6: We can never start from scratch

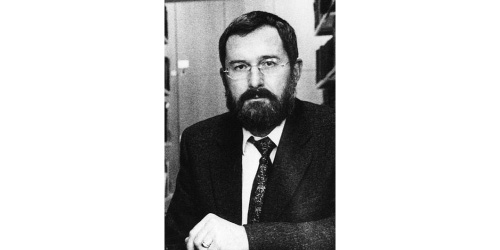

Siegfried J. Schmidt on individuals and society, on the reality of the media, and on the constructivist conception of empirical knowledge

Siegfried J. Schmidt (b. 1940) studied philosophy, German philology, linguistics, history, and art. His doctoral thesis on the relationship between language and thought, published 1968, already rings in one of the central topics of his intellectual life. The question of the different media of knowledge has remained one of Schmidt’s concerns up to the present day. It is the question of what relationship with the world a specific medium demands, enforces, and permits. How can the relationship between language and the perception of the world be ascertained? What principles of inquiry govern science? How does an artist observe? For Schmidt, these are not merely theoretical problems. He began to paint while still a student, he published concrete poetry, and he simultaneously wrote - schooled by an ideal of conceptual rigour - programmatic essays that created a stir in the most diverse disciplines.

In 1971 Schmidt, who had achieved his original academic qualifications in philosophy (doctorate and habilitation), was appointed professor of text theory at the newly founded University of Bielefeld. He soon changed to literary theory, and in 1973 moved to a chair for the “theory of literature”. In the early 1980s, at the latest, he expanded his various interests again, developed - while professor at the University of Siegen - research projects concerning television, and prepared for another change of subject. He is now professor of communication theory and media culture at the University of Münster.

In his books on constructivist themes, Schmidt always pursues a twofold objective: he tests the theory by application and simultaneously works on its elaboration. On the one hand, he uses constructivist assumptions as an instrument to investigate the world of advertising or the irritating power of art. On the other hand, he seeks to develop the constructivist framework as a whole. As the constructivist authors come from very different traditions and disciplines, and either concentrate on the individual or on the culture surrounding individuals as the decisive producers of reality, the points of view are manifold and cannot easily be reconciled. The integrative constructivism advocated by Siegfried J. Schmidt unites the thesis of the cognitive autonomy of the individual with the assumption of the socially fashioned human being: brain and society combine in a new kind of theoretical synthesis.

The starting operations of European philosophy

Poerksen: Doubting external reality is, in the history of philosophy, often enough connected with down-to-earth matters. For centuries, the question has been repeated as to whether the table really exists at which one sits and reflects. Does it continue to exist when I squeeze my eyes shut? Is it still there when I am not present? We are also sitting at a table and discussing the weird-sounding question as to whether there is an absolute reality that is independent from our minds and that we can know. What would you say? Is there a table? Does it exist?

Schmidt: Let me confess: this perpetual question of the existence of a table, laboured since George Berkeley, is illegitimate and implausible. For if I want to know whether this table exists, there already has to be a table in my experiential reality I can deal with. The question of whether this table exists or not is an assertion that neither adds to, nor subtracts from, existence. Where is the table just perceived when I close my eyes? Only a philosopher with an ontic bent can ask such a question; his cleaner could give him the right answer immediately.

Poerksen: Nonetheless, the question does not seem pointless to me because constructivism is repeatedly accused of denying an external reality, of covertly arguing in a realist manner, and of suffering from a disturbed relationship with reality. And such queries are unavoidably triggered by the hard ontology of tables and chairs. The solidity of the wood, the obvious resistance of the real world, which may lead to bruises when bumping into it, somehow seem to contribute to answering the question of existence.

Schmidt: This is indeed a central point because some constructivists like to distinguish between the reality of experience and absolute reality. They claim that absolute reality exists but that they cannot say anything about it, that absolute reality is unknowable. However, such an assumption will, by strict logical consequence, lead to a paradox. People who insist that they can say nothing about reality as such, are already saying a vast amount. How can they know with certainty that it is unknowable and exists independently from our minds? Concerning the problem of the table: when I, a human being, whose only accessible world is the world of my experience, postulate that the table displays absolute reality that I, however, can never know, then I am making a baseless claim.

