Photo Section

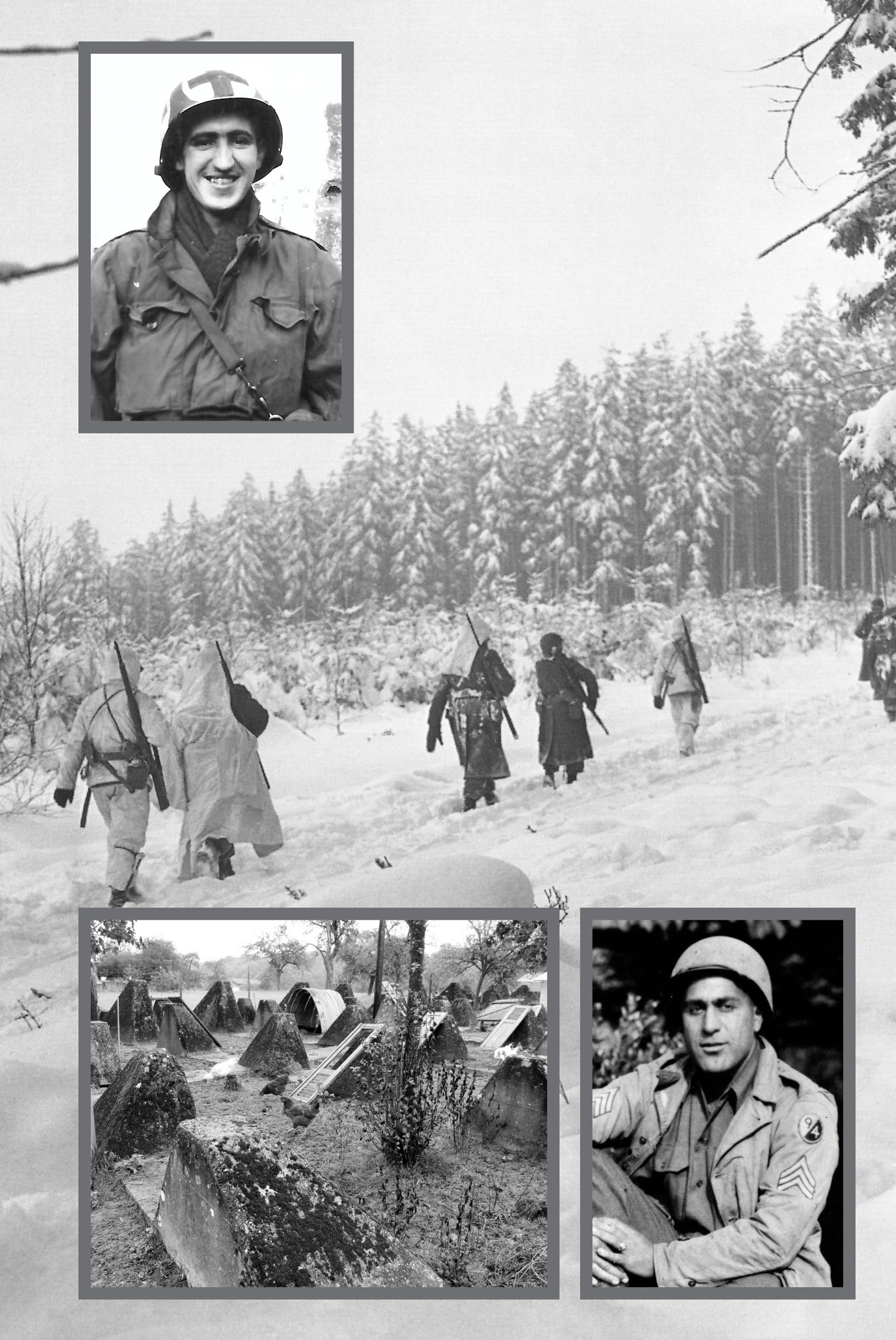

During the Battle of the Bulge, in 1945, these wooded areas just inside Germany hid a network of anti-personnel weapons—land mines, booby traps, and dragon’s teeth (BOTTOM LEFT). When US infantrymen triggered them, it was up to medical corpsmen to bring out the wounded. Medic Alex Barris (TOP LEFT) directed stretcher-bearers with wounded to an aid station, and from there medic Tony Mellaci (BOTTOM RIGHT) arranged for motor ambulance transport. Both served in the 319th Medical Battalion with the US 94th Infantry Division.

Winter fighting background, dragon’s teeth, and Alex Barris in Red Cross helmet: author’s collection; Tony Mellaci at Nantes: courtesy of Tony Mellaci.

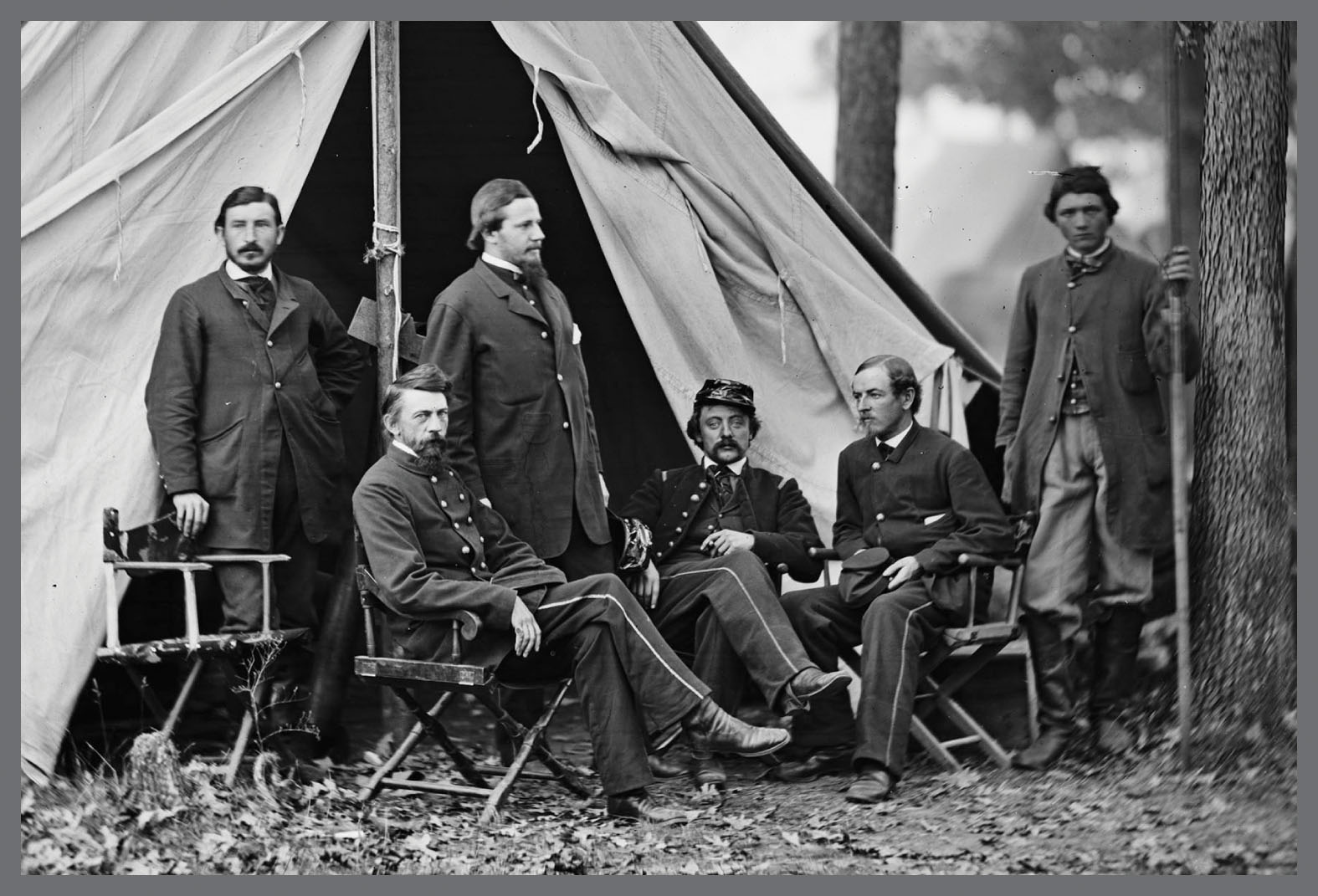

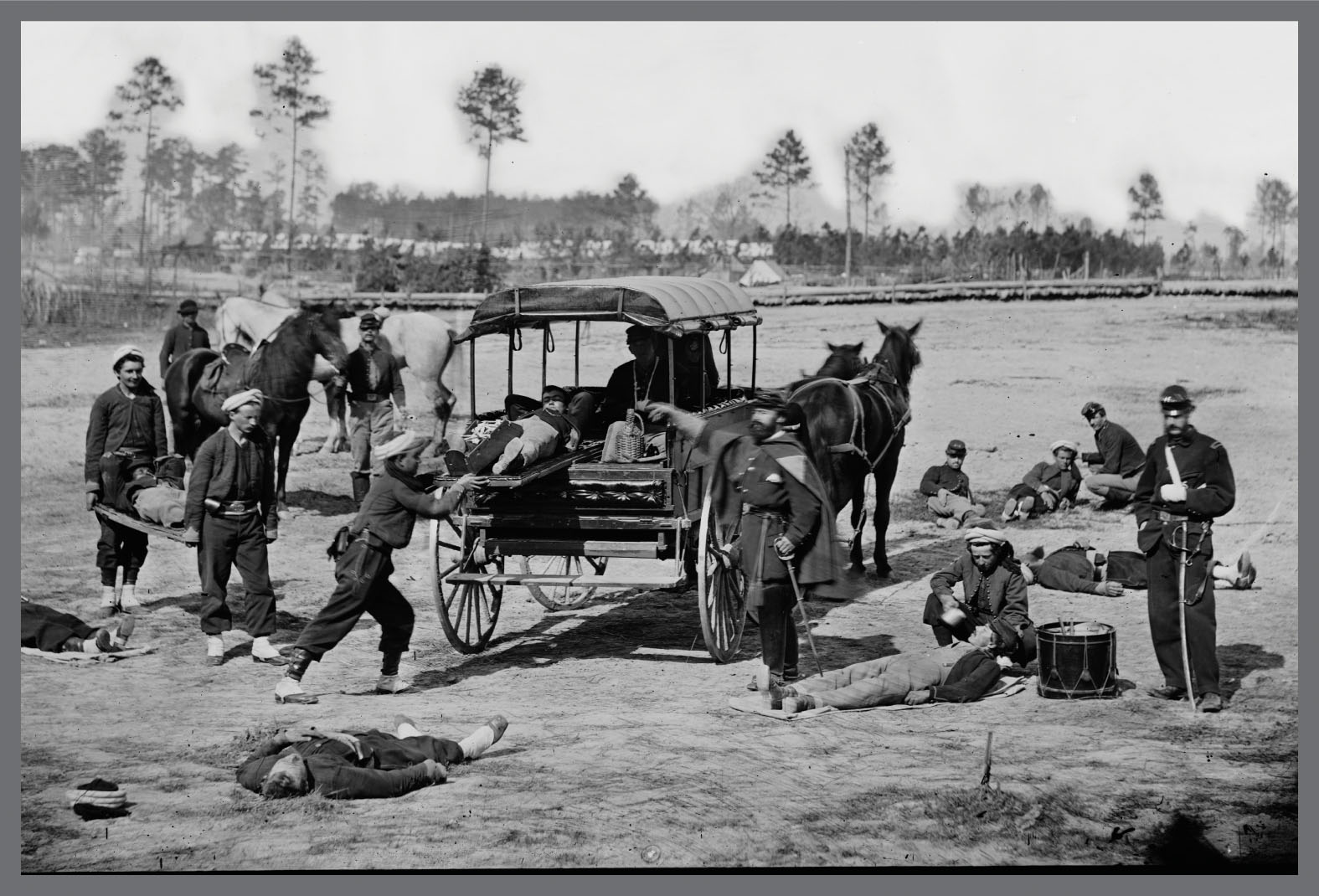

In the US Civil War, as many as 750,000 combatants died. As an example, casualties in the Battle of Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg, Virginia, on December 13, 1862, were typical—nearly 13,000 Federal soldiers killed or wounded in one day’s fighting. It might have been worse on the Union side if not for the introduction of the field ambulance (ABOVE) and a well-organized support system of ambulance trains to retrieve, triage, and treat the wounded. The concept was introduced at Fredericksburg by Jonathan Letterman (TOP, SEATED IN FRONT), medical director of the Union Army of the Potomac. He was later described as “the father of battlefield medicine.”

