, who introduced him to the ideas of Taoism. Through his help and recommendation, Erwin Lang was accepted by a Taoist monastery at which he arrived after a two days walk. Still uncertain whether the War was over and the fighting had stopped, he asked one of the monks for newspapers. Of course, the monk said, we have newspapers; we have, in fact, an enormous library. My uncle was impressed and asked for a copy of the Austrian Neue Freie Presse. Certainly, the monk said, we have newspapers from all over the world. He took him to the archive in the monastery and, after a short search, produced the most recent issue of the Neue Freie Presse available. It was the issue of 15 February 1895. Of course, Erwin Lang was somewhat consternated and pointed out to the monk that the paper was more than 20 years old. The monk looked at him and said: “So what?! What are 20 years?” At that moment, my uncle began to understand Taoism: Time did not play any role in this world; topical news value was of no importance.

Poerksen: You are unwilling to convince me, and you refuse to discredit other, or antagonist, positions, but you use history and stories - your little parable seems a case in point - in order to make further possibilities of perceiving accessible.

Von Foerster: This interpretation is most welcome. My goal is indeed to present different perspectives that may, or may not, be taken up. To return to the beginning of our conversation: Whether we accept the theorem of my friend, Humberto Maturana (“Anything said is said by an observer”), and whether we consider ourselves connected with the world or separate from it, - we are confronted by undecidable questions. Decidable questions are, in a certain sense, already decided through their given framework; their decidability is secured by specific rules and formalisms - for example, syllogisms, syntax, or arithmetic - that must be accepted. The question, for instance, whether the number 7856 is divisible by two, is easy to answer because we know that numbers with an even final number are divisible by two. Paul Feyerabend’s notorious slogan, anything goes, does not apply here because the rules of arithmetic force us to proceed in a certain way in order to find an answer. Undecidable questions, on the contrary, are unsolvable in principle; they can never really be clarified. Nobody knows, I would claim, whether the man or the woman in my little drama is right, and whether it is more correct to consider oneself connected with the world or separate from it. This situation of fundamental undecidability is an invitation to decide for oneself. For this decision, however, one must shoulder the responsibility oneself.

Monologic and dialogic

Poerksen: Reviewing our conversation about the observer, I cannot help noticing that you keep returning to the interaction of human beings. To put it differently, as a kind of thesis: For you, observers are not isolated figures; they always exist in a field of relations, in a community. Your own ideas, too, always appear embedded in actual relationships, in personal experiences and personal thoughts.

Von Foerster: The observer as a strange singularity in the universe does not attract me, indeed; you are quite right there. This kind of concept will probably be of interest to a neurophysiologist or neuroanatomist, whereas I am fascinated by images of duality, by binary metaphors like dance and dialogue where only a duality creates a unity. Therefore, the statement that opened our conversation - “Anything said is said by an observer” - is floating freely, in a sense. It exists in a vacuum as long as it is not embedded in a social structure because speaking is meaningless, and dialogue is impossible, if no one is listening. So I have added a corollary to that theorem, which I named with all due modesty Heinz von Foerster’s Corollary Nr. 1: “Everything said is said to an observer.” Language is not monologic but always dialogic. Whenever I say or describe something, I am after all not doing it for myself but to make someone else know and understand what I am thinking or intending to do.

Poerksen: What happens when other observers are involved?

Von Foerster: We get a triad consisting of the observers, the languages, and the relations constituting a social unit. The addition produces the nucleus and the core structure of society, which consists of two people using language. Due to the recursive nature of their interactions, stabilities arise; they generate observers and their worlds, who recursively create other stable worlds through interacting in language. Therefore, we can call a funny experience apple because other people also call it apple. Nobody knows, however, whether the green colour of the apple you perceive, is the same experience as the one I am referring to with the word green. In other words, observers, languages, and societies are constituted through recursive linguistic interaction, although it is impossible to say which of these components came first and which were last - remember the comparable case of hen, egg, and cock - we need all three in order to have all three.

Poerksen: I do not want to over-interpret this transformation of a monologic idea, which is tied to a single observer, into a dialogic concept involving two or more observers in interaction, but it seems to me to contain some hidden anthropology; not a hierarchic one, to be sure, which would compare human beings with machines, animals, or gods, but an anthropology of relations, of interdependence, of You and I. When you relate one human being to another, you are reflecting on the essence of humanity and its potential: there is one human being and there is another - this seems to me to be your point of reference.

