The New Language of Vision

The social scientists of the Committee for National Morale were excellent theorists. They could articulate the nature of a democratic personality, of democratic morale, and of communication practices that might encourage both—in words. With the exception of Mead and Bateson, however, they lacked hands-on familiarity with the media technologies that could transform their ideas into visual modes of communication. For that, they would have to depend on another community: the refugee artists and designers of the Bauhaus. At the same moment in which American government officials and social scientists were focused on developing Americans’ will to confront fascism, the former members of the Bauhaus were busy integrating themselves into America’s intellectual and artistic elites. As they made their way in the New World, these artists turned the theoretical and practical tools they had developed in Germany toward the work of promoting American ideals and American morale.

Today the designers of the Bauhaus are perhaps best remembered for fusing art and technology and for spawning the mass-produced modernism that dominated the design of much American architecture, furniture, and advertising in the second half of the twentieth century. The glass-and-steel-box office buildings of Walter Gropius, the aluminum-tube chairs of Marcel Breuer, the simplified “universal alphabet” typescript of Herbert Bayer—each has become a ubiquitous memento of a time in which the artists of the Bauhaus glimpsed the possibility of an industrially manufactured utopia. When they established their school in 1919, however, the founders of the Bauhaus conceived of their project in terms that were simultaneously therapeutic and communalist as well as aesthetic. That is, they wanted their school to produce not only a new kind of design, but a new community of designers, and above all a new kind of person.

First, its founders hoped to train craftsmen who might integrate the many specialties associated with industrial design. Such transdisciplinary workers might then design material goods in such a way as to help break down the fractured, isolating social order of the modern industrial era and restore to its members a sense of community. Second, as part of that project, the founders of the Bauhaus hoped to transform the psychology of their students. The hyperspecialization of the industrial world had driven their students toward a psychological narrowness and an inability to integrate sensations, emotions, and analytical thought. Bauhaus teaching thus needed to help develop a student’s “whole personality.”1 Bauhaus products, too, would ideally promote the integration of the psyche. Whether in architecture, in photography, or on the stage, Bauhaus leaders created environments in which they required individual viewers to knit together a diverse array of visual experiences and so come to a coherent sense of the world around them and of themselves.

In 1933 the Nazis closed the Bauhaus, objecting to its members’ ostensibly degenerate penchants for abstraction and collectivism. By the end of the 1930s, many of the most prominent members had migrated to the United States. As World War II got under way, the former teachers of the Bauhaus, and particularly László Moholy-Nagy and Herbert Bayer, applied these techniques to helping make the personalities of American citizens more democratic and the nation as a whole more committed to confronting fascism. Drawing on tactics first developed to challenge the visual and social chaos of industrial Europe, they built environments—in books, in museum exhibitions, in classrooms, and in their own photographs, paintings, and designs—that modeled the principles of democratic persuasion that were being articulated by American social scientists at the same moment. These environments became prototypes for the propaganda pavilions that the United States government would construct overseas throughout the Cold War. Ultimately, they helped set the visual terms on which the generation of 1968 would seek its own psychological liberation.

THE BAUHAUS: TRAINING THE SENSES OF THE NEW MAN

To understand how former members of the Bauhaus might have turned toward the promotion of American morale in the early war years, and to understand why their aesthetics might have appealed to an American public not then known for its embrace of the European avant-garde, it is important to remember that from its earliest days the Bauhaus was preoccupied with creating what Walter Gropius called “the new human type of the future” and what Moholy called simply “the whole man.”2 At the professional level, this new man would integrate skills that had become the property of narrow specialists. Having done so, he would then be prepared to reintegrate form and function. He could do away with the frivolous decorations of nineteenth-century architecture and, for that matter, with his own frivolous attachment to the identity of the Romantic artist. “The work of the new man will become an organic part of unified industrial production,” wrote Gropius.3 And ideally, it would do for ordinary citizens what it had already done for the designer himself: restore their visual and thus psychological balance. The ultimate aim of the Bauhaus, Gropius later wrote, was to achieve “a new cultural equilibrium of our visual environment,” and so to improve the health and happiness of its inhabitants.4

For Gropius and the other early Bauhaus masters, the objects of industrial design and of art, plagued as they were by divisions between the functional and ornamental, mirrored the structure of the design professions, which had also become overspecialized. The gaps between specialties, in turn, mirrored a larger pattern of fractures in modern society and within the modern individual as well. Just as industrial society had detached individual artisans from the community of craftsmen, so the industrial world had driven modern individuals to let go of their own authentic impulses and of the natural unity between their sense-experience and their reason.

In the school’s early years, the professors of the Bauhaus hoped to heal all of these fractures simultaneously. The Bauhaus was to be a living example of a classless society of creative individuals. These workers were to create Gesamtkunstwerke—works of art that integrated multiple production techniques and spoke to the multiple perceptual faculties of their audiences. Nineteenth-century society had broken Germany apart; in the years after World War I the Bauhaus hoped to put it back together again, as a collective built around individual creativity and managed through design. “Let’s create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftsmen and artists,” they announced in a founding manifesto. “Together let us conceive and create the new building of the future, which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity which will rise one day toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.”5

For Gropius and his colleagues, the key to building a unified, classless society and to creating the whole man was design. To the founders of the Bauhaus, the Romantic artist, standing on the ramparts, daring society to return to an agrarian idyll, cut a ridiculous figure. So too did the artist’s mode of agency. In the Romantic account, an individual of genius reached into his soul, pulled forth some unique, indwelling bit of character, and gave it form in a singular work of art. The essence of the Romantic mode, as least as understood by the Bauhaus, was instrumental and individualistic: geniuses transformed spiritual raw material into polished art in order to express themselves. The Bauhaus mode, on the other hand, depended on an environmental model of power and a collective form of agency. As Gropius put it, many in the Bauhaus believed that “creative freedom does not reside in the infinitude of means of expression, but in free movement within its strictly legal bounds.”6 Unlike the Romantic artist, the Bauhaus designer would integrate himself into the industrial process—and accept its limitations on his range of expressive options. What he made would in turn set boundaries for the movement of individuals and so, paradoxically, free them to express themselves within society and not only as rebels against it.

Both the design of materials that might free their users and the training of designers themselves required an education of the senses. The professors of the Bauhaus did this work primarily in their required first-year course. The class was first taught by a mystic, Johannes Itten, and after 1923 jointly by Moholy-Nagy and painter Josef Albers. Under Moholy and Albers the course covered work in basic visual forms and in particular media: stone, wood, metal, clay, glass, color (conceived as a medium), and textiles. The workshop was not meant to be a ladder up which the student climbed toward a mastery of certain skills, though in part it did accomplish that. Rather, it was meant first and foremost to enable students to discover their own authentic interests and abilities—the inner core of their creative selves. “The preliminary course concerns the student’s whole personality,” explained a 1922 summary, “since it seeks to liberate him, to make him stand on his own feet, and makes it possible for him to gain a knowledge of both material and form through direct experience.”7

For the masters of the Bauhaus, the liberation of a student’s creative potential depended on his ability to recognize his affinity with some element of the world outside him and to choose to pursue it. Bauhaus publications of the 1920s routinely visualized this understanding by depicting the preliminary course as a circle, with the student implicitly at its center. In the first ring he would find new materials to work with: clay, stone, and the like. Beyond that, he would engage the abstract, elemental forms on which visual harmony depended. And still further out, in a third ring, he would encounter more traditional academic subjects: the analysis of nature, elements of engineering, and issues in what we would now call materials science. In each case, Bauhaus instructors would set these subjects out like a banquet and watch as individual students moved freely among them, choosing and so developing psychologically and professionally. To put it another way, at a curricular level the teachers of the early Bauhaus did not tell their students what to do so much as they created the conditions under which they could choose what to do from a cafeteria of options. Students could thus find their way to authentic free expression of their innermost selves, but in terms set by the needs of industry and society. At the same time, students could also integrate their exposure to various skills into their professional practices, and their exposure to different sensations into their personalities. They could, in short, become whole.