Jonathan Letterman at US Civil War military camp and field ambulance: Library of Congress, National Archives Still Picture Unit.

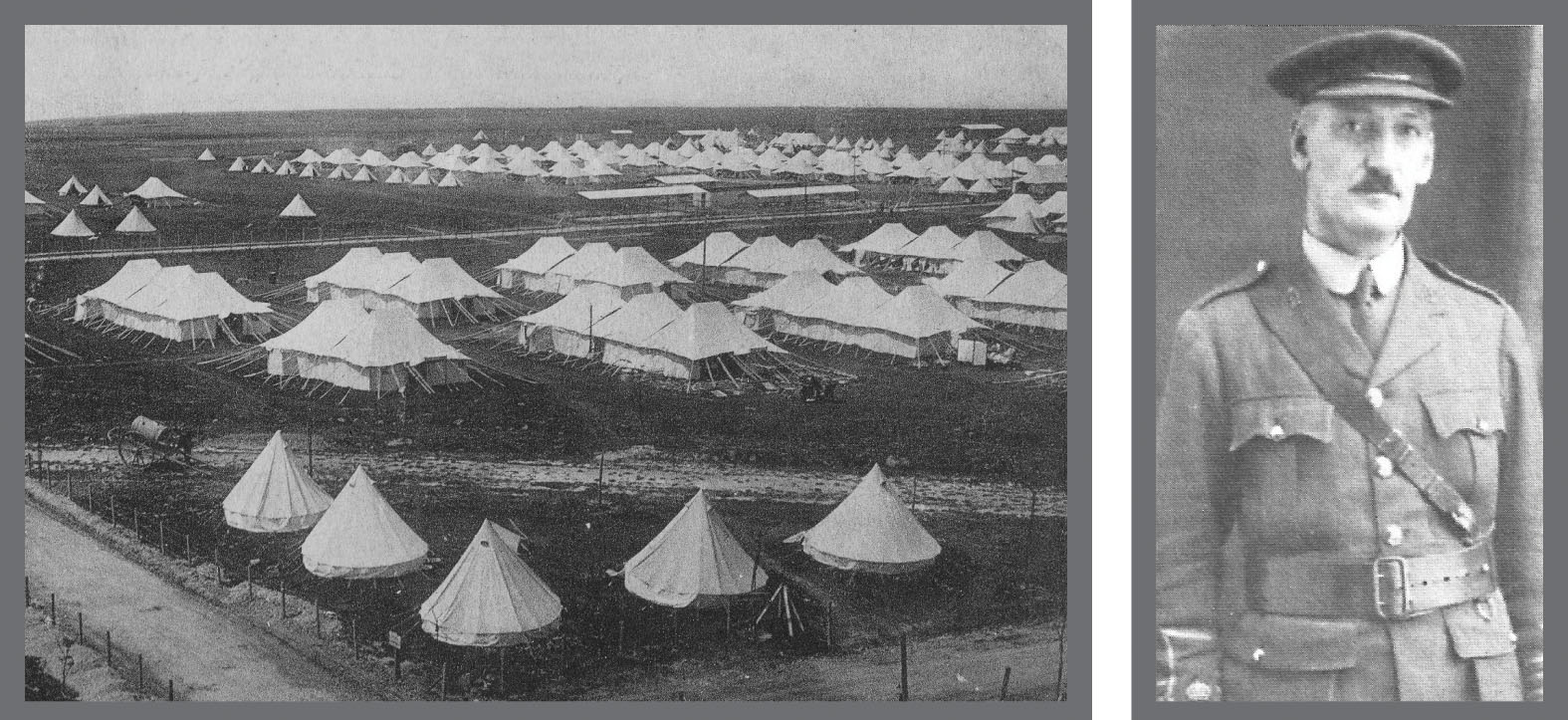

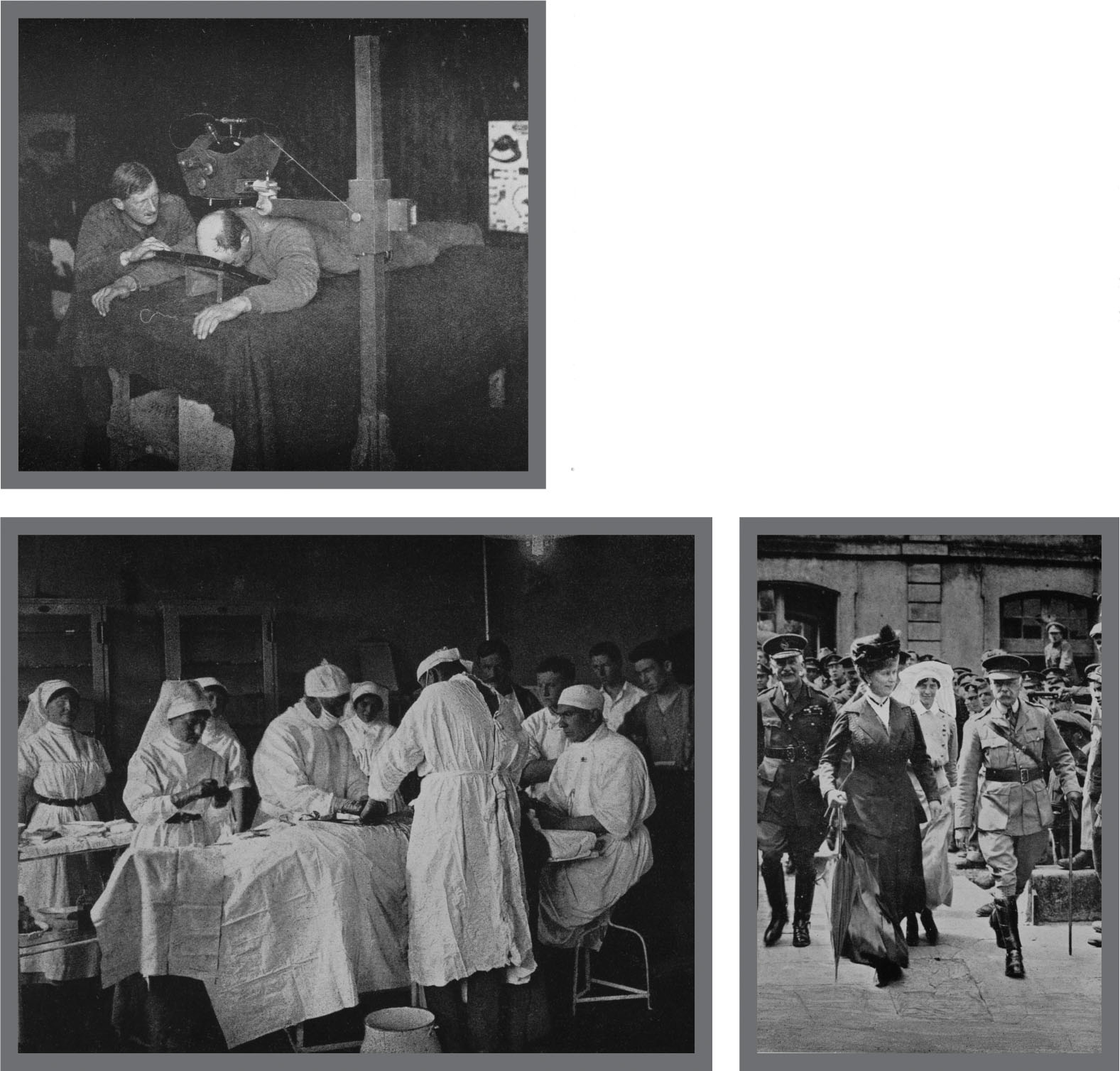

To help treat the steady flow of wounded from the Western Front in early 1915, McGill University as well as the Montreal General and Royal Victoria Hospitals transported 1,700 volunteer students, doctors, and nurses to France. Housed in tents (TOP LEFT) on open terrain along the French coast, No. 3 Canadian General Hospital (CGH) would initially provide 315 volunteer staff to support 1,040 beds tending the wounded.

The facility at Dannes-Camiers, in France, included an admission tent, diagnosis tables, registration facilities, an x-ray machine (LEFT), operating theatres, recovery areas, and recreation huts. Among No. 3’s most experienced surgeons was Edward Archibald (TOP RIGHT AND BOTTOM LEFT, FOURTH FROM LEFT), known for his work “shrapnel hunting” in body and head wounds. As well as daily convoys of wounded, No. 3 CGH welcomed Minister of Militia Sam Hughes, creator of the Canadian War Records Office Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook), and Queen Mary (BOTTOM RIGHT) on July 3, 1917.

Canadian General Hospital in tents in France: courtesy of Florence Watkinson and the Port Dover Harbour Museum; Edward Archibald, No. 3 Canadian General Hospital x-ray unit, operating theatre, and Queen Mary’s visit: Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University.