Poerksen: You, too, once wrote: “The real world is a necessary cognitive idea but not a reality to be experienced.”

Schmidt: In our discourses, we can certainly formulate the assumption that an observer-independent and unknowable reality exists. But such an assertion remains part of our discourse. It is hardly sensible to speculate about what is beyond our discourse because we simply cannot experience it. Why should we distinguish between an inaccessible reality and our experiential world? Of course, we can - speaking with the philosopher Josef Mitterer, whose work I am exploiting here - invent some world beyond discourse that is allegedly inaccessible. All I can say about that world-beyond-discourse, however, must be said in the discourse of my life here and now, where I speak and act. Therefore, such distinctions are practically devoid of meaning; they merge, in the end, with dualist philosophies based on apparently natural divisions between subject and object, language and world, or as just indicated, absolute reality and experiential world.

Poerksen: The fact is, though, that these dualisms have been central and formative for constructivism. Its existence depends on them, to put it bluntly. People constantly distinguish between the real world and its constructed perception, between observer and observed, between subject and object.

Schmidt: These dualisms are the momentous and unrecognised starting operations of European philosophy, which ought to be understood and treated as strictly posited distinctions. Subject and object, observer and observed, were posited as two independent starting units when philosophy was born; subsequently one was forced to relate them in some way, usually favouring one side of the distinction above the other. It was tacitly assumed that such a distinction between subject and object, language and world, mind and being etc. was actually given. Some authors gave priority to the subject, others to the object; correspondingly, subject philosophies and object philosophies were developed and the fact that we produced these distinctions ourselves was conveniently forgotten.

Poerksen: This would mean that the difference between constructivism and its main rival - realism - has merely to do with the direction of thinking. The constructivist says: the observer rules; the observer constructs the objects. The realist claims: the objects affect the observer in a direct way; our images of reality are the consequence and the expression of the observed. Constructivism, if I understand you correctly, merely reverses the direction of thinking, but both realism and constructivism are dualist conceptions and diligently distinguish between subject and object. My question is now: What are you suggesting? Should we give up distinctions entirely?

Cultural programmes

Schmidt: No, that is not the point. It would not be feasible, anyway. According to what we know we can only operate with distinctions, i.e. we are not in a position to do without them. Nevertheless, we may very well ask whether these distinctions and the divisions derived from them are necessary and inevitable. In a consistent non-dualist perspective, we do not presume the existence of any distinction but attempt to derive the dualisms from what we actually observe. The question posed is: what makes us accept this or that distinction as a starting operation? In this way, ontology disappears from our assumptions and presuppositions - and the process becomes decisive.

Poerksen: You separate distinctions and divisions. Why?

Schmidt: I owe this suggestion to Rodrigo Jokisch. He does not put divisions at the beginning because divisions - he argues - always show a preference for one side as opposed to the other. For Jokisch, a division is fundamentally a derived operation; he therefore begins with the level of neutral and general distinctions both sides of which are equivalent, and from there proceeds to divisions, where one side is divided up into a relevant and an irrelevant division. In the philosophy of stories and discourses I am now working on, I make use of this suggestion and set out from neutral distinctions which are transformed into divisions in actual situations, i.e. whenever there is talk and action. Then one side of the distinction is favoured and preferred. This means: on a very general level, we have a neutral system of distinctions, which I call a model of reality. It includes the entire system of distinctions we operate with as observers, distinctions like light and dark, poor and rich, powerful and powerless, young and old, man and woman. They fixate potential positions in the field of societal models of reality. However: it is not yet laid down what they mean; they must be interpreted. The interpretation of the huge network of distinctions is provided by a semantic programme - which I call culture. Culture, in this understanding, is not restricted to art and beautiful things but is meant to interpret the reality model of a society semantically. The knowledge of how to apply this cultural programme according to expectation and how to relate the different distinctions is acquired in the process of socialisation.

Poerksen: Could you elucidate this culture-related model of reality construction by means of an example?

