4: Truth is what works

Francisco J. Varela on cognitive science, Buddhism, the inseparability of subject and object, and the exaggerations of constructivism

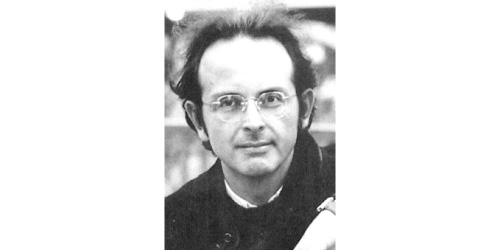

Francisco J. Varela (1946-2001) studied biology in Santiago de Chile, obtained his doctorate 1970 at Harvard University with a thesis on the insect eye, and worked there for some time in the laboratory of Torsten Wiesel, the later Nobel Laureate for medicine. From his scientific beginnings as a researcher in biology, he did not only study and practise biology but, resisting the dominating mainstream, pursued a research programme that ignored and broke down traditional disciplinary boundaries. This research programme is best characterised as experimental epistemology, a concept introduced by the neuropsychiatrist and cybernetician Warren S. McCulloch. Varela’s great aspiration was to examine and answer the philosophical ur-question of cognition with scientific precision and with the help of the best possible theoretical framework.

Having obtained his doctorate, he went back to Chile to work as a professor of biology together with Humberto R. Maturana. He contributed to the writing of the theory of autopoiesis which was to cause a furore in the world of science as a universally applicable explanatory model. After the overthrow of Allende and the installation of the dictatorship by the putsch general Pinochet, Varela first escaped to Costa Rica, then became professor at the American universities of Colorado and New York, and finally returned in 1980 to the University of Chile in Santiago for five years. Temporary positions as guest professor for neurobiology, philosophy, and cognitive science in Germany, Switzerland and France led him to Paris, in the end, where he worked as a research director of the Centre National de Recherche Scientifique until his death on 28 May 2001.

In his research work embracing cognitive science, evolutionary theory, and immunology, Varela, constantly inspired by his fundamental interest in the key questions of epistemology, gave the epistemological debate a new orientation. In his thinking, he refuses to accept the strict separation of subject and object, of knower and known, which as a rule unites realists and constructivists alike. Varela rejects the fundamental dualism dividing mind and world, which had shaped Western philosophy from its earliest beginnings. He does not subscribe to the idea that human individuals can invent their own realities blindly and arbitrarily, and without experiencing any resistance from the external world and all other things given. He equally distances himself, however, from the diametrically opposite position that overstates the inherent power of the world of objects. The external world and all other things given cannot determine what happens in an organism. Francisco J. Varela’s claim is that individual and world create each other.

The computational model of the mind

Poerksen: The ancient key questions of philosophy are at the centre of modern cognitive science. What is the essence of the mind? Do our conceptions represent a given world, which is independent from our minds? What is the formative power of external objects over our perceptions? How does cognition function? The search for an adequate answer and an improved understanding of the human mind has led many cognitive scientists to entertain the assumption that the brain is actually a kind of computer. Memory is taken to be a store. Thinking and perceiving are understood as data processing in the sense that an independent external world is computationally transformed into symbols and represented in the organism in this manner. You are very critical of this view. Why?

Varela: If the brain is considered as a kind of computer then cognitive research is limited to discovering certain self-sufficient shapes - the symbols - together with the rules governing them - the programs. But this search for symbols and programs will never be profitable because it simply does not do justice to the way the brain functions. There are no symbols to be discovered in the brain; the brain is not based on software; objects or human beings are definitely not represented by way of symbols in the brain, although even most intelligent people once believed this to be so. So there is little point in searching for neuron number 25, which is supposed to represent my grandmother or some other part of the world. The brain is essentially a dynamically organised system; numerous interdependent variables have to be taken into account, which can only be dissociated from each other in an arbitrary way.

Poerksen: You are critical of the research programme based on the identification of brain and computer.

Varela: Not only that; my criticism has not only empirical but also epistemological foundations. Alone common sense finds no difficulty in understanding that living beings necessarily manifest themselves in particular actions and in their appropriate environments. The actions of an animal and the world in which it performs these actions are inseparably connected. Going through life as a small fly makes a cup of tea appear like an ocean of liquid; an elephant, however, will see the same amount of tea as an insignificant drop, tiny and barely noticeable. What is perceived appears inseparably connected with the actions and the way of life of an organism: cognition is, as I would claim, the bringing forth of a world, it is embodied action. Whoever, on the contrary, believes in the computer model of the mind, inevitably believes in the existence of a stable world independent from living beings. This world is recognised by living beings and represented in their nervous systems in the form of little symbols; cognition, according to this view, is a kind of computation on the basis of symbols.

Poerksen: I suppose that such a view also implies a naive kind of realism: one believes in static, given world that is represented in our cognitive apparatus.