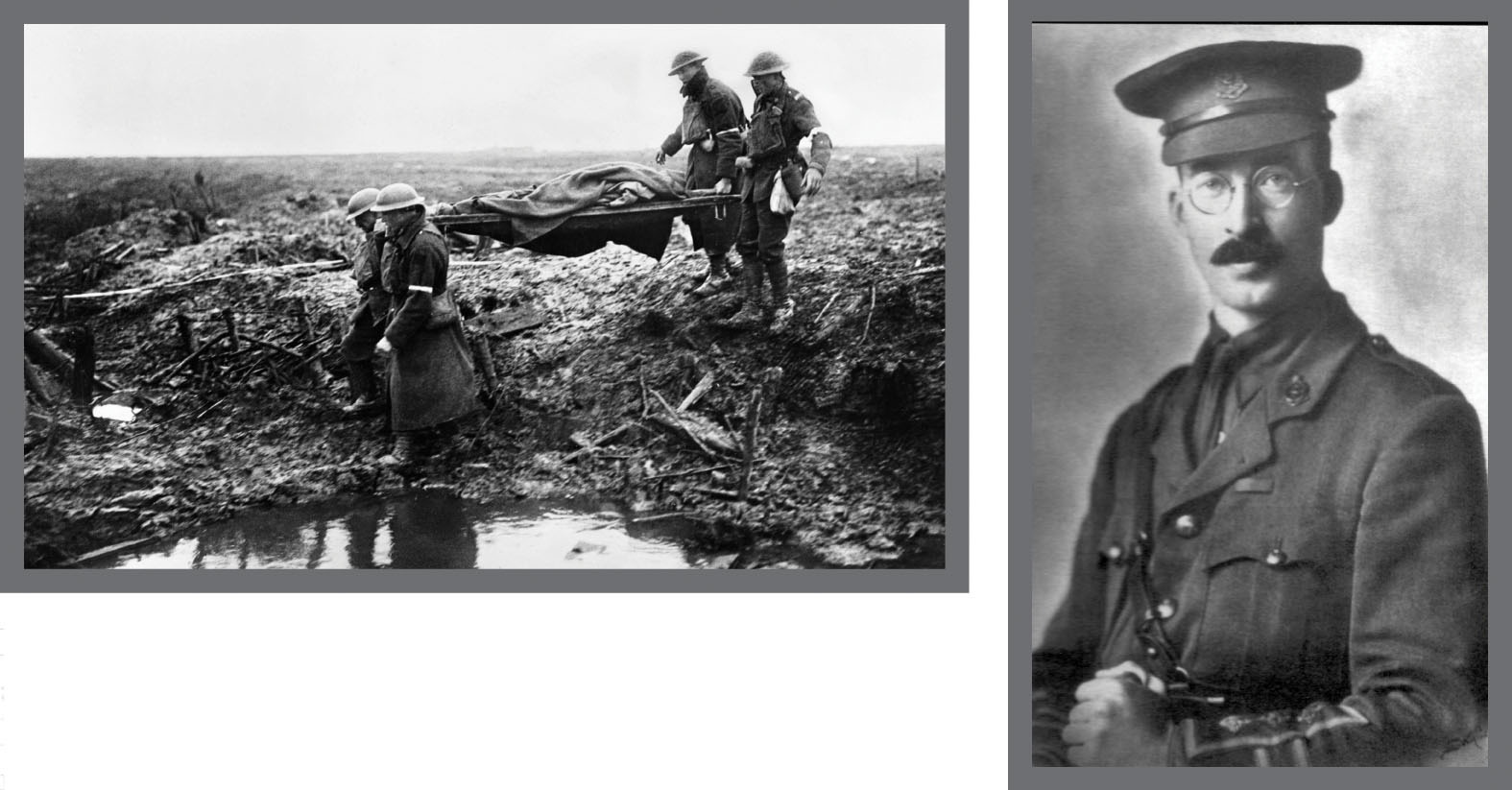

In April 1915, medical officer Francis Scrimger (RIGHT) evacuated forty wounded from the appropriately named “Shell Trap Farm” advanced dressing station in Belgium, shielding one man with his own body; he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

On April 22 and 23, 1915, German troops advanced behind a wall of chlorine gas (ABOVE RIGHT) against Allied trenches near Ypres, Belgium. Cluny Macpherson (LEFT), a medic from Newfoundland, then faced the task of finding a defence against the toxic weapon.

Remembering headgear he had employed to protect patients in transit from the cold in Labrador, Macpherson created a prototype helmet (ABOVE) combining a Viyella cloth hood, a breathing hole, and a visor made of nonflammable film; then he marshalled workers in the UK to manufacture a million gas masks before the Germans launched yet another gas attack. Not seeking fame or fortune, Macpherson gave his invention “freely in the cause of humanity.”

First World War stretcher-bearers: courtesy of Glenn Warner and Glenn Kerr (Central Ontario Branch of the Western Front Association) and Library and Archives Canada, William Rider-Rider Collection, O-2202; Francis Scrimger: Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University; April 22, 1915, German gas attack: courtesy of Glenn Warner and Glenn Kerr (Central Ontario Branch of the Western Front Association) and Canadian War Museum, George Metcalf Collection, 19700140-077; Cluny Macpherson and soldiers in gas masks: Faculty of Medicine Founders’ Archive, Health Sciences Library, Memorial University.

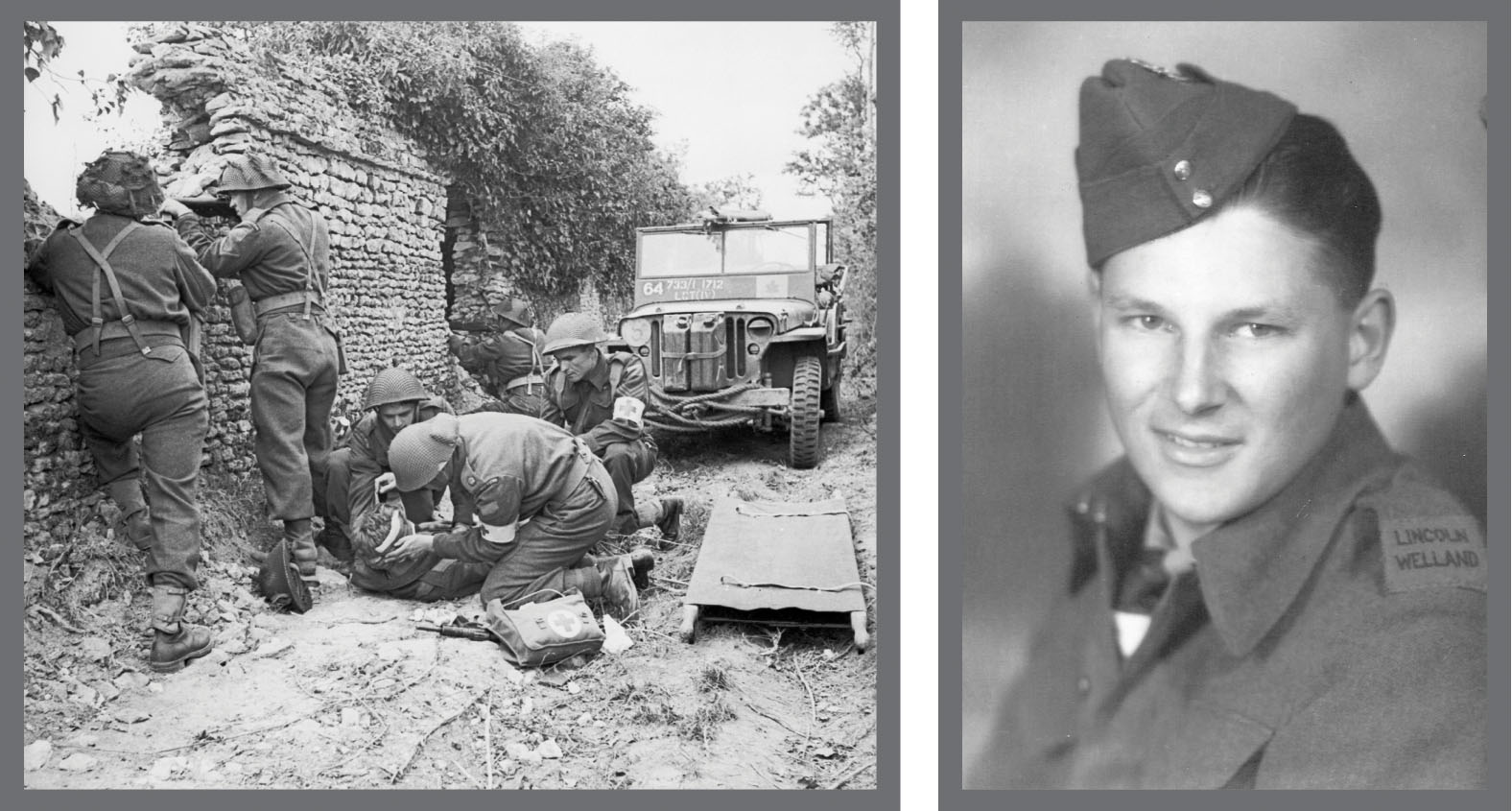

During the Dieppe raid in August 1942, medical officer Laurence Alexander (TOP RIGHT) attempted in vain to get ashore to attend Canadian wounded there; aboard a burning landing craft (ABOVE), he dealt with dozens of casualties and listened to “a constant tattoo” of enemy machine-gun bullets pounding the vessel. Meanwhile, on the beach, medical officer Wesley Clare (TOP LEFT) faced the reality that eighty to a hundred wounded men huddled in the lee of a landing craft would have to surrender or drown in the rising tide. They would spend the rest of the war in German POW camps.

In Normandy during the invasion (ABOVE LEFT), medics coped with casualties alongside infantry firing on enemy positions. At Hill 195 in August 1944, medic Jim Brittain (ABOVE RIGHT), with the Lincoln and Welland Regiment, wasn’t sure which was hotter that summer: the blistering sun or the continuous fire from German mortars, machine guns, and 88 mm artillery.

Wesley Clare: courtesy of Scott Clare; Laurence Alexander and Dieppe battle scene: courtesy of Rob Alexander; Members of the Regimental Aid Party of the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN no. 3206448; Jim Brittain: courtesy of Ron Brittain.

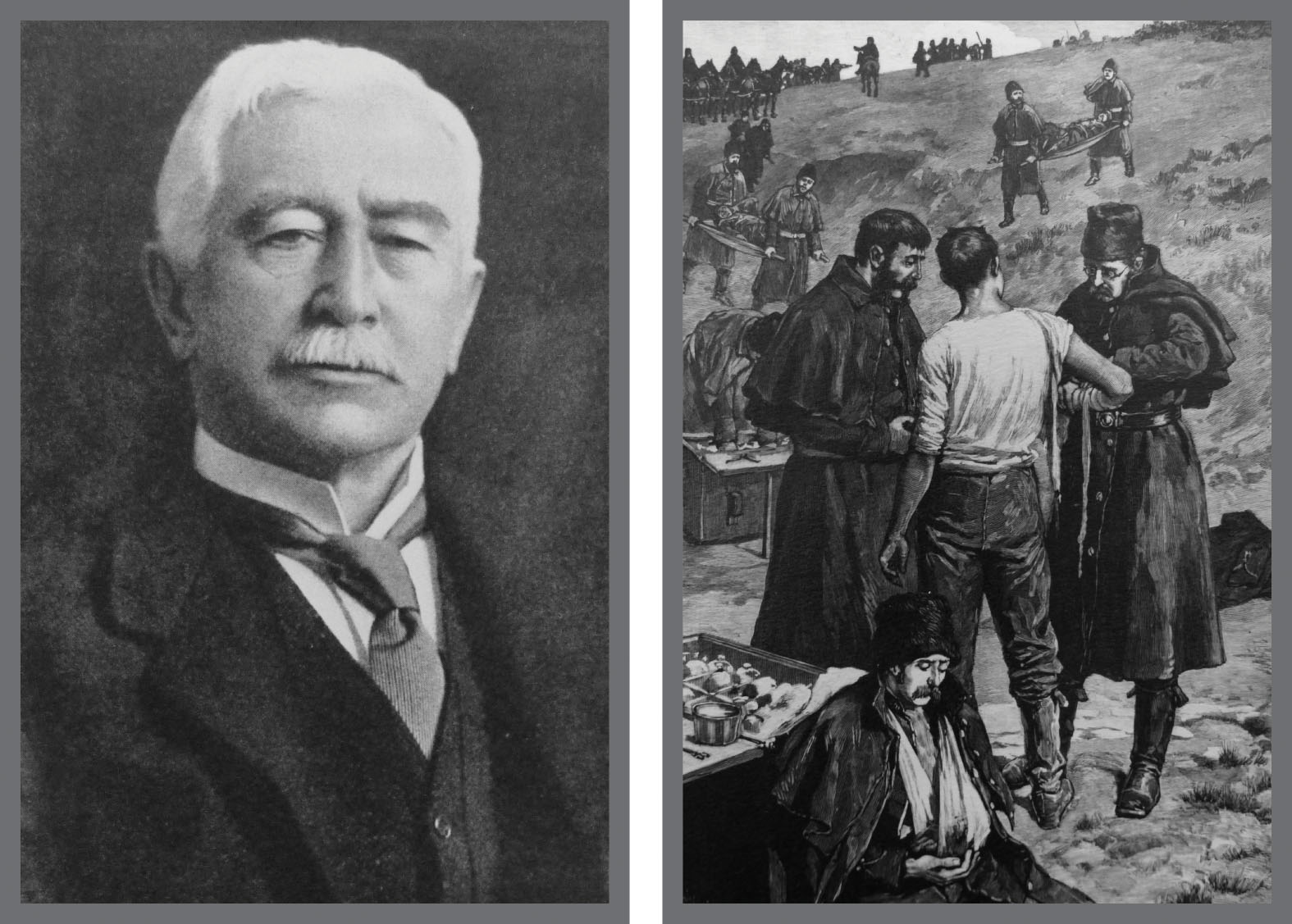

During the 1885 Riel Uprising, urban surgeon Thomas Roddick (TOP LEFT) had to adapt to conditions of a frontier battlefield in western Canada. Under canvas and out in the open near Batoche (TOP RIGHT), his medical corps conducted fifty-three surgeries, extricating bullets and treating fractures while keeping germs at bay.