Schmidt: Let us take the distinction between man and woman. Processing the division further on the level of practical action leads to the question: Which is favoured? Man or woman? And when this is decided, then I can observe men or women by means of other divisions - describing them accordingly, for instance, as beautiful or ugly, strong or weak, dependent or independent, reliable or capricious, moral or immoral. They are the specific semantic attributions of these divisions, which are expressed in particular stories and discourses: in fashion and in novels, in pictures and dress codes, in etiquette and legal titles.

Poerksen: In many of your books, you have strongly relied on the work of constructivist biologists, who tend to consider individuals, in an absolutist way, as the more or less autonomous constructors of their own realities. Now you say that culture is decisive, i.e. you assume a certain permeability and receptivity of human individuals to external social influences. How has this change of view come about?

Schmidt: I am certainly not intending to create a new battle front line by now describing culture as the only decisive determinant of knowledge. This would be a misunderstanding and a renewed polarisation that would in no way help us move forward. The capital that can be drawn from cultivating bias has been exhausted down to the dregs. The question of what influences condition the construction of realities simply cannot be answered from the isolated terrains of either biology or the sociology of knowledge. A comprehensive view is required, which relates individual and society in a conception with total processual orientation; I plead therefore, as it were, for an integrative constructivism that unites the three components (brain and body, history and discourse, model of reality and culture). They are all involved in the construction of reality and together form a set of forces that, for analytical reasons, may be divided into a micro-, a meso-, and a macro-level. This division allows for the clear specification of the chosen perspective of observation and the particular research interest when describing models of reality and cultural programmes, stories and discourses, or even body and brain. On the macro-level, the focus is on the dynamic relations between models of reality and cultural programmes. On the meso-level, the macro-level manifests itself in the form of stories and discourses - representing the relations of sense arising from the world of living experience. The micro-level houses the individual actors, who - in the understanding of general systems theory - are considered as dynamic process-systems consisting of bodies and brains. These three sets of forces can only function together: they are all necessary for reality to arise.

Poerksen: From you and other constructivist theorists I have learned that the one and only reality does not exist but only an infinite variety of realities. At every garden fence, so to speak, a new world begins. My question is: can there still be, in this day and age, one and only one culture attributing common meaning to our divisions? Has it not split up into the most diverse perceptual styles?

Schmidt: There is no doubt that it has; and it already started around the end of the 18th century. If the thesis of functional differentiation makes any sense at all, then we must assume that every social system develops its own cultural programme. And that is why - according to my reconstruction - the urgent question arose around the end of the 18th century as to how the cultural programmes of the economy, of education, art etc. that were beginning to drift apart becoming partially antagonistic, could still be connected with each other. The solution of the problem was - to put it quite briefly and with a functionalist bent - to replicate a mechanism available in the economy. There money had been introduced in the course of the 18th century as a semantically empty mode of exchange. Money simply has no semantics, so human performance, talents, and goods could be calculated accordingly for their exchange values. This is the fundamental principle of capitalism: semantics out, numerics in! The cost determines the value. Society, consequently, implemented precisely this mechanism in the domain of culture - namely, the calculation of the value of all societally relevant goods by means of a neutral measuring unit. Culture came to be conceptualised in the semantically neutral terms of law, which were no longer founded on transcendence (by a divine order), on history (by recourse to tradition), and natural law (by invocation of the nature of human beings). Statute law is anchored, as Niklas Luhmann has shown with great precision, in the guarantee of correct judicial procedure. A law may be changed three times in the course of one week, but all that matters for judicial practice is that the law is applied correctly at the moment of judgment. So there is now a semantically neutral rate of exchange that permits the liberalisation of all cultural programmes with regard to their content as long as they do not violate official law - that is the only restriction. You may practise whatever you like in your subcultures but you must neither kill your neighbours nor set fire to their houses.

The limits of tolerance

Poerksen: The law thus appears to be - in this view - the last general foundation of a society that is split up into niches and subcultures.

Schmidt: Exactly. It creates coherence, ties diverging cultural programmes to unfolding individual demands. The law is the last regulative removed from discussion; its execution is not conditioned by another creed, another context of tradition, or another conception of the nature of human beings, but it is, due to its de-semanticisation, equally applicable for everybody. Historically speaking, this is an ingenious achievement - the outcome of social self-organisation, not the work of an individual.