Varela: Not necessarily. Not every cognitivist or scientist following such a model is necessarily a naive realist. The key concept rests on two central premises that admit of different epistemological interpretations. On the one hand, cognition is assumed to be essentially a form of symbol processing, which resembles the functioning of a computer. Such a conception accords with scientists of both a realist and a non-realist orientation alike. On the other hand, the relation between the cognitive system and the world is, in the classical sense, seen as a relation of semantic representation: the mind processes symbols, which represent the properties of the world in a specific way. This idea of a fundamental semantic correspondence between symbol and world is also open to interpretations that need not necessarily be realistic.

Poerksen: But surely, anyone claiming that there is some sort of correspondence between world and symbol is inevitably a realist.

Symbol and world

Varela: No, because we could say that there is a specific relation and a semantic correspondence between the word table and the object that we call a table. A relativist and critic of realism favouring this view would then add, for instance, that the relation between symbol and world is obviously different for an Eskimo and for a pygmy, and that they have different words, i.e. different symbols, for what we usually call a table. So even a relativist can uphold the notion of semantic correspondence.

Poerksen: Why did the computer model remain attractive for so long? It seems to me that it promised the more or less imminent explanation of brain and mind. Taking the computer as the archetype of cognition generates clearly defined research objectives, unambiguous questions, and justified hopes for success.

Varela: Exactly. I am not at all surprised by the appeal of this model because it matches common ideas and is an expression of our craving for transparency. It is deeply rooted in the rationalist traditions of the West and supported by them. The idea of representation in the form of symbols has long been the foundation of mathematics and the basis of linguistics, whereas the ideas that I pursue introduce something very novel. There is still less experience with the investigation of dynamic and emergent systems, everything becomes more complicated and less easy to penetrate. Cognition is the bringing forth of a world; the meaning of something is no longer understood as resulting from a correspondence between an object and a symbol but as the emergence of stable impressions and patterns - invariants. These develop in the course of time. A regular pattern must have appeared first before we can take it to be a feature of a world that we consider independent from us.

Poerksen: You have published numerous studies on colour perception. How does a stable colour impression come about? How do animals or humans perceive colour?

Varela: Look here, there is a book on the table in front of us. Due to our essentially identical structure it appears in a colour that we call green. We human beings are the products of an evolutionary lineage along which our ancestors developed specific patterns through their encounters with the environments in which they found themselves. If we now assume that our given world and some object that we call a book have particular properties, and if we take into account the history of our descent, then these two factors yield a mutually determining invariant pattern. Both of us call this pattern a colour and name this colour green. But we have known for a long time now that birds, for example - due to their evolutionary history - perceive something that we simply cannot imagine: numerous birds seem to have a colour system comprising four basic colours whereas three are sufficient for us humans.

Organisms exist in different perceptual worlds, they live in different spaces of chromatic invariants. So the question arises: what does this book look like? Who is right? The birds or we? The answer is: both. These different perceptions permit both birds and humans to stay alive. The meaning of an object, its colour or its properties, emerges through long phases of coupling between organism and world. A colour is not the result of a construction taking place exclusively within the organism, nor does it exist - the other extreme - in itself and independently from the living being that perceives something. We are faced by stable qualities that can only develop on the basis of an evolutionary history. They cannot be assigned unequivocally to either the knower or the known, they cannot be clearly attributed to either the subject or the object.

Poerksen: What you call the bringing forth of a world, related thinkers simply designate the construction of reality. The difference between these two concepts is, for me, that constructivists have traditionally foregrounded the subject part. You seem to plead for a more balanced view of the relationship between subject and object. You insist: there must be both; both are indispensable for the act of cognition.

Varela: That is the central idea. Only the co-construction of subject and object can overcome the traditional logical geography of the strict separation of knower and known, internal and external world. There is no subject, as the constructivists suggest, on one side, constructing its reality in the desired way. And there exists no object, as the realists believe, on the other side, which determines what happens in the organism. My view is that subject and object determine and condition each other, that knower and known arise in mutual dependence, that we neither represent an external world inside nor blindly and arbitrarily construct such a world and project it outside. My plea is for a middle way that avoids both the extremes of subjectivism and idealism, and the presumptions of realism and objectivism.

The philosophical problem factory

Poerksen: Perhaps two aphorisms by Heinz von Foerster could contribute to further clarification. He epitomises the central idea of realism with the words: “The world is the cause, experience the consequence.” The fundamental principle of constructivism is, however: “Experience is the cause, the world the consequence.”