Alannah Gilmore (ABOVE) brought all the medic skills her deployment to Afghanistan in 2007 demanded; just as often, the crew commander of a Canadian Army Bison ambulance also relied on her trained “muscle memory” in emergencies and a keen sense of “situational awareness” to anticipate the unexpected.

Thomas Roddick and Batoche medical scene: courtesy of Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University; Alannah Gilmore in Bison ambulance: courtesy of Alannah Gilmore.

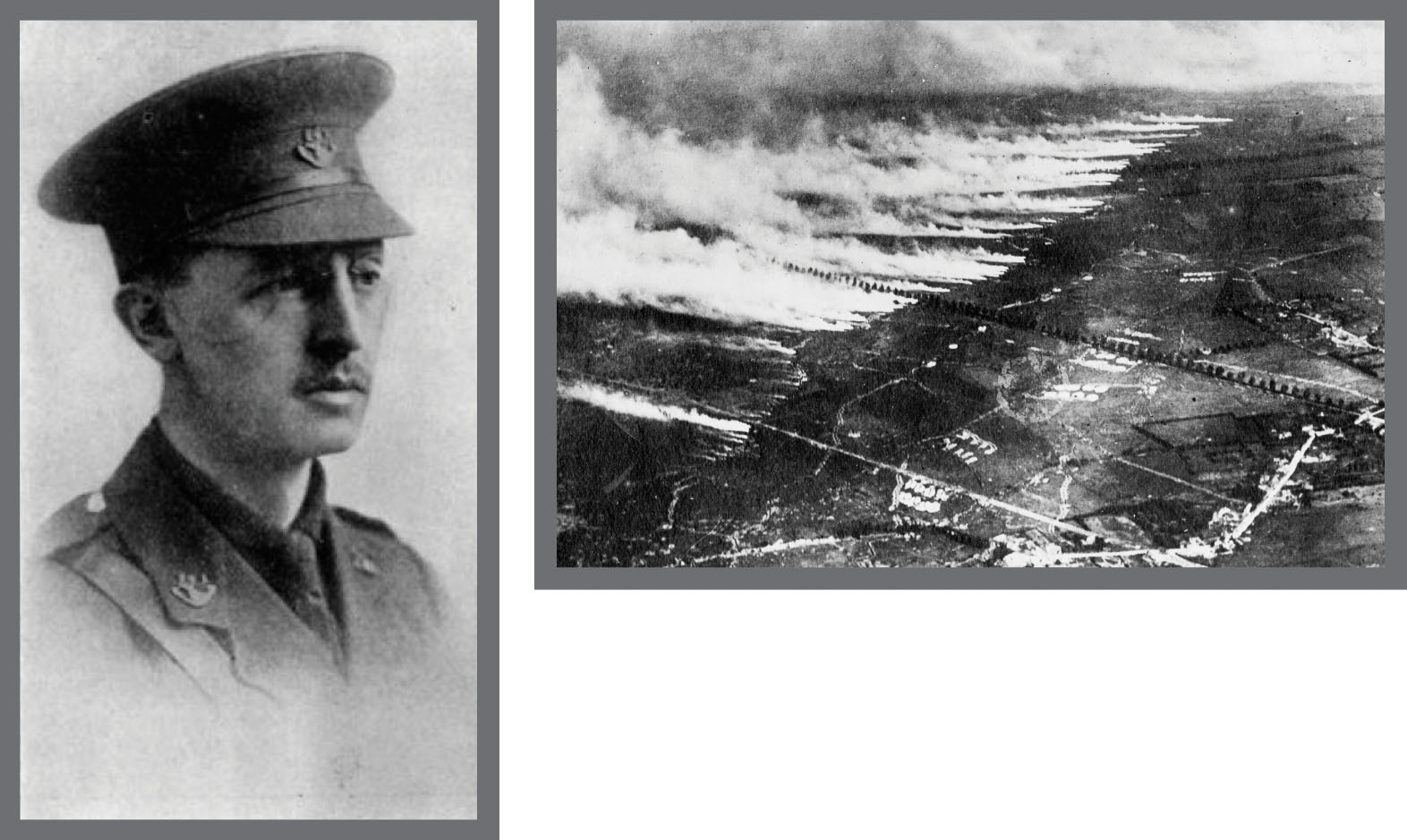

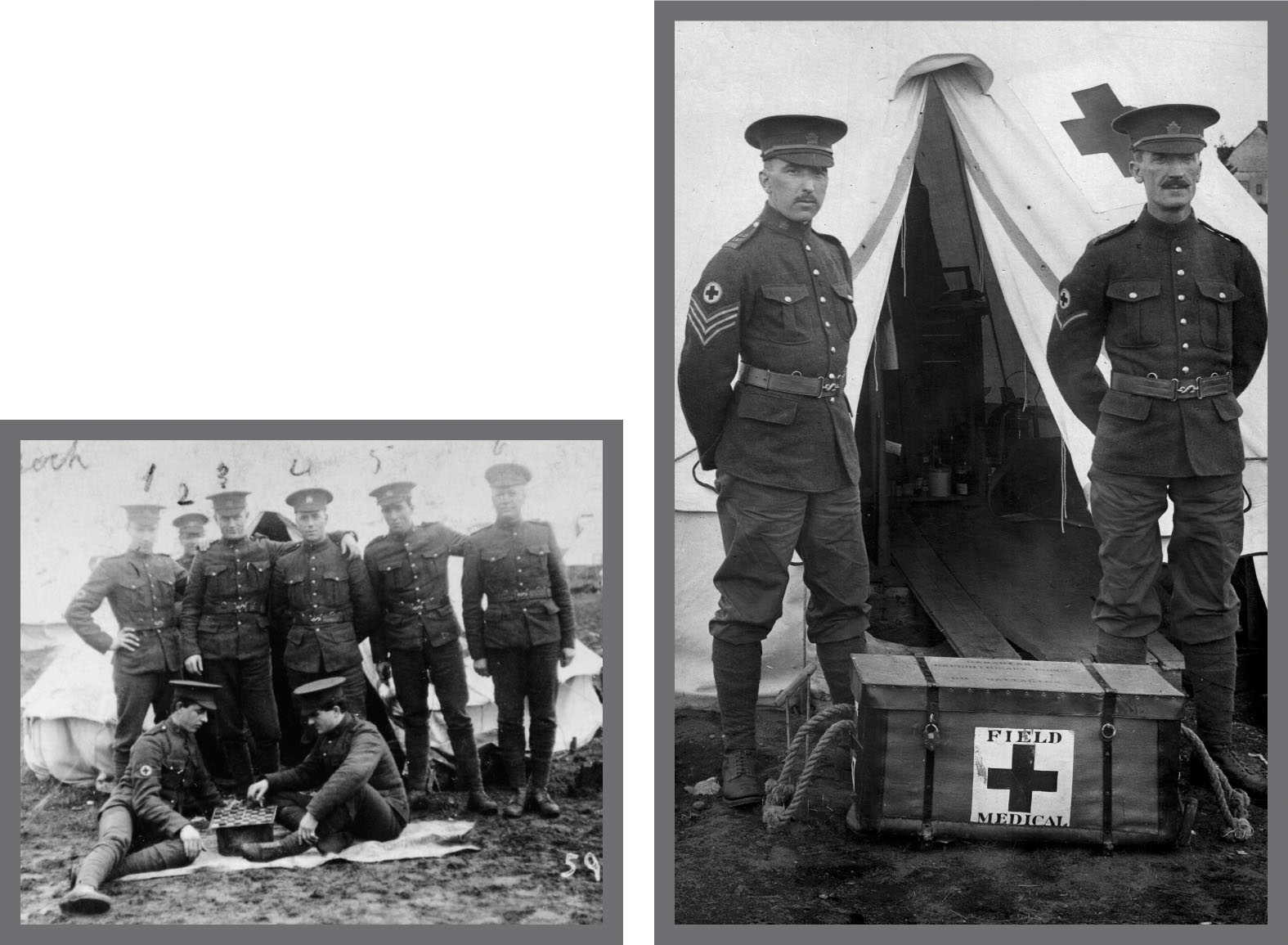

In 1916, rather than take a posting to train field ambulance recruits in England, Montreal volunteer John Kennedy (TOP RIGHT, ON LEFT) took a pay cut—from $1.50 a day as a sergeant to $1.10 a day as a private—to join No. 9 Field Ambulance in the Canadian Corps on the Western Front. He helped boost the morale of stretcher-bearers by getting their commanders to find qualified cooks to provide better food for ambulance crews.

Characteristic of British Empire enlistees, Frank Walker (ABOVE LEFT, STANDING AT LEFT END) served on the Western Front with No. 1 Canadian Field Ambulance among volunteers who came from the same town or province, in his case Prince Edward Island. Field ambulance crews in the Great War had a casualty rate of 8 percent and a fatality rate of 4 percent. While more distant from the front lines, ambulance drivers such as Grace MacPherson (ABOVE), with the Voluntary Aid Detachment of the British Red Cross, delivered wounded to military hospitals on the coast of France, where they became targets of German bombers in the spring of 1918.

John Kennedy and fellow medic of No. 9 Field Ambulance: courtesy of Lisa Boyce; Frank Walker and fellow medics of No. 1 Field Ambulance: courtesy of Mary Gaudet; Grace MacPherson and her VAD ambulance: Canadian War Museum AN-19920085-357.