Von Foerster: Very well put, indeed. A human being is a human being together with another human being; that is what a human being is. I exist through another I, I see myself through the eyes of the Other, and I shall not tolerate that this relationship is destroyed by the idea of the objective knowledge of an independent reality, which tears us apart and makes the Other an object which is distinct from me. This world of ideas has nothing to do with proof, it is a world one must experience, see, or simply be. When one suddenly experiences this sort of communality, one begins to dance together, one senses the next common step and one’s movements fuse with those of the other into one and the same person, into a being t hat c an see w it h f our e yes. Realit y b ecom es communality and community. When the partners are in harmony, twoness flows like oneness, and the distinction between leading and being led has become meaningless. In my view, the best description of this sort of communality is by Martin Buber. He is a very important philosopher for me.

Poerksen: Buber is not just the protagonist of a dialogic philosophy but also a religious scholar and writer, and a mystic. For him, the dialogue between an I and a You mirrors the eternal dialogue with God.

Von Foerster: I feel deep respect for his religious beliefs and feelings but I am unable to share them, really, and perhaps would not like to, anyway. Should his religious orientation be the source of his incredible strength and depth, I can only admire him the more.

Poerksen: What were the seminal experiences that oriented you towards a dialogic life?

Von Foerster: Among the most important is an encounter with the Viennese psychiatrist and pastoral curer of souls, Viktor Frankl. He had survived the concentration camp but had lost his wife and his parents, and he practised again in the psychiatric institution in Vienna from where he had been deported years before. A married couple had also miraculously survived the Nazi terror, each partner in a different camp. Husband and wife had returned to Vienna, had found each other, had naturally been overjoyed to find the partner alive, and had begun a new life together. About a month after their reunion, the wife died of a disease she had contracted in the camp. The husband was absolutely shattered and desperate; he stopped eating and just sat on a stool in his kitchen. Finally, friends managed to persuade him to go and see Viktor Frankl whose special authority as a camp survivor was beyond doubt. Both men talked for more than an hour - then Frankl abruptly changed the topic and said: “Suppose, God gave me the power to create a woman completely identical with your wife. She would crack the same jokes, use the same language and the same gestures, - in brief, you would be unable to spot any difference. Do you want me to ask for God’s help in order to create such a woman?” - The man shook his head, stood up, thanked Frankl, left his practice, and started up his life again. When I heard about this story, I went to see Frankl immediately - we were working together professionally on a radio programme broadcast every Friday, at the time, and I asked him: “Viktor, how was that possible? What did you do?” - “Heinz, it is very simple,” Frankl said, “we see ourselves through the eyes of the other. When she died, he was blind. But when he realised that he was blind, he was able to see again.”

In the beginning was the distinction

Poerksen: Perhaps we could now, with a modest topical jump, leave all types of observers behind, and deal with the process of observing itself. Every observation, George Spencer-Brown writes in his famous treatise Laws of Form, begins with an act of distinction. More precisely: observations operate with two-valued distinctions one of which may be designated. Therefore, if I want to designate something, I have to decide about a distinction first. The choice of a distinction determines what I can see. Using the distinction between good and bad I can - wherever I am looking - observe other things than when I am using the distinctions between rich und poor, beautiful and ugly, new and old or ill and healthy. And so on. Consequently, observing means distinguishing and designating.

Von Foerster: Correct, yes. George Spencer-Brown formulates: “Draw a distinction and a universe comes into being.” The act of distinction is taken to be the fundamental operation of cognition; it generates realities that are assumed to reside in an external space separated from the person of the distinguisher. A simple example: We draw a circle on a piece of paper; we create, in this way, two worlds, one outside and one inside, which may now be designated more precisely. In other words, if we follow George Spencer-Brown’s argument, before something can be named or designated, before we can describe the space within the circle more exactly, the world has been divided into two parts: it now consists of what we have named, on the one hand, and what is obscured by the name, the rest of the world, on the other.

Poerksen: When you encountered these ideas - you wrote one of the first widely noted reviews of Laws of Form - what fascinated you, in particular?

