7: The freedom to venture into the unknown

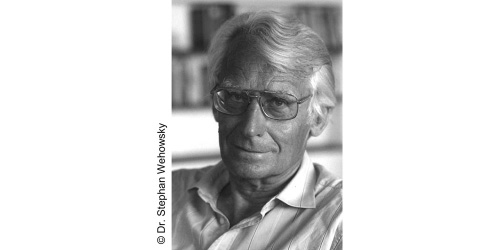

Helm Stierlin on guilt and responsibility in systemic and constructivist thought, on the dialectical nature of human relations, and on the ethos of the therapist

Helm Stierlin (b . 1926) studied philosophy and medicine, obtained doctorates in both subjects, and went to the USA in 1955. There he first worked as a psychoanalyst in the Mecca of analytically oriented psychosis therapy, the hospital of Chestnut Lodge near Washington, 1956-1961. He soon felt himself in disagreement with fundamental doctrines of psychoanalysis. He came to consider the fixation on the individual patient and the exclusion of family members, as decreed by Sigmund Freud himself, was mistaken because, in his medical practice, he was constantly confronted with the power of family ties.

In the 1960s, Stierlin became attracted to the early developments within the slowly growing movement towards family therapy. He designed projects of his own, conceiving of a family as a network of relations involving loyalties and delegations, and began to comprehend families as systems governed by their own specific rules of reality construction. Inspired by Hegel’s central figure of thought - dialectics - Stierlin developed a particular sensitivity for the dialectics of relations, the perpetual interplay without clear beginnings, the entanglement of oppression and obedience, power and helplessness. The title of one of his books, Das Tun des Einen ist das Tun des Anderen [The Doing of the One is the Doing of the Other], expresses, for him, both a research question and a programme: what people do seems to him comprehensible essentially through their fields of relations; it remains incomprehensible without taking the other into account: it would not even exist without the other.

Being trained in this kind of dialectical observation, one can recognise how the desire for closeness and the sometimes escape-like search for distance determine each other, how the power of one individual preserves the weakness of another, and how - conversely - the weakness of one person enforces the power of another.

Dialectical and systemic thinking finally brought Helm Stierlin back from the USA to the scene of European therapy. In 1974 he was appointed medical director of the Abteilung für Psychoanalytische Grandlagenforschung und Familientherapie at the University of Heidelberg. Since the early 1980s, Helm Stierlin has been working on integrating the systemic view, which deals with the ties of individuals, with constructivism, which postulates the autonomy of individuals. His principal interest is not the highlighting of opposites but the integration of diversity; it is synthesis, the goal of any dialectical effort.

The view of the systemicist

Poerksen: Our everyday notions of a reliable and calculable world include the assumption that reality is governed by recognisable and decipherable laws, that a cause leads to an effect in a linear way, and that we can refer any effect to its specific cause. The central assumptions of systemic-constructivist theory and therapy that you represent are, however, that there is little sense in thinking in a linear-causal way because everything is circularly connected; whatever happens manifests itself in utterly entangled chains of effect.

Stierlin: Well, I would not formulate my views in such an extreme and global manner. When a surgeon treats and cures a leg, then a certain linearity of thinking and acting is definitely required. The same applies to a rupture in the tyre of my bicycle and many other occurrences of ordinary life; we know very well there what has to be done step by step. With regard to the domain of relations, however, linear-causal thinking becomes questionable. There we realise very quickly, how profoundly cybernetics and other systems sciences have been revolutionising our understanding of living systems, and we begin to pay attention to feedback effects and processes of self-organisation. We can see what enormous effects a single impulse in the domain of relations may release: they spread within an internal field of forces, propagate itself, and generate an enormous spectrum of possible reactions.

Poerksen: One of the implications is that the consequences of one’s actions become largely unpredictable: we must always reckon with surprises. What are the advantages of such an essentially uncomfortable view for the therapist?