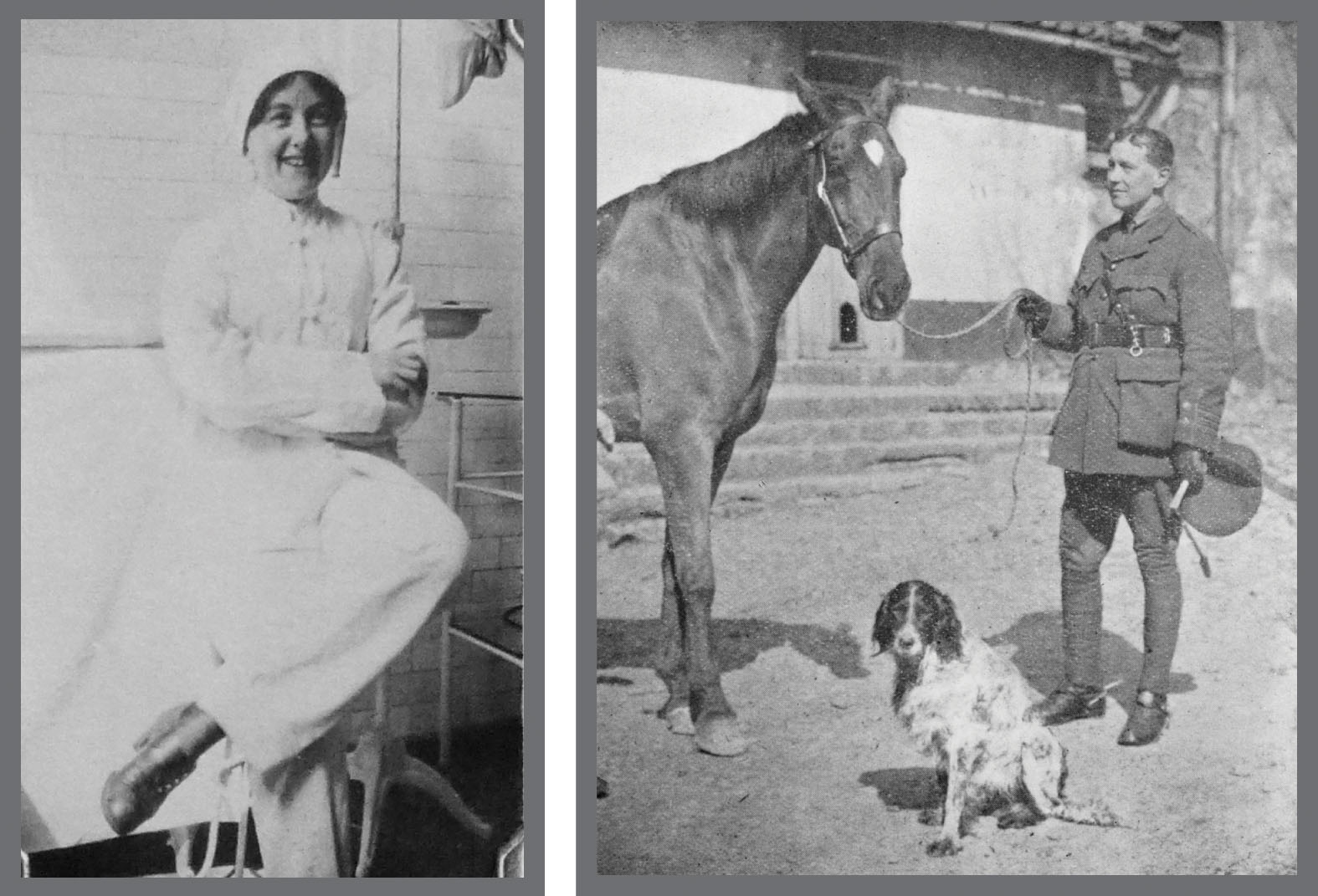

Medical staff in the Great War understood the risks of service close to the front. Field surgeon John McCrae (TOP RIGHT), shown with his horse Bonfire and dog Bonneau, operated on patients well within range of enemy machine guns and artillery. Working at military hospitals along the coast of France, forty miles behind the lines, offered Katherine Maud Macdonald (TOP LEFT) some sense of security . . . until May 19, 1918. During two hours of airborne attacks that night, German aircraft dropped 116 bombs on Allied hospitals; Macdonald, two other nursing sisters, and eight patients died of their wounds. Damage, as at No. 7 Canadian General Hospital (ABOVE), was extensive. Of 3,141 women serving in the Canadian Army Medical Corps in the Great War, forty-six died of enemy action or disease while on duty.

Katherine Maud Macdonald and John McCrae with Bonfire and Bonneau: Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University; No. 7 Canadian General Hospital after May 19, 1918, bombing: courtesy of Florence Watkinson and the Port Dover Harbour Museum.

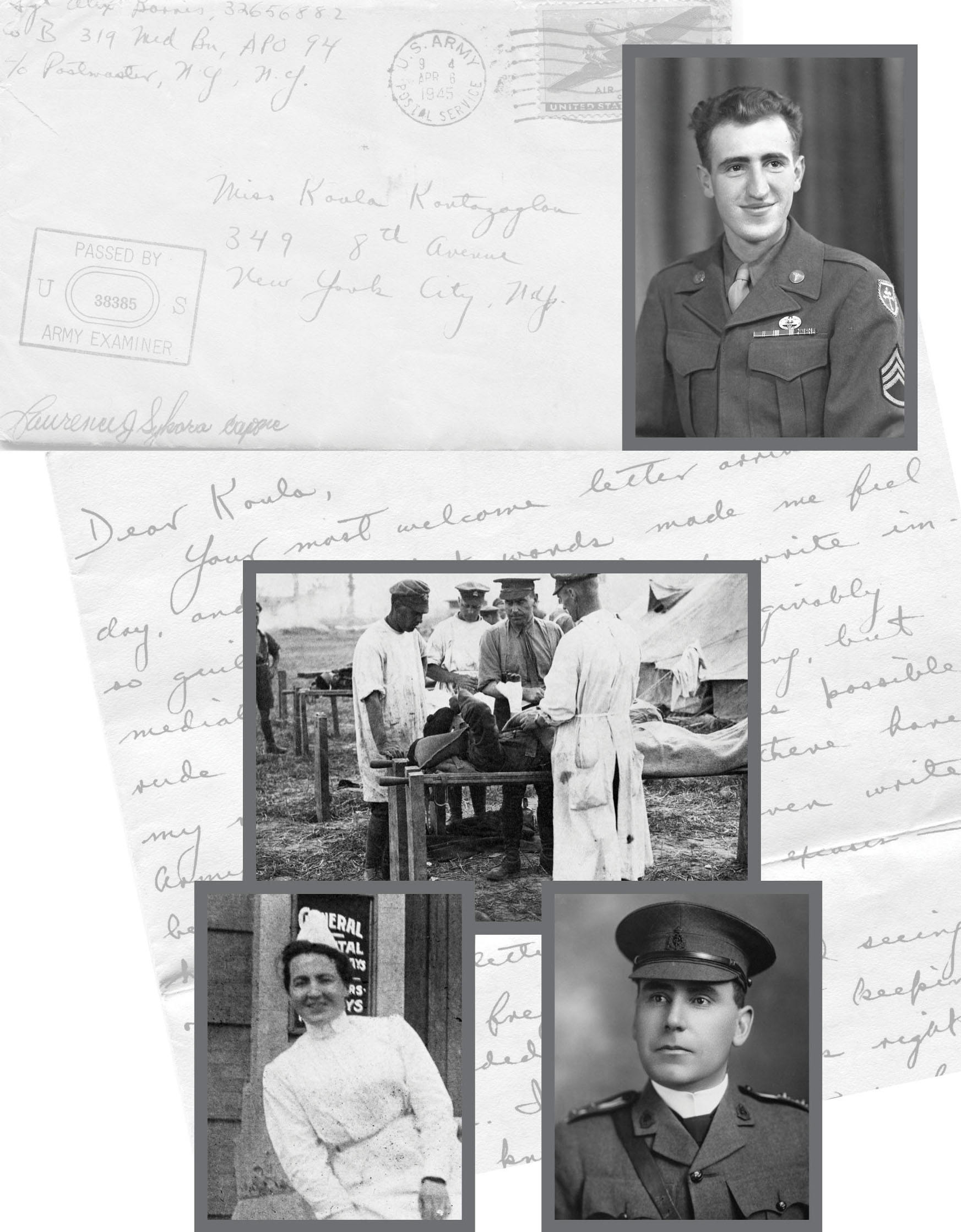

Relationships spawned by circumstances of war: In 1945, army medic Alex Barris (TOP RIGHT) composed this letter to his school-chum-turned-confidante Koula; he offered insights, shared secrets, and hoped they could one day get back together. In contrast, medical officer Harold McGill (MIDDLE, IN DARK UNIFORM, AND BOTTOM RIGHT) corresponded regularly throughout the Great War with Nursing Sister Emma Griffis (BOTTOM LEFT); eventually that connection by mail blossomed into a commitment of love, marriage, and a return to civilian life together.

Envelope and letter background and Alex Barris photo: author’s collection; Harold McGill at dressing station (NA-4938-17), Emma Griffis outside Calgary Hospital (NA-4938-10), Harold W. McGill portrait (NA4938-16): all Glenbow Alberta Institute Archives.

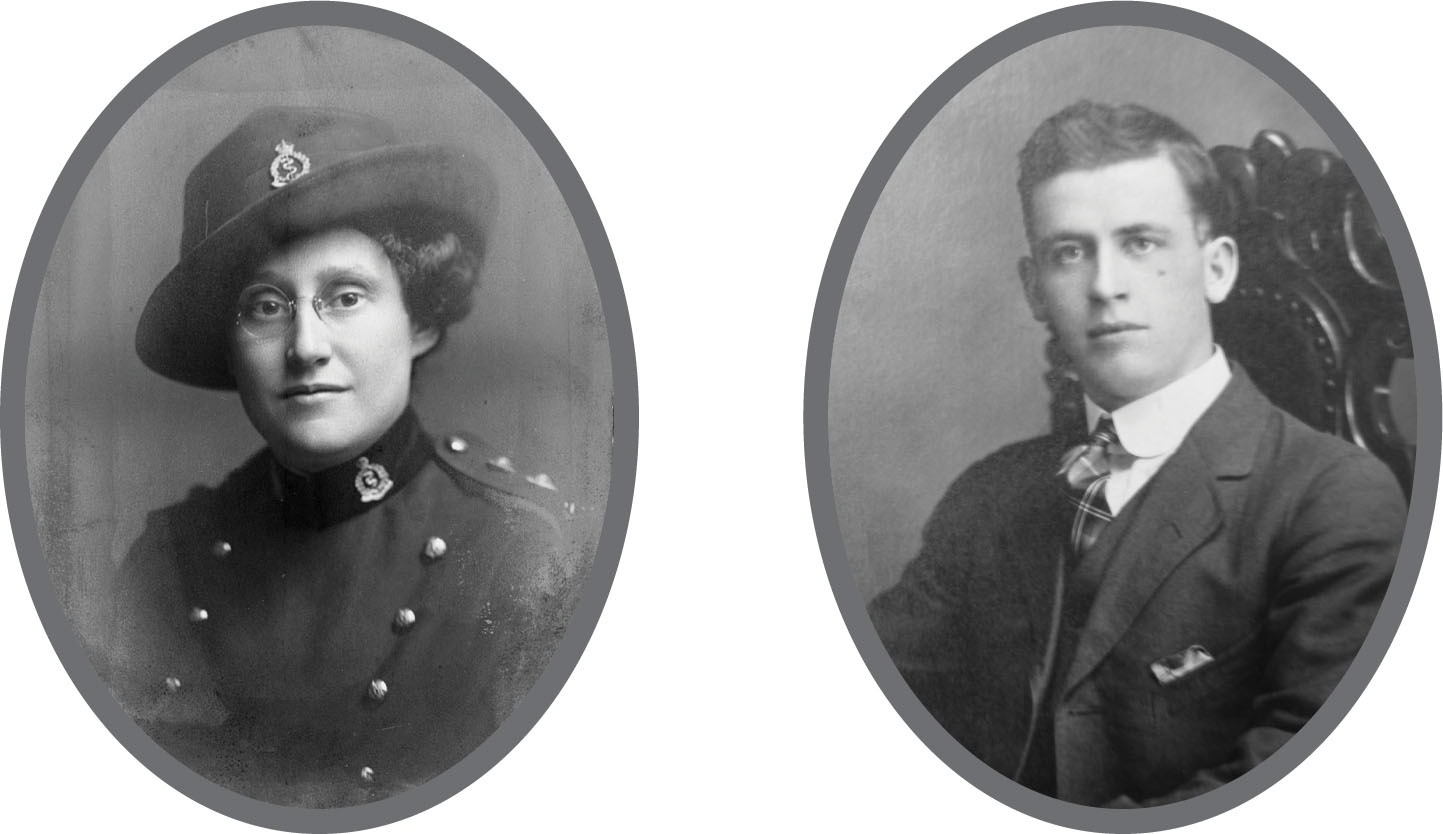

Regulations at the UK military hospital where they served in the Canadian Army Medical Corps restricted staff cook Fred Lailey (TOP RIGHT) from fraternizing with Nursing Sister Louise Spry (TOP LEFT). As Fred put it, he was told, “Look but don’t touch.” But the couple proved that love has a way, and secretly married just outside London on June 18, 1918.