Varela: I do not agree with either position. As one printed version of this conversation is intended for a German audience, I should like to state quite clearly and unambiguously: I am not a realist, and I do not consider myself a constructivist, however often I may be classified as such in Germany. Classical constructivism does not at all impress me as a convincing mode of thought because it posits one side of the cognitive process as absolute: the organism forces its own logic and its own models on the world. I do not believe that to be the case at all. Such an assumption appears to me to be a relapse into neo-Kantian thinking. I have been trying for years to keep my name out of this debate - but obviously I have not been very successful.

Poerksen: To repeat the question: when confronted by the distinction between subject and object, you refuse to side with one or the other?

Varela: The goal of my work in cognitive science is not the dialectical negation of one side or the other. My question is not whether the world is represented in the organism, whether the subject is primary or whether the decisive influence is due to an object, my point is the total abolition of both extreme positions, not their affirmation or negation. My point is that neither the subject nor the object is primary. Both exist only in mutual dependence and in mutual determination.

Poerksen: If you are unable to make this decision, how can you define a clear epistemological stance?

Varela: Why do I need the decision for subject or object in order to do epistemological research, to formulate hypotheses and design research projects? The task of epistemological thought and research efforts is the question of how we can understand the way knowledge comes about and how conceptions of reality arise. The decision for subject or object already contains a definition of cognition and knowledge although that is, in fact, the problem to be solved.

Poerksen: We could argue, however, that the distinction between subject and object is the central philosophical problem factory. Those who put the object first, investigate the world - and its impingement on the subject; they practise object-centred philosophy. Those who hold the subject to be primary, analyse its peculiarities, its features, its logic. They neglect objects and practise subject-centred philosophy.

Varela: I insist: the view that an epistemologist is compelled to distinguish between subject and object in order to study the relation between the two is the heritage of Western rationalism and the Kantian theory of knowledge. This view is historically conditioned. I am sorry but I really do not want to play this game because philosophical conceptions have been available for a long time that evade this alleged coercion into dualism. The phenomenologists Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty have shown clearly that an inevitable and inseparable connection exists between what might be called a subject or an object. They are not opposites.

Poerksen: But the early studies of the phenomenologists that you incorporate in your work in cognitive science, are of a realist orientation. Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology, already formulated the battle cry destined to become famous: “Zu den Sachen selbst!” [“To the objects themselves!”] Is that not the research programme of a realist, a turn in the direction of the object?

Varela: It is, in my opinion, one of the amusing puzzles how little Edmund Husserl, whom I value as the greatest philosopher of the 20th century, is understood in his own country, and how incredibly he is turned into a caricature of himself in German universities. What Husserl means when he speaks of the need to turn to the objects themselves, is not realism at all, definitely not. He is not concerned with something already existing in a given way. The purpose of his phenomenological work is to examine, without premature judgment, the perceptions of things and objects that appear to be given. This is precisely the programme of phenomenology that is of such crucial importance to modern cognitive science: to investigate, without prejudice and rash judgment, our experiences and perceptions, to include ourselves as scientists in our reflections, in order to avoid any disembodied, purely abstract, analysis.

Poerksen: But if we, as you suggest, begin with our perceptions and experiences, we immediately see: there is a subject and an object. Both appear separated. That is the fundamental insight we gain. It should actually lead us back to realism again.

Varela: You are now speaking of common, everyday experience, which is formed and shaped by a whole set of theories and metaphysical presumptions. I do not propose to trust that kind of experience. On the contrary, it is the very duty of philosophy and natural science to question and challenge ordinary perception and everything that seems self-evident, and to confront it with new approaches. These may contradict common sense but that is no problem for me at all and quite irrelevant; the crucial question is whether they fit, whether they are true. The reference to common sense does not prove anything.

Poerksen: What do you mean by “fitting,” “true” approaches? If truth is the goal of your researches, then you definitely assume a realist position, after all. Of course, there are people who believe that we could keep truth as a kind of ideal and a distant goal because we can never do more than approximate it step by step, anyway. But that thesis seems contradictory to me, too. If we want to establish whether we have achieved some partial understanding of the absolute or come closer to the truth, we must be able to compare our partial understanding with absolute truth itself. However, this comparison of realities presupposes the possibility of apprehending absolute truth - otherwise the claim of its approximation remains undecidable. My thesis is that we can only maintain the idea of truth as a goal of human knowing, however distant, if we assume an extreme realist position at the same time.

From necessity to possibility

Varela: The attempt to characterise my position as clandestine realism and a masked belief in truth is due to the definitional decision you have taken, which I certainly do not accept. You are working with a concept of truth that is based on correspondence: truth is the correspondence between theory and reality. Such a position will inevitably make you a realist. Let me just point out that there are many ways of speaking about truth. My own concept of truth, which is inspired by phenomenology and the philosophy of pragmatism, is best understood as a theory of coherence: what counts is the consistency of theories, the coherence of viewpoints. Truth is, the motto of pragmatism proclaims, what works.

Poerksen: What, then, is false?