Von Foerster: What fascinated me, at the time, and still fascinates me now, is that the formal apparatus, the logical machinery, which Spencer-Brown developed, enables us to solve the classical problem of the paradox that has troubled logicians ever since the days of Epimenides. Epimenides, a Cretan, said: “I am a Cretan. All Cretans lie.” He might as well have said: “I am a liar!” What do you do with someone who says: “I am a liar”?! Do you believe him? If so, he cannot be lying, he must have told the truth. If he told the truth, however, he lied, because he said: “I am a liar.” The ambivalence of this statement is that it is true when it is false, and that it is false when it is true. The speaker steps inside what is spoken, and all of a sudden, the function turns into an argument of itself. Such a statement is like a virus and may destroy an entire logical system, or a set of axioms, and cannot, of course, be acceptable to honest logicians following the Aristotelean creed: “A meaningful statement must be either true or false.” In the twentieth century, Bertrand Russell and Albert North Whitehead attempted to resolve the liar-paradox by simply prohibiting, as it were, self-referential expressions of this kind. Their theory of types and their escape into a meta-language, however, did not seem satisfactory to me. I have always thought, although I did not know an elegant solution, that language itself ought to be the meta-language of the logicians. Language must be able to speak about itself; that is to say, the operator (language) must become the operand (language). We need a sort of salto mortale. George Spencer-Brown has developed an operator that is constructed in such a way as to permit application to itself. His operator can operate on itself and, in this way, becomes part of itself and the world it creates.

Poerksen: How can these ideas be related to epistemology, in particular, to the observer, the central figure of our conversation?

Von Foerster: Whenever I want to say something about myself - and I maintain that everything I am saying is said about myself - I must be aware that speaking involves a fundamental paradox that has to be dealt with. George Spencer-Brown’s formalism bridges the customary division between seeing and seen. The epistemology we might envisage against this background is dynamic, not static. It has to do with becoming, not being. Spencer-Brown refuses to start out from the supposition that a statement can only be true or false; the formalism invented by him reveals the dynamics of states. As in a flip-flop mechanism, the truth of an expression generates its falsity, and its falsity generates its truth, and so on. He shows that the paradox generates a new dimension: time.

Poerksen: I think it would be worthwhile to describe the philosophy of distinctions that has developed since the publication of Laws of Form in detail. Let me, therefore, ask you: What will happen, for example, when I introduce the distinction between good and evil into the world and make it the foundation of my observations?

Von Foerster: The distinction between good and evil and the universe created in this way may be used to form sentences and to make statements. Now, it is possible to say of an elephant or of a company director that they are good or particularly wicked. We can build up a calculus of statements, cascades of expressions, which deal with human persons, animals, directors, or elephants. What tends to be overlooked usually is that these distinctions are not out there in the world, are not properties of things and objects but properties of our descriptions of the world. The objects there will forever remain a mystery but their descriptions reveal the properties of observers and speakers, whom we can get to know better in this way. The elephants have no idea of what we are doing, the elephants are simply elephants; we make them good or wicked elephants.

Poerksen: Is it correct to say, as you claim, that the intrinsic properties of objects and things in the world do not become effective in our descriptions?

Von Foerster: In my view, objects correspond to the sensorimotor experience of a human being who suddenly realises that it cannot simply move everywhere, that there is something blocking its movement, something standing in the way, some ob-ject. This limitation of behaviour generates objects. As soon as I have acquired enough practice and have experienced these objects often enough, some stability in the experience of limitation has developed and I am in a position to give a name to the item of my sensorimotor skill and competence, call the ob-ject a cup, or glasses, or Bernhard Poerksen. This is to say: What I designate as glasses or cup is, strictly speaking, a symbol for my nervous system’s competence to generate stabilities, to compute invariants.

Poerksen: What sort of truth status would you claim for this thesis? Is it an ontologically correct theory of object formation; are objects really constituted in this way?

Von Foerster: Let me return the question: What do you think? What would you prefer, what would you like better?

Poerksen: Are you suggesting it is a matter of taste?

Von Foerster: If you want it this way, then it may also be a matter of taste. If you, however, prefer to live in a world where the properties of your descriptions are the properties of the world itself, then that is fine.

Poerksen: People will condemn this as absurd.

Von Foerster: Naturally, this is one of the usual reactions to someone thinking along different lines. The persons that come up with objections of this kind will have to live with the consequences. They create this world for themselves. I am only myself, I am rolling along, I can only try to communicate what I like, what I see, what I find fascinating, and what I want to distinguish. Whether other people consider me a scientist, a constructivist, a magician, a philosopher, a curiosologist, or simply a brat, that is their problem; and it is due to the distinctions they draw.

Blind to one’s own blindness

Poerksen: For you, the individual - socially anchored, of course - is evidently the central reality-creating instance. The sociologist Niklas Luhmann, however, who refers explicitly both to Spencer-Brown and your work, only speaks of the operation of observing, - never the observer. He wrote book after book on science, art, religion, politics, and economics, reconstructing the forms of observation and the central sets of distinctions at work in these social domains, to which everyone entering them must necessarily orientate.

