2: We can never know what goes on in somebody else’s head

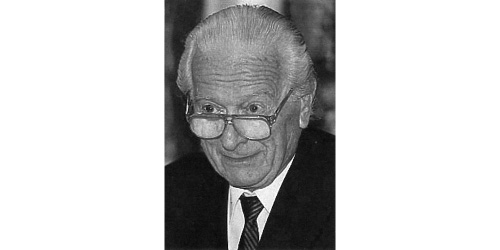

Ernst von Glasersfeld on truth and viability, language and knowledge, and the premises of constructivist education

Ernst von Glasersfeld (b. 1917) studied mathematics in Zürich and Vienna, was a farmer in County Dublin during the War, and worked as a journalist in Italy from 1947. There he met the philosopher and cybernetician Silvio Ceccato who, in the beginning stages of the computer age, had gathered a team of researchers in order to carry out projects of computational linguistic analysis and automatic language translation. Von Glasersfeld became a close collaborator of Ceccato’s, translated for him, and developed projects of his own. In 1966, he moved to the USA where he was made a professor of cognitive psychology at the University of Georgia in 1970. Three principal research interests have made him one of the well-known founders of constructivism. He systematically scoured the history of European philosophy for varieties of epistemological scepticism and set up an ancestral gallery reaching back to the insights of the ancient sceptics of the 4th century B.C. He replaced the classical realist concept of truth by the idea of viability: theories need not and do not correspond with what is real, he says, but they must be practicable and useful, they must be viable. Finally, he introduced the work of the Swiss developmental psychologist, Jean Piaget, into the constructivist debate.

Jean Piaget, in his book La construction du réel chez l’enfant, constructs a model of how knowledge is created and developed through the confirmation or disappointment of expectations (or more precisely: of particular patterns of action, so-called schemes). A model of this kind has profound consequences for the conception of learning and teaching: it eliminates the reification of information and knowledge, the conception of knowledge as a substance that can be transferred from the teacher’s head to the empty heads of students. The mechanical idea of teaching evaporates. We must face the ineluctable subjectivity of meanings and given cognitive patterns. From this perspective, the acquisition of knowledge no longer appears to be a passive reception of information but a creative activity. The upshot is that teaching someone something will only be successful if it is oriented towards the reality of that someone.

Ernst von Glasersfeld is, at present, with the Scientific Reasoning Research Institute of the University of Massachusetts. There he works on models of teaching and learning that apply the theory of constructivism to school practice.

The God’s eye view

Poerksen: According to the famous definition by Thomas Aquinas, truth is adaequatio intellectus et rei, the correspondence between mind and object. Idea and world agree, it is assumed, they enter into exact correspondence. The object and the predication about the object have the same structure, as it were. The school of thought of constructivism, whose prominent representative you are, challenges this correspondence-based conception of truth and insists that knowledge of truth according to this understanding is impossible.

Von Glasersfeld: I am certainly not the first nor the only one to take this view; the pre-Socratic philosophers already formulate it - just remember Xenophanes, the sophists, and the school of Pyrrhon. They were fully aware that the ideas human beings formed on the basis of their experiences could never mirror a reality independent from them. Xenophanes states that it can never be established whether some image of reality is completely correct because it is impossible to verify its correctness even if it were the case. We can never step outside our perceptual and conceptual functions; all our examinations and tests concerning the relation between image and reality as such are, in any case, inevitably shaped by our instruments of experience.

Poerksen: To grasp the truth, one would have to leave our bodies, if I follow your thinking, in order to observe the absolute from a completely neutral point of view.

Von Glasersfeld: Exactly. Some recent philosophers have called this view from outside “the God´s eye view.” The problem is now, however, that even God - if we want to regard Him/Her as a rational Being - is confronted by the very same problem: He/She needs an apparatus for experience - and that means that even God’s experiences would be dependent on that apparatus. I do not believe, however, that we can comprehend God. The God’s Eye View is a metaphor for the impossibility of attaining an uncorrupted image of reality as such.

Poerksen: This consideration appears to me somewhat anthropomorphist, to put it mildly. You are presenting God’s view as if it were - like our human view - conditioned and preformed by a priori categories and forms of perception.