Stierlin: A consequence and an advantage of this point of view is the new modesty required on the part of therapists. They can never know precisely what their interventions will release in other persons because those persons will process any intervention within their own systems according to their expectations. Doctors naturally use their experiences, which may help them to envisage eventual results. All the same, we can never be certain. The circular-causal view relativises the presumption of therapeutic and curative omnipotence; and we begin to acknowledge the autonomy of the patients.

Poerksen: But even as a therapist, I must keep thinking in a linear-causal way. My thesis is: you need a trivial conception of causality, raw mechanistic thinking, in fact, otherwise your actions become meaningless and completely unpredictable activities.

Stierlin: Such a conception of causality is less involved in curative and therapeutic activities than in the exercise of power and control. The questions here are: Who is going to win? Who has power? Who will prevail and with what means? The point is to impose behaviour on other persons that they must follow - unless they decide to rebel. Therapy and control are, in my view, not very closely related although both forms of intervention tend to mingle in psychiatry due to linguistic standardisation: a psychiatric hospital is by definition not only intended to cure patients, it also provides controlled protection against people whom society has defined as potentially dangerous.

Poerksen: Whenever you enjoy a feeling of pride after successful therapy, do you not refer your success to the linear efficiency of your interventions?

Stierlin: Pride is not the right kind of expression; it goes against my systemic understanding, which makes me aware of the limits of my influence. It is rather a feeling of satisfaction that one has not committed too big mistakes and that one’s intervention was useful. I am indeed surprised sometimes what clients can achieve in a short time.

Poerksen: In your own practice, you often work with complete families; you do not only treat ailing individuals, but you ask parents and children and perhaps grandparents or peers to attend a meeting. Could you give an example from your therapeutic practice that might illuminate the particular character of systemic procedure?

The dynamics of self-destruction

Stierlin: Let us look at the case of an anorexic girl. It is one of the dilemmas of anorexia that the required detachment is fraught with difficulty because such families are often dominated by strong fears of separation and rigid either/or thinking. This is to say: either I am part of the family system, loved, and appreciated - or I am actually outside. With a girl that turns anorexic eventually, the individuation is often retarded; she is loving and well adjusted. In a society obsessed by dieting, and idolising skinniness, she may moreover be taunted, begins to reduce weight and develops a fanaticism of control leading to anorexia and an ultimately destructive triumph of will. Anorexic girls struggle to detach themselves, reject all food, and gravely hurt their parents, who are increasingly upset by the child starving herself to death. Anorexic persons become aware of these reactions, of course, suffer from a bad conscience but despite all carry on thinning. The entangling attachment grows even stronger.

Poerksen: Just to make the contrast to other variants of therapy quite clear: psychoanalysts probably would, when confronted with an anorexic girl, start with the game “Let´s blame the mother!” They claim that it is, in most cases, an unsatisfactory early relationship between mother and child, which causes anorexia, in the end.

Stierlin: Quite so. Psychoanalytical patterns of explanation always presume an assortment of conflicts and traumas originating at a very early developmental stage, consisting, for instance, of a rejection of femaleness and a strong attachment to the mother. Early childhood traumatisation, therefore, requires, in the view of analysts, the extensive actualisation of the conflicts through a process of transference and counter-transference.

Poerksen: What, by contrast, does the approach of the systemic therapist reveal?

Stierlin: It uncovers the entanglement; it reveals the effects the anorexic girl has on the family and vice versa. The anorexic person has two concerns: she wants to disengage herself from the parents and control her own body. These needs are satisfied in the course of the illness in such a way as to produce further effects within the system of the family. The anxiety and the angst of the parents give the sick girl an enormous power that may, in addition, release feelings of guilt; and the active control of the individual body leads eventually to an increased dependence on the medical establishment, which intervenes at some stage, treats the starvation damage, may even order force-feeding, and thus introduces total control. The girls in question often react with counter-control, hoodwink the doctors, and just drink a few litres of juice shortly before weighing. In brief: what we recognise are circular patterns of interaction, enmeshed vicious circles, which may, in the extreme case, lead to the girl’s death. Anorexia, in this kind of family, appears to be the ingenious solution of an insoluble situation. The anorexic individuals radically disconnect themselves; simultaneously, however, all family members remain entangled with each other in close emotional relationships.