Of all the senses addressed in the preliminary course, the one that would go on to have the greatest impact on Americans in search of morale was vision. In the years before the Bauhaus instructors moved to America, two who would have an extraordinary influence here—Moholy and Bayer—developed modes of visual display that echoed the experiential ideals of the preliminary course. In the first mode, which he called the “New Vision,” Moholy mingled the utopian ideals and montage aesthetics of Russian Constructivism with new photographic and typographic techniques to produce a wildly vertiginous aesthetic. In the second, which built on both Moholy’s work and its Constructivist origins, Bayer developed a new mode of museum display. Whereas museums had traditionally hung images at eye level, Bayer began to enlarge photographs and words, to hang them above and below the viewer’s line of sight, and so to expand the viewer’s array of visual choices.

These techniques would become tools for democratic modes of propaganda during and after World War II for two reasons. First, artists like Moholy and Bayer had to make a living in mid-century America, and to do so, they aggressively applied the techniques they brought with them to intellectual and professional opportunities they found here. Second, Moholy’s “New Vision” and Bayer’s “field of vision” techniques solved a problem for American promoters of morale. If fascist communication worked instrumentally and molded individuals into a single, unthinking mass, these Bauhaus modes of seeing were designed to do the reverse: like the preliminary course, they demanded that individuals reach out into an array of images and knit them back together in their own minds. In the process, they could reform both their own fractured psyches and, potentially, society itself. For Moholy and Bayer, as for Gropius, art and the technologies of artmaking offered environments in which individuals could experience themselves as simultaneously more completely individuated and more integrated into society.

LÁSZLÓ MOHOLY-NAGY AND THE NEW VISION

As a young man, Moholy embraced Russian Constructivism and, with it, the notion that making art meant making social revolution.8 A painter and graphic designer born and raised in Hungary, Moholy left Hungary in 1919 and moved to Berlin, where he travelled in circles that included Dadaists, various modernist literati, and the Russian Constructivists El Lissitzky and Naum Gabo.9 Together, the Constructivists turned away from academic realism and toward the construction of abstract forms. They were to imitate the shapes of industry if they imitated any shapes at all, and they were to make their peace with machines. “To be a user of machines is to be of the Spirit of the Century,” wrote Moholy in 1922. “Before the machine, everyone is equal. . . . This is the root of socialism, the final liquidation of feudalism.”10 For Moholy and other Constructivists, to create abstract assemblages was to turn the senses and the intellects of their viewers toward utopia. Theo van Doesburg, a Dutch artist living in Berlin at the time and a friend of Moholy, celebrated the Constructivists’ goals in a 1921 manifesto: “Theirs is the language of the mind, and in this manner they understand each other. . . . The International of the Mind is an inner experience which cannot be translated into words. It does not consist of a torrent of vocables but of plastic creative acts and inner or intellectual force, which thus creates a newly shaped world.”11

Moholy brought this twinning of psychological and social revolution to the Bauhaus when he joined the faculty and began teaching its preliminary course in 1923. Under the previous instructor, Johannes Itten, the preliminary course had included exercises in breathing and meditation as well as craft technique.12 Under Moholy, the course lost its mystical tone but retained Itten’s insistence on the unity of artistic and psychological development. That fusion, Moholy believed, could transform the organization of society. “Through technique man can be freed, if he finally realizes the purpose: a balanced life through free use of his liberated energies,” wrote Moholy some years later.13 Technique, he suggested, could help individuals bring together the senses of their biological organisms and the critical impulses of their reasoning minds. Thus strengthened, individuals could resist the imperatives of received authority and the demands of narrow specialists. They could find what Moholy called “a plan of life which places the individual rightly within his community.”14

Moholy taught at the Bauhaus from 1923 to 1928. Outside the classroom in the same years he explored photography, typographic montage, and the sculptural powers of light. These new modes of communication represented a qualitative break from the realistic representation offered by painting, he believed. Photography in particular made it possible for a person to see objectively for the first time. No longer would the viewer have to behold the world through the sensibility of the painter. Instead, the camera could so automate vision as to extend the viewer’s senses in the direction of reason: “The camera is the objective presentation of facts,” Moholy explained, and so “makes [the onlooker] more apt to form his own opinions” about reality.15 As such, the camera could become an instrument of public mental health: thanks to its objectivity, wrote Moholy, “the hygiene of the optical, the health of the visible is slowly filtering through.”16

For Moholy, as for a range of American critics in the 1920s and 1930s, the mass media were enemies of visual and mental health. In a 1934 letter to his Hungarian friend and sometime editor Frantisek Kalivoda, Moholy explained that “a widely organized and rapid news service today bombards the public with every kind of news. . . . Without interest in evolution it overwhelms its public with sensations. If there are no sensations, they are freely invented or deliberately improvised.” The average newspaper reader encountered its daily texts with little more than a mild interest, Moholy believed; its stimuli made the reader numb.17 In his attack on newspapers and radio, Moholy identified an instrumental mode of communication much like the one that American critics of the late 1930s would associate with German propaganda. In his view, mass media sent out messages to which readers responded like puppets: they became unable to think and unable to resist the authorities around them.

Moholy’s critique of the mass media contained within it an implicitly Freudian understanding of the mass media’s power. In his account, mass media stimulated the internal regions of the psyche in ways of which the individual was unconscious. By contrast, his own work manifested a Gestaltist understanding of the mind. In this view, perception itself became the means by which a person created his or her inner life. As in the field psychology of Kurt Lewin or the personality theories of Gordon Allport and the neo-Freudians Horney, Stack Sullivan, and Fromm, Gestaltists like Moholy believed that the person was always a work in progress, and that the individual psyche changed and grew in relation to the environment around it. This process depended on the ability of the person to apprehend that environment through the sense organs—the eyes, ears, nose, fingertips, and tongue. It was the senses, after all, that tugged on the individual threads of experience and drew them inward to be woven into the psyche.

For Moholy, media technologies could serve as extensions of the sense organs. The 35-millimeter camera, for example, enabled viewers to extend their range of vision. As it did, it presented viewers with opportunities to become more conscious of their places in space and time. When they looked at his photographs, and so in a sense looked through his camera’s lens, Moholy believed his viewers could not only see more of the world around them, but integrate what they saw into a more complete picture of reality.

Moholy’s photographs showed little resemblance to the straight documentary gaze that Americans would associate with “reality” in coming years. On the contrary, he aimed his lens downward from dizzying towers and outward through patterns of girders. He made strange patterns of objects on paper, called photograms, that seemed to be half X-ray and half ghost. He also began to mingle typographic designs with photographic imagery in a style he called “typophoto.”18 Like his photographs, his typophoto images transformed two-dimensional surfaces into seemingly three-dimensional environments. They were not pictures of a three-dimensional world so much as worlds unto themselves. Moholy’s desire to spatialize visual experience extended to his work with light. For Moholy, light did not simply illuminate the material world; it could be a materially structuring force in its own right. Light could surround individual people and free their senses to such a degree that they could finally comprehend their places in the universal space-time continuum.19 In a 1917 poem, Moholy foreshadowed the ecstasies of the countercultural light shows of the 1960s when he exclaimed, “Light, total light, creates the total man.”20

In 1928, Moholy published a volume in which he summarized his ideals and which in its design exemplified them, The New Vision. The volume outlined the stages of the preliminary course as Moholy taught it, and it included photographs of students’ work. But it was much more than an aesthetic primer. According to Moholy, it was a guide to human evolution. Before the industrial era, he argued, “primitive man” had used all of his faculties constantly.21 Now he had to specialize. As a result, he could no longer see reality whole, nor could he see, feel, and think simultaneously. The preliminary course at the Bauhaus aimed to restore those abilities; so too did The New Vision. In its pages, photographs and text mingled promiscuously. Photographs might be straight documentary images, or they might be montages. Text might be ordinary, bold, or a mixture of the two. And the images depicted everything from tabletop constructions to the frame of a dirigible. Taken as a whole, the book was more collage than linear text. Like the preliminary course, it offered readers a way to stand in a circle of visual and textual signs, selecting those that engaged them, and pulling them together into a whole and substantially enlarged view of their place in the world.