Varela: In a pragmatist sense, something can be false only, to put it very bluntly, if it kills you. Everything that works is true. Reconsider the example of colour perception. Birds and humans experience coloured objects; their different truths, however, are not due to a correspondence between their views of reality and reality itself, but to the mutual determination of subject and object. The perceptions of birds and humans and innumerable other living beings are all viable because they allow the continuous coupling with the world. If an organism does not develop a consistent capability of moving in a coloured world, it will, in the worst event, disappear from this earth. The species will die out.

Poerksen: But there are so infinitely many, totally contradictory, perceptions and theories that simply work and that do not kill us! Deadly failure as the criterion of falsification is a bit too vague for me.

Varela: This vagueness and the fact of lacking consent are no problem at all. All this conforms exactly with scientific practice. In contradistinction to the prejudices of some people, scientific truth does not consist in the correspondence between theory and reality. Scientific knowledge is inevitably related to the surrounding circumstances of the social world and - between virtual quotes - the reality. Every single object of scientific research is, as Bruno Latour used to say, a mixed object: it is social and it is real, it is real and it is social. When someone develops theories about DNA, black holes, or the weather, then these theories must be discussed - irrespective of any hope of absolutely valid justification and ultimate security. Then other people possibly develop contrary conceptions. So we try hard to find out which of the hypotheses work better and who has the more convincing arguments. And one day new and completely different considerations and theories enter the debate.

Poerksen: Pursuing the idea of ultimate failure and final falsification a little further, we might say: the loss of life in a final conflict with the real world tells us that our assumptions were wrong. In a similar vein, Warren S. McCulloch, one of the father figures of cybernetics, once said that the acme of knowledge was to have proved a hypothesis wrong.

Varela: I would never talk like that simply for aesthetic reasons because the central images of such formulations are conflict and struggle. When I explain that individual organisms bring forth their world, and that all the different views of the world are equally true and viable, conflict and struggle lose their importance. Falsification is no longer the central concern of scientific work. There arises a panorama of coexistence, a dialogical space in the world and in science. We can find joy and fun in comparing the plethora of possible forms of existence and the diversity of views and assumptions, we can develop ideas, exchange and debate them. Absolute reality, in my eyes, does not dictate the laws we have to obey. It is the patricharchal perspective to proclaim the truth and to decree absolutely valid rules that constrain, limit, and eradicate opportunities. What might be called absolute reality, tends to appear to me as a feminine matrix, whose fundamental quality is the opening up of possibilities.

Poerksen: What is not impossible is possible?

Varela: Exactly. And what is not prohibited is permitted. There are natural limits but there is no densely woven, blocking, and stifling system of rules. This is the soft and space-creating quality of a feminine matrix.

Poerksen: Can you reconstruct how you broke through to this different understanding of cognition and life processes? What inspired your criticism of conventional scientific practice, of mainstream cognitive science, and of classical epistemology?

Varela: When I was studying at Harvard as a young man and writing my thesis, I felt dissatisfied with the prevailing discourse of representationism, with the computational model of mind, and with the dominant epistemology. Why? I am not really sure myself. At the beginning, it was probably more of a feeling that something was wrong. One reason may have been that I came from another country with a different culture and, therefore, never really belonged; in addition, I had not been educated in the standard US way. It helped, I suppose, that I really came to the USA from another planet.

Poerksen: You are referring to Chile?

Varela: Not only that; I spent my early childhood with my family in a small village in the mountains where everything I had was the sky and the animals. Life there had barely changed since the 18th century. At some later stage, I went to school in the big city, without ever forgetting about my roots, and finally won a doctoral scholarship for Harvard, one of the centres of the scientific world. The lack of belonging and the feeling of estrangement have accompanied me since the days of my birth. To appear a little odd somehow and to feel somewhat peculiar, is natural for me and provides, so it seems, quite a good platform for new discoveries and for perceptions that may seem perplexing at first. When I began to present my own views, to expose them to critical debate and to defend them, my feeling of marginalisation returned in different form. I felt myself easily excluded, appeared as a weird character to the scientific establishment, as someone who could not quite be trusted. But then I had the good fortune to meet people with whom a harmonious relationship was possible, and slowly my own perspective gained stability until it finally became part and parcel of my personality.

The theory of emergence

Poerksen: Your search for new and unfamiliar perspectives has led you, as one of your most recent books shows (The Embodied Mind: Cognitive science and human experience), to combine not only American cognitive science and European phenomenology, but also to unite these two disciplines with a philosophy from the East - Buddhism - to create a new theory and a new research programme.