Poerksen: Still, this common foundation of law is obviously not sufficient to guarantee, or at least to promote, mutual understanding. Every subculture lives in its own and perhaps very peculiar world; there is no interaction, no mutual understanding. Only very few people seem to be able to move between these different realities and even to enjoy the permanent confrontation with new and different forms of life and thought.

Schmidt: This does not contradict the development I have just described, not at all. The proper consequence to be derived from what I depicted is precisely that societal cohesion is no longer based on understanding. As long as we observe the law, we may develop our own cultural programmes without understanding each other. The twofold strategy of money and law guarantees that societies do not fall apart even though their individual members are no longer capable of doing things with each other. The rest is private. One seeks out the partners and the parties with whom one believes to share understanding despite all improbability. The result is that the differentiation of society increases constantly and that the extent of indifference keeps growing: a world that appears incomprehensible is, and can be, met with indifference.

Poerksen: You describe in neutral terms a process of relentless individualisation, which cultural critics see as the destruction of public space. Society is said to crumble, and the public domain, in the sense of a common base of reference accessible to all its members, is said to be in jeopardy. What is your view? Do you see this threat?

Schmidt: Firstly: the emphatic notion of a public domain, as for example represented by Jürgen Habermas, has always appeared fictitious to me. There have only ever been partial public domains of differing relevance, which became increasingly differentiated. Additionally, even the so-called mass media only reach specific segments. Nobody should shed crocodile tears over a threat to the one and only public domain. It has never existed as such. Secondly: the fact that societal differentiation is now subject to merely formal control obviously creates specific problems. We have to consider seriously, for instance, how to deal with all sorts of fundamentalism.

Poerksen: The activities of the Scientology sect are, I think, quite a good example of the particular risks run by a society under purely formal control. To put it in your terminology: Scientology exploits the de-semanticised regulative of the law as a defensive argument. The members of the sect demand respect and tolerance - and simultaneously erect a totalitarian subculture.

Schmidt: Scientology is a business enterprise, camouflaged as a moral institution. It insists on ethical neutrality - and massively uses ethics for economic purposes. The problem - also affecting constructivism - is: how are we to cope with the observable abuse of pluralism and tolerance? Constructivist authors have repeatedly been accused of legitimating practically everything, Scientology, and Auschwitz, and the private happiness of the garden bower.

Poerksen: How do you counter the accusation that you promote a dangerous kind of tolerance and libertarianism? Is the constructivist, who wants to remain true to his principles, bound to profess moral relativism?

Schmidt: No, he is no relativist in these matters, and he cannot afford to be. He is also part of a tradition and lives in a particular phase of history, is influenced by stories and discourses. Certain norms, moral standards, and maxims are the result of a complex historical development, which has shaped the constructivist, too. Whenever something happens - people stumble, fall to the ground - we do not begin to worry and to reflect extensively on the right kind of reaction and its justification, but we either help or we do not. It all depends on the moral principles we have acquired.

Poerksen: Where do constructivists find the hold that enables them to distinguish between good and evil?

Schmidt: They find their hold - as all other human beings - in religious or moral beliefs. We have to distinguish here between different levels of observation. At the level of everyday life, constructivists are simply not in any danger of falling prey to relativism; here they decide like all other people on the basis of their unquestioned beliefs. However, constructivists can (on the epistemological level of the second order) reflect why certain norms have succeeded - and not others. That is the proper constructivist perspective: we observe how people observe; observing has become the object of observations.

Poerksen: We do not need absolute values and principles for moral action?

Schmidt: No. All you need in concrete situations is principles that have proved their mettle in your history and in the light of your conscience. We act in continuity of all previous decisions. If you find this kind of moral tie insufficient, you are either an illusionist or a fundamentalist; you run away from responsibility.

Poerksen: If you find, however, that on every occasion you are free to act and decide in different ways, and conclude that your morality is contingent, then you lose something: you deprive yourself of the power that arises from lucidity and unconditional validity.