Poerksen: Viktor von Weizsäcker often retorted brusquely, when asked about mental and bodily illnesses: “Yes, but not in this way!” With regard to anorexia, this means: the detachment is imminent but both the form and the strategy chosen are wrong. They create a new form of dependence and intensify the relations, which should have been severed in a positive way.

Stierlin: You may see it this way, but I do not like this interpretation. It reflects the perilous either/or thinking that we must definitely overcome. The issue is neither complete disconnection nor total attachment. Both states are unendurable. The goal is to develop, by trial and error, a healthy intermediate form, which I have called related individuation: the ability to disengage oneself, to pursue one’s ideas and ideals, and nonetheless to remain related to the parents and the family, and to keep re-adjusting this relationship on new levels all the time.

Poerksen: So how do you manage to change rigid thinking in oppositions and - if you like - the patterns and playing rules of the interacting systems?

Stierlin: Put quite generally: the willingness of the girl to change is decisive. The decision to starve must be corrected by the message that this kind of starvation is not good for the body. How to formulate this message in such a way as to make it work cannot be stated in general terms. It depends on the individual case. Some girls are very amenable to the paradoxical character and the absurdity of the situation - and can make this kind of thinking their own. Others display stubbornness and play with the anxiety of the parents. Still others can be caught with humour. From the therapist’s point of view, it is essential to start out from the girl’s notions of autonomy and to aim at her level of comprehension.

The question of guilt in circular conditions

Poerksen: If we transfer circular thinking to the questions of guilt and innocence, then we will inevitably start to feel slightly uncomfortable. We are forced to state: all participants are guilty somehow; each one is responsible - because all the effects are reciprocal. And if we want to be consistent, we will necessarily end up with the idea that, in reality, nobody is responsible any more. The question of guilt vanishes in the vicious circle of interactions. “Systemic thinking thus leaves behind” - a well-known therapist formulates quite consistently - “the categories of cause and effect (and, therefore, of guilt) in favour of a circular view.” Would you agree?

Stierlin: Not at all. Hearing something like that immediately stirs up my opposition and a strong antagonism towards such a naive and dangerous global claim of circular understanding, which is alleged to ring in the last hours of the responsible individual. The systemic and circular view is also, quite clearly, nothing but a model that has its limits. It is only one part of the approach; the constructivist perspective, which emphasises personal initiative, personal responsibility, and therefore personal guilt, must supplement it. The more we recognise ourselves as the constructors of our relational realities, the better we comprehend ourselves as responsible for the realities we have constructed. We should ask ourselves, particularly when confronted by an image of circular entanglement: what is it that makes a difference? We are, after all, observing a game that is being played. The answer is: it makes a difference that one of the participants drops out of the game, stops observing the rules, will not rise to provocation any more, and thus violates the laws of a well worn manner of conflict management. Perhaps the entire quarrelling game is destroyed in this way. Naturally, there is no telling how such a step will affect the system of relations. But without this risk of essentially unpredictable reactions, without personal initiative and without personal responsibility there can be no progress, none at all.

Poerksen: My claim is, however, that systemic thinking forces you to abandon the idea of the autonomous individual and, consequently, the idea of personal responsibility. The individual appears in the relevant literature - I quote again - as a mere “element in a control circuit.”

Stierlin: I am aware of these pronouncements, but the position I take here is decidedly different; it connects autonomy and dependence, not forcing them into an opposition but relating them dialectically. I think that you cannot be solely autonomous or dependent, solely victim or perpetrator, solely powerless or in total possession of power. Autonomy is possible only when human beings are able to reflect, at the same time, their dependence on other people, healthy food, fresh air, and a state under the rule of law that guarantees and safeguards a life of freedom within limits, in the first place. Autonomous action includes, consequently, the acknowledgment and acceptance of vital dependences. Perhaps this sounds a bit difficult. However, my claim is that autonomy becomes possible precisely when people gain an awareness of their dependence upon others and begin to reflect the consequences of their loyalty to a group or to an ideology. Moreover, we naturally come to appreciate our dependence whenever we struggle to assert our autonomy and try to question the conditions of our affiliations and our principal distinctions.