Varela: This combination and connection is, in no way, arbitrary or a result of personal predilection only; it is a central part of my work as a cognitive scientist. The question is for me why Buddhism should be so interesting to a phenomenologically oriented theory of cognition that treats the bringing forth of worlds. The reason is that there is, at present, a deep rift between natural science and the world of immediate experience that urgently needs to be bridged - particularly with regard to cognition. What is an investigation of our minds worth if it does not even touch on living, embodied experience? What is the point of abstract and disembodied reflection that separates body and mind into different objects of inquiry? Now it so happens that Buddhism is in itself a practically oriented, non-Western phenomenology offering a precise analysis of what human beings may experience, which is analogous to the central research results of cognitive science. It supplements, inspires, and supports the experimental approach. Buddhism - sustained by qualified techniques of self-examination - trains reflection that may be re-enacted in one’s own experience and deals, amongst other things, with the essence of mind, the notion of the self, and the concept of a static and localisable identity. The weakness of Husserlean phenomenology and its central orientation towards experience is that it lacks a well-described and directly applicable method to examine experience: the techniques of Buddhist meditation as practised for 2500 years include such a method. This is the reason for uniting Buddhism with phenomenology and cognitive science.

Poerksen: How are we to understand that? Are you suggesting that cognitive scientists ought to meditate? It is hardly imaginable that the offensively rationalist science scene would accept such a proposal.

Varela: I do not care whether people practise Buddhist meditation or not. Nor am I advocating a combination of Eastern and Western thinking of whatever kind; my goal is quite simply and clearly to perform successful research. And that is why I think that all good cognitive scientists, who want to understand the mind, have to deal with the specific investigation and analysis of their own experiences and to include themselves in their reflection, in order to avoid the disembodied, abstract form of description of some ethereal mind that does not carry us forward. This study of human experience, which is gradually moving into the centre of cognitive science and is accompanied by a real boom of the investigation of the mind, requires knowledge, training, and a method; Buddhism supplies this method. Running around in gardens does not make people botanists; listening to sounds does not make people musicians; looking at colours does not make people painters. And in quite the same way, cognitive scientists who want to focus on the analysis of their own experiences and the study of the mind, must first be taught to be experts. They need means and methods to overcome their ordinary sense of reality, to experience immediately the perpetual activity of the mind, and to restrain its unceasing restlessness. The Buddhist techniques of meditation lead to experiences and insights that would be unthinkable without such methodical schooling.

Poerksen: One of the central goals of Buddhist meditation is to realise that the ego or the self - understood as some stable, localisable, and autonomous instance of control, which governs our decisions - does not exist. This very thought, however, contradicts the standard conceptions of people socialised in the West; they much rather seek the strengthening and stabilisation of their individuality. Will this not lead to a new rift between Buddhist notions and Western experiences? In other words: can cognitive science really be combined with this key idea of Buddhism?

Varela: Naturally, the ordinary mind will have great difficulty in even comprehending the idea of self-lessness. Its experience is, however, the consequence of disciplined practice, not the result of a superficial analysis of the personal self. Of course, we all assume, as a rule, that there is a stable and undoubtedly even localisable self, and that this self is the actual foundation of all our thoughts, perceptions, and actions. We believe in our identity and therefore presume a firm basis on which we stand and from which we act. When, however, the purported existence of this autonomous self is questioned, then Buddhist experience and the insights of cognitive science resemble and supplement each other. Concerning this specific question, in particular, there is no gap at all between the insights reached through meditation and the research results of cognitive science. Both arrive at the identical conclusion that an independent self cannot be detected and that the search for it inevitably leads us astray.

Poerksen: If there is no such thing as an unambiguously localisable self, how do you explain the phenomenon that we are all convinced of possessing a stable identity and an unchangeable essence?

Varela: One of the most important scientific discoveries of the 20th century is that locally interacting components, if subjected to certain required rules, can produce a globally emerging pattern - a new dimension of identity, another level of being - that optimally satisfies a certain function. This transition from locally effective rules to globally emerging patterns enables us to explain numerous different phenomena that would otherwise remain totally mysterious and impenetrable. All of a sudden, we have - within the framework of the theory of complexity and with the concept of the dynamic system - a universal key to unlock the brain, a tornado, an insect colony, an animal population, and ultimately the experience of the self. Why is the idea of an emergent pattern so interesting? Consider, for example, a colony of ants. It is perfectly clear that the local rules manifest themselves in the interaction of innumerable individual ants. At the same time, it is equally clear that the whole anthill, on a global level, has an identity of its own: it needs space, it occupies space, it may disturb or obstruct the activities of human beings. We can now ask ourselves where this insect colony is located. Where is it? If you stick your hand into the anthill, you will only be able to grasp a number of ants, i.e. the incorporation of local rules. Furthermore, you will realise that a central control unit cannot be localised anywhere because it does not have an independent identity but a relational one. The ants exist as such but their mutual relations produce an emergent identity that is quite real and amenable to direct experience. This mode of existence was unknown before: on the one hand, we perceive a compact identity, on the other, we recognise that it has no determinable substance, no localisable essential core.