Schmidt: I cannot agree there. The insight that some behaviour is contingent does not lead to relativism. I can establish, on a level of the second order, that there are alternative ways of deciding moral questions. In concrete situations, however, as an actor in stories and discourses, I act on the level of observation of the first order - and the contingency commandment does not apply. Moreover, contingency at this level cannot be used as an excuse to evade a decision. In this, I am acting as a realist. As soon as you confuse these different levels of observation, however, you are faced with all those chic philosophical problems - and you must torment yourself with questions of whether to practise a philosophy of anything goes, or whether the table ceases to exist when you squeeze your eyes shut and cannot see it any more.

Poerksen: But I would still maintain that constructivism keeps stirring things up precisely because different authors often link those levels in ways that prove to be most enlivening and naturally also provoking. They connect theory and practice, everyday life and epistemology - and then proclaim: there is no ultimate truth, so nothing is secure; we invent reality, so everything is possible; absolute values do not exist, so we must stomach total capriciousness. And so on.

Schmidt: As I see it, this is one of the central weak spots in the constructivist argument. Ludwig Wittgenstein already saw that it simply does not make any sense to expect the world outside to be gone when you walk out the door every morning. As first-order observers - as human beings moving in their environments - we are all ordinary realists; we are not handling constructions but life-world routines supported by good reasons. A position that constantly doubts the reality of our perceptions would be utter counterproductive nonsense at the level of ordinary reality.

Arbitrariness and construction

Poerksen: A quote from Woody Allen: “Cloquet hated reality but admitted that it was still the only place where you could get a real steak.”

Schmidt: Indeed. Steaks are plainly part of reality. And I am indescribably unconcerned by the question of whether steaks are constructed. People who confront first order observers with the thesis that their steaks are not real but only constructs, must seriously face the question of whether they are still quite sane. That is not the level at which constructivism is properly handled because it is strictly a theory of second-order observation, the observation of observers.

Poerksen: How arbitrary and capricious are - in your view - the conceptions of reality that we produce? The concept of construction seems to suggest that individuals can rig up their worldviews in a well thought-out and goal-directed way. In the same way, some constructivists have been speaking of realities being invented by observers.

Schmidt: This is an extremely reckless kind of rhetoric cultivated with glee by some of the old masters of constructivism. Among meticulously and seriously arguing scholars such exaggerated phraseology will produce at best nothing but an incredulous wagging of heads. And the legitimate question is raised: if individuals do and construct everything on their own, why do we need societies and environments? Naturally, even the constructivist has to point out that the environment cannot be simply eliminated; otherwise, in Niklas Luhmann’s nice-sounding German phrase, the jellyfish (German Qualle) will collapse (German platt) for lack of water. And it is obviously most embarrassing and ridiculous when those constructivists who have not really come to terms with their own postulates and assumptions, have to face the legitimate question: How do you actually come by all that knowledge? This is the problem of self-application or self-decapitation: if there were unconditionally valid evidence for their theses, it would have to be precisely the absolute truths the realists have been looking for. So what is the point of claiming with such unconditional emphasis that everything is invented? I have had enough of such extremely irritating guff.

Poerksen: You must explain all the time that one cannot simply construct a beer when dying of thirst in the desert.

Schmidt: Precisely. These are the costs of a popularisation by extreme reduction of complexity, which must now be managed by second-generation constructivists. And when I attend a conference I can guarantee you that someone will come along and say: “Is it really you? Or am I constructing you just now?”

Poerksen: What do you suggest? How should the debate be changed?

Schmidt: I can non longer continue unruffled with the popular rhetoric of excitement and irritation. It has accomplished its function by moving the observer into the centre. Those who are still speaking of an invented reality suggest that it is something arbitrary or intentional. I firmly believe, however, that there are practically no chances of arbitrariness; we can never start from scratch, and we are always too late. Whatever reaches our consciousness presupposes neuronal activities that are independent from consciousness; everything that is said presupposes the command of a language. The construction of realities is dependent on numerous biological, cognitive, social, and cultural conditions, which we are not at all free to control; it happens to us more than that we consciously enact it. We are permanently involved in a breathless process of construction, which is empirically conditioned to a high degree. What is, for example, arbitrary about our conversation? I can only utter what I happen to have in store in my given intellectual situation. You can only understand what your history and biography enables you to understand. Where is there arbitrariness?