Poerksen: Those who become aware of their suppression gain freedom?

Stierlin: I believe so. It is a reflective distance that enables us to observe the causes of suppression as though from outside. And this distance renders the possibilities of freedom even more real for us; the options increase; we assume responsibility for our decisions, for exploiting or disregarding opportunities. We begin to see the reasons for our obduracy, we recognise the double binds and the impasses - and discover new domains of play and the practically infinite possibilities of interpreting the processes of events, of establishing causal chains, of creating sense, and of designing and redesigning the multiverse existing inside and between human beings.

Poerksen: You are trying to reconcile, if I understand correctly, the idea of the autonomous individual with the notion of the human being that is shaped by particular circumstances and remains entangled in them.

Stierlin: I think that we need to see both together in order to recognise how autonomy and dependence determine each other. My own responsibility and my autonomy will become clear to me only if I become aware of how dependent I am upon others. Perhaps the image of the flying bird is helpful here, the primal image of the wonderful feeling of freedom, illustrating the concurrence of opposites. Its freedom in flight is both expression and consequence of its being borne by the air.

Poerksen: It might be objected here that the understanding of the conditions of one’s dependence can, conversely, be exploited for the purpose of denying and renouncing individual freedom and personal responsibility. Rudolf Höss, the commandant of Auschwitz, for instance, asserts in his biographical notes: “I had unconsciously become a wheel in the big machine of destruction of the `Third Reich´. The machine has been demolished, the motor has gone under, and I must with it.” Rudolf Höss is thinking systemically here, to put it maliciously, to be able to present himself as a victim after the War.

Stierlin: This is a very good example to show a way of arguing that is widespread not only among Nazis. There are exactly these two contrary possibilities of using systemic thinking. One can - and it does indeed frequently happen - use a systemic view as a legitimating argument in order to fend off one’s responsibility and personal guilt: one declares oneself a small wheel in a big machine that cannot be controlled. However, the reflection of one’s dependence is also - in my view - a way of making oneself better aware of the options that are always available and of one’s own autonomy so as to take on responsibility for one’s actions within the limits of a finite life.

The paradox of freedom

Poerksen: I sympathise with such a view but I just cannot help finding it contradictory. If I claim that a human being is enmeshed in a certain system of relations, then I am thinking deterministically and negating the possibility of personal autonomy. If I claim, however, that individuals are free and responsible, then I must, at the same time, be negating all possibilities of external determination. Otherwise, there is a logical contradiction.

Stierlin: Systemic and constructivist thinking implies bidding farewell to the grand designs, the ideologies, and the apparently final solutions, and to face up to the risks and uncertainties of life in full personal responsibility. In this process we must also, at some stage, accept the limits of western binary logic and familiarise ourselves, as individuals acting in self-awareness, with the perpetual paradoxes of our existence where human reason founders. Total logical consistency is simply not to be had in the process of life. Lenin already abused logic as “the greatest whore”: it is available for everything.

Poerksen: Perhaps anti-logic is a whore, too, and freely available.

Stierlin: Logic and anti-logic are two extreme forms of viewing reality. We must act as mediators between them and other views that are not rational. My medical colleague Ronald Grossarth-Maticek once asked 5000 academics to name their criteria of sense, validity, and truth. Scientists and scientifically minded psychologists declared that, for them, only the logical, the idiot-proof rational, had any validity. A small group of only about 15 percent said that, for them, sense and truth lay only in what they found intuitively and emotionally evident. Their motto was: I trust nothing but my affect logic! A further group, also rather small, took a middle stance between these two extremes and attempted to connect a logically founded view with an intuitive and emotion-guided construction of reality. This is difficult and complicated because such attempts unavoidably meet with paradoxes, contradictions, and inconsistencies. As for myself, I would certainly like to join the group that unites logic and emotion. I am troubled by Hannah Arendt’s question how it was possible that so many Germans succumbed to the allure of power during the period of National Socialism, and why there were so relatively few that responded with purely human feeling. Where was the spontaneous reaction of compassion for the persecuted? The majority yielded to the omnipotence of a pseudo-rationality deriving from the ideological system. In this ideological system Jewish fellow citizens were a disease that had to be eliminated - without soppy sentimentality and with the professionalism of a surgeon. Here, too, rationality had become a whore due to the lack of the counterbalancing feeling of compassion.