Security in insecurity

Poerksen: So the self of a human being would be, for you, an emergent pattern, too?

Varela: Exactly. This is one of the key ideas and a stroke of genius in today’s cognitive science. There are the different functions and components that combine and together produce a transient, non-localisable, relationally formed self, which nevertheless manifests itself as a perceivable entity. We can greet this self, give it a name, interact with it in a predictable way, but we will never discover a neuron, a soul, or some core essence that constitutes the emergent self of a Francisco Varela or some other person. Any attempt to extricate a substance of this kind is misleading and bound to fail as both cognitive science and Buddhism demonstrate.

Poerksen: What are the implications of these ideas for classical ethics where the essentialist autonomous self is invoked as the addressee of the demands of the good and the beautiful? We might claim that giving up the idea of the autonomous self robs ethics of its foundations. Unexpectedly, the actor has gone missing. The autonomous, reflecting actor dissolves into emergent patterns.

Varela: This point of view derives, of course, from the Western conception that an autonomous individual is the prerequisite of an ethical relation. You envisage an individual that interacts with another individual in an ethical or an unethical way. I do not share the premises underlying this view; they are not at all convincing and they do not accord with the latest research results and the empirical data that support the idea that the mind is not a singular phenomenon but an intersubjective one. Recent data from child development research show that the very first actions of children are not primarily intended to strengthen the individual personality but always serve to build up relationships with other people. We develop our self precisely to the extent that other people have already attained such a self; the reflection in the other makes the other’s awareness our own awareness. The situation manifesting itself here recalls the relations between organism and environment, subject and object. There is mutual determination; we cannot say who or what was first. This means: the view that the mind of an ethical actor is anchored somewhere inside that individual contradicts empirical data. The mind that we ascribe to an individual is, in a most interesting sense, already of a collective, intersubjective nature. What we are, as numerous experiments with primates and also diverse neurobiological results show, is to the same extent individual and non-individual: it belongs to the sphere of intersubjectivity.

Poerksen: Marvin Minsky, too, in his book Mentopolis, throws out the self with the help of arguments from cognitive science, but then goes on to say that we should nevertheless hold on to the essentialist idea of an autonomous self: we must, he writes, decide in favour of this self in order to safeguard the conceptual foundation of ethical behaviour.

Varela: In response to this I can only exclaim: what utter nonsense, what inane waffle! This is definitely the worst ever written by Marvin Minsky. Can you imagine that your own ethics and your relevant moral principles are based on decisions?

Poerksen: Of course I can. Whoever acts ethically, decides, and chooses between good and bad. And this very act of choice presupposes an autonomous and stable personal self.

Varela: To my mind, such a plea for an ethics based on decisions seems absurd because I believe that my own moral principles should be based on truths that can be experienced and re-enacted. An ethics of apparently rational decisions is highly problematic both for pragmatic and aesthetic reasons; it lacks power to convince, and it seduces to moral preaching. The decision to believe something and then to act accordingly is arbitrary and unconvincing for others. It is without foundation, and it is no possible basis for ethical behaviour. However, if I take the assumption, which is self-evident, that every self is intersubjective by its very nature, as my point of departure, then ethics acquires a new basis that is no less liberating. There is then no longer any need to preach and observe commonplace moral principles, to proclaim some know-what, to demand rational justification or follow an imperative, but it is important to develop an understanding of non-moralist ethics together with the know-how of learning how to cope with situations in a spontaneous and immediate way.

Poerksen: I do not agree. If my choice between good and evil is usurped by some experiential truth of whatever kind, then every possibility of acting in a responsible way is gone. Everything is decided, everything is pre-ordained; all I can do is to endorse my truth and my scientific view of the world according to design. Ethics, in my view, presupposes the freedom and the necessity of choice - and choice requires responsibility. Basing my ethics on some truth, however, destroys all my interactive spaces with their openings in both good and bad directions.

An ethics of spontaneous goodness

Varela: What can I say? You cannot seriously imply that my conception of truth is a sort of fundamentalist weltanschauung, justified in some way or other. For me, truth involves the radical and maximally unbiassed observation of personal experience; it is the result of Buddhist practice, phenomenological studies, and scientific research. It is nothing final, it is not fixed for all time, but it provides a justification for my reflections of ethical questions. If our point of departure is a kind of non-essentialist identity and the intersubjective nature of human existence, then ethics can be justified in a meaningful way supported by human experience. The continual practice of self-exploration, the discovery of self-lessness and the intersubjective nature of human existence, according to the ethical tradition of Buddhism, lead to behaviour inspired by care and compassion for the fellow being. Opening your eyes will enable you to walk on without stumbling. Exploring yourself and gradually building up your understanding of self-lessness and non-individuality will enable you to make out the goal of the cultivation of the experience of interdependence. And the condition of the fellow being will turn into a matter of direct personal concern.