Von Glasersfeld: If I decide to remain within the bounds of rationality, I can only use human reason, and human rational thinking is always anthropomorphic. I could, of course, argue like a mystic, as an apophatic theologian, who says: if God possesses all the ascribed qualities, if God is omniscient, ubiquitous, eternal, then God is obviously totally different from the world that we human beings experience. And as we abstract all our concepts from our world of experience we will never be able to comprehend God by means of our concepts. This view seems central to me for two reasons. Firstly, the mystics arguing in this way formulate the perfectly logical assumption that something that is believed to exist outside their world of experience can never be grasped in terms derived from that world of experience. Secondly, they explicitly separate rational knowledge from mystical knowledge; both these forms of knowledge may exist side by side but they are fundamentally incompatible. This is most important for me.

Poerksen: Is it not rather striking that we, in this conversation about the possibility of comprehending the absolute, immediately come to talk about God? My impression is that the way you speak about the absolute resembles the way certain mystics describe God as the Inconceivable and as the “entirely other” Being.

Von Glasersfeld: Perfectly right. Scientific and religious ways of speaking also resemble each other in that they often purport to offer absolute knowledge. I find that parallel also quite amusing at times. The belief of some scientists to propagate the truth can easily be revealed a delusion because in the history of science nothing ever stays the same; theories and models of reality constantly change.

Poerksen: However, you too, as long as you remain faithful to your premises, cannot know with complete certainty whether any one of these theories corresponds with absolute reality or not. The unconditional negation of a correspondence between world and idea would obviously be a sort of negative ontology, a further variety of absolutism.

Von Glasersfeld: It is quite conceivable, of course, that one of our constructions, by coincidence, turns out to be a perfect match; but even such a theoretical and, in my eyes, rather improbable possibility would still not be sufficient to justify and determine that we have been successful - that our assumptions correspond with absolute reality. If we assert that our conceptions correspond with the world, then we are, I believe, obliged to prove this correspondence. And if we fail to do so, then correspondence-based assertions merely have the status of unwarranted theses.

Poerksen: It seems to me that your criterion of truth is that we cease to exist as persons when we observe and that the knowledge we manage to acquire is strictly independent from the cognitive instruments we use. You demand something impossible, and therefore you are immune to any kind of criticism.

Von Glasersfeld: I do not feel insecure with my views at all, and I know that I am in very good company; as already mentioned, the sceptics have, since the time of the Pre-Socratics, repeatedly pointed out that we can never compare our image of reality with reality as such, but that we can only compare images with images. Innumerable philosophers have racked their brains in order to refute this claim; not a single one has succeeded in providing proof for the correspondence between world and idea. For this reason, they have turned to metaphysics, i.e. into mysticism.

The fault of evolutionary epistemology

Poerksen: May I start another attempt, and from a different perspective, to justify the belief that there must be some systematic connection between our perceptions and the real world? Surely, we could argue that the perceptual apparatus of humans has adapted to given realities through constant and sometimes fatal trials and errors during the course of evolution. This was the view of the ethologist and evolutionary epistemologist Konrad Lorenz, who thought that the course of evolution effected a gradual approximation of the Kantian thing-in-itself, the real world. Constructions that fail to match reality would simply be destroyed by the mechanism of natural selection.

Von Glasersfeld: As I see it, we must always keep in mind that the theory of evolution and all the perspectives that appear to follow from it necessarily, are only models that we have constructed and that may be replaced by other models tomorrow. This is Konrad Lorenz’s mistake, I think: he sees the theory of evolution as an ontological description, assuming that animals and humans have factually and in reality evolved in a certain way. Now this is an empirically well-founded hypothesis but empirical assumptions can never support ontology. We can certainly say that we have invented the categories of space and time because they are particularly useful and fit the reality of our experience. However, good functioning can never be proof of mirroring the external world. This is why I prefer to speak of viability in order to stress that we must always reckon with other possibilities of compatibility.

Poerksen: Konrad Lorenz formulates: “The adaptation to specific environmental conditions is equivalent to the acquisition of information about these environmental conditions.”

