IT IS OFTEN said that the Cold War emerged out of the power vacuum left by the Second World War, following the Nazi retreat from a devastated Europe. Yet in Greece the fault line between East and West, between Communist and anti-Communist, was already opening up well before the formal German surrender in the early summer of 1945.

The main Greek Civil War ran from 1946 to 1949, pitting Communist-backed fighters of the Democratic Army of Greece against Western-backed government forces. But our story begins earlier, with the so-called December Events, or Dekemvriana: the Battle of Athens at the end of 1944. This was the prelude to the Greek Civil War, erupting a full six months before the Second World War in Europe came to a close. It marked the first salvo in the Cold War, the opening scene in a drama of global rivalry and antagonism that would last nearly half a century.

The Greek Civil War grew out of a longstanding left–right split in Greek society and an ideological struggle to decide which side would fill the post-war void. The Nazi occupation had been brutal, and the country was in ruins. By 1944, friction between rival resistance groups had already led to armed clashes. But for many Greeks the country’s real heroes in driving out the Nazis were not the members of Greece’s internationally recognised government-in-exile, but the resistance fighters of the National Liberation Front (EAM – Ethnikó Apeleftherotikó Métopo) and its military wing, the Greek People’s Liberation Army (ELAS – Ellinikós Laïkós Apeleftherotikós Stratós), which was mainly controlled by the Communist Party of Greece (KKE – Kommounistikó Kómma Elládas).

EAM supporters saw the end of Nazi occupation as a chance to start afresh. Their goal was to rid Greece of all foreign occupiers and transform the country into a republic – anathema to other right-wing groups, including monarchists, who wanted to bring back the King of Greece from his wartime exile in Cairo and London.

The trouble began in the autumn of 1944. In early October, the Germans retreated from Athens, the last part of Greece still under occupation. Concerned at the extent of Communist support in the countryside, the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, despatched British troops to Athens to secure the city and prepare for the safe return of members of the government-in-exile. They were also there to bolster the authority of the British officer, General Ronald Scobie, who had been put in temporary command of all resistance forces.

When the British soldiers landed in Athens, several days after the Nazi retreat, they were given an enthusiastic welcome. As their military columns marched through streets festooned with celebratory banners, crowds met them with delighted shouts of ‘Inglese!’ and rushed forward to greet them as wartime allies and liberators. But the welcome did not last. By December the mood had soured.

EAM and ELAS partisans considered themselves the main liberators, but now they felt that they were being side-lined by the new provisional government, which the British helped to put in place. What was worse, Greek officers who had collaborated with the Nazis were being rehabilitated. The former resistance fighters accused the British, and particularly Churchill, of trying to reinstate the King against the people’s wishes. In their eyes, the Greek monarchy was tarnished for having cooperated with Greece’s pre-war military dictatorship. Then, on 2 December 1944, General Scobie and the provisional government decided that, rather than integrate the resistance fighters into the Greek army, they would order the disarmament of all guerrilla forces.

The simmering tensions exploded on 3 December, when left-wing demonstrators marched on Constitution Square in central Athens. Trying to control the crowd, Greek police opened fire. British troops were also present and found themselves embroiled in clashes. By the evening at least 28 people were dead and dozens more had been injured.

It was the start of four weeks of mayhem, with British soldiers, backed by tanks and air power, fighting alongside Greek government troops against the same left-wing partisans who only months before, in the fight against the Nazis, had been British allies. Now these ELAS fighters were above all regarded as Communists, in league with Stalin’s Moscow, and a potential danger to Europe’s fragile cohesion. In a pattern that would repeat itself in the Cold War decades to come, the British troops in Athens found themselves in league with strange bedfellows: Nazi sympathisers and collaborators who were also fighting to save Greece from the Communists. It was an even more bizarre marriage of convenience given that the war against the Nazis in Europe was not yet quite over.

Throughout December the battle raged. The Greek capital, having survived the horrors of wartime occupation, was once more engulfed in violence. The city was subjected to constant aerial bombardments by RAF aircraft targeting EAM and ELAS strongholds. The street fighting was vicious and even extended to the temple of the Acropolis, where British paratroopers dodged between the ancient columns to avoid partisan sniper fire. The explosive drama was captured on newsreels, broadcast worldwide by the BBC and other news outlets. World leaders had good reason to follow events closely. Elsewhere in Europe, the last major Nazi counter offensive of the Second World War was catching Allied forces by surprise in the Ardennes Campaign (also known as the Battle of the Bulge). But the Battle of Athens was also a cause for concern, the centre of what now appeared to be a new struggle to determine which forces would shape post-war Europe.

The renewed fighting in Athens caused consternation in London, especially as it pitted British forces against a resistance movement that had only months before been Britain’s ally. Objections were raised both in the press and in Parliament. In a bid to end the bloodshed, the British Prime Minister decided to intervene personally. Winston Churchill arrived in Athens to preside over an international conference on 25 December 1944, Christmas Day, with the hope of reaching a peace settlement.