Poerksen: Reviewing our conversation so far, I am struck by a way of thinking that is constantly struggling for a dialectical balance: you link the needs of individuals and families, systems theory and constructivism, autonomy and dependence, freedom and suppression, reason and emotion. One senses - as one of your sources of inspiration, the philosopher Hegel, would put it - a desire for synthesis, for the elimination of opposition and diversity in a new, superordinate unit.

Stierlin: Your observation is quite correct. The concept of dialectics is, for me, a sort of magical word that has fascinated and inspired me since the days of my university studies. And you are quite right: the goal of my thinking and my therapeutic work is not the immovable front, the indissoluble and unbridgeable opposition, but a kind of inspection that focusses on the individual case and primarily aims at reconciliation. This does not at all imply, however, that differences are to be blurred and contradictions argued out of sight, that everything is to be plastered up by a grand synthesis, that tensions are to be removed, and that a totalising notion of dialectics is to be employed to bring about final harmony. What is, in fact, meant is the intention to work on the concrete case and to seek to discover new answers every time, to explore the relational dialectics of a togetherness that is as alive as possible, and where new contrasts and new balances keep arising all the time. Once more: to achieve an adequate intervention as a therapist, one does not need the grand concepts or the universal directive for any imaginable occasion; what you need is the sensitivity for the individual case. Then you must act quite pragmatically.

Poerksen: You change your way of thinking according to the situation?

Stierlin: Definitely. Linear and circular causality, the models of cause and effect, the notions of individual and system, autonomy and dependence etc. are all lenses of cognition, which I apply or exchange according to the given situation. The reason for the necessity of such pragmatic choice is that these lenses open up a particular view of the world and exclude another. One must weigh up which perspective is most useful in the given situation.

Poerksen: Karl Popper and the disciples of his philosophy of science maintain that such a procedure does not satisfy the requirements of science. Karl Popper insists on the explicit statement of the conditions that might refute and falsify one’s assumptions. Now you are working with theses and theories that fundamentally contradict each other; you assert the autonomy of individuals and, at the same time, their captivity in systems. The consequence is that proceeding in this way prevents failure through a clash with facts because any kind of behaviour can be integrated as possible evidence.

Stierlin: My reply to the Popperians would be: let us take a specific case - e.g. a psychosis - and apply our different cognitive lenses! What will we gain - my question would be - by observing the illness through the lens that reveals the internal conflict dynamics of the patient? What do we see when using the family lens and the systemic lens? The fact that such an approach is not based on eternally valid principles and theories seems to be a moral problem for certain people; they accuse one of capriciousness. My view is the exact reverse. The lack of complete recipes is, for me, both expression and consequence of moral sensitivity: one allows oneself to be guided by the requirements relevant to the given situation and by one’s own experience. In dealing with the concrete case, the arbitrariness of a pragmatic approach with multiple lens adjustments, which is deplored by some, quickly evaporates.

Poerksen: Is there really no superordinate point of view when you are choosing your lenses according to given needs and momentary efficiency?

Stierlin: It derives from the general perspective of systems theory and the medical situation: one is always confronted with a problem that is experienced as painful. Therefore, the central questions and maxims are: what can be done to reduce pain? Might the restored well-being of the individuals and their successful self-regulation bring new pain to the other suffering members of the family? Does the avoidance of pain suffocate creative tendencies? The goal should always be to reflect the consequences for as many most widely differing systems domains as possible in order to uncover a maximum of subsequent effects.