Von Glasersfeld: Adaptation - no matter how well an individual organism feels adapted to an environment - does not produce an exact representation of the environment; such a view is in my eyes logically false. Adaptation can only mean that we manage to get through, that we have found a viable course, that we do not fail. To the neurobiologist Humberto Maturana I owe the example of the instrumental flight, which illustrates our cognitive situation: there is the pilot in the cockpit, who has no access to an external world and only reacts to what the instruments indicate. Nevertheless, pilots successfully fly and land their planes, although thunderstorms may rage outside. The only thing they may notice of the thunderstorms is the occasional deviation of the instruments from their course, which they then immediately correct. They identify perturbations and react accordingly. They have no idea whatever of the actual cause, the thunderstorm, but manage to land safely and thus to reach their goal. We can state that they have got through. I would maintain that this situation of an instrumental flight corresponds exactly to our relationship with reality: we can never say what is outside the world of our experience.

Poerksen: If science is no longer concerned with understanding an external world and with spreading the truth in an emphatic sense, what is its task, what goal is it to serve?

Von Glasersfeld: I have the greatest respect for science but I would like to say that it should primarily deal with the urgent practical problems of human coexistence in our time. Here in the United States one should, for instance, not spend billions of dollars on particle accelerators as long as there are still people who have to sleep in the streets, and as long as industrial plants continue to damage and destroy the environment. I find this absurd but such a point of view is not particularly popular among scientists: they want to see scientific research as the highest form of human activity, which sets its own goals and keeps strict neutrality - no matter what happens elsewhere.

Poerksen: What specific criteria could then be laid down to distinguish a construction of reality in the form of a scientific theory from another? Its closeness to an imaginary pole of truth can no longer serve as a means of distinction, if I follow your thought.

Von Glasersfeld: The criterion that I have introduced is utility or viability. I have taken the concept of viability, which is closely related to the concept of adaptation, from the theory of evolution. It replaces, in the world of experience, the classical philosophical notion of truth, which assumes an exact representation of reality. An organism is viable, my definition would be, if it manages to survive under given constraints and environmental conditions. And I call modes of action and thought useful or viable if they help to achieve a desired goal by overcoming all given obstacles. The assessment of the viability of a construction is, however, dependent on one’s values. It contains a subjective element and requires a personal judgment. The choice of values, any ethical choice, cannot be justified by constructivism: we deal with decisions and rules that are not questionable.

Poerksen: Could you give an example of a viable theory?

Von Glasersfeld: Just think of the NASA space program; it is firmly based on Newton’s formulae when satellites are launched, directed to fly around the planet Saturn, or made to land on the moon. Nevertheless, there certainly is not a single scientist among the many working for NASA who would claim that Newton’s formulae, which were long ago overtaken by Albert Einstein, represented the truth. They were created for a particular purpose and they are still helpful and effective for all the relevant computations, no more and no less.

Poerksen: But how do we know, to put the question more generally, that something is useful or will prove useful in the future? This would require a prophetic gift because theories that appear viable right now may have the most terrible direct and indirect effects in the future. Therefore, we would have to integrate a time lag into the assessment of theories.

Von Glasersfeld: The practical implementation of a theory and its potential effects cannot always be foreseen, that is clear. I do think, however, that a scientist who spends public money is under the obligation to examine whether the theory he is working on offers possibilities of application that make things better or worse. Naturally, this is a relative matter and ultimately calls for a personal decision. The alternative would be an objective criterion in the sense of a representation of absolute reality; the idea would then be that science continually enlarges the domain of true knowledge, but that I consider impossible. A theory is only a model, which functions under particular circumstances - and not under others.

Poerksen: The fact, however, that the concept of viability is borrowed from the theory of evolution does suggest that it is meant to be a hard criterion for the differentiation of reality constructions. If an organism is not viable, if it cannot find a way to come to terms with the constraints of the environment, then it is, at the extreme limits, condemned to death. When a scientist formulates theories, then it is improbable that he will fail with them in a similar way.

Von Glasersfeld: Theories fail whenever observations or the results of experiments prove to be incompatible with them. False theories do not kill us, that is certainly true. But there are exceptions. The biologist and physician Alexander Bogdanov, who invented blood transfusion, proposed the theory that giving the patients a transfusion of healthy blood can cure particular diseases. Bogdanov did this once himself with a sufferer from malaria and something went wrong and both were dead within two days. But what are you driving at?