When the 8th Princess Louise’s (New Brunswick) Hussars found a foal (ABOVE) wounded in the crossfire of a battlefield near Coriano, Italy, their regimental medics attended her shrapnel wounds with salves and a belly bandage. It was the beginning of a unique relationship; christened “Princess Louise,” the horse mascot travelled with the Hussars all the way to VE-Day and home to Canada.

At Christmas in 1944 in Bastogne, Belgium, American medical officer Jack Prior (TOP) and Congolese-born nurse Augusta Chiwy (ABOVE) were thrown together as the Battle of the Bulge raged around them; their struggle to save lives and to survive themselves brought this unlikely pair of heroes together in a nearly doomed city.

Louise Ann Spry: courtesy of Donna Henderson and City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 234, Series 1200, Subseries 3, File 1; Frederick Charles Lailey: courtesy of Donna Henderson and City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 556, File 13; Princess Louise horse mascot: courtesy of Harold Skaarup, Tom McLaughlan, and Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN no. 3240626; Jack Prior and Augusta Chiwy: courtesy of Martin King.

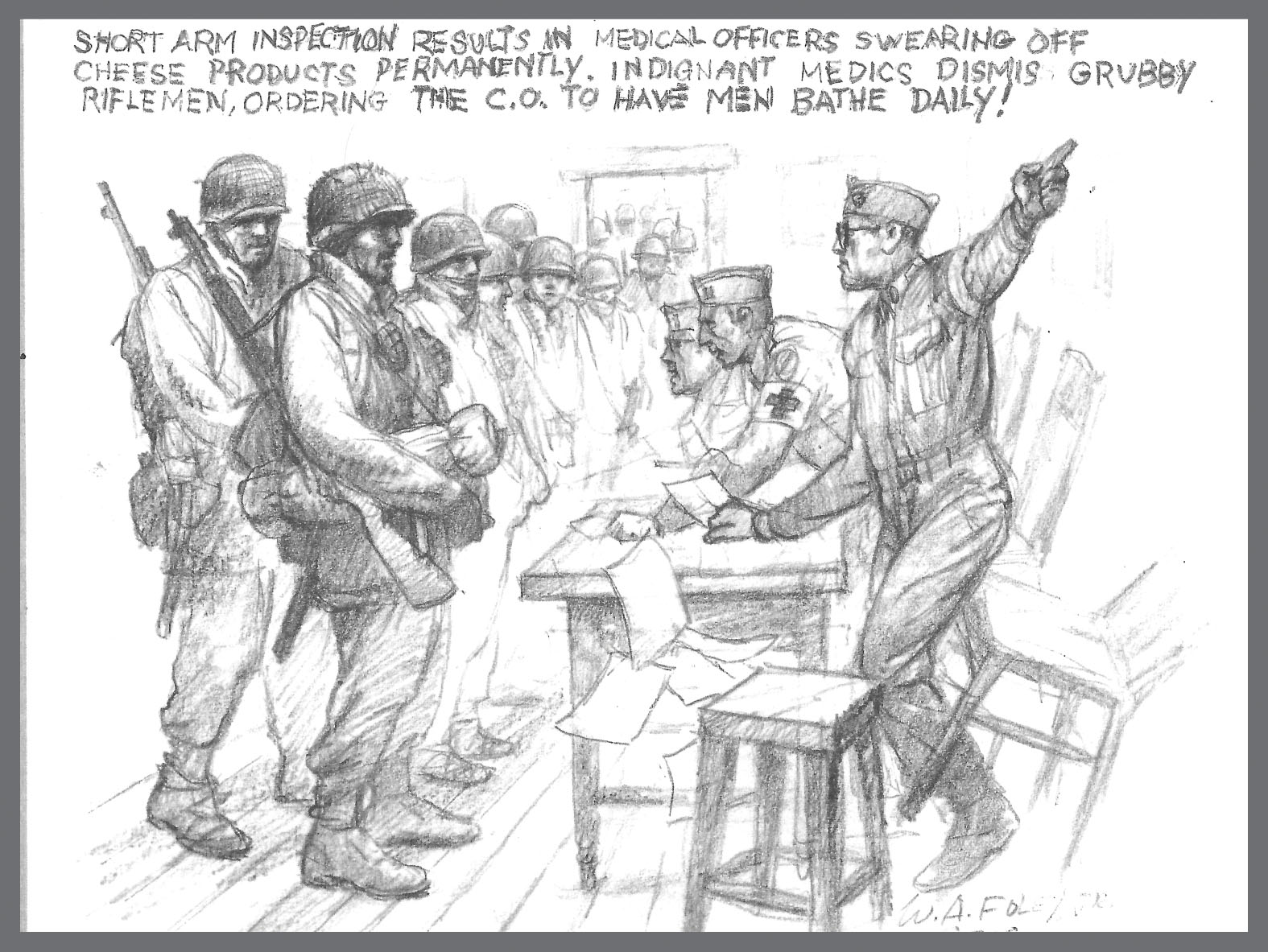

The credo that civilian-cum-US-Army-doctor Raiden Dellinger (TOP LEFT, on RIGHT) practised in 1944–45 overseas included life-saving surgery on comrades just behind the front lines, as well as unexpected first-aid treatment of POWs in the field. On the other hand, US Army infantryman Bill Foley (TOP RIGHT) had different objectives in the Battle of the Bulge—survive front-line combat when it seemed least likely and, as he sketched into his diary (ABOVE), cope with military protocol when it seemed least practical.

Raiden Dellinger and comrade in France: courtesy of David Mitchell; Bill Foley at training camp and medics sketch: courtesy of Bill Foley.

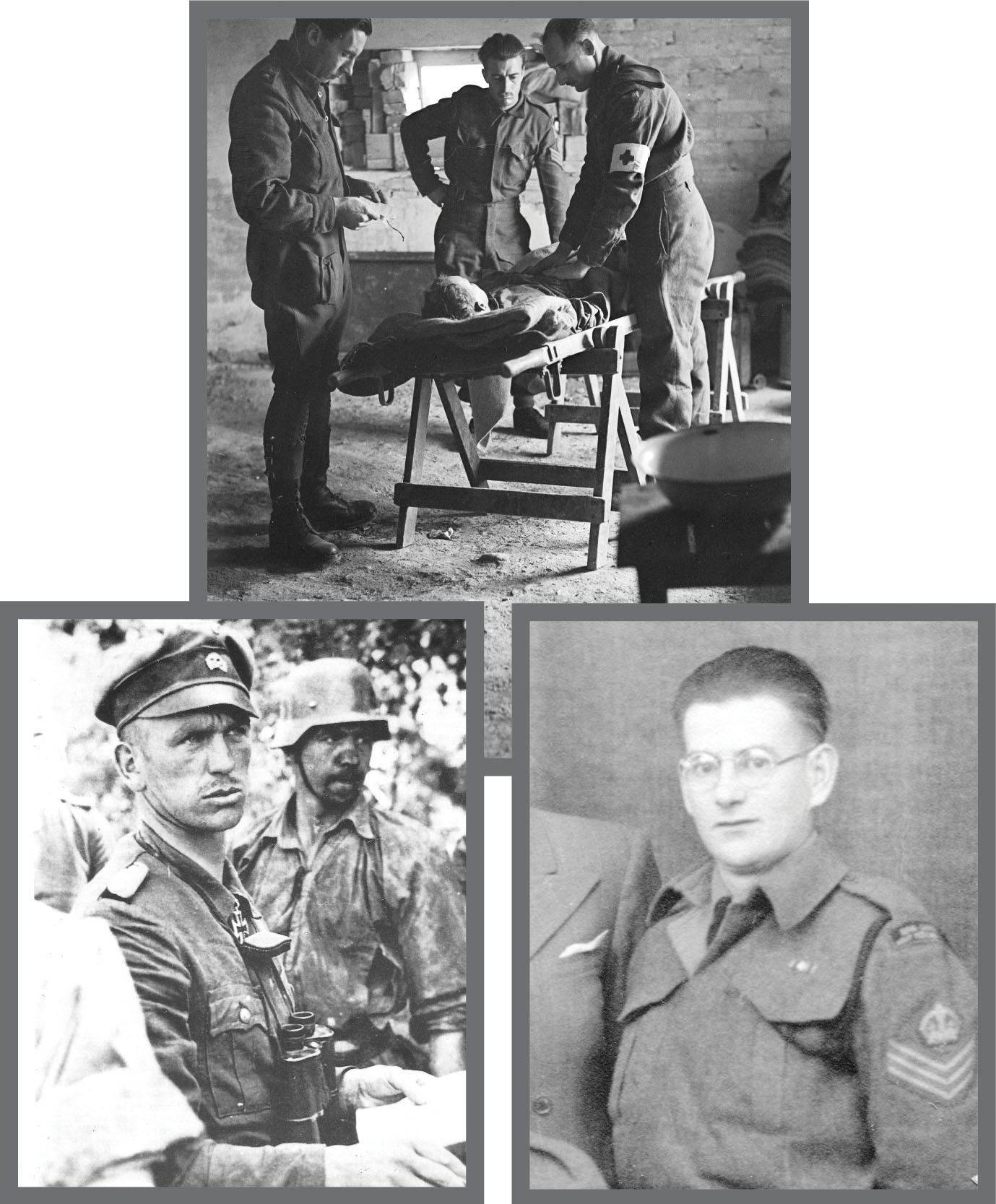

When he landed in Normandy right after D-Day in 1944, Canadian medic Henry Duffield (ABOVE RIGHT) had to quickly establish a regimental aid post (TOP) to attend to the wounded; his RAP was so close to enemy lines that Duffield faced an unexpected visit from panzer commander Kurt Meyer (ABOVE LEFT).

Captured in Malaya in January 1942, medical officer Jacob Markowitz (ABOVE) disappeared into a Japanese POW camp where 50,000 Allied prisoners became forced labour on the “Death Railway.” Over three years behind the POW wire the doctor performed a thousand amputations, 3,800 transfusions, and 7,000 inoculations, all without actual medical instruments.

Personnel of Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps with wounded Canadian soldier: Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN no. 3587617; Kurt Meyer: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing; Henry Duffield: courtesy of the Duffield family; Jacob Markowitz: University of Toronto Archives, John P. Robarts Research Library.