Poerksen: Are such mobility and this sensitivity to effects learnable, or is one not bound to fail as a result of the complexity of the circumstances and the necessarily restricted capacity of comprehension? Even the grand old lady of family therapy, Maria Selvini Palazzoli, once admitted that systemic thinking is feasible only for moments at a time.

Stierlin: Systemic thinking can only be learned through one’s work; it cannot be instilled into others; it needs time to gather experience and to make mistakes. Naturally, such a way of thinking is not without its risks because it introduces new complexity that in turn requires complexity reduction, which may then become the source of new hang-ups, new claims to salvation, and new ideologies.

The fundamental systemic maxim

Poerksen: Is systemic thinking not, in fact, bound to remain the business of an élite, which interferes with people’s completely legitimate desire for simple orientation? Systems theory is, after all, only of interest to a relatively small circle of initiates equipped with a certain intellectual hunger for mobility.

Stierlin: What is the alternative? Should we abandon theories and the knowledge we might derive from them simply because they frustrate the craving for complexity reduction? Are possible difficulties of comprehension really valid arguments against the theories themselves?

Poerksen: My point is this: the systemic models of thinking, which expressly claim to offer universal orientation, require years of intellectual training and in due course undermine securities and destroy aspirations towards truth. Perhaps only a small number of people can stomach these consequences.

Stierlin: I cannot agree. A systemic attitude to oneself and others and the practice of self-regulation in daily life, which lead to greater well-being, are not a question of intelligence. They do not have to be connected with the understanding of a complex intellectual system. In my practice of family therapy, I am constantly surprised by how rapidly even relatively unsophisticated persons are won over to the systemic view and put it into operation for themselves with the effect of positive change. Difficulties arise, by contrast, with the intellectually refined, therapy experienced, and academically educated, Heidelberg population.

Poerksen: Is it really the other way round? Is it intuition and not so much the intellect that is needed for systemic understanding?

Stierlin: What one needs, what one should take to heart, apply, and defend against others, is above all a fundamental systemic maxim that sounds terribly simplistic: one should do more of what is good for one in the long run. There are so incredibly many people who cling to internalised fundamental beliefs and directive distinctions that force them to act right against their own well-being. They give up sexuality, they deform and twist themselves in order to win someone’s love, and they struggle interminably to satisfy foreign demands.

Poerksen: Do you think that your special situation of inquiry, as practising therapist and theorist, combining theory and practice, intuition and abstraction, is particularly productive intellectually?

Stierlin: It definitely has enormous advantages because it keeps me away from the interminable and sometimes totally superfluous conceptual pettifogging of some of the systems theorists, sociologists, and psychologists. In my situation as doctor, I am permanently compelled to test the practical value of a theory. I am infinitely grateful for this constant test through daily practice; it prevents the detached and alienated playing around with ideas that I found so terribly painful as a beginner student of philosophy. When I eventually started studying medicine, it felt like some sort of deliverance; the concrete questions, the critical examination of disease and pain, and the work on corpses made me find my feet again.

Poerksen: What do you as a practising therapist and theorist understand by a system? Is it a free creation of the human mind? Or do systems exist?

Stierlin: A system is a totality, which possesses a quality that is more than the sum total of its elements. What observers accept as a system, depends on them and on the answer to the question of where the boundary between system and environment is drawn. Is a bacterium, a rat, a human being, or a family a system? Systems are, in my view, more or less meaningful observer constructs. This becomes quite clear when we consider the concept of a problemsystem: the therapist as observer reflects which elements make up the pain-causing system and which do not. The married partners? Must the whole family be present? Is it necessary to observe several generations?

Poerksen: Quite generally: what therapeutic methods result from systemic and constructivist insights?

Stierlin: Techniques and methods will be allotted a place in systemic-constructivist therapy if they are helpful in effectively creating differences that make a difference. They must be adjusted to the level of expectations and perceptions of the clients, and they should be judged as health improving by all the members involved in the system in question. Naturally, classical psychoanalysis also introduces differences but it remains fixated upon the narrow context of a dyadic relation; the cognitive lens is restricted to internal mental conflicts. Systemic therapists, however, embed the conflict in the relevant relational system. Their horizon for therapy and diagnosis is wider.