HERBERT BAYER AND THE EXTENDED FIELD OF VISION

The New Vision was translated into English and republished soon after Moholy migrated to America in 1937, and it went on to have an extraordinary influence on American photography and design. In the years in which he was writing it, though, Moholy’s visual tactics and the Constructivist ideals they embodied had a substantial influence on a Bauhaus student and later instructor, Herbert Bayer. Born in Vienna in 1900, Bayer came to the Bauhaus as a student in 1921. He had read Wassily Kandinsky’s book Concerning the Spiritual in Art, in which Kandinsky called for a new kind of art, one that would turn away from materialist concerns and toward the cultivation of spirituality in its makers and its audiences. Bayer mistakenly believed that Kandinsky was already teaching at the Bauhaus (he wouldn’t join the faculty until 1922) and he hoped to study with him.22 Bayer stayed at the Bauhaus until 1923, traveled for a year, and then returned to the Bauhaus as the head of the typography workshop. He would teach there until 1928.

As an instructor at the Bauhaus, Bayer absorbed the aesthetic theories of his colleagues, and especially Moholy, as well as their social-utopian and pro-industrial orientations.23 Before Bayer took over the typography workshop, it had focused on hand printing and small-scale letterpress work.24 Bayer quickly found industrial printing gear and oriented the students’ work in a more pre-professional direction. At the same time, he turned his own work in the direction of Moholy’s typophoto aesthetics. Like Moholy, he aimed to make type easier for readers to read and for printers to work with. He thus turned away from the Gothic German script of the period and developed the “universal alphabet” that would become a hallmark of Bauhaus publications after 1925.25 At the same time, he experimented with ways in which to combine typography and photography and to spatialize the two-dimensional picture plane. His posters for Bauhaus dances, for example, layered images and text one on top of the other in ways that transformed the surface of the paper into a well in which the visual elements of Bayer’s compositions seemed to float at different depths. Even his more two-dimensional works such as letterheads featured a geometric, architectural sensibility. His images and texts did not look as if they had been drawn or even printed; they looked as if they had been built.

Such designs matched well with both Bauhaus director Gropius’s emphasis on architecture and Moholy’s Constructivist ideals. Just how well would not become clear, however, until all three had left the Bauhaus. In 1930, art critic and curator Alexander Dorner asked Walter Gropius to organize Germany’s contribution to the pan-European Exposition de la Société des Artistes Décorateurs at the Grand Palais in Paris.26 Gropius in turn commissioned former Bauhaus colleagues Bayer, Moholy, and Marcel Breuer to assist him. Together they designed a “community center” to be included as part of an apartment building.27 Gropius designed the public spaces; Breuer furnished an imaginary apartment; Moholy created exhibitions of stage and ballet materials, architectural photography, and lighting fixtures. Bayer created installations of everyday objects that could be mass-produced.

Conventional exhibition practice of the time suggested that Bayer should arrange his objects and images either at eye level or as they might be seen in an actual living room. Building on the Gestaltist visual sensibility outlined in Moholy’s New Vision, as well as in an earlier exhibition by El Lissitzky, Bayer took a radically different tack. As he prepared the blueprints for his part of the exhibition, he drew a picture of man whose head was nothing but a giant eyeball. In front of the man he drew some seventeen screens—some arrayed at eye level, but others angled down from the ceiling and still others angled up from the ground. Entitled “Diagram of Field of Vision,” the image was later reprinted in a catalog of the exhibition. It also became the basis of Bayer’s installation for the Paris show. In his gallery of furniture and architecture, Bayer hung rows of chairs from the walls and arrayed enlarged photographs of buildings in front of, above, and beneath the eyes of the spectator.

By today’s standards, such an innovation might seem mild, even trivial. In a time in which digital screens bombard us with images from every conceivable angle and in places as diverse as football stadiums, airplanes, and bedrooms, it is difficult to imagine how important Bayer’s new strategy actually was. In essence, he had found a way to transform Moholy’s New Vision into a three-dimensional environment. In the early 1920s, fans of the Bauhaus or of Moholy might have celebrated the ways in which they blended text and image to create the illusion of depth on the page. But in Paris, Bayer created something that was no illusion; it was an actual, three-dimensional space into which the viewer could walk. Five years later, he extended that environment to include the ground below the viewers’ feet and the area over their heads. In 1935, Bayer worked again with Gropius, Breuer, and Moholy, this time to construct the Baugewerkschafts Ausstellung (Building Workers’ Unions Exhibition) in Berlin. Once again, he designed an environment that would extend the range of the visitors’ visual field. And once again, as he planned, he drew a man whose head had been transformed into an eyeball. This time though, the viewer stood on a slightly raised platform and screens surrounded him on all sides. They looked up from below and down from above. They hung in front of him and behind him. In this new drawing, the visual field and the three-dimensional world itself were virtually contiguous.28

In both exhibitions, the material world of chairs and buildings had been transformed into a semiotic universe. Wrenched from their ordinary, everyday physical places, chairs on the wall and oversized photographs became a kind of three-dimensional typescript. But they produced no message, no instrumental instructions for their viewers. Rather, like Moholy’s photomontages, or like the different materials from the preliminary course at the Bauhaus, they offered observers the chance to identify and integrate into their psyches those elements of the visual field they found most meaningful. By the mainstream standards of the time, hanging chairs on the wall might have looked like a bit of visual cacophony; yet in the context of the New Vision, it gave viewers the chance to synthesize their perceptions and so create in themselves a state of visual and emotional balance. If mass media tended to trigger the unconscious desires mapped by Freud and thus make viewers numb, the displays pioneered by Bayer were meant to make museumgoers active synthesizers of the world around.

FIGURE 3.1.

Herbert Bayer, “Diagram of 360 Degrees of Vision,” 1935. © 2011 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Part of the appeal of Bayer’s work for Americans grew out of the ways in which Bayer situated his installations in relation to the two political extremes of avant-garde display in the 1930s: the communist and the fascist. Bayer was not the first designer to enlarge photographs or to array them top to bottom on a wall. In 1928 he had attended the International Press Exhibition in Cologne, where he saw El Lissitzky’s massive photo mural “The Task of the Press Is the Education of the Masses” in the Soviet pavilion, as well as photographs hung on wires dropped from the ceiling and towering pillars bedecked with images. Bayer later recalled that it was Lissitzky’s installations that inspired him to take up exhibition design.29 At the same time, however, he thought Lissitzky’s design was “chaotic.”30 Though Bayer adopted Lissitzky’s environmental orientation, he fused it with a Gestaltist visual sensibility and, beyond that, a desire for artistic control. “An exhibition can be compared with the book,” he later wrote, “insofar as the pages of the book are moved to pass by the reader’s eye, while in an exhibition the visitor moves in the process of viewing the displays.”31

Though Bayer thought of himself as an author and, in that sense, sought to control his audience’s movements and point them to certain conclusions, he was also careful to leave plenty of room for the reader to interpret his text. “The physical means by which the content of exhibits is brought to the attention of the visitor should not in themselves be autocratic or domineering,” as he later put it.32 In the 1930s, utopian Constructivists were not the only ones staging spectacular exhibitions. Fascists, and particularly Italian fascists, were equally fascinated by the power of surrounding viewers with images to influence their ideals. Like Bayer, they arrayed images from floor to ceiling in such a way that they required viewers to crane their necks to see what was above them, or to peer down to their toes to see the imagery there.