Poerksen: I want to point out that there are theories that cannot be falsified because it is, in a way, impossible to fail with them. Just think of the interpretation of a literary text, of a poem, which may lead different authors to fundamentally contradictory theories about its meaning. How would you show now which of the theories is useful and which is not?

Von Glasersfeld: This is, of course, a different area of knowledge. I would ask the persons involved in the hermeneutic activity why they are interpreting the particular poem. Are they doing it simply for their own pleasure, or do they, after all, also want to find out what other people are able to see in the text. If the latter, then we can ask: which one of two interpretations is convincing? Which of the two theories do educated readers consider more plausible? A higher measure of plausibility might be an indication of a sort of viability.

Poerksen: So now you connect, if I understand correctly, the criterion of viability with the question of intersubjective validity.

Von Glasersfeld: Right, yes. Especially with regard to the interpretation of older texts, because then we can no longer ask the authors what they really meant. Let me point out, however, that this intersubjective plausibility is also extremely important in the natural sciences. If I develop a new theory about a certain phenomenon, then it will become scientific only when others accept it. Can you remember poor old Alfred Wegener! He designed the brilliant theory of continental drift - but nobody believed him. Only years after his death, and after new observations had become available, the continental drift appeared to be a viable theory to other geologists.

The craving for stability

Poerksen: It is not yet quite clear to me what the criterion of viability primarily refers to: the explanatory power of theories; their capacity for solving problems; the ethical or unethical goals a single scientist or a group of researchers may pursue?

Von Glasersfeld: For me, the question of ethical or unethical goals is more important. However, a theory is fundamentally viable when it solves the problem in hand. Of course, scientists will not - to put it quite naively - give up their work when they are not confronted by urgent problems. There are good reasons for their carrying on: they have learned to appreciate the solving of problems, and so they will create new problems to work on in their imagination - out of curiosity, as it were. I think this is completely justified simply because they can tell themselves that one day the solution they have found for invented problems will enable them to answer those questions more quickly that have become topical in the meantime. This appears to me to be the recursive application of induction: induction means abstracting certain regularities from given experiences. Why do we do that? The reason is that such regularities seem helpful. The invention of theories is something quite similar: their construction was useful in the past - and so it appears sensible to search constantly for new questions and new answers.

Poerksen: Reducing our conversation about truth and viability to a single conclusion, I would say: there is no evidence for an approximation of ontic reality by trial and error.

Von Glasersfeld: Right, yes. And it is this belief, for example, that separates me from Karl Popper with whom I share many ideas otherwise. In Popper’s book Conjectures and Refutations, there is a long and excellent chapter on instrumentalist or pragmatist philosophy, which certainly includes my sort of constructivism. It is exclusively interested in the functioning of theories and models - and not in a piecemeal approximation of truth. At the end of this chapter, Popper wants to show that instrumentalism is philosophically false and detrimental to science. But he does not succeed. He merely asserts his view but fails to provide philosophical proof for it.

Poerksen: But is Popper not right if we argue psychologically? Could we not say that instrumentalism is unsatisfactory because it disregards the fact that the search for truth is a wonderful motive for setting out on a quest that can, as we know from the beginning, never reach its end. Why labour if the conquest of truth is no longer the goal?

Von Glasersfeld: Because something much more important is at stake: surviving on our planet, for instance. As soon as we are born we want to go on living. And the question is how we can manage, despite all the constraints imposed by reality, to get through life in a reasonably satisfactory way. Whether the methods we use are true is completely irrelevant. They must only be good enough to help us reach the goals we have set ourselves.

Poerksen: Still, it cannot be denied that an emphatic, and perhaps admittedly a naive, concept of truth has stimulated human beings in most productive ways in the history of culture and science. Might this suggest that we need the idea of truth as a cognitive motive?

Von Glasersfeld: This is certainly a very tricky question. However, I do not share your view that we need the notion of truth in this connection. I much rather believe that human beings require regularities and the feeling to live in an ordered world; they need to construct causal connections and correlations, which they can project into the future. They want to maintain their stability, at any rate. The mistake is to consider such regularities as truths and to equate them with the understanding and the comprehension of the ontic world. Science and technology rest on the belief that cause-effect relations established in the past will also function in the future. David Hume already made clear that this is a necessary belief that cannot be proved: the world may very well change.