Poerksen: How does one proceed as a therapist in practice? Could you give a few examples?

Stierlin: One of my guiding lines is that it is impossible to formulate ways of proceeding that are independent from situations and contexts; I therefore find it difficult to give an answer. Quite generally, however: one of the most important instruments is quite definitely the technique of circular questioning. One asks, for instance, a family member in an undirected way that equally permits the search for distance or closeness, about the conflicts, expectations, and needs of another member. All the persons present are thus given a practical demonstration of the relativity and mutual conditioning of their perceptions. The goal is to stimulate mental search processes and keep something in motion, to open up new perspectives, and to increase the autonomy of every individual. Concisely: the analyst interprets, the systemicist questions.

Hard and soft realities

Poerksen: What role does language play in this process? Is it an instrument of seduction, of communication, a vehicle of reciprocal understanding?

Stierlin: All that. Whenever we seek a hold and an orientation and even a safe footing in a bottomless void, we are dependent upon language; language is, to quote Martin Heidegger, the house of being that guarantees stability. It is used to harden distinctions, it marks a supposedly static reality that is beyond doubt; it declares something proven and unshakable and serves in formulating non-negotiable positions; but it also permits us to liquefy fundamentalist claims to truth and rigidified reality constructions for therapeutic purposes. We can point to the consequences of such certainties, question them directly or indirectly, bring the counter concept into play, in order to show and present the relativisation of the original concept.

Poerksen: It might appear now that systemic therapists in their basic enthusiasm for new possibilities are primarily responsible for the liquefaction of reality constructions. Is that correct?

Stierlin: No. If irreconcilably phrased views clash, then the goal must indeed be to soften them. Questions and provocations, humour and impertinence then serve to create a new dynamics. Such an approach is often apposite when the suffering in question has psychosomatic causes. However, one can also imagine schizophrenic scenarios, where everything seems vague and fluid, unstable and undifferentiated. Here a hardening may be called for that would open up a first possibility of seeing a difference that makes a difference.

Poerksen: How do you actually do that? How does one harden a reality by means of language without marking off boundaries in a direct and linear-causal way?

Stierlin: One of the key problems of schizophrenic communication are notions of conflict that are characterised by an implacable, rigid either-or logic: there is either total detachment and complete separation, or absolute union. Given conflicts are not addressed because that would be too much of a threat. Schizophrenics tend to develop a sort of communication that keeps everything vague, shuns all determination, and mystifies everything. In such a situation, the prime target is to reach the conflict, to have it articulated. If one attempted to do this in too direct a way, one would frighten these persons and heighten their fears. Therefore, an indirect way is chosen, which might, for example, counter the schizophrenic and all-diffusing babble by an even more confused communication from the side of the therapist. Somewhere in the process a moment arrives when the client says: “Doctor, stop it now! Let us have some clarity at last! And let us get down to brass tacks, at last!”

Poerksen: Preparing this conversation, I came across these and other tricks in books by various authors, and from time to time the question arose as to whether these authors were actually good people. I was struck by a style oscillating between coldness and excitement, by a strange distance between the therapists and the people whose difficulties they analysed. What might be the reason, do you think, for being moved to asking this question of goodness when reading systemic literature?

Stierlin: I simply cannot tell you; it is your question. It is certainly possible that a kind of prose that struggles intensively for scientific legitimation and barely touches the heart will occasionally strike one as repulsive. But the other extreme would be a kind of emotional playacting as used to be extremely popular once in the scene of American family therapy; the style of some authors is also a reaction against such an exaggerated emphasis on feelings. When I study this kind of literature, I am interested to see whether the presentation is successful, whether the author has managed to translate abstract ideas into vivid descriptions and make them fluid again. And what are good persons supposed to be like, anyway? How does one identify goodness? What are the recognisable signs of goodness?

Poerksen: One feature might be that good people love human beings.

Stierlin: But what is love? These questions of goodness and love seem to me to be attempts at reducing complexity: they simplify, they supply neat formulas for extremely complex affairs.