Yet despite the fact that they shared a totalizing, environmental orientation toward display, Bayer’s images extended the viewer’s field of vision to present a distinct alternative to fascist aesthetics, politics, and psychology. In 1932, for instance, the Italians mounted a massive exhibition in Rome to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the fascists’ march on the Italian capital.33 Along one wall, designer Giuseppe Terragni installed a huge photomontage that featured many of the elements common to El Lissitzky’s pro-communist imagery: large crowds, a blending of text and image, a mix of abstraction and realism. But far from offering the eye a set of images for the viewer to bring together in his own independent mind, as Bayer recommended, Terragni’s wall did the work of integration on behalf of the viewer. As the viewer moved from right to left along the wall, he saw crowds of individuals slowly morph first into turbines and then into an abstract field of hands raised in the fascist salute.

Like Bayer—and, for that matter, like Moholy, Gropius, and many at the Bauhaus—fascist designers like Terragni were preoccupied with the relationship of the individual to the social whole. But unlike their Bauhaus counterparts, the fascists sought to de-individuate their viewers and help them join the undifferentiated social mass that they believed to be the source of their political power. Bayer, on the other hand, had designed his exhibitions to resemble books. Each image was a separate page, cut off from the others by a bit of space across which the viewer would need to make both a physical and perceptual leap. Bayer’s images needed interpretation and integration into a larger narrative. Fascist exhibitions presented looming environments dominated by a single idea: the people should be one, fused into a single engine-like machine, empowering and empowered by their leader. To disappear into the crowd was a glory. Bayer’s work, in contrast, arrayed a mass of carefully separated individual images. It asked viewers to move from picture to picture, to recognize those of particular value to themselves, and to choose to integrate them into their own individual psyches. If fascist artists encouraged viewers to turn their individual agency over to dictators, Bayer encouraged his viewers to practice psychological self-sufficiency as they chose dishes from the visual banquet he had laid out. If the fascists hoped to dissolve the individual into a single social whole, Bayer, like Moholy and the founders of the Bauhaus, aimed to build a diverse social collective out of psychologically complete individuals.

FIGURE 3.2.

Giuseppe Terragni, Tenth Anniversary Exhibit of the Fascist Revolution, Sala O, a 1932 installation dedicated to the 1922 fascist march on Rome. The exhibit (“Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista”) was held in the Palazzo delle Esposizioni on the Via Nazionale in Rome.

THE NEW VISION COMES TO AMERICA

In the late 1930s, Bayer was working as a creative director at an advertising agency in Berlin. In 1936, the Ministry of Propaganda demanded that he insert a picture of Hitler in an exhibition catalog; later that year, they required a two-page photomontage celebrating the Nazified nation.34 While Bayer himself wasn’t Jewish, his wife and daughter were, and so were many of his clients.35 He began to seek a way to leave the country. So too did Moholy, Gropius, and many other former Bauhaus faculty. They soon became part of an extraordinary migration of German intellectuals and artists that would transform American social thought and American art.36

As the veterans of the Bauhaus arrived in an America that still struggled with economic depression, deep racism, rampant demagoguery, and increasingly, a fear of war, they found that their earlier preoccupations could be made to serve new ends. Their fascination with the role of the individual in industrial society became a fascination with self-actualization in democratic society. Their critiques of industrial bureaucracy took on an antifascist tinge. And perhaps most powerfully, Bayer and Moholy began applying the same techniques that had been aimed at making the personalities of Bauhaus students whole toward promoting American morale and, once American troops entered combat, toward helping veterans recover from its effects. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, aesthetic strategies rooted in socialist utopianism became tools with which to make a more democratic America.

Moholy began to articulate his utopian aesthetic agenda in American terms almost as soon as he arrived. In 1937 a group of Chicago businessmen known as the Association of Arts and Industries invited Walter Gropius to establish a design school in their city. Gropius recommended Moholy for the job and in summer of that year, Moholy moved to the American Midwest.37 In August he wrote to his wife Sybil, “You ask whether I want to remain here? Yes, darling, I want to remain in America. There’s something incomplete about this city and its people that fascinates me; it seems to urge one on to completion. Everything seems still possible. The paralyzing finality of the European disaster is far away. I love the air of newness, of expectation around me. Yes, I want to stay.”38

With the support of the Association, Moholy established the New Bauhaus, and on October 18, 1937, he admitted some thirty-five students. The opening drew nationwide press coverage. Reporters celebrated Chicago’s embrace of the forward-thinking Bauhaus modernists whom Hitler had rejected. Few Americans, however, quite grasped the socialist inclinations of the original Bauhaus.39 Nor did they have to. Even as he reinstituted much of the original Bauhaus curriculum, Moholy reframed its mission in American terms. “Now a new Bauhaus is founded on American soil,” he announced in a new American edition of The New Vision (italics original). “America is the bearer of a new civilization whose task is simultaneously to cultivate and to industrialize a continent. It is the ideal ground on which to work out an educational principle which strives for the closest connection between art, science, and technology.” Having linked the intellectual mission of the German Bauhaus to the practical, industrial orientation of the school’s original backers, Moholy went on to stress the importance of personal psychological development. “To reach this objective one of the problems of Bauhaus education is to keep alive in grown-ups the child’s sincerity of emotion, his truth of observation, his fantasy and his creativeness.”40

As he established the New Bauhaus, Moholy dropped the socialist rhetoric of his youth but preserved its techniques: the New Bauhaus, like the old, would be a place for personal transformation. Once again, craftsmen would integrate skills, work to become whole people, and develop a community of shared labor. But this time, they would become part of a long American tradition. “The characteristic pioneer spirit which we find unimpaired in our American students” equipped them well to invent new visual and social forms, he explained.41 As once he had hoped that the abstract constructions of German students would help them glimpse utopia, so now he argued that the works of his new American students exemplified traditional American ideals. He printed images of their work alongside his own; they too, he argued, had obtained a new way of seeing. But this time the future they glimpsed had a nationalist cast.

Moholy’s embrace of things American increased as Hitler’s armies swept across Europe. In a 1940 article entitled “Relating the Parts to the Whole,” Moholy argued that design schools offered the kind of training that would strengthen individual American character and American society as a whole in the face of fascism. His case is worth quoting at length:

THE PRESENT WORLD CRISIS will bring unforeseen problems to all of us. We shall have to make decisions of great consequences, both to ourselves and to the nation. Whether or not Hitler wins, whether or not we get into the war, we shall undergo great strains because an equilibrium has been disturbed. Europe has lost the leading position which it had in culture and technics. America is now the country to which the world looks.

AMERICANS, A MOST RESOURCEFUL PEOPLE in technology and production, have in one respect over-done specialization. Processes and institutions have developed which, however ingenious, are wasteful because they are poorly related, each to the other.

WE NEED IN LARGE NUMBERS a new type of person—one who sees the periphery as well as the immediate, and who can integrate his special job with the great whole of which it is a small part. This ability is a matter of everyday efficiency. It will also contribute to building a better culture [capitalization original].42

Moholy’s account clearly marks his own attempt to market Bauhaus training and theory to an America on the brink of war. At the same time, though, it offers a new way to meet the psychological challenges posed by the theorists of the Committee for National Morale. Like psychologist Lawrence Frank, Moholy here recasts the battle against fascism as a battle for personality. By creating a new kind of person, endowed with a new kind of sight, Americans can build not only a more efficient society, but a better one. From a distance of half a century, Moholy’s language may look curiously abstract. But in the context of American society at the end of the 1930s, that abstraction made it possible to point to the ferocious racial, regional, economic, and political divisions plaguing American society without naming them. Moholy could simultaneously acknowledge problems in American society, obscure their social-structural roots, and shift the site of their solution from the governmental to the personal level. In other words, like the psychologists and sociologists of the Committee for National Morale, Moholy found a way to transform political problems into psychological ones.