Poerksen: If I understand you correctly, then what you are proposing is actually to reverse the thesis formulated at the beginning of our dispute about ethical questions. You assert: the self is not the basis of ethics, at all; it is, on the contrary, a concept of division, of estrangement between me and another; it is the reason for the impossibility of real goodness.

Varela: Of course the idea of the ego or the self is of pragmatic value as long as it is not understood in an essentialist way; it helps in everyday affairs; it helps to cope with life. But if you understand your own self in an essentialist way as a territorial entity, which is firmly bounded and clearly defined, then you are forced to defend it and to fortify it - and this sense of self or ego then turns into a blockade for a desirable ethics. An identification with an essentialist self is a cause of suffering in Buddhism.

Poerksen: Could one speak about the emergence of ethics, in your sense as well as in a Buddhist sense? All at once, and without central control and determination, a new quality of behaviour emerges, a practice of compassion.

Varela: Exactly. The ethical qualities that emerge then are not the product of rational construction and artificial determination. The point of departure is: responsible action consists in the continual practice of self-exploration. Marvin Minsky’s plea, in contrast, seems absurd: he demands of his readers - knowing full well that he is contradicting his own insights - a lasting faith in an essentialist self and the individual. Can one, I ask myself, justify a moral point of view by means of declarations of faith that one knows to be false? Marvin Minsky’s moral dilemma consists in this bizarre kind of schizophrenia: one ought to behave in a way that contradicts one’s own insights.

Poerksen: Such schizophrenia does not appear bizarre to me, at all. I can give you an example from personal experience that may be helpful in this connection. A few years ago, I published a number of articles dealing with the increasing aggressiveness of German neo-Nazis. In the course of my research, I met a young man who had left the neo-Nazi scene - in the face of grave peril of his life and various bomb threats - and who is now assisting other neo-Nazis in getting out. When I became acquainted with this young man, he still lived in a strongly idealogised world, was still a racist, and was still fascinated by physical violence. And yet, he was horrified by the terrible consequences of his own beliefs, when his so-called “comrades” set fire to a house inhabited by Turkish families so that the inhabitants burned to death. The death of those people really touched him. He did not give up his views immediately but he decided to get out. What I want to say is: his eventual schizophrenia proved to be the foundation of his humanity. The contradiction between his ideological truth and the decision to live and act differently in spite of it, became the basis of an ethics. It transformed a battering Nazi into a compassionate contemporary.

Varela: This example is definitely unsuitable to defend Marvin Minsky’s plea. Minsky demands to believe something of whose falsity one is convinced. The story of that neo-Nazi tells us, however, that a young man realises, for whatever reasons - through intuition, an argument, or some surprising insight - that his ideologically conditioned perception of the situation is evidently wrong and untrue. I suspect that the renewed and less prejudiced analysis was the cause of the change: he parted with his system of beliefs because he had become convinced by arguments, by slowly growing insight, or by his own personal experiences.

Poerksen: But the question here is not at all whether a perception matches the facts or not. The cause for the transformation of that neo-Nazi, in my opinion, was not a new and more correct insight. The relevant distinction is not between true and false but between good and evil. This neo-Nazi changed because he realised that it was bad, that it was unjust, to kill other people, although he continued to consider them inferior.

Varela: I do not see what you mean. When that young man realised that it was not right to kill other people, he rejected and repudiated with this new insight his old belief that it was quite acceptable simply to murder allegedly inferior people. He suddenly realised that the strangers whom he thought to be inferior were human beings, that they suffered, that they were worthy of love and that they deserved his compassion. Such an insight can only come about after a searching analysis and exploration of the situation and the self, which will then gradually change the prevailing belief. You seem to refer the transformation of that young man to some totally independent and moment-bound decision, thereby making this decision appear a wholly rational matter through which one, in full awareness, turns oneself into a schizophrenic. However, this idea of a pervasively rational and totally independent decision is, in my eyes, an illusion: one never decides; one is simply confronted one day by a change in one’s beliefs. At some stage, one contemplates one’s life, comparable to a process of emergence, and finds that an even more fundamental change might be called for.

Poerksen: What do you mean by saying that we do not make any decisions with reference to ethical questions? Perhaps another concrete example, one that seems closer to your views, may be of assistance here. The philosopher Hans Jonas claims, like you do, that ethics is not a matter of rational decision. His key example: you notice a baby lying on the ledge of an open upper-storey window and see it slowly moving back and forth. Jonas says: “Just look - and you know!” The impulse to rush upstairs in order to rescue the little being from falling is so immediate, so spontaneous, and so direct that we simply cannot speak of rational deliberations of any kind.