The conference at the Hotel Grande Bretagne in Athens was a high-level gathering, which included Soviet, American and French representatives, as well as the British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, accompanying the Prime Minister; the Archbishop of Athens, who was the Regent of Greece; and representatives of both the Greek provisional government and the resistance fighters. But from the start it was beset with problems. Hours before it began, nearly a ton of explosives, primed for detonation, was discovered hidden in sewers beneath the hotel and had to be hurriedly removed. Winston Churchill travelled about the city in a heavily plated armoured car, but all the extra security precautions could not prevent one partisan sniper from taking a potshot at him. The conference was abandoned, having failed to achieve a breakthrough.

In early January 1945, the Battle of Athens ended with the defeat of EAM and ELAS forces, who had been heavily outgunned by the British. But atrocities and recriminations continued on all sides, and in 1946 the civil war restarted in earnest, lasting until 1949. At first, it involved British support, until a war-weary British government announced it could no longer afford to shoulder the burden and abruptly withdrew its troops. Then came American economic and military backing for the Greek government, as Allied fears grew that Greece might be taken over by Communists and give the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin a strategic foothold on the Mediterranean.

In fact, for all the Western concern about Soviet expansionism, Stalin showed himself to be remarkably ambivalent, when it came to Greece, about coming to the aid of local Communists. Possibly he viewed the civil war as an insurrection that was unlikely to succeed. Possibly his detachment was part of a broader calculation not to provoke Western ire over Greece and thereby risk upsetting his plans to extend the Soviet hold over other Eastern parts of Europe.

There was also the informal ‘Percentages Agreement’, which he reached with Churchill during a private late-night discussion in Moscow in October 1944. Churchill apparently showed him a handwritten note sketching out a possible plan to divide post-war Eastern Europe and the Balkans into British and Soviet spheres of influence. Yugoslavia and Hungary would be shared 50–50; Romania would be 90 per cent in the Soviet camp and 10 per cent in the British; Greece would be the other way round: 90 per cent British-American and only 10 per cent Soviet. And indeed, several months later in February 1945, when the British and Soviet leaders met again – this time with the American President, Franklin D. Roosevelt – for their landmark Yalta conference to shape a new security and political order for liberated Europe, it was agreed that Greece should remain firmly in the Western sphere of influence.

The Greek Civil War was also important for another twist in the emerging alignment of post-war political forces: its contribution to the split between Stalin and the new Communist leader of Yugoslavia, Marshal Josip Tito, who headed the only Communist government in Eastern Europe to have come to power in the wake of the Second World War without outside help.

A highly charismatic former resistance fighter, Tito had forged close ties with left-wing Greek partisans during the Nazi occupation and was determined to continue supporting them during the civil war, regardless of what Moscow thought. This characteristically independent streak irritated Stalin. In 1948 Moscow expelled Tito’s Yugoslavia from the so-called Cominform, an international organisation of Communist parties designed to consolidate Soviet control over its satellite states in Eastern Europe. The rift moved Yugoslavia out of Moscow’s orbit and left it throughout the Cold War the only independent Communist state in Europe, a thorn in the Soviet Union’s side for years to come. It also prompted Tito to become a founding member of the Non Aligned Movement, made up of countries around the world that stated they were not to be aligned with any major bloc.

As for Greece, American concern at the possibility that it might join the Communist camp was an important factor in the emergence of the policy proclaimed by President Harry Truman known as the Truman Doctrine. The aim of President Truman’s speech to Congress in March 1947 was to explain why the United States had to keep Communist influence at bay in the Eastern Mediterranean by providing economic and military aid to Greece and Turkey. He presented it as an ideological struggle between freedom and oppression, and thus his Truman Doctrine articulated a principle that would underpin American policy towards the Communist bloc throughout the Cold War – that America was the ‘leader of the free world’, whereas Communism represented tyranny and subjugation.

Eventually American support facilitated the Greek government’s victory over the Communists in 1949, placing the country resolutely in the Western camp. In 1952 Greece, along with Turkey, joined the recently established North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO military alliance, defining the ideological balance of power in the Aegean Sea for decades to come.

Western fears of Soviet meddling in the Greek Civil War may have proved unfounded, but the conflict did mark an important shift: the moment when the wartime Allies’ united front against Nazi fascism fractured and Western powers turned to a new battle, to stop a Communist takeover in Europe.

My name is Zozo Petropoulou-Kritzilaki. I was born in 1925 in Patras. We came to Athens when I was seven-and-a-half months old. We were so exposed to danger; we were children, very young. The fact that my generation survived after the Second World War is just luck. Because of the conditions we were living under, we could have been killed 100 times.