In Moholy’s thinking, the practice of design in turn became the link between the making of better selves and the making of a better America: “A designer trained to think with both penetration and scope will find solutions, not alone for problems arising in daily routine, or for development of better ways of production, but also for all problems of living and working together. There is design in family life, in labor relations, in city planning, and living together as civilized human beings. Ultimately all problems of design fuse into one great problem of ‘design for living,’” he wrote. His own school in Chicago served as a prototype both for the teaching of this new way of changing the world and for the kind of world such teaching might produce. It modeled, “on a small scale, what might happen on a large scale as the ability to think and work relatedly extends,” he explained.43

THE EXTENDED FIELD OF VISION AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

At the same time that Moholy was working to Americanize the New Vision in Chicago, Herbert Bayer was bringing his extended field of vision to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The museum had been founded in 1929 by three society doyennes, the most prominent of whom was Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, wife of John D. Rockefeller and mother of future vice president Nelson Rockefeller. It quickly became a primary gateway for European art and artists seeking entry into the United States. In its first ten years it helped introduce Americans to impressionism, Futurism, and cubism, as well as to modern architecture, photography, and typography. In 1939 after Hitler invaded Poland, its director, Alfred Barr, and his wife immediately launched an effort to rescue avant-garde artists. With the prestige of the museum and the Rockefeller family name behind them, they managed to help bring half a dozen leading figures to the United States, including Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, and Jacques Lipschitz. Even before Pearl Harbor, Barr and the Rockefellers began to transform the museum into an engine of ideological production that would support American propaganda efforts across the Cold War.

Herbert Bayer’s extended field of vision would play an important role in that process. Bayer first came to the Museum of Modern Art at the invitation of John McAndrew, the museum’s curator for architecture and industrial art. In the summer of 1937, the museum was planning to mount a comprehensive historical exhibition of the Bauhaus’s work from 1919 to 1928. In those same months, Bayer and Marcel Breuer were visiting the United States with an eye to preparing for emigration. They joined Gropius, Moholy, McAndrew, and others for a meeting to discuss the upcoming exhibition, and by the end of it, Bayer had been enlisted to design the show.44 Bayer then returned to Germany to help find Bauhaus artifacts and ship them to New York. The materials that he and Gropius gathered spanned the panoply of Bauhaus productions. They included paintings, sculptures, photographs, drawings for stage sets, and typophoto posters. They also featured shiny Bauhaus tea sets, Marcel Breuer’s aluminum-railed armchairs, and even an architectural model of the Gropius-designed Dessau Bauhaus. When the show opened on December 7, 1938, it was the most complete representation of the early Bauhaus seen outside of Germany.

For American art critics, the most surprising element of the exhibition was not its content but its installation. Because the Museum of Modern Art was then constructing a new home for itself at 11 West 53rd Street in Manhattan, Bayer installed the show in the museum’s temporary space in the concourse of Rockefeller Center. He and Gropius broke the show up into six sections, each with its own gallery: “The Elementary Course Work,” “The Workshops,” “Typography,” “Architecture,” “Painting,” and “Work from Schools Influenced by the Bauhaus.”45 Bayer then transformed these areas into variations of the extended visual environments he had built in Paris in 1930 and in Berlin in 1935. In Berlin, Bayer had been unafraid to attach chairs to the wall. Here, he became more conservative, confining furniture to the floor and most images to a range fairly near eye level. At the same time, however, he transformed the galleries of Rockefeller Center into spaces that would surround viewers with visual information and guide their experience of the exhibition.

As viewers entered the first gallery, they encountered Lyonel Feininger’s painting Cathedral of Socialism—an image that had been printed alongside the first manifesto of the Bauhaus in 1919. The painting hung by strings from the ceiling. Moving from room to room, viewers found footprints on the floor and graphic hands on the wall, pointing them to new parts of the exhibition. A giant egg hung from one wall, representing a teaching form from the first-year curriculum. Photographs arched downward from overhead; diagrams of color wheels dangled from the ceiling. In one room a giant eye stared outward from the wall at the viewer from underneath a slot. When the viewer peered through the hole in the wall, he saw a cluster of spinning, humanoid automatons in costumes created by Bauhaus theater master Oskar Schlemmer. Finally, throughout the exhibition, Bayer had painted the floor in geometric shapes, as if it too were an abstract construction.

From the point of view of early Bauhaus ideology, Bayer’s design transformed the exhibition into a Gesamtkunstwerk. In accord with his theories of the extended field of vision, it surrounded viewers, gently nudging them here or there, encouraging them to go with the flows painted on the walls and floors. In keeping with the Gestaltist psychology underlying Bayer’s theories, viewers would need to synthesize the elements presented to them into coherent internal pictures of their own. The exhibition itself could suggest, could present, could house and frame—but viewers would ultimately have to put together their own pictures of the Bauhaus as a whole.

In 1938 more than a few viewers found this degree of agency disconcerting. Some seventeen thousand visitors passed through the museum during the show’s seven-week run.46 Museum records suggest that many in the audience especially enjoyed seeing everyday objects designed by the Bauhaus, and that response to the show among the broad public was quite favorable.47 The exhibition set off something of a firestorm among art critics, though. Some, most notably Lewis Mumford in The New Yorker, applauded the show and the work of the Bauhaus more generally.48 Many appreciated the individual works on display. But in a report for museum trustees, Alfred Barr noted that many who admired the work of the Bauhaus found the exhibition installation confusing.49 The New York Times critic Edward Alden Jewell, for instance, praised the Bauhaus for its forward-looking designs but condemned the exhibition as “chaotic,” as “voluminously inarticulate,” and as suffering from “disorganized promiscuity.”50

Not every critic agreed with Jewell. But his review serves as an important chronological marker. In 1938, even some of the most experienced museumgoers in America found Bayer’s extended field of vision techniques utterly alien. Since most American critics lacked the utopian impulses of the early Bauhaus, its faith that a change in perception could change the social order, and even a basic familiarity with Gestalt psychology, few saw the need to knit together their own visual experiences from a visual surround as being a liberating experience. On the contrary, they found themselves at sea.

Only a few years later, however, as the Museum of Modern Art became a central hub for the boosting of American morale, critics came to see the flexibility and independence that Bayer offered his viewers, coupled with his environmental mode of governing the viewers’ movements, as a uniquely pro-American mode of propaganda making. Bayer’s extended field of vision solved the problem posed by fascist propaganda and mass media: by granting viewers high degrees of agency with regard to the visual materials around them, and by at the same time controlling the shape of the field in which they might encounter those materials, the extended field of vision could lead American viewers to remake their own morale in terms set by the field around them. That is, they could exercise the individual psychological agency on which democratic society depended, and so avoid becoming the numb mass men of Nazi Germany. At the same time, they could do so in terms set by the needs of the American state, articulated in the visual diction of the Bauhaus.

In the years between its Bauhaus 1919–1928 exhibition and Pearl Harbor, the Museum of Modern Art became an extraordinary forum for the development of pro-democratic propaganda and for debates about what forms it should take. In 1939, the museum’s board appointed Nelson Rockefeller president of the museum; within a year, he would serve as President Franklin Roosevelt’s point man in the effort to keep Latin America from supporting the Axis. The board also soon included Archibald MacLeish, the librarian of Congress and occasional speechwriter for President Roosevelt, who would go on to briefly help lead America’s wartime propaganda efforts as director of the deceptively blandly named Office of Facts and Figures. Roosevelt himself acknowledged the museum’s importance as a bulwark against fascism when he gave a radio address celebrating the opening of the museum’s new building on May 10, 1939. The museum, he explained, would be an emblem of freedom, artistic and political. “The arts cannot thrive except where men are free to be themselves and to be in charge of the discipline of their own energies and orders,” he said. “The conditions for art and democracy are one and the same.”51

In June 1940, Abby Rockefeller had become incensed by the fall of Paris and the rise of Mussolini in Italy, and sought to create an exhibition that would awaken isolationist Americans to the dangers they posed.52 She recruited the museum’s director, Alfred Barr, writer Lewis Mumford, librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish, and eminent curator Leslie Cheek to design the show. They and several others labored for four months to craft an enormous, immersive multimedia environment that would persuade Americans to take action. The project was known first as Exhibition X and later as For Us the Living. In their scenarios, the authors proposed to double the museum’s floor space by constructing an entirely new building to house the exhibition. Cheek wrote, “Into this carefully designed structure would go the display, which was really an ‘experience’ through which groups of the public were to be taken, via an automated taped voice, through a series of areas of varying size, color, texture, lighting, smell, and sound to view the displays of illumined texts, movies, mannequins, motion pictures, etc.”53

The drafts of scenarios that remain in the museum’s archives reveal that Cheek and his colleagues hoped to immerse their audiences in what they called a “drama.”54 They imagined dividing their building into a series of thirteen halls, which they called “scenes.” The viewer would enter a “waiting room” with questions written in giant letters on the wall:

Will I have a job tomorrow?