Poerksen: And the sun will not rise tomorrow morning.

Von Glasersfeld: Who can claim to know that with the kind of absolute certainty that reaches beyond past experience? It would be most embarrassing for all of us. Naturally, we hope that the sun will rise again and that we can rely on this in the future. But that is a pious hope.

Poerksen: Are you living in this spirit of fundamental uncertainty?

Von Glasersfeld: As far as everyday life is concerned, it is undoubtedly an advantage to be able to rely on assumed regularities and long-established arrangements. It is not as if I would open the door of my house to check whether the balcony is still there before I step out. I simply take for granted that it has not vanished, I open the door and step out without hesitation. It has worked all right so far - but it is not absolute knowledge.

Sharpening the sense of the possible

Poerksen: What about the sphere of thinking and the system of personal beliefs? Can one live in the awareness here that everything could at any time be different?

Von Glasersfeld: For my part, I think it has enormous advantages to be aware of the relativity of one’s own constructions. Everything becomes easier. Take a trivial example: in the USA, many people believe that one must own a car and a fridge in order to be happy. And one day these people may be upset by the fact that they can no longer afford the car that is supposed to guarantee their life’s happiness. Then such a fixation and rigidity, such one-way thinking, will block other paths and create unhappiness. This is to mean: the constructivist view - at least in my experience - opens up possibilities of existence that previously seemed unthinkable.

Poerksen: The writer Robert Musil, in a similar vein, speaks of the unwritten poem of my own existence and the sharpening of the sense of the possible.

Von Glasersfeld: That is splendid and suits me perfectly. This poem of possibilities must always be kept an open option. Every fixation and decision may mean the elimination of possibilities meriting special consideration. However, it would be foolish to believe that we could simply clear away our beliefs - and then construct the desired and longed-for world at pleasure.

Poerksen: What is the framework within which we may invent ourselves?

Von Glasersfeld: The world is the sum of the constraints impinging on our personalities, our plans, and movements. What manifests itself here is a cybernetic principle: cybernetics does not work - as already pointed out by Gregory Bateson - with causal relations but with constraints. That is the point: we must lead our lives within these constraints, and we should not view our plans to achieve some future goals as the only possibility and try to implement them regardless of the given constraints.

Poerksen: At what point does the world react against the imposition of our constructions? In what moment do the objects scream “No!” when they are to be locked away in a classified drawer of thoughts?

Von Glasersfeld: I would say that it is not a question of objects. The ability to speak of objects presupposes a structure and certain relationships with other objects. What you are calling the world of objects appears to me more like an amorphous whirling that is, however, so multifarious that we are able to create constant models by means of the internal correlation of sensations. Inside us the summing of continual neuronal activities constantly generates combinations of impulses from which we then construct our world.

Poerksen: How can one, from this point of view, distinguish between illusion and reality, right and wrong? How can you do this as a scientist without falling back on the emphatic idea of truth rejected before?

Von Glasersfeld: In everyday life this is rarely a problem. When someone proposes a theory about the mounting of car tyres without the use of a jack, then we can try it out - and I can say to them: “Let’s do it!” In all practical matters viability can, in principle, be established experimentally. The main concern of science is to engineer this kind of proof: a theory is proposed; its utility must be examined; experiments are invented to test it.

Poerksen: This sounds rather unglamorous because all it means is: the constructivist abandons any exaggerated claim to the knowledge of truth - and then carries on as before. The posture revealed by your statements does not seem to do justice to the more or less direct promise of innovation for which constructivism is celebrated today.

Von Glasersfeld: You are referring to the expectations of certain people; they have nothing to do with me. Why should I consider myself responsible for such expectations? Sorry, but this is not my problem. Radical constructivism, for me, is a thoroughly practical and prosaic matter; all it offers is a potentially useful mode of thinking, nothing more. It is most important to keep in mind from the beginning to the end that constructivism, too, is only a model. Whether it is a viable model of thinking or whether it seems practicable to people cannot be determined for everybody and all times; each and every individual must find out for him- or herself.