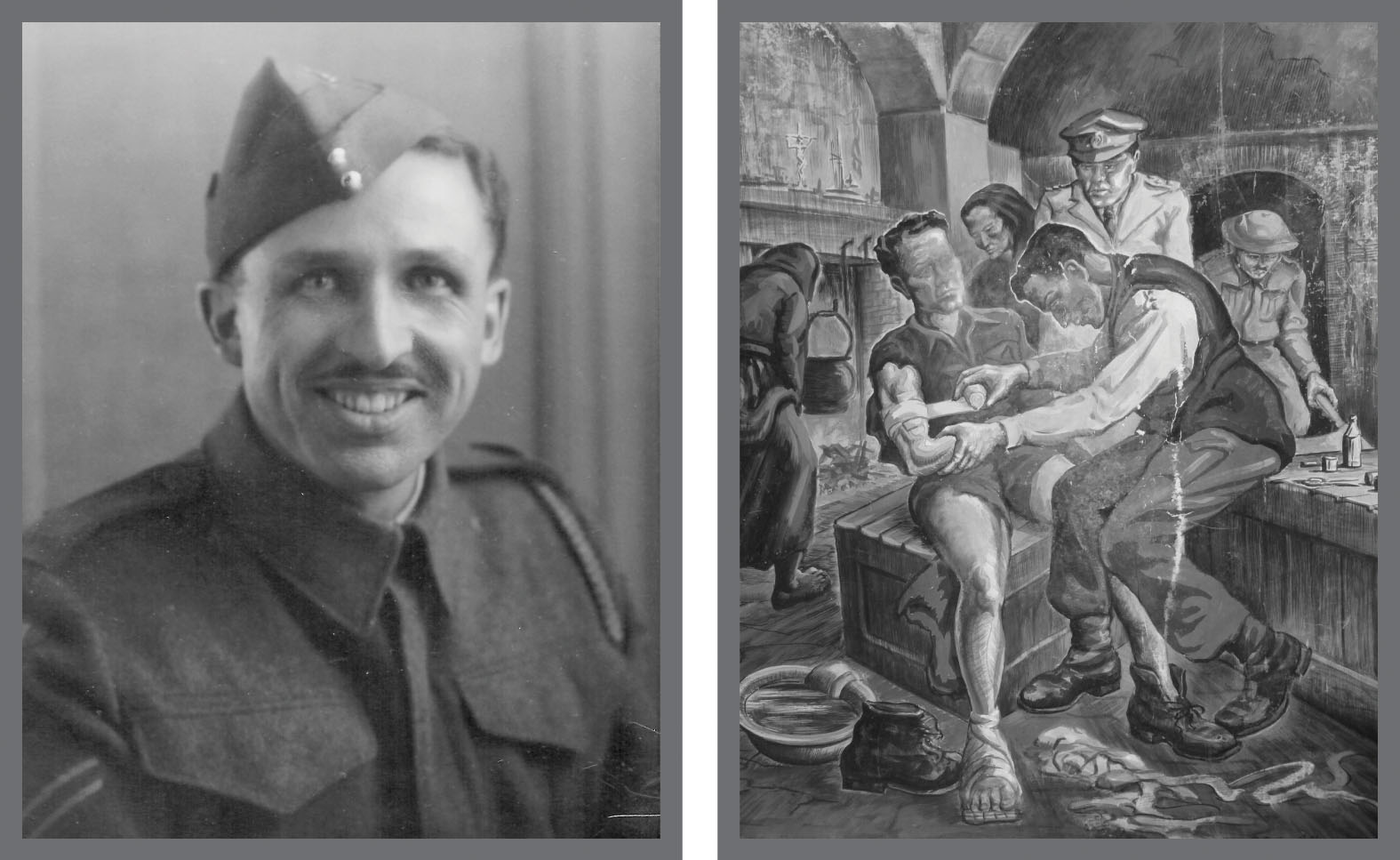

In 1943 medic Arnold Hodgkins (TOP LEFT) tended the wounded in the Italian campaign wherever there was shelter; first as a sketch, then as a painting (TOP RIGHT), Hodgkins captured the experience of attending to a burned tank crewman in a farmhouse near the Moro River.

In 1967, Norm Malayney (TOP LEFT) got his baptism of fire in Vietnam as a medic at the US Air Force hospital in Cam Ranh Bay, near Saigon. Working twelve hours on and twelve hours off through the 1967 US troop surge and the 1968 Tet Offensive, he triaged, packed wounds, and processed the dead in what his comrade called “the worst job in the Air Force.”

Arnold Hodgkins portrait and painting: courtesy of Carol Hodgkins-Smith; Norm Malayney in Vietnam (four photos): courtesy of Norm Malayney.

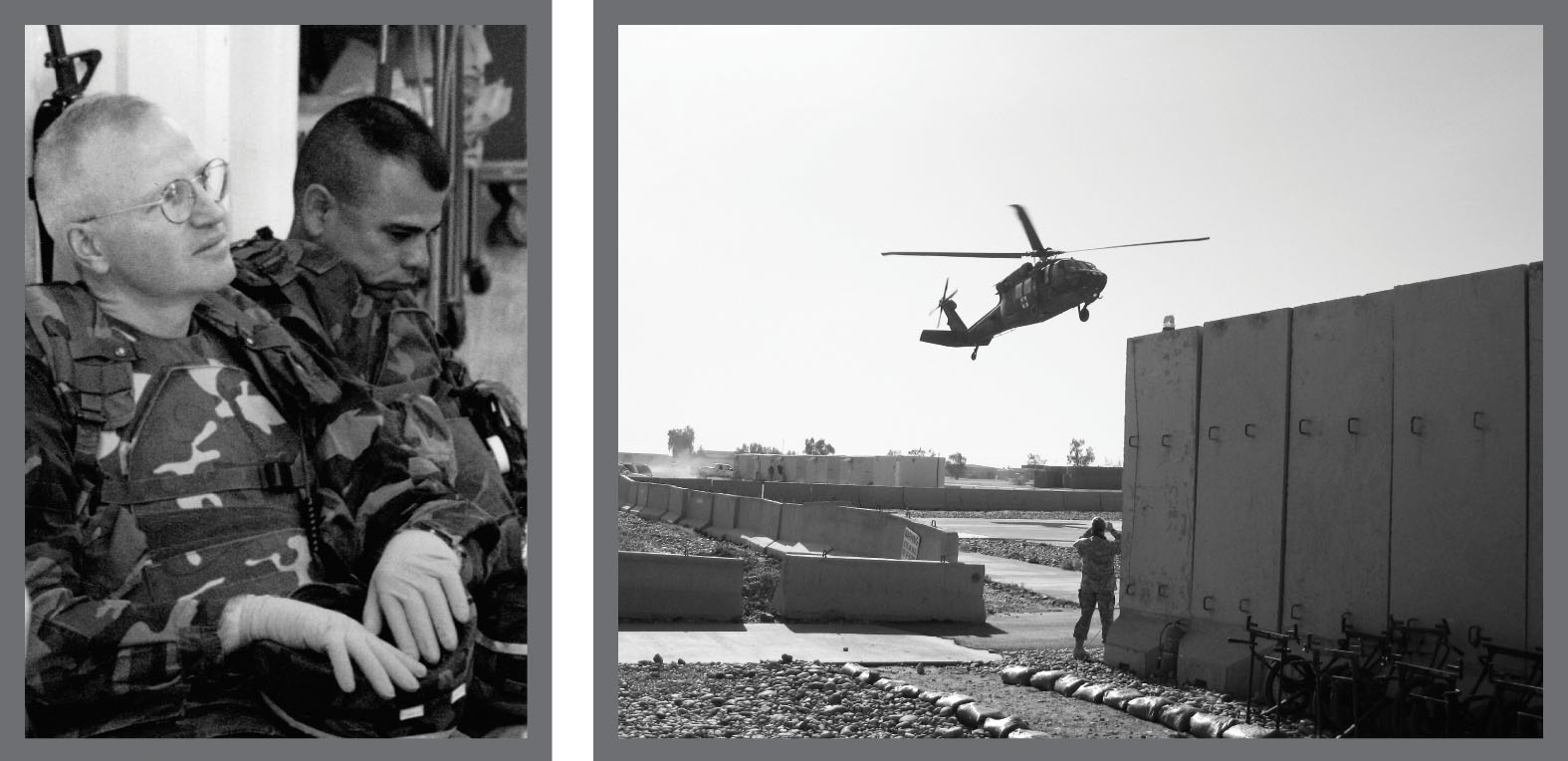

Dane Harden (TOP LEFT, IN FOREGROUND) had already completed overseas deployments for the US Army in Estonia, Bosnia, Kosovo, and Slovenia by 2004, when he began the first of three back-to-back-to-back tours in the Middle East. In Iraq as a flight surgeon, he did much of his service strapped into the midsection of a Black Hawk helicopter (TOP RIGHT), doing emergency medical care on wounded in 110-degree heat as the chopper flew at 140 miles per hour to the nearest base hospital. If a wounded soldier was alive seconds after an injury and a military doctor arrived in that critical time, the patient had a 97 percent chance of survival.

As much as he feared the obvious threats of a war zone—bombs, bullets, and improvised explosive devices—in the Middle East, Herb Ridyard (ABOVE, MIDDLE), surgical chief at a US contingency operating base in Iraq in 2008, worried most about “mass cals” alerts; that’s when the massive number of incoming casualties might overwhelm his surgical teams in the operating rooms. The blurred photo (ABOVE LEFT) illustrates the frenzy of such an emergency. In this case, however, Ridyard watched in amazement as personnel from across the base lined up to give blood (ABOVE RIGHT) to compensate for the threat.

Dane Harden in theatre: courtesy of Dane Harden; Black Hawk helicopter landing, “mass cals” image, Herb Ridyard Jr. in theatre, and blood donation line: courtesy of Herb Ridyard Jr.

By Christmas 1945, medic Joe Reilly (TOP LEFT IN SUNGLASSES AND TOP RIGHT) was home in Philadelphia. But because of his experiences overseas, he couldn’t acclimatize to civilian society until Anne Hubert, a secretary at an elevator company, recognized that all he needed was a chance for a new start. Reilly got a job as a draftsman and his first paycheque and married the secretary.

Administering anesthetics during round-the-clock surgeries with the US Army 116th Evacuation Hospital overseas, medical officer David Wilsey (ABOVE RIGHT) faced a final challenge at Dachau concentration camp in May 1945. Writing home, Dr. Wilsey revealed the horrors of treating thousands of prisoners near death while witnessing the execution of Nazi guards by US troops (LEFT). But none of that trauma was known until 2008, when daughter Clarice Wilsey (ABOVE LEFT) opened a trunk containing her father’s wartime citations, letters, and artifacts.

Joe Reilly and comrades coming home, and Joe Reilly in uniform: courtesy of the Reilly family; Clarice Wilsey presenting talk, David Wilsey in uniform: courtesy of Clarice Wilsey; Dachau concentration camp: Arland B. Musser photo, no. 208705, US Seventh Army.