Dare we have children?

Will democracy hold its own against fascism?

What would life be like in an undemocratic and enslaved world?”55

Thus primed, viewers would hear a voice on a loudspeaker inviting them to enter the next room. There they would see projections of America and Europe at peace. They would listen to a narration, backed by music, of American history. Suddenly a voice would announce: “And now, today, November 15, 1940, every man and woman in this room faces a crisis. We must choose between (music stops, dramatic pause by voice) Democracy and Freedom or Fascism and Slavery.”56 Hidden projectors would then post an image of Lincoln on one wall and a portrait of Hitler on another.

The authors continued in this vein as they drew visitors first down the “Avenue of Fascism”—a hall lined with dummies dressed as storm troopers, workers, mothers, and children—and into an imaginary fascist future. Having frightened their visitors with that possibility, the authors then welcomed them to the “Hall of American Character.” “This room is an esthetic and emotional contrast to the dynamic humbug of the faceless men,” wrote the authors. “It is quiet, assured, full of character. . . . It is lined on both sides with pictures of Americans, of uniform size; portraits of head and shoulders.” These would be “pictures of real people, with real biographies . . . drawn from each state.” Together they would represent “the essential principle of democracy—the worth of the individual personality.”57

These images would also introduce visitors to halls featuring the history of the American people and their achievements before sending them on to confront “the job in hand.” This included not only confronting Hitler, but remaking American democracy so that it would be something worth confronting Hitler with. The authors advocated four principles, which they labeled “goals for tomorrow” and proposed to post as signs reading “Rededication to Natural Resources,” “Transformation of Work,” “Renewal of Family and Personality,” and “Revitalizing of Democratic System [sic].”58 Thus sequenced, the goals served as a road map out of the Depression and toward the strengthened faith in the nation that was required by the impending war. Finally, the show’s designers released visitors into the final exhibition room, the “Hall of Human Values.” There they would stand on a balcony, gazing down onto “a great, simple room, flooded with cool light and fine music.” Across from the balcony they would see gigantic tablets, each with a bit of wisdom from “the high religions and philosophies of mankind,” and a sign illuminating “the highest goal of effort: Rededication to the Enduring Truths and Values of Mankind.” Ideally, wrote the authors, visitors would experience feelings of “composure and elevation, too deep for mere brassy self-confidence and egoistic national assertiveness, but capable of being translated into sustained thought and action.” Upon leaving the hall, they might even be confronted with tables soliciting their active support for the antifascist Allies—and thus, an opportunity to benefit all mankind.59

In all of these ways, the designers of For Us the Living hoped not only to strengthen Americans’ faith in their democracy, but to prepare the nation to go to war. The discussions at the Museum of Modern Art that surrounded their work, however, reveal a deep distrust of propaganda, and of instrumental communication more generally. When Alfred Barr presented the group’s scenarios to the museum trustees in July 1940, he explained that they had designed the exhibition to show that Americans had a responsibility to confront fascism. At the same time, he argued, it would “ostensibly not be a propaganda exhibition.”60 That is, it would lead visitors to certain views, but do so in a way different from both the propaganda masters of Nazi Germany and the American propagandists of World War I. Leslie Cheek seconded this view. Even as he described the exhibition as a drama and structured it like one of the most prominent and most suspect mass media, a film, Cheek argued that the exhibition would not overwhelm viewers or deprive them of agency. “In this exhibition, the visitor is not a passive spectator but an actor; and the aim of it is to indicate the character and scope of further activity that demands his participation as a citizen.”61

In other words, Cheek argued that the exhibition served as a space in which viewers could practice the skills on which the future of democracy depended. But Abby Rockefeller was having none of it. In October 1940, she and the board turned the project down flat. In part she must have objected to the exhibition’s $750,000 budget—though if she did, she didn’t say so. In a letter to Cheek, she explained that she would not support the exhibition because to her it seemed too much like a movie.62 Rockefeller didn’t expand on the point, but in 1940 America she didn’t have to. For those concerned with propaganda, movies smacked of the instrumental mode of communication employed by Hitler and Mussolini. They seemed to work as dictators did, by turning off the reason of their viewers, by making them numb and obedient. This exhibition, Rockefeller implied, was trying to do the same thing.

The failure of For Us the Living notwithstanding, it is hard to overstate the depth of the Museum of Modern Art’s ties to the American government and the strength of its propaganda efforts just before and during World War II. The museum not only developed exhibitions but served as an intellectual and inter-institutional hub. Within its walls, artists met diplomats, anthropologists developed materials for cultural training, and soldiers sought solace for the psychological wounds of combat. At a self-congratulatory gathering in November 1945, museum officials summarized their accomplishments during the war.63 They had provided three kinds of support, they concluded: direct work for the government, the creation and circulation of exhibitions that supported American policies, and the development of an Armed Services Program to support soldiers in the field and after their return home. They had carried out thirty-eight contracts for Nelson Rockefeller’s Office of Inter-American Affairs, for MacLeish’s Library of Congress, and for what came to be the nation’s premier propaganda agency in this period, the Office of War Information. They had brought in more than a million and a half dollars from these contracts alone. They had staged some thirty exhibitions directly connected to the war. They had transformed the exhibitions they created at the Museum of Modern Art into traveling kits and sent these to London, Cairo, Stockholm, Rio de Janeiro, and Mexico City—anywhere, in short, that an alliance needed shoring up. And they had developed a host of programs and tools to help soldiers regain their psychological balance in the wake of combat.

Of all the work they undertook, the museum officials were proudest of a single exhibition, the 1942 propaganda blockbuster Road to Victory. The exhibition “was not only a masterpiece of photographic art but one of the most moving and inspiring exhibitions ever held in the museum,” they wrote.64 Curated by photographer Edward Steichen and designed by Herbert Bayer, Road to Victory borrowed the immersive impulse behind For Us the Living but did so in terms set by Bayer’s extended field of vision. Suddenly the same critics who had found Bayer’s exhibition techniques confusing in 1938 found them to be the epitome of creativity. And the museum officials who had so feared the pseudocinematic power of Leslie Cheek’s design of For Us the Living now embraced a directive, immersive multiscreen environment as a means of bringing visitors to an understanding of America’s wartime mission.

In September 1941, at the same time that Mead and the Committee for National Morale were trying to develop their exhibition on democracy at the Museum of Modern Art, trustee David McAlpin approached photographer Edward Steichen. The museum had begun to host small exhibitions devoted to the fighting in Europe and to American ideals here at home, and McAlpin hoped that Steichen might stage another in the sequence.65 Steichen was sixty-one at the time, with a long career as a gallery owner, portraitist, and advertising photographer behind him. His work showed none of the preoccupations with the extension of the human senses that preoccupied Europeans like Moholy. On the contrary, his images partook of an aestheticized realism. Despite a little soft focus here and a slightly off-center composition there, Steichen’s images were the visual equivalent of American realist fiction: they presented straight-on views of American characters in a largely plainspoken visual idiom.

