Maria Stewart  New England Anti-Slavery Society, Boston, September 21, 1832

New England Anti-Slavery Society, Boston, September 21, 1832

Maria Stewart, who had gained public recognition as a contributor to the antislavery newspaper the Liberator, was the first woman of any race to deliver an address to a mixed-gender audience on political issues.

Excerpt:

Few white persons of either sex, who are calculated for any thing else, are willing to spend their lives and bury their talents in performing mean, servile labor. And such is the horrible idea that I entertain respecting a life of servitude, that if I conceived of there being no possibility of my rising above the condition of a servant, I would gladly hail death as a welcome messenger. O, horrible idea, indeed! to possess noble souls aspiring after high and honorable acquirements, yet confined by the chains of ignorance and poverty to lives of continual drudgery and toil. Neither do I know of any who have enriched themselves by spending their lives as house-domestics, washing windows, shaking carpets, brushing boots, or tending upon gentlemen’s tables. I can but die for expressing my sentiments; and I am as willing to die by the sword as the pestilence; for I am a true born American; your blood flows in my veins, and your spirit fires my breast.

I observed a piece in the Liberator a few months since, stating that the colonizationists had published a work respecting us, asserting that we were lazy and idle. I confute them on that point. Take us generally as a people, we are neither lazy nor idle; and considering how little we have to excite or stimulate us, I am almost astonished that there are so many industrious and ambitious ones to be found; although I acknowledge, with extreme sorrow, that there are some who never were and never will be serviceable to society. And have you not a similar class among yourselves?

Again. It was asserted that we were “a ragged set, crying for liberty.” I reply to it, the whites have so long and so loudly proclaimed the theme of equal rights and privileges, that our souls have caught the flame also, ragged as we are. As far as our merit deserves, we feel a common desire to rise above the condition of servants and drudges. I have learnt, by bitter experience, that continual hard labor deadens the energies of the soul, and benumbs the faculties of the mind; the ideas become confined, the mind barren, and, like the scorching sands of Arabia, produces nothing; or, like the uncultivated soil, brings forth thorns and thistles.

Frederick Douglass  Rochester, New York, July 4, 1852

Rochester, New York, July 4, 1852

When he was invited by the Rochester Ladies Antislavery Society to deliver the annual Independence Day speech in 1852, Frederick Douglass addressed the issue of American slavery. In the tradition of New York State’s black community, he insisted on speaking on July 5. Blacks celebrated emancipation in New York State on July 5, 1827, after being urged by state legislators not to celebrate on the fourth when it took effect, since that day was revered by white citizens as their day of national independence.

Excerpt:

Fellow Citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of this republic. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were brave men. They were great men, too great enough to give frame to a great age. It does not often happen to a nation to raise, at one time, such a number of truly great men. The point from which I am compelled to view them is not, certainly, the most favorable; and yet I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration. They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory. . . .

Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here to-day? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? and am I, therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and to confess the benefits and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting from your independence to us?

Would to God, both for your sakes and ours, that an affirmative answer could be truthfully returned to these questions! Then would my task be light, and my burden easy and delightful. For who is there so cold, that a nation’s sympathy could not warm him? Who so obdurate and dead to the claims of gratitude, that would not thankfully acknowledge such priceless benefits? Who so stolid and selfish, that would not give his voice to swell the hallelujahs of a nation’s jubilee, when the chains of servitude had been torn from his limbs? I am not that man. In a case like that, the dumb might eloquently speak, and the “lame man leap as an hart.”

But such is not the state of the case. I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day? If so, there is a parallel to your conduct. And let me warn you that it is dangerous to copy the example of a nation whose crimes, towering up to heaven, were thrown down by the breath of the Almighty, burying that nation in irrevocable ruin! I can to-day take up the plaintive lament of a peeled and woe-smitten people!

“By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down. Yea! we wept when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof. For there, they that carried us away captive, required of us a song; and they who wasted us required of us mirth, saying, Sing us one of the songs of Zion. How can we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land? If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning. If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth.”

Fellow-citizens, above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are, to-day, rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them. If I do forget, if I do not faithfully remember those bleeding children of sorrow this day, “may my right hand forget her cunning, and may my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth!” To forget them, to pass lightly over their wrongs, and to chime in with the popular theme, would be treason most scandalous and shocking, and would make me a reproach before God and the world. My subject, then, fellow-citizens, is American slavery. I shall see this day and its popular characteristics from the slave’s point of view. Standing there identified with the American bondman, making his wrongs mine, I do not hesitate to declare, with all my soul, that the character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than on this 4th of July!