Varela: The Chinese writer Meng-tzu uses a similar example. It involves a small child on the edge of a well. Who, the taoist Meng-tzu asks, would not rush to the well and pull the child away? But Meng-tzu interprets the situation in a somewhat different way from Hans Jonas: the spontaneous, sudden insight that something which is good for others is also good for oneself, appears to him to be a general human trait. His conclusion is that we do not have to take any decision or invent any rules in such a situation. Spontaneous compassion is, he thinks, already present in all human beings. The virtuous differ from others only because they develop this experience of spontaneous c ompassion further a nd expand it to accommodate other situations; they detach it, as it were, from the very simple and extreme case of the sweet little baby threatened by death. The virtuous have managed to experience, and thus to comprehend in a very profound sense, that we are all one, that humankind possesses a collective consciousness. Such an insight, however, inevitably requires intensive training. We need to train ourselves in a systematic way to be able to assess less extreme and less clear-cut situations in order to react immediately. Buddhism even goes one step further than the Chinese writer Meng-tzu, who believes in the fundamental goodness of all human beings. If the experience of self-lessness deepens, it is claimed, then this may in itself eventually become an expression of the highest ethics, a manifestation of spontaneous, loving care, as it radiates from the Buddhas past and present. They do not radiate this love for others because they have been thinking, nor because they have decided on love, but because their whole being is love. The experience of an absolute reality is love. It is immersed in love.

Poerksen: In your book Ethical Know-How you also refer to this reality immersed in love. You quote the Buddhist assumption “that authentic sorrow inhabits the foundations of all Being and can be made to unfold fully through continual ethical education.”

Varela: I consider this a most interesting hypothesis, not a truth that I would submit to unconditionally. I am not decided as to that, but such an assumption attracts my special attention because I have always had the good fortune in my life to meet people who radiated an unconditional feeling of loving care and spontaneous mercy. It is very moving to see how such love and concern for another manifest themselves in action - without requiring words. Finally, much of what is said in Buddhist circles matches my own modest experiences: the less I cultivate my own small self as the centre, the better I manage to care for others, the better I can listen to my children and pay attention to them and their needs.

Postmodern biology

Poerksen: How, do you think, can we reach a decision on whether there is really something like a fundamentally good existence?

Varela: Well, my answer will probably strike you as quite familiar: “Keep your mind open! Let us continue to look!” The goal is not at all, as Buddhist teachers never tire of pointing out, to accept some dogma without reservation; the goal is, on the contrary, to cast doubts on it and to test it in one’s own experience. We must push on with self-exploration in order to be able to decide about the possible truth of such a hypothesis quite pragmatically.

Poerksen: Studying the teaching parables of the Buddhist masters reveals that their tales and stories keep contradicting conventional morality fundamentally. There is the drunken figure of the holy fool. A crazy sage appears who hacks off one of his disciple’s fingers in order to push him into some spiritual experience. There is the illuminated knave who sleeps with his female pupils. My question is now: how is this absolute ethics and the unconditional, all-embracing, loving care related to conventional morality, which is primarily concerned with leading a respectable life?

Varela: I cannot really say anything precise about that because I simply do not know. However, I want to warn of the premature judgment making conventional moral standards the base for an all-encompassing devaluation and degradation. I am not at all opposed to censuring even extraordinary people but I plead for the proper expansion of the context of observation and for avoiding a fixation on isolated transgressions. Naturally, we may be angry with a master who is always drunk but we must also see his behaviour in the light of his self-effacing activities from which so many people profit simultaneously.

Poerksen: I should like to conclude with a question and a thesis. The question might perhaps - particularly at the end of this conversation - sound strange in your ears because it is directed at something like a relatively stable, attributable identity. Here it is: Who is Francisco Varela? One possible answer comes from the cultural scientist Andreas Weber: he once wrote that you are practising something like a postmodern biology. Among the characteristics of postmodern thinking, whether well-intentioned or not, are the rejection of absolute conceptions of truth and static ideas of identity, the integration of variety irrespective of traditional boundaries, a fundamental enthusiasm for the plurality of the living and for all new possibilities. Would you be content with this categorisation of what you do as a kind of postmodern biology and cognitive science?

Varela: Well, such a label does not make me unhappy nor does it disclose any extraordinary insights for me. I know, of course, that my attempt to combine diverse perspectives and research domains tends to disturb the present scientific scene. And I suppose one could, in fact, describe this integrative posture as a kind of postmodern quality. I cannot, however, identify in principle with the confidence with which the postmodern thinkers believe in the complete baselessness of all things. My love of science and my daily work as a scientist make me assume a more conservative attitude here. I am not sure, either, what label might describe me better. My teacher Chögyam Trungpa once called me an all cheerful bridge and gave me this name. What does it mean? He said that I was a man who always wanted to build bridges, design new connections, and combine different things with enormous enjoyment. That is correct.