Steichen accepted McAlpin’s invitation and, in October 1941, began selecting images for the show. He trolled through thousands of photographs, almost all from government collections, and the great majority from the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Across the 1930s the FSA had been the premier chronicler of the Great Depression, but by the end of the decade, hoping to maintain government funding in a changing political climate, the agency’s director asked his photographers to turn away from dark depictions of poverty and toward images and individuals who might provoke a feeling of hopefulness in viewers.66 Of the 150 images that Steichen eventually chose, more than 130 came from the FSA.67 The rest came from the Army and Navy, various press agencies, and several other government bureaus. Like Steichen’s own work at the time, they tended to be “straight” photography—that is, they mostly depicted their subjects in a head-on, straightforward manner, with clear, sharp lines and a strong documentary flavor.

Steichen in turn recruited his brother-in-law, poet Carl Sandburg, to create a text for the show. Like Steichen’s photographs, Sandburg’s poems portrayed the everyday life of Americans in ordinary, seemingly documentary speech. But like Steichen’s pictures, and like the pictures Steichen chose for Road to Victory, Sandburg’s verse elevated its subjects to creatures of myth. In his most famous poem, for instance, Sandburg transformed the notoriously bloody and impoverished stockyards of Chicago into the object of an encomium: Chicago wasn’t a gore-ridden mess; it was the “city of the big shoulders” and “hog butcher for the world.” Finally, in what turned out to be an inspired decision, the Museum of Modern Art’s director of exhibitions, Monroe Wheeler, paired these two middlebrow American realists with a representative of the European avant-garde, Herbert Bayer. The resulting exhibition fused the familiar photorealism of Life magazine with the Gestaltist tactics of Bayer’s extended field of vision—and the utopian ideals of the Bauhaus with the propaganda needs of wartime Americans.

Bayer designed the exhibition as a road, curving through the entire second floor of the Museum of Modern Art and winding by images and texts of varying sizes. When they entered, visitors encountered a floor-to-ceiling photograph of Utah’s Bryce Canyon and huge portraits of three Native American men. The words “Road to Victory” floated over their heads on nearly invisible wires, a look that would have been familiar to El Lissitzky a decade earlier. A text by Carl Sandburg translated the images into words: “In the beginning was virgin land and America was promises—and the buffalo by thousands pawed the Great Plains—and the Red Man gave over to an endless tide of white men in endless numbers. . . .” From there, visitors could meander by vistas of grain waving in wide-open fields, to views of small-town life: a farmer carrying a bushel of corn, a view of grain elevators in Montana, a glimpse of a middle-aged woman out front of her clapboard house. Visitors found the sheer number of such images powerful and their meaning clear. Elizabeth McCausland, reviewing the show for the Springfield Sunday Union and Republican, spoke for many when she wrote, “All these are familiar aspects of American life. . . . This is the stuff of which we build a people and its traditions.”68

FIGURE 3.3.

Entrance to Road to Victory, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1942. Photograph by Albert Fenn. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art, licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York. Used by permission.

Having explored the American nation’s roots in its landscape and the character of its people, visitors then moved on to images of the war itself. As they rounded a curve, they came on a uniquely jarring juxtaposition: a huge photograph of a warship exploding at Pearl Harbor while underneath it, in a separate photograph mounted in a bit of montage, two Japanese government officials laughed above the inscription “Two Faces.” A temporary wall met these images at ninety degrees. On it, an American farmer looked bravely into the distance. Below him, Bayer, Steichen, and Sandburg had written, “War—they asked for it—now, by the living God, they’ll get it.” In fact, Steichen had repurposed a 1938 Dorothea Lange image from the FSA archives, one in which this same farmer, a migrant, had been shown confronting his utter destitution.69 Here, Steichen turned the farmer’s endurance in the face of poverty into visual evidence of American resolve in the face of war.

The exhibition then opened onto scenes of American troops in training, of airmen raining down in parachutes on an unseen enemy, and of bombs doing the same. “Smooth and terrible birds of death,” captioned Sandburg, “smooth they fly, terrible their spit of flame, their hammering cry, ‘Here’s lead in your guts.’” Visitors passed vistas of American warships sailing windblown, choppy seas—in Sandburg’s words, “hunting the enemy, slugging, pounding, blasting. . . .” At last, at the end of the exhibition’s road, visitors confronted an enormous, floor-to-ceiling, panoramic overhead photograph of row upon row of American soldiers marching. These soldiers might well have looked like the anonymous masses of fascist exhibitions from the thirties, had they not featured inset images of middle-aged, white, and mostly rural American couples—clearly meant to be the symbolic parents of the marchers—sitting in front of their houses, on their sofas, and in one case outdoors on what looked like a reviewing stand. Visitors to this final scene were surrounded—by American troops, but also by the same sorts of American citizens they had seen at the start of their journey through the show. If a fascist exhibition asked its viewers to melt into an anonymous mass, this final set of images asked Americans to preserve their individuality, their roots, even as they formed into a fighting machine.

Such an appeal struck a deep chord in audiences. Across the summer of 1942, more than eighty thousand people visited the exhibition.70 Reviewers fell over themselves to praise it. “It would not at all amaze me to see people, even people who have thought themselves very worldly, nonchalant or hard-boiled, leave this exhibition with brimming eyes,” wrote Edward Alden Jewell, the New York Times critic who had disparaged Bayer’s design for the Bauhaus show in 1938.71 Jewell particularly praised the exhibition’s ability to reveal essential aspects of American character and help visitors feel them as their own. If other exhibitions had simply depicted “a nation at war,” this one, wrote Jewell, “reveals the very fiber of the nation itself.” Much like Margaret Mead’s book And Keep Your Powder Dry . . . , the exhibition seemed to Jewell to fuse the nature of the nation with the personality formations of its citizens and to offer that fusion as the source of America’s national might. By drawing visitors down a road, by arraying images above and below eye level, and by mixing images of life at home with life in the Army, Jewell argued that the exhibition drew visitors into a new form of emotional citizenship. “I think no one can see the exhibition without feeling that he is a part of the power of America . . . ,” wrote Jewell. “It is this inescapable sense of identity—the individual spectator identifying himself with the whole—that makes the event so moving.”72

Jewell lacked Bayer’s Gestaltist orientation, but his review proclaimed the success of Bayer’s technique: in Road to Victory, Bayer, Steichen, and Sandburg had created what Moholy might have called a typophoto environment. They offered visitors the chance to experience themselves as individuals in charge of their own movements and, at the same time, to extend the reach of their senses across the American continent and all the way to foreign battlefields by means of the photographs on the walls. They could thus use their eyes to imaginatively stitch themselves into the fabric of the American nation. As once the students of the Bauhaus were to integrate art and technology so as to create a New Man, so here, Road to Victory brought together art and technology to create a new, more confident American.

Of all the reviewers to celebrate this achievement, Elizabeth McCausland explained it most clearly: “The exhibition may be thought of as a movie in three dimensions, with the difference that it is the spectator who moves, not the pictures. In this kinesthetic relation between the one who sees and what is seen lies the explanation of the moving psychological effect of the exhibition. It has visual activity, as life has. It speaks with a variety of accents, and it shows the various faces of remembered experience.” In other words, to enter the physical environment of the exhibition was to enter a place in which one could move back and forth between the external world and one’s internal state of mind, integrating the two. The medium of photography, coupled with the extended field of vision technique, provided evidence with which the visitor could simultaneously reason and feel. At the same time, even though the visual power of the exhibition put McCausland in mind of a film, the exhibition did not seem to manipulate the viewer in the ways that Abby Rockefeller had feared For Us the Living might. As McCausland pointed out, Road to Victory did not “mold” the visitor’s opinions—“for that word smacks of the Fascist concept of dominating men’s minds.”73 Rather, it offered visitors tools and settings with which to remake their own personalities in democratic, pro-American terms.