The linguistic world-view

Poerksen: How did you discover this utility for yourself? Let me speculate: looking at your biography and roughly reconstructing its external stages makes me think that the viability of constructivism and the relativity of reality must have been formative life experiences for you. You grew up in the South Tyrol, studied mathematics in Zurich and Vienna, were a skiing instructor in Australia, a farmer in Ireland, a journalist and translator in Italy, and a professor of cognitive psychology in the USA.

Von Glasersfeld: There is an intimate connection between my life and the constructivist insights - you are quite right there. The mere fact that I grew up with more than one language, that I did not only speak but live in these languages, rendered the idea of one reality problematic. I learned German, English, and Italian in the environment of my childhood. I was taught excellent French in a Swiss boarding school but only learned to understand and really incorporate it when I lived in Paris for a year. It soon struck me that the world was different depending on whether I spoke French, English, German, or Italian.

Poerksen: Do you take the view that every language shapes and structures the experience of reality?

Von Glasersfeld: I think that this thesis must be formulated more prudently and more precisely. Children realise right at the beginning of their lives that they can achieve an enormous amount by uttering sounds, that sounds may be a most powerful instrument. But they also realise that it is very difficult to learn the proper use of this instrument. We are not equipped with a plan at the beginning of our lives that would explain all possible meanings, but we are forced to learn from situations and to explore language by using it. The application of every single word is accompanied by wrong inferences; and only gradually and in a long drawn-out process we are able to patch together the meanings of our own words. And the meaning associated with a sound or a letter finally results from the experiences we make in interactive situations with other speakers. When I live among Italians I am made aware of a particular way of viewing and analysing the world. Sharing experiences with English people at the same time makes me realise immediately that there are marked differences between these two languages. The Italians and the English may both believe that their languages represent the world in the appropriate way. Living between these two languages and worlds, as I do, I can only affirm the insurmountable subjectivity of word meanings and point out the characteristic difference in the representations of reality. From this experience of my life stems my interest in what is called reality.

Poerksen: Could you quote an example illustrating the diversity of world views underlying their linguistic representations?

Von Glasersfeld: Just think of prepositions and the characteristic relationships they can generate within a language. Translating a couple of sentences from English into German, for instance, may involve the proper rendering of conceptual relationships expressed by prepositions. And then we notice immediately that these two languages, which are not very far apart historically, do not match. The German preposition in includes at least 30 spatial, temporal, and modal relations. The English in is no less powerful but some of the relations it represents are different. (I say it in English becomes “Ich sage es auf deutsch”; in my place becomes “an meiner Stelle”; in this way becomes “auf diese Weise” etc.). Consider how often prepositions like in, on, after, over etc. are used, and how important they are because they constitute relationships between objects and situations, and you will realise that there are all sorts of relations and loose associations in a language, which do not match those in another.

Poerksen: What you have presented nicely illustrates the so-called “linguistic relativity principle” formulated by Benjamin Lee Whorf in his famous article Linguistics as an exact science. He wrote: “... users of markedly different grammars are pointed by their grammars toward different types of observations and different evaluations of externally similar acts of observation, and hence are not equivalent as observers but must arrive at somewhat different views of the world.”

Von Glasersfeld: Exactly, that is quite correct. The diversity of the perceptions of reality is what one experiences when living in more than one language. Here is a little story about a relevant experience of mine. A friend from England once visited me in Milan. We went on an excursion and wandered along a river when we reached a spot where the railway line joined the river. In the meadow near the riverbank, quite close to the rail track, an Italian family was sitting enjoying a picnic. Suddenly we heard the distant rumble of the approaching train; the mother jumped up and shouted: “Attenti bambini, arriva il treno.” My English friend turned to me: “What did she say?” And I realised that I could not simply give a literal translation of this sentence; it had to be: “Be careful, children, the train is coming” - and not: “Be careful, children, the train is arriving.” The reason is that the verb to arrive presupposes a stationary element; the train must stop. In Italian, you can use arrivare to express that something is in the process of approaching.

Poerksen: Becoming aware of this fundamental diversity in the meanings of expressions and realising that even in one single language different group-specific semantic systems exist side by side, the communicative situations we have to take into account appear most complicated. The question is then: What does it mean to understand an utterance if the meanings of expressions, as you maintain, are essentially subjective and differ from language to language?