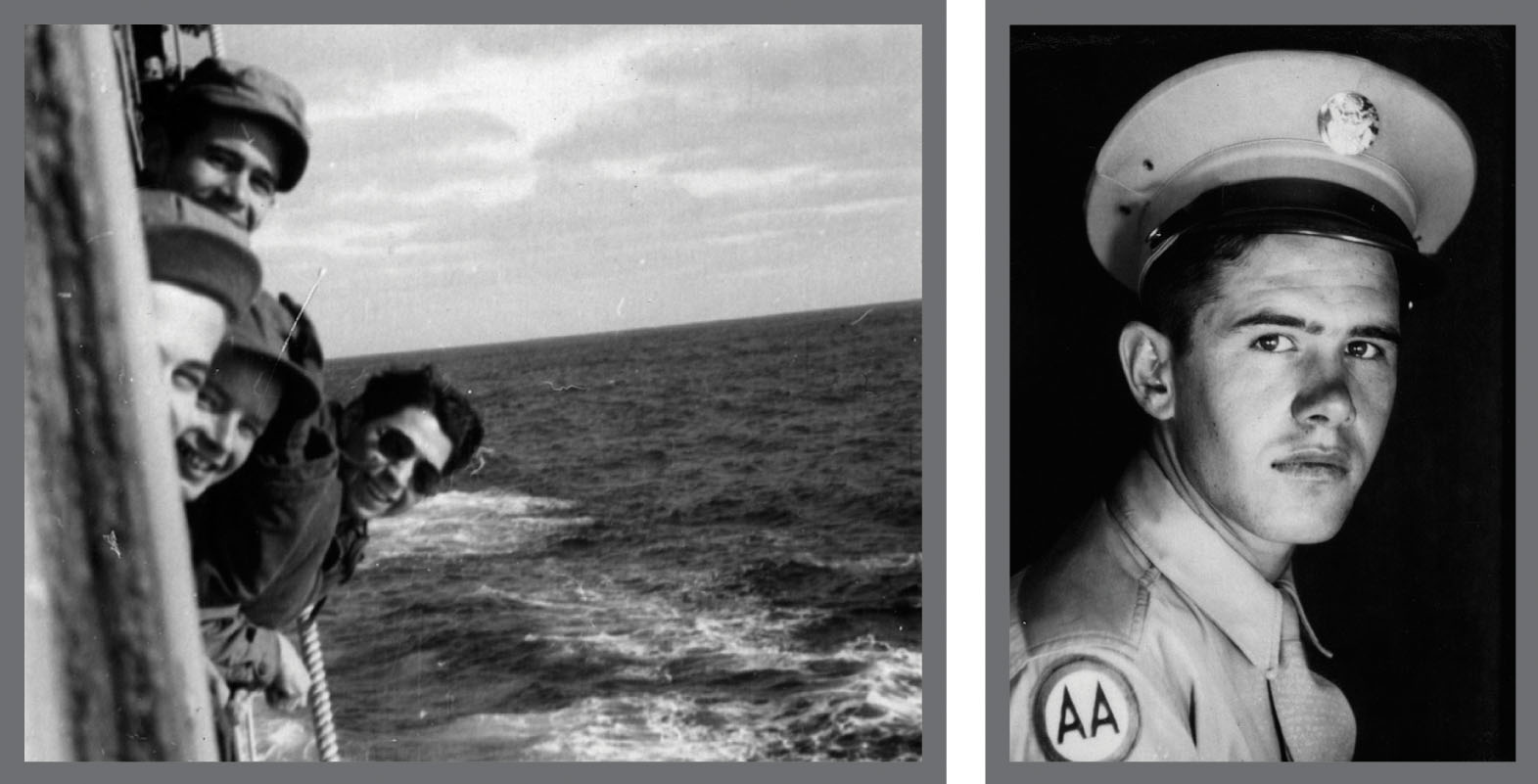

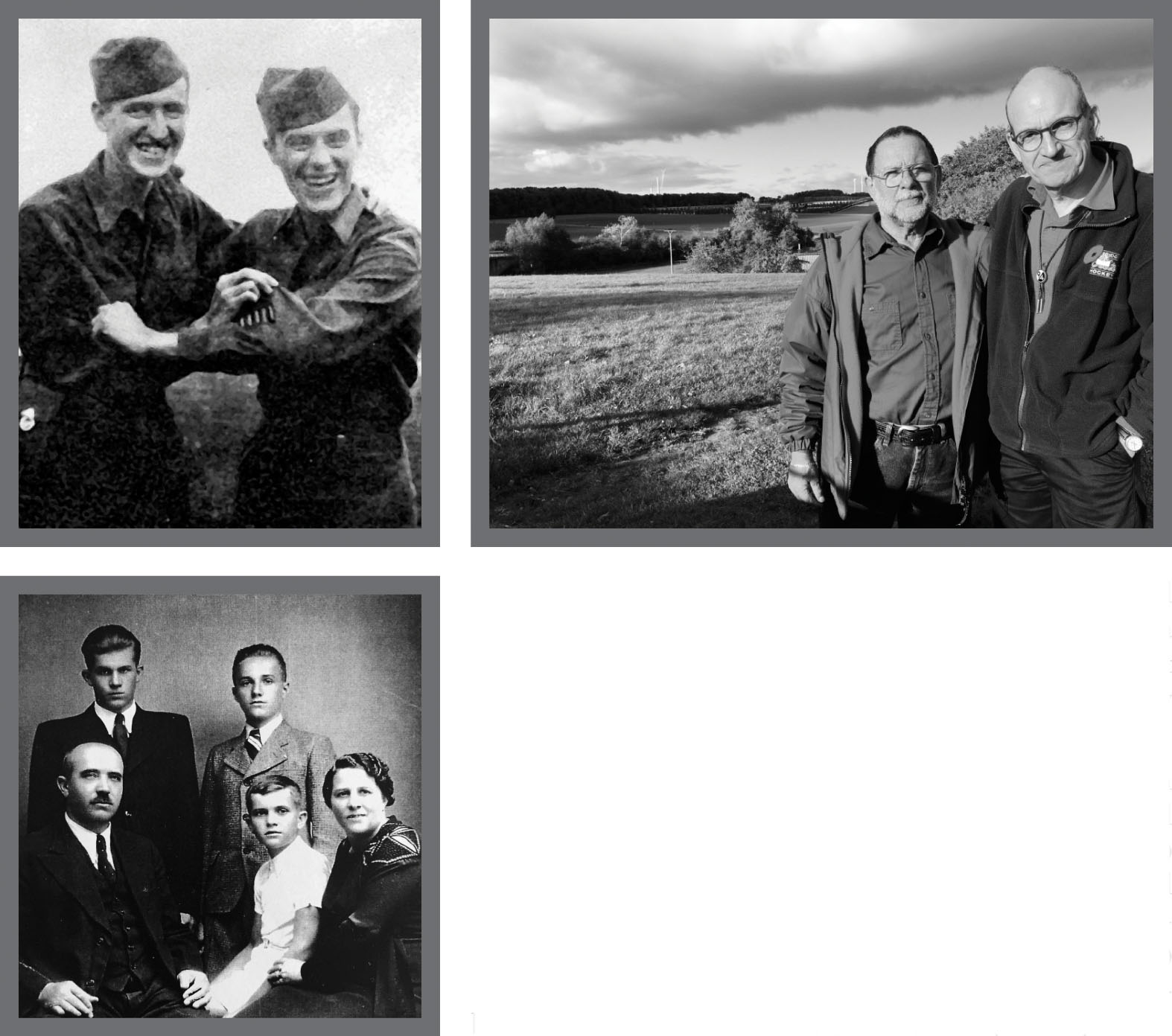

Separated by the war for three years, brothers Alex and Angelo Barris reunited in mid-1945 in Czechoslovakia (TOP LEFT, LEFT to RIGHT) and kidded each other about their service stripes. Meanwhile, the Czech Krizek family (ABOVE LEFT) billeted Alex, to the delight of their three sons.

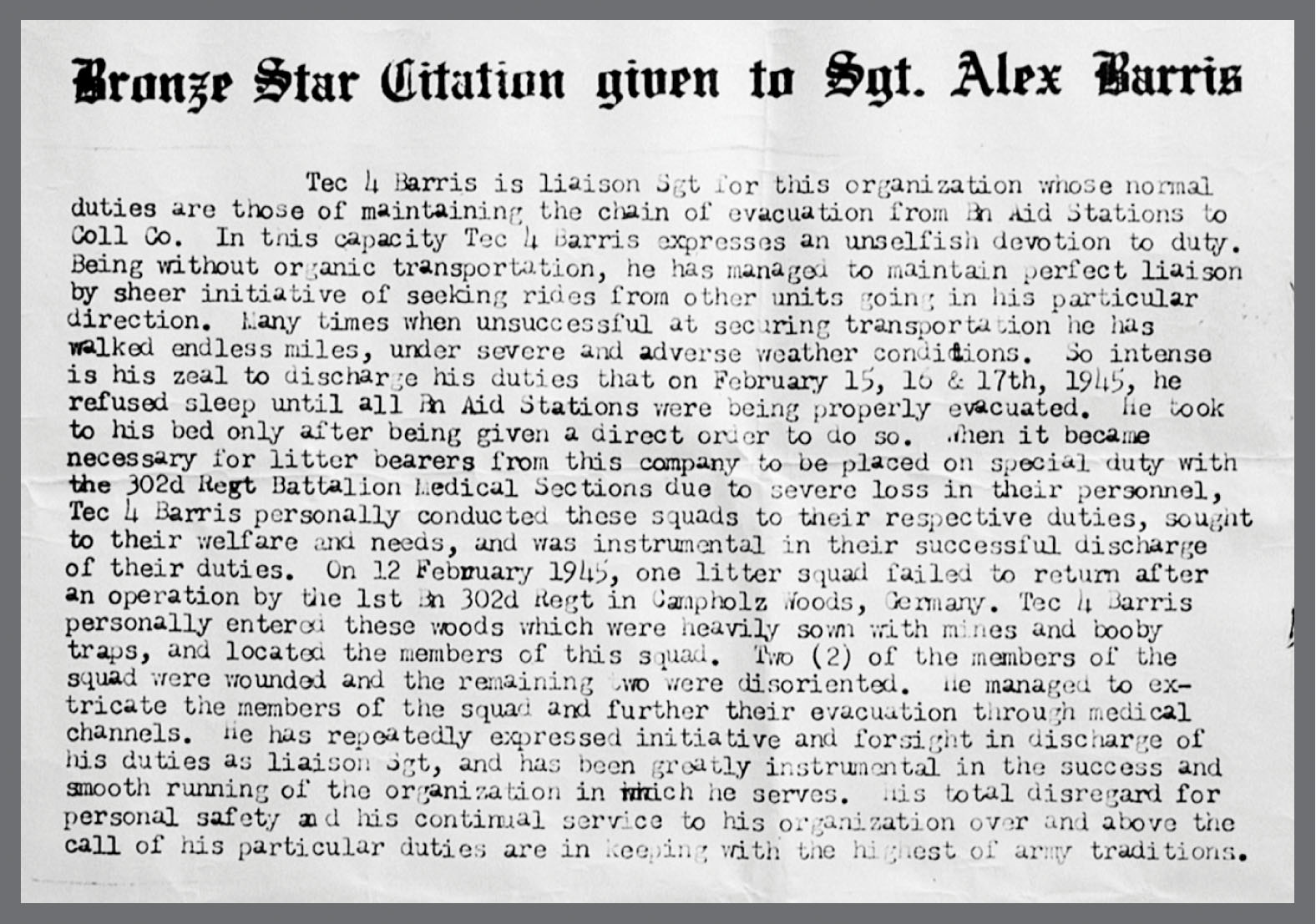

During a 2017 tour retracing the 94th Infantry’s path in the Battle of the Bulge, German-born American Al Theobald and the author (TOP RIGHT, LEFT TO RIGHT) visited Borg, where in 1945 T/Sgt. Barris established a casualty aid station in Theobald’s parents’ farmhouse. In Campholz Woods (TOP RIGHT IN BACKGROUND) medic Barris retrieved four wounded US stretcher-bearers and earned a Bronze Star citation (ABOVE).

Alex and Angelo Barris in Czechoslovakia, 1945, Al Theobald and Ted Barris in front of Campholz Woods, Germany, and Sgt. Alex Barris Bronze Star citation: author’s collection; Krizek family portrait: courtesy of the Krizek family.