An etching from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper of 1877, with a caption that reads, “Washington, D.C.—The new Administration—Colored Citizens Paying Their Respects to Marshall Frederick Douglass, in his office at the City Hall.”

Marcus Garvey  studio recording, New York, July 1921

studio recording, New York, July 1921

This extract from a Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) membership appeal is one of only two known recordings of the voice of Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey, the organization’s founder and leader of the back-to-Africa movement. Garvey’s vision of a worldwide organization of black people united in their common struggle for freedom and dignity was partially realized in the UNIA, which had chapters throughout the black world.

Excerpt:

Fellow citizens of Africa, I greet you in the name of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League of the World. You may ask, what organization is that? It is for me to inform you that the Universal Negro Improvement Association is an organization that seeks to unite into one solid body the 400 million Negroes of the world; to link up the 50 million Negroes of the United States of America, with the 20 million Negroes of the West Indies, the 40 million Negroes of South and Central America with the 280 million Negroes of Africa, for the purpose of bettering our industrial, commercial, educational, social and political conditions.

As you are aware, the world in which we live today is divided into separate race groups and different nationalities. Each race and each nationality is endeavoring to work out its own destiny to the exclusion of other races and other nationalities. We hear the cry of England for the Englishman, of France for the Frenchman, of Germany for the Germans, of Ireland for the Irish, of Palestine for the Jews, of Japan for the Japanese, of China for the Chinese.

We of the Universal Negro Improvement Association are raising the cry of Africa for the Africans, those at home and those abroad. There are 400 million Africans in the world who have Negro blood coursing through their veins. And we believe that the time has come to unite these 400 million people for the one common purpose of bettering their condition.

The great problem of the Negro for the last 500 years has been that of disunity. No one or no organization ever took the lead in uniting the Negro race, but within the last four years the Universal Negro Improvement Association has worked wonders in bringing together in one fold four million organized Negroes who are scattered in all parts of the world, being in the 48 states of the American union, all the West Indian Islands, and the countries of South and Central America and Africa. These 40 million people are working to convert the rest of the 400 million scattered all over the world and it is for this purpose that we are asking you to join our ranks and to do the best you can to help us to bring about an emancipated race.

If anything praiseworthy is to be done, it must be done through unity. And it is for that reason that the Universal Negro Improvement Association calls upon every Negro in the United States to rally to its standard. We want to unite the Negro race in this country. We want every Negro to work for one common object, that of building a nation of his own on the great continent of Africa. That all Negroes all over the world are working for the establishment of a government in Africa means that it will be realized in another few years.

Marcus Garvey’s first UNIA International Convention, 1920, Harlem, New York

We want the moral and financial support of every Negro to make the dream a possibility. Already this organization has established itself in Liberia, West Africa, and has endeavored to do all that’s possible to develop that Negro country to become a great industrial and commercial commonwealth.

Pioneers have been sent by this organization to Liberia and they are now laying the foundation upon which the 400 million Negroes of the world will build. If you believe that the Negro has a soul, if you believe that the Negro is a man, if you believe the Negro was endowed with the senses commonly given to other men by the Creator, then you must acknowledge that what other men have done, Negroes can do. We want to build up cities, nations, governments, industries of our own in Africa, so that we will be able to have the chance to rise from the lowest to the highest positions in the African commonwealth.

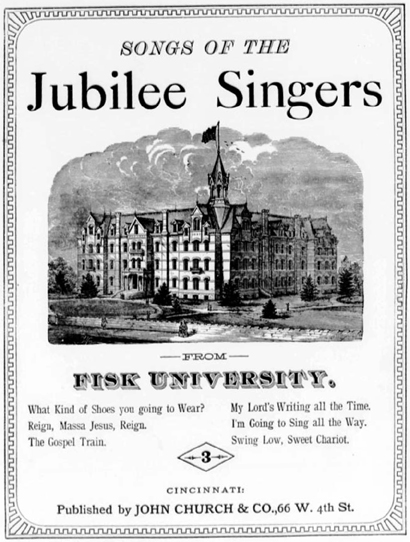

Cover of sheet music book, Songs of the Jubilee Singers from Fisk University, 1881.