Von Foerster: Le me just point out that society, too, is a relational structure; it is a framework according to which we may, but need not, think. In my work, however, the self and the individual are central and present from the start. The reason is that I can conceive of responsibility only as something personal, not as dependent on anything social. You cannot hold a society responsible for anything - you cannot shake its hand, ask it to justify its actions - and you cannot enter into a dialogue with it; whereas I can speak with another self, a you.

Poerksen: What you mean is, I think, that observers - human beings - can indeed decide what distinctions they want to make. My objection is that the world never is - in Spencer-Brown’s terminology - an unmarked space, but that we are all pressured in many ways, and even condemned, to reproduce the distinctions and views of our own groups, of parents, friends, and institutions. To quote but a blatant example: the children growing up in a sectarian community will obviously absorb its reality.

Von Foerster: This is possible, no doubt. On the other hand, I remain convinced that these people, these individuals, can always opt out of such a network and escape from the sectarian system. They have this freedom, I would claim, but they are all too often completely unable to actually see it. They are blind to their own blindness and do not see that they do not see; they are incapable of realising that there are still possibilities for action. They have created their blind spot and are frozen in their everyday mechanisms and think there is no way out. The uncanny thing, actually, is that sects and dictators always manage to make actually existing freedom invisible for some time. All of a sudden, citizens become zombies or Nazis committing themselves to condemning freedom and responsibility by saying: “I was ordered to kill these people, I had no choice! I merely executed orders!” Even in such a situation, it is obviously possible to refuse. It would be a great decision, possibly leading to one’s own death but still an act of incredible quality: “No, I will not do it. I will not kill anyone!” In brief, it is my view that freedom always exists. At each and every moment, I can decide who I am. Moreover, in order to render, and keep, this visible I have been pleading for a form of education and communality that does not restrict or impede the visibility of freedom and the multitude of opportunities but actively supports them. My ethical imperative is, therefore: “Act always so as to increase the number of choices.”

Poerksen: But how can we re-invent ourselves at each and any moment? Surely, that is out of the question; the world - all the inescapable constraints on our lives - simply will not allow it. Here is my counter-thesis: In the act of observing, we reproduce either old orders or systems of distinctions, or we develop new ones from or against them. Therefore, the freedom and arbitrariness of constructions is massively reduced.

Von Foerster: It is certainly not my contention that the invention of realities is completely arbitrary and wilful and would allow me to see the sky blue at first, then green, and after opening my eyes again, not at all. Of course, every human being is tied into a social network, no individual is an isolated wonder phenomenon but dependent on others and must - to say it metaphorically - dance with others and construct reality through communality. The embedding into a social network necessarily leads to a reduction of arbitrariness through communality; however, it does not at all change the essentially given freedom. We make appointments, identify with others and invent common worlds - which one may give up again. The kinds of dance one chooses along this way may be infinitely variable.

Drop a distinction!

Poerksen: If I understand correctly, human beings are - together with others - capable of creating reality, in a positive sense. However, what are we to do about realities that we reject and do not want to create at all? Can we escape from them through negation?

Von Foerster: No, I do not think so. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus-logico-philosophicus made me see this clearly for the first time. There is the famous consideration that speaking about a proposition “p” and its negation “non p” means speaking of the same thing. The negation is in fact an affirmation. This is the mistake committed by my dear friends, the revolutionaries, who want to depose a king. They keep shouting loudly and clearly: “Down with the king!” That is, of course, free propaganda for the king who should, in fact, thank his enemies: “Thank you very much for mentioning me so frequently and for not stopping to call out my name!” If I negate a person, an idea, or an ideal, loudly and clearly, the final separation has not yet been achieved. The negated phenomenon will return and take centre stage again.

Poerksen: Who wants to get rid of something finally must neither describe it positively nor deny it, in order to achieve complete separation. What is to be done, then?

Von Foerster: Something different must be done. I suggest that certain distinctions are excluded because I have noticed in many discussions that their basis involves concepts that lead nowhere but only generate conflicts and hostilities. The negation of stupidity is no less stupid because it forces us to go on dealing with stupidity. To make these considerations clear I should like to speak, for a moment, about the place-value logic devised by the philosopher Gotthard Günther. In his papers, he analyses the emergence of a proposition, its logical place. Even talking about a king who is then either celebrated or shouted down by revolutionaries requires, according to Günther, a certain place. However, this place may be refused in order to prevent any talk about kings. In this way, a new kind of logic arises. The simple dichotomy of affirmation and negation is left behind; certain propositions are marked with a rejection-value in order to make clear that they do not belong to the category of propositions under discussion.

Poerksen: Can you describe this kind of place - the basis that is required by every proposition as the condition of its possibility - more precisely?