Poerksen: The question arises then why you find complex thinking more attractive and desirable in any event. Is there a systemic key experience that you might perhaps like to describe?

Stierlin: Yes, this key experience occurred as far back as 1957. I had just started work as an analytically oriented psychiatrist in the American clinic Chestnut Lodge. My first patient in this clinic was a girl student who was admitted in a catatonic state. She did not speak and was completely rigid. The rigidity began slowly to recede, however, a good contact developed, and she openly talked about her conflicts. Then something very strange happened: suddenly her father appeared, took the patient away, literally overnight, and left me there in quite a daze; it had, after all, been my first case in the clinic of Chestnut Lodge. My supervisor, at the time, consoled me with the words that the first sign of recovery often was precisely that the parents came to take their child home from the hospital. I formed the impression then that the loyalties that keep persons tied into the system of a family are much stronger than the forces manifesting themselves in the dyadic relation of a therapy.

Poerksen: You had discovered the power of the unconscious in the domain of relations.

Stierlin: Exactly. It was this power of family loyalties and bonds, which was obviously active in relations, that occupied my mind after that experience and that I intended to use in therapy. That experience in Chestnut Lodge never left me and finally led me to family therapy. Some time later, I described the forces involved as transgenerational loyalties and delegations. Observing these forces from outside makes one realise that they are powerful enough to keep a patient in a state of schizophrenia.

The era of the textbooks

Poerksen: Today systemic and constructivist thinking, which was then in its beginning stages, has become increasingly popular. My question is now: might it not be dangerous both for systems theory and constructivism to gain in dominance in public and academic discourse? For me, systemic and constructivist thinking is really meaningful only as a sort of antagonistic epistemology that functions as an antidote against the arrogance of dogmatically hardened claims to objectivity. The moment it becomes dominant it loses its function. Such a way of thinking should always - put somewhat pompously - remain a philosophy of the underdog.

Stierlin: That will hardly be possible, but I personally do indeed regret very much that the era of the textbooks, the times of popularisation and politicisation have set in. This means that a phase of creative anarchy is inevitably ending. And one now risks becoming the victim of one’s own success. The history of psychoanalysis is a cautionary tale. There is an enormous difference between the revolutionary types of the founding generation, who stood up - most of them outside the universities - against the psychiatric establishment, and the meanwhile established analytical mainstream philosophy, which now dominates the universities. I certainly do not wish this to be the fate of constructivists and systemicists. I am not unduly worried, however, as a committee of experts, consisting mainly of authors of an analytical persuasion, has just scientifically certified once again that the systemic approach is unscientific. Therapists working in this way are, therefore, excluded from the remuneration by the general health insurance companies. This is not merely a bad thing; it leaves one free to think in a non-conformist way, to venture into new things and try them out.

Poerksen: To conclude: do you think that systemic thinking might also be useful outside the therapy room? It is after all pleading more or less clearly for new ways of meeting and treating our fellow human beings and our whole environment.

Stierlin: To put it as a matter of principle: the new understanding of complex relations is accompanied, in my view, by a new kind of humility and reverence, which is changing our relationship with the world and all other human beings, and which is therefore undoubtedly helpful. I always like presenting the example of a single human finger. In this one finger alone there are 1,5 thousand million cells. Each cell contains all the genetic information, i.e. about 100,000 genes. In addition, each cell is a sort of power plant in which 2000 chemical processes take place simultaneously. In this finger alone, there is unfathomable complexity: it necessarily makes us marvel, and it cannot but inspire humility before the enormous power of the self-regulation of life. Such marvelling humility is, of course, not meant to manifest itself in a passive attitude of adoration and veneration that might eventually even lead to a sort of systemic fatalism. I am much rather concerned with a kind of awareness of complexity that meets the challenge of a reduction of complexity that preserves complexity. We must, therefore, tackle the question of what is essential with a maximum of systemic imagination and perceptual power. On the other hand, we should - in the awareness of our own limitations and with the never-flagging reverence before the enigmatic aspects of our existence - act in a responsible and decisive manner.