Poerksen: I suspect that it is the hope for salvation, the hope to be able to construct the best possible world according to one’s own wishes and without any restriction, which has made constructivism so popular. Now everything depends on what substance is given to the key concept of construction. What would you say?

Schmidt: Sometimes I think that we might perhaps do better to refrain from using the concept of construction, and that we should much rather speak of reality as something emerging, as something gradually forming itself on the basis of stories and traditions. Of course, the concept of emergence is of comparable vagueness but it lacks - and that is essential - both the intentionalist and the voluntarist aspect.

A constructivist media theory

Poerksen: In a meanwhile well-known introduction - to move to another topic - you celebrated constructivism with noticeable euphoria as a “new paradigm” that was going to transform the basic tenets of various disciplines and lead to new ways of observation. You have now been working primarily as a media and communication scientist for a number of years. Could you illustrate your thesis of the innovative effect of constructivist thinking using these disciplines as examples?

Schmidt: The transformation is particularly conspicuous in the investigation of media effects. Here the recipient has been gaining central importance. In a constructivist perspective, recipients play an important role in the processing of the media offerings. For such a user-oriented approach, which has, of course, been discussed f or quite s ome time, constructivism could really prove helpful because it keeps directing us to pose the following question: What are the features of attraction in the materiality of media products that are actually effective in a specific situation and are also actually used?

Poerksen: This radical orientation towards the recipient must entail a corresponding definition of communication.

Schmidt: Certainly. All conceptions of communication as a simple transfer of information must be excluded from this perspective. Communication is understood as a process of the construction of social meaning in the individual. The communicatum becomes an offer inviting operations of exploitation.

Poerksen: What is, for you, the central thesis of a constructivist media theory?

Schmidt: It is of fundamental importance that the relationship between the concepts of media reality and reality should be re-defined. From a constructivist perspective we can say nothing but: the reality constructed by the media is the reality constructed by the media - that is all! The question how this media reality relates to the factual reality or to the one and only reality, is now no more than a topic for journalists dabbling in philosophy, who still believe that it is possible to compare those realities and then excitedly assert: journalism does not represent reality at all!

Poerksen: The kind of media criticism that is based on a realist foundation therefore loses its ontological hold. How does media criticism appear from a constructivist point of view? What is its frame of reference if not the comparison of media reality with the perceptions of reality “as such”?

Schmidt: Constructivist media critics will examine the makeup of a contribution. Their topics would be: selection, staging, forms of presentation. They would - to quote an example - compare the reporting of the beginning of the intifada by the first and the second German television stations. The one German television channel showed police throwing the stones children had thrown at them back at the children. In the newscast of another channel only stone throwing children were shown. The different variants of event selection, staging, and presentation, may thus be compared; one may suspect motives: why do two different stations construct these different realities out of the same event? Why is an event shown in one particular way and not in another?

Poerksen: The well-known journalist Klaus Bresser once said: “The job of the journalist is to convey truth.” This view, epistemologically identical with the position of naive realism, is - according to surveys - shared by the majority of journalists. How is one to comment this kind of professional self-conception?

Schmidt: I think we must distinguish here between this expression of a professional ethos and what can actually be realised in practice. It is perfectly acceptable that the stated professional ethic should exclude purposeful deception, shoddy research, and that it should include the best effort to convey “truth” and to make event and report correspond properly; these are ethical standards and norms deriving from the established practice of journalism, whose utility has been proved in the course of history. Every honest news editor must admit, however, that there are iron-hard rules of selection. And if journalists are aware of that then they can no longer claim with a clear conscience that they are telling people the truth.

Poerksen: There can be no question, however, that such an epistemological position, implying as it does constant doubt, is completely unworkable in ordinary journalistic practice. Journalists need clarity; they need the fiction of ontology.

Schmidt: Much would have been gained if journalists realised, in the first place, that they require this fiction of ontology. They would then have to climb down from the high horse of true world representation.

The production of facts

Poerksen: To corroborate this central tenet that a true representation of the world is impossible, constructivists frequently adduce empirical research results. They have therefore been accused of being naïve slaves to empirical data and of believing with unconditional devotion in the results of brain research, albeit not in the truth. The question is now: what is empirical knowledge for constructivists?