Von Glasersfeld: In my view, it is impossible to expect that a person’s utterance activates precisely the same thoughts and conceptual networks that the person originally associated with it. This is to say: transmission, message, and receiver are misleading metaphors with respect to conceptual content. Communication is never transport. What moves from one human being to another are sounds, graphic figures or, as in telegraphy, electric impulses - in brief, oscillating patterns of sound, light or electricity. And we can only assign meanings to these energy changes in terms of our own linguistic experiences. Ever so often we speak with people and realise two or three days later that they have not understood at all what we meant to say or thought we said.

Poerksen: We never know whether we understand each other?

Von Glasersfeld: No, we can never be sure because there is no possibility of control and inspection. I can never really know what goes on in somebody else’s head; I can only go by what they say - and what generates certain ideas in my head that are themselves the products of individual and subjective experiences. The feeling of understanding results, I think, because the other person does not do or say anything that might indicate an incorrect interpretation on my part.

Poerksen: Does this mean that we recognise failed communication only when we in fact notice that we quite definitely do not understand each other?

Von Glasersfeld: That is how it is. That we failed to understand each other I can only effectively ascertain when the other person says or does something that is, in my view, incompatible with what I said. However, the fact that societies and environments are comparatively similar justifies our expectation that the people we talk to understand the words that we use in a similar way or at least interpret them in a way that does not contradict our own interpretations. Consequently, the vagueness of the meanings of expressions is significantly restricted.

The end of instruction

Poerksen: During the last few years, you have published a great number of articles dealing with the principles of constructivist didactics. Your reflections on the act of understanding and the viability of constructivism are a good point of departure, I think, to illustrate the practical import of your thinking with reference to the field of education. Let me put the question quite generally: What consequences for schools can be derived from your epistemological considerations?

Von Glasersfeld: The first consequence from what has been said so far is nearly trivial: language cannot be used to transfer conceptual content; all conceptual content must be constructed by the students themselves. The compulsion to learn things by rote, constant repetition, and other forms of dressage cannot guarantee understanding.

Poerksen: Are not the favourable school reports, which the children bring home, an indication that they have understood what they were taught?

Von Glasersfeld: Well, we simply need good reports and good marks in order to be upgraded. But they are, of course, not unambiguous indicators of students’ understanding of a subject, of whether, for example, they are really capable of applying some formula from physics. Despite good marks, they often lack the insight into how the conceptual connections between the symbols in a formula must be understood.

Poerksen: What other insights can constructivism supply for education?

Von Glasersfeld: From a constructivist point of view, it seems most important to me to take students seriously as intelligent beings capable of independent thinking, that is to say, as beings that construct their own reality. Students are neither idiots nor victims to be filled with knowledge. The respect I am demanding here is justified by the fact that it is the students who, in the process of learning, construct knowledge actively and on the basis of what they already know. It is therefore indispensable, I believe, that teachers build up at least approximate images of what goes on in the minds of their students; in this way only, they will stand a chance of changing something there. This means that everything children say and do must be taken seriously as an expression of their thinking.

Poerksen: Even when children utter patently meaningless or incorrect things?

Von Glasersfeld: Most children’s utterances are not at all meaningless - they are only incomprehensible to us adults, at first. We must ask ourselves: Why is this or that utterance meaningful for the child? How is that possible? - The “mistakes” of students are, therefore, of enormous importance: they provide insights into their thinking, and they offer decisive hints for the creation of new situations in which the faulty solutions and methods of the children will no longer work. This is the best way for inducing what Jean Piaget called accommodation: if the results of one’s actions do not match one’s expectations, then learning can begin.

Poerksen: Listening to what you are saying makes me understand one of the inspired exaggerations voiced by the communication scientist Gordon Pask: he proposes that the students become the teachers. Teachers have to learn from students what the students do not know and why they have difficulties to grasp and apply what they are told.

Von Glasersfeld: The statement by Gordon Pask that you quote is not too much of an exaggeration. In middle school, at the latest, teachers can really learn from their students because the students may hit upon ideas unknown to the teachers. Some of the children with whom I worked in mathematics classes managed to invent clever methods of subtraction that, however, functioned only in the precisely delimited area of the problem configuration in hand. They could not be generalised. Nevertheless, it is quite conceivable that teachers can profit enormously from students; they may get to know tricks that students have managed to contrive because they have perceived their tasks from an unprejudiced point of view.