Von Foerster: I think the Russians understood this idea very well. I once took part in a conference in Moscow in the era of Khrushchev who sought to bring about a new kind of interaction between bureaucrats and humankind. One day I took a stroll in one of the small parks near the Lenin mausoleum. I saw the statues of the Great Russian military leaders cut in stone and sitting on huge pedestals, staring into the void with their large moustaches. Suddenly I saw a pedestal without a statue, empty. Joseph Stalin cut in stone had once stood on it. In this way, the present government expressed its rejection of Stalin. Had the pedestal been removed as well - the place of the logical proposition in Gotthard Günther’s theory - this kind of negation would not have been possible. They were very well aware of that!

Poerksen: This means that we can get rid of concepts simply by stopping to mention them, relegating them to a domain of non-existence, taking away their pedestal and their foundation, as it were. They drop back into an amorphous and shapeless sphere, which is cognitively inaccessible to us because it is not marked by distinctions and indications. In this case, George Spencer-Brown’s fundamental imperative must be changed from “Draw a distinction!” to “Drop a distinction!”

Von Foerster: This is an excellent new operator: “Drop a distinction!” However, this sort of approach seems to have been known to journalists in Austria for some time; they say there that the best way of demolishing an idea or a person is to stop mentioning them. The formula is: “Do not even ignore!” If you want to destroy a politician and president of a country it is best not to write about his extramarital contacts with interns and other women; this would be wrong because the mere mentioning of his name makes people aware again of his existence and may make them say: What a handsome man! It is much more effective to speak about the weather and the weather frogs. And the politician immediately disappears.

Mysticism and metaphysics

Poerksen: Let me attempt a brief résumé. In the process of reality construction, we draw distinctions, we negate distinctions, reject them, try to distance ourselves from them, and sometimes drop them completely in order to get rid of unwanted concepts. We are left with the tricky question what might exist behind the universe that we have constructed. What exists beyond the space we have created through our distinctions? Can you offer an answer, perhaps a very personal one?

Von Foerster: Let me tell you a little story about a personal experience of mine. A few years ago, I was invited to a large conference and participated in a workshop called Beyond Constructivism, organised by a charming French lady scientist. People asked me, too, what was beyond constructivism. My answer was: “Ladies and gentlemen, last night, after I had heard of this workshop, I could not go to sleep for a long time because the question troubled me considerably. When I finally did catch some sleep, my grandmother appeared to me in a dream. Of course, I asked her instantly: “Grandmama, what is beyond constructivism?” - “Do not tell anyone, Heinz,” she said, “I will let you in on the secret - constructivism!”

Poerksen: We can never go beyond our distinguishing and constructing of worlds.

Von Foerster: Exactly. The distinction creates the space. Without this basis, you cannot ask the question regarding the space and the world beyond the space.

Poerksen: Still, if we are to believe the reports of eastern mystics, there seem to be states of consciousness that are not constrained by the ordinary human forms of distinctions. Concluding your review of Laws of Form, you refer yourself to a “state of ultimate wisdom” and to the “core of a calculus of love in which all distinctions are suspended and all is one.”

Von Foerster: That is indeed what I wrote; no more need be said because that is precisely what I wanted to say. I would be grateful if we could simply let that utterance be as it is and not take it to pieces as in an academic seminar.

Poerksen: It seems to me that you have developed a way of speaking that offers indications and hints at things you do not want to pursue any further once you have drawn attention to them.

Von Foerster: I am concerned with inviting people to look. If you are prepared to look, you may see, but you have to look first. This is what I want to make clear.

Poerksen: What do you want to show?

Von Foerster: That it is possible to show. Whatever someone sees is up to them.

Poerksen: I do not follow.

Von Foerster: I understand. However, in many cases, unanswerability and answerlessness generate insight.

Poerksen: What you call answerlessness, could just as well be the chiffre of a mystic: in this space of uncertainty we might again be able to envisage something absolute and “totally different “.

Von Foerster: The very attempt to understand something completely ordinary immediately confronts us with puzzles and wonders that we usually pass by and leave unnoticed in our everyday lives. Most of these cannot be explained in any serious sense; in my view, we will never be able to penetrate them and remove or even destroy their awesome quality. The knowledge we have of our world is to me like the tip of an iceberg; it is like the tiny bit of ice sticking out of the water, whereas our ignorance reaches far down into the deepest depths of the ocean. Such a claim of principled inexplicability and awesomeness undoubtedly makes me a mystic. I would be a metaphysician if I claimed to have an answer to this inexplicability.