Schmidt: In my book, Die Zähmung des Blicks [The Taming of Vision], I attempt to answer this question and to develop a conception of empirical knowledge from a constructivist point of view. Empirical research, for me, consists in the controlled production of facts; it has nothing to do with reality or truth; it essentially involves the strict observation of specific procedural steps. This means that empirical knowledge can only be knowledge of the world as we experience it and as we then formulate this knowledge accordingly. The facts thus prepared can in no way be interpreted according to an emphatic notion of truth. For this reason, I no longer speak of the collection of data but of the production of facts, and not of data but of facts: these facts are, from the perspective of a sociology of knowledge, something that has been made and produced.

Poerksen: So you only add the constructivist premise of the impossibility of absolute truth to the given armoury of empirical research? That seems somewhat unspectacular.

Schmidt: You may have a point there. There is no total difference between a constructivist and a conventional methodology. The initial assumptions and the evaluation of the results are, however, decidedly different. This approach has irritated some of my critics who have asked me how I could at all employ the procedures of empirical social research on a constructivist basis. My reply: I transfer only the procedures - and not their justification and evaluation. If I want to ride a bicycle, I must do it in the proper way. But this does not justify the conclusion that cycling exhausts the meaning of life for me.

Poerksen: Let me repeat the question: you are continuing to use the classical methods of empirical social science?

Schmidt: Yes. I have developed the concept of an empirical science of literature, which has a strong social science orientation. However, these methods that often originated in a positivist or empiricist context must be integrated into a constructivist framework; and we must be very careful to make quite clear that all observations will only be made with reference to this particular presupposed methodology. All the facts, however carefully produced, are - from a second-order perspective - evidently contingent. That however cannot in any way prevent me from applying methods on the first-order level as meticulously and correctly as is prescribed, and from strictly following the regular steps of the procedures employed.

Poerksen: The approximation of an absolute reality can, if I follow you, no longer be a criterion for the evaluation of research results. What then?

Schmidt: It is the quality of the procedure that supplies the criterion. It is the controllable care in the production and interpretation of facts. Facts are only as good as the methods of their fabrication, and as significant as the procedure of their interpretation. And we must remember that the hardest empirical results turn soft at the moment of interpretation, at the latest: their contingency then appears ineluctable because, for any collection of facts, I can - as is well known from the interpretation of statistical data - generate differing interpretative stories. Nevertheless, there is no alternative to empirical procedure: it tames the roaming vision; it is a sort of dressage; it obviously produces subsequent cognitive costs but also certain profits; and it therefore has its justification. Dressage and discipline guarantee the production of a kind of knowledge that cannot be attained in any other way.

The need for another kind of language

Poerksen: The question is now whether this different and novel understanding of empirical knowledge and science does not require another and a new kind of language. Reading scientific prose, it is easy to see that it is governed by rules of presentation that consistently exclude the observer: one must not say ‘I’, one must not narrate, one must not use poetical metaphors. The linguist Heinz Kretzenbacher once maintained that scientific writing is governed by an I-taboo, a narration-taboo, and a metaphor-taboo. Taking your premises seriously, one should be fundamentally intent on violating these taboos.

Schmidt: Taking the observer seriously obviously excludes submitting to the I-taboo; the metaphor-taboo seems equally nonsensical because metaphors constitute essential elements of scientific speech. Metaphors are bids for orientation and can be exploited for creative purposes, once the idea of objective world description has been discarded. It is of course also possible to understand any interpretation of facts, in a general perspective, as a piece of narration. With full consistency and in strict observance of constructivist principles, every utterance ought really to be introduced with general provisos like “I believe, assume, think, assert...”. Such a mode of writing is, however, most laborious and produces stylistic monsters; that is to say, it has its limits. People who - like some constructivists - clamour for a new language, which demotes the hidden structure of Indo-European languages, are evidently asking for the impossible.

Poerksen: In your professional work, you use a decidedly abstract style but you do not hammer abstraction into a static, final system; you keep breaking the posture of sternness by images, aphorisms, and poems. Nonetheless, I have been asking myself: does not abstraction also make the observer invisible? Abstraction does, after all, detach a thesis from the concrete experience to which it perhaps owes its existence.