When the war started, some British soldiers came to Athens, but I have read that they were little help. The Germans arrested most of them, and they were kept in the Archaeological Museum. We used to save our pocket money to buy biscuits and chocolates, and after school we would go and throw them to the prisoners.

I started being more political when I was 16 years old. First, I became a member of Lefteri Nea [‘Free Young’], which was a branch of EAM. Later on, EAM and all the youth organisations decided to become one, and that’s how EPON [Ethnikí Pánellenios Orgánosis Neoléas/National Panhellenic Organisation of Youth] was created. I was a fifth-year student at the 3rd Gymnasium of Athens and, one day, the school yard was full of flyers, handwritten on torn notebook pages: ‘Young girls, come join Lefteri Nea to drive Nazism from our country.’ We ran and we took them, and we joined Lefteri Nea. You could be in contact with only three people, and just one, the team leader, was in contact with the leading team. I was part of a team with two of my co-students and the leading member, a teacher. She would bring us short texts to write on pages torn from notebooks then throw them around the school and the National Gardens.

At the time, we were listening to whatever news we could. We tried to listen to the BBC because this was what we considered to be a legitimate source of news. So we’d listen to the BBC, then we would write the news on our flyers and throw them around.

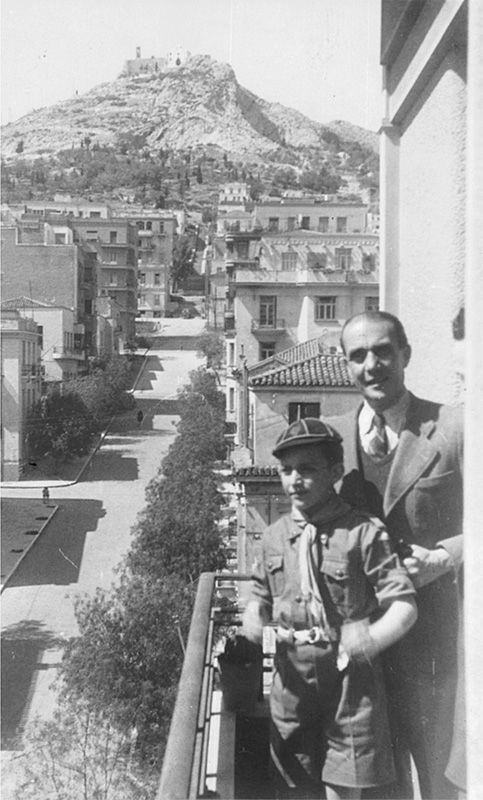

The day that Nicholas Rizopoulos woke up and discovered that the German troops had left Athens was 12 October 1944.

I remember that very distinctly, even though I was only eight-and-a-half years old, because there was this general feeling of exultation and relief. Never before in my life had I experienced this feeling of freedom. And then to go out into the streets and watch all the Greek and British and French and Russian flags and American flags flying from all the various balconies and windows of people’s houses – people in the streets just jumping and shouting and having a marvellous, marvellous time – this is something I will never forget.

I had never heard ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’ before, obviously; that’s not a tune one heard during the occupation. But it was explained to me that this was a very famous tune, going back to the First World War, a favourite with the British public and British troops, and it was a very catchy tune. There were these spontaneous little parades taking place in central Athens in which the bands of the police force and the fire department were going through the boulevards playing ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’. People were singing the lyrics as well, but – as was explained to me later – mangling the English words. People were so happy to be able to sing certain songs that had simply not been allowed during the occupation. This was 12 October 1944. The Germans had left Athens, but the Allied troops had not yet arrived.

We were an upper-middle-class Greek family, but we were basically impoverished. My father was a criminal lawyer, 45 years old. He had married my mother in the early 1930s, and I was an only child, born in 1936. We lived in Thessaly until the Italian invasion of Greece were forced to leave everything behind and move to Athens, where we stayed throughout the occupation. We rented a small apartment two blocks from the British embassy. My parents divorced in the first year of the war, and my mother moved to the same part of Athens, about a 20-minute walk away. I stayed with my father, who introduced me, among other things, to the forbidden fruit of listening late at night on short-wave radio to the BBC Greek Hour. This was completely prohibited, so you took your life in your hands by having an illegal radio transmitter so that you could hear real news instead of what Athens Radio was broadcasting under the direction of the Germans. So I became progressively aware of what was happening in the war.

During the occupation, my father, who was fluent in German, worked for the International Red Cross as an interpreter, which gave him an opportunity to travel all over Greece and thus to have first-hand knowledge and experience of what the various resistance movements were doing and what they were preparing for come liberation. By travelling and talking to the locals, he became absolutely convinced that the KKE and ELAS were up to no good. He was apprehensive and worried and, at heart, very much an anti-Communist. He was one of a small minority of Greek intellectuals who