Poerksen: For many people, however, the static culture of instruction, which secures the maximal authority of the teachers, is definitely more attractive.

Von Glasersfeld: Go and talk to teachers who have been teaching for 15 or 20 years. Of course, I do not know the situation in Germany, but in the USA you will encounter many soured and desperate people who know that what they are doing does not work. Whenever teachers are successfully brought to observe constructivist methods in their schools and really attend to them, they are forced to acknowledge that something different and something new is happening there: the children become active; they even show signs of pleasure; they enjoy their time in class because there is no fixed curriculum; and they love doing something when they are not compelled to do it.

Poerksen: But this different manner of teaching would possibly use up too much time, time that simply is not available. Some teachers probably fear that the children - if dealt with according to these ideas - would not learn enough of all that which they simply have to learn, too.

Von Glasersfeld: It is the job of teachers to be patient. Naturally, adapting to constructivistically inspired teaching will cost time, but applying these considerations continually will often produce something astonishing. It may happen that children approach their teachers after class and ask for further tasks. Manners begin to change; children realise that it is enjoyable and satisfying to solve problems. Fortunately, there are now quite a few empirical investigations that confirm the success of constructivist methods in mathematics teaching. They show that children at the end of their first year are just about equally good as the children taught in the conventional way. At the end of the second year they are better, statistically. And in their third year it becomes apparent that they have learnt how to learn: they are now superior to their contemporaries also in other subjects because their whole attitude towards school and the taught subjects has changed.

Poerksen: The constructivist premise of the impossibility of absolute truth also implies, it seems to me, the teaching of even the hard sciences as historical disciplines. In concrete terms: mention Democritus when talking about atoms, Faraday in connection with electricity, and link optical phenomena with the historical ideas about vision and visual perception that reach back into antiquity. And so on. Students would always, in a more or less direct way, be enlightened about the historical conditions of the origin and the relativity of what passes for knowledge.

Von Glasersfeld: A wonderful idea that, however, meets with aggressive resistance from certain quarters. I have often spoken at conferences of the International Association of the History and Philosophy of Science in Science Teaching; the relativisation of scientific knowledge appeared to many teachers who were attending these conferences, an intolerable idea that undermined their position of authority. I would therefore recommend that these teachers no longer base their authority on the quantity of apparently objective knowledge but on their capability and experience in solving problems together with their students. What must be thrown out unconditionally is the notion that teachers are omniscient. This is my recommendation.

From outsider philosophy to fashion

Poerksen: Leaving questions of education again and surveying the whole situation of constructivism we cannot fail to notice that, from the perspective of the history of knowledge, constructivism has entered an explosive phase. It is in the process of being transformed from an outsider philosophy into a fashion, and in certain publications it even assumes the traits of a weltanschauung. Did you ever expect this kind of popularisation and transformation of your ideas?

Von Glasersfeld: Not in my wildest dreams would I have thought that constructivism would be received in this way. The possibility of a transformation of these ideas into an intellectual fashion never occurred to me; but there is nothing one can do about it. What people do with certain ideas is their business. True enough, an uncanny number of people call themselves constructivists today. At home there are many who have no idea whatever of the basic tenets of constructivism. My only hope is that these ideas will open up a more advantageous view of the world for some people. And this hope outweighs the misunderstandings, the trappings of fashion, and the innumerable abounding misconceptions. They seem to me less important.

Poerksen: In what ways is constructivism helpful for you personally? Can it possibly prepare for the inevitability of disease and pain?

Von Glasersfeld: But of course. Perhaps I am a bit naive in this regard but constructivism has made many things clear to me. If I can, in principle, never truly know the reality beyond the experiential world of my life, then it is meaningless to worry about what may happen or perhaps not happen when my time in this experiential world is ending. It seems totally meaningless to me to be afraid of death; I am afraid of pain, of falling over and fracturing my bones. It happened last year, and it was painful; but that is something entirely different. And it is certainly imaginable that I will be struck by sentimental feelings of nostalgia one day, when I have to accept that I cannot cultivate my habits any more. But I do not know how I came into my world; I do know that my time in this world is limited. Why should I worry?