To appreciate the political valence of Bayer’s design and its impact on visitors like McCausland, we need only look a few blocks uptown, to 57th Street. There, a few months after Road to Victory opened at the Museum of Modern Art, heiress and art collector Peggy Guggenheim opened a multiroom gallery to showcase her collection. Austrian-American designer Friedrich Kiesler divided the space into four themed spaces: the Daylight Gallery, the Abstract Gallery, the Surrealist Gallery, and the Kinetic Gallery. Like Bayer, Kiesler created a pathway through the exhibition. And like Bayer, he hung images at unusual levels. He configured the Surrealist Gallery like a tunnel, for example, with curved walls and unframed paintings jutting outward on struts to within a few inches of viewers. The Abstract Gallery, too, featured wraparound walls, this time made of cloth; its paintings hung from wires strung floor-to-ceiling in the middle of the room.

Like Bayer, Kiesler was trying to reinvent the traditional relationship between viewers, art, and the spaces in which they encountered one another. But Kiesler was working within a radically different psychological framework. In a press release for the show, he explained that his display technique offered “a much better possibility for concentrating the attention of the spectator on each painting and therefore a better chance for the painting to communicate its message.”74 For Kiesler, the psychological impact of the viewers’ movements through the exhibition space depended primarily on their encounters with individual images rather than with the pattern of their arrangement. In his view, pictures contained messages and, when properly attended to, they could transmit them. “Man,” wrote Kiesler at the time, “seeing in a piece of sculpture or a painting on canvas the artist’s projected vision, must recognize his act of seeing—of ‘receiving’—as a participation in the creative process no less essential and direct than the artist’s own.”75 For Kiesler, the creative process was an act of communication initiated by the artist, enacted by the individual work of art, and completed by the viewer’s passive reception of the message carried by the work. The role of the display was to facilitate this sequence.

Critics were quick—and largely dismayed—to catch Kiesler’s drift. “To the uninitiated and unenlightened,” wrote one, “most of the paintings look like pieces of canvas on which artists have wiped their brushes while the sculptured works of the chiselers look like they are a long way from being finished. The devotees of surrealism, however, insist that these works of art have real meaning if you know how to get it.”76 One writer after another echoed this view: in Kiesler’s galleries, art works needed to speak to viewers; viewers needed to hear and “get” their messages; the environment itself had been designed to make it easier for viewers to passively receive the aggressive intellectual and aesthetic challenges posed by the art. Such a structure did little to promote the sort of democratic agency offered by Bayer and Steichen’s Road to Victory. On the contrary, wrote Henry McBride of the New York Sun, “this scheme [of display] is too much like the ‘ordered society’ of the Japanese. It compels you to have the correct thought at the correct time. It is not my idea of aesthetic liberty.”77

McBride penned these lines less than a year after Pearl Harbor. The fact that he did suggests both the intensity of his reaction to Kiesler’s work and the political stakes of exhibition design in this period. Art of this Century remained controversial until it finally shut down in 1947. By contrast, Road to Victory was so popular that Monroe Wheeler and the Office of War Information teamed up with Bayer the next year to create a sequel, Airways to Peace. Though it did not have the public impact that Road to Victory did, Airways to Peace presented a powerful, even utopian vision of a postwar world, and a glimpse of the role that Bayer’s extended field of vision would play in it. By June of 1943, when the exhibition opened, the tide of the war had begun to turn. British forces had pushed the Germans out of North Africa, American troops had begun working their way up the Solomon Islands toward Japan, and the Soviets had captured some ninety thousand German troops at Stalingrad. American intellectuals, journalists and government officials had begun to turn toward imagining a new international order—one in which a victorious America would play a leading role. They had also begun to see how the massive industrial shifts demanded by the war might become resources in peacetime. In 1943, reporters were particularly fascinated with air power: less than fifty years earlier, no one had flown; by 1943, military and commercial airplanes had traveled around the globe.

In 1942, former presidential candidate Wendell Willkie proved the point. That August he set out in a four-engine bomber piloted by an Army crew on a forty-nine-day trip around the world. The plane visited every continent save Australia, and Willkie himself used the occasion to visit military commanders and politicians in the Middle East, Russia, and China. His book-length chronicle of the trip, One World, became an instant bestseller. Within five months of its March 1943 release, the book had gone through ten printings and sold more than 1,200,000 copies.78 At one level the book was simply a wartime travelogue. “America is like a beleaguered city that lives within high walls through which there passes only an occasional courier to tell us what is happening outside,” wrote Willkie. “I have been outside those walls.”79

At another level, though, the book articulated a utopian vision of a postwar world, abroad and at home. The same technologies that allowed him to travel and that were winning the war for America, Willkie argued, had transformed the globe into a single community. This fact presented Americans with the chance to pursue three possible routes after the war: a parochial nationalism, an international imperialism, or “the creation of a world in which there shall be an equality of opportunity for every race and every nation.”80 Willkie argued that Americans had to begin planning immediately, with the aid of the then-new United Nations, to build—and lead—this postwar world. At the same time, he argued, they must eliminate racism at home. “Minorities are the rich assets of democracy,” he explained. “We cannot fight the forces and ideas of imperialism abroad and maintain any form of imperialism at home. The war has done this to our thinking.”81 Americans instead had to create a new social unity, one in which individuals might preserve their unique personalities and cultures and yet belong to the whole.

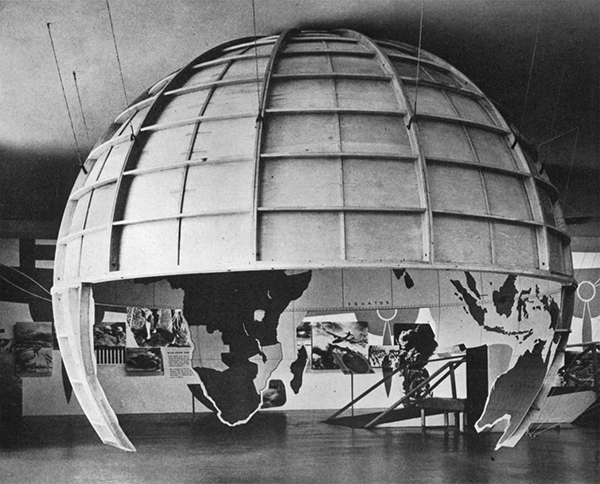

In the summer of 1943, just as Willkie’s book was topping the bestseller lists, Wheeler and Bayer created a visual environment in which visitors could integrate Willkie’s vision into their own views of the world. Like Road to Victory, Airways to Peace featured a broad path for visitors to follow and an array of images and texts—this time written by Willkie—at every level of vision through which the visitor walked. Upon entering the show, visitors confronted a floor-to-ceiling photocollage depicting an airplane flying through the clouds, its wings linked to a drawing of Icarus, beside a long introduction by Willkie. The airplane, he wrote, soared over natural landscapes and cities alike, uniting the organic and the man-made. “There are no distant places any longer: the world is small and the world is one,” it explained. “The American people must grasp these new realities if they are to play their essential part in winning the war and building a world of peace and freedom.”82

As visitors left Icarus behind, Bayer’s design offered them repeated opportunities to imagine themselves flying above the earth. They first encountered some thirty globes and maps, including a clay tablet map from 2500 BCE, a globe from 1492, and Franklin Roosevelt’s own Oval Office globe, which he lent to the museum for two weeks.83 In keeping with the principles of his extended field of vision, Bayer surrounded visitors with visual elements, but in a manner designed to produce a limited range of conclusions. Here he offered visitors the chance to link the global expansion of America’s military presence and its pursuit of victory to the expansion of the human race as a whole. The American project was a human project; what was good for the state was good for humankind. As a contrast, the exhibition presented “Mackinder’s Famous Map,” which depicted “Eurasia” at its center. The exhibitors argued that this map depicted the globe as the Nazis saw it—with North America at its outer edge—but not as it actually was. Seeing the world correctly, they implied—that is, seeing the world with America at its center—offered the key to American victory and world peace.