Schmidt: Scientific discourse is characterised by a tendency towards abstraction; this is where it differs specifically from other discourses. The question is, therefore, whether to give up science. Do we want to abolish the difference between literature and the science of literature - like many deconstructivists? Do we want to declare - like the misunderstood Paul Feyerabend - that there is really no difference between science and mythology, between academic practice and tribal rites? With regard to these questions I remain, if you like, a traditionalist. As long as the difference between science and non-science offers rewards and makes a difference, I see no reason to reject this opportunity of gaining insight and producing knowledge. Whenever I want to change the levels of observation in order to achieve the respective insights, I must also change the levels of abstraction. Therefore, a second-order observation requires terminological and categorical abstraction.

Poerksen: Alfred Korzybski, the founder of General Semantics, once attempted to develop a new form of language in order to demonstrate to his readers: the word is not the thing; nobody can say everything about an event; everything changes. Out of this very honourable project of a search for a new form grew, we could say with a tinge of malice, a bureaucracy for relativist thinkers. Korzybski proposed to add to every name the calendar year in small print in order to communicate constantly that persons and things change over time (e.g. Korzybski 1933). He further recommended attaching numbers to every ambiguous word in order to express which particular meaning (1, 2, or 3, etc.) was being used at the moment. This proposal is evidently absurd because it implies a kind of exactitude that is unattainable. Are we not obliged, however, to indicate in some way or other that everything can always be viewed another way?

Schmidt: What is definitely necessary is a different kind of level-headedness when positions and conceptions change. One should - and I am not saying this with a high moral tone - firmly insist that one’s modes of expression, one’s needs, beliefs, and experiences may change. I have often been accused of perpetually changing positions, of abandoning them, or of becoming entangled in contradictions. Many consider this irresponsible. I would counter by saying: Whoever keeps saying and writing the same thing should seriously begin to worry. On the contrary, change is an indicator of responsibility; it is not a sign of weakness but may be seen as the living materialisation of the theoretical project thinking in terms of process systems and effect relations. In this way, I can myself experience the thesis that every system is in constant motion and that every reality leads to a reconditioning of systems. Thus the thesis - ironically spoken - turns into a living truth.

Science and art

Poerksen: For many years now, you have been crossing disciplinary borders although this is considered strange in Germany and not much appreciated. You have been appointed to chairs for different subjects several times; you have been professor of text theory and the science of literature, and you are today - having changed subjects again - professor of communication science. Moreover, you have always been active as an artist: you paint, and you publish experimental literature. How do these different forms of life and thought fit together?

Schmidt: They stand in a productive relationship of mutual irritation. It is naturally somewhat stressful from time to time to familiarise oneself with new terminologies, discourses, and expectations, but the life of a crossover professional provides recurring opportunities of viewing apparently familiar things with the eyes of a stranger and functioning as a kind of irritation agent in different disciplines. My art often is really a kind of headwagging about my work as a philosopher or scientist. It has the character of concurrent observation and flows back into my scientific themes in quite different forms; it also allows me to take my scientific work not so infinitely seriously that I would be unable to laugh at it; and it permits of testing alternative paths to knowledge.

Poerksen: You said earlier in our conversation: “there are practically no chances of arbitrariness; we can never start from scratch.” It seems to me that the very purpose of art is to refute such a claim: art is the attempt to realise an act of arbitrariness and freedom - knowing full well that it is essentially impossible.

Schmidt: This is also a central motive behind my own creative work, I would indeed say. One attempts the impossible with some chutzpah even though one knows it to be impossible. Nevertheless, this has a special charm of its own. Here is a modest example: a few years ago I published a small book entitled: Alles was sie schon immer über Poesie wissen wollten [Everything you wanted to know about poetry]. In 31 chapters, I pretend to give the ultimate information about what poetry really is. Today, I no longer know myself whether the texts in this book are quotations, paraphrases, commentaries, or pure inventions. I am fascinated by this kind of hybrid text because it entangles in the form of a cool game what I am trying to disentangle day and night in my existence as a scientist. At some point whatever seems self-evident and whatever is believed to be valid is set in motion. Moreover, questions emerge: Does poetry really exist? Does language? Is there silence? Does this author have a style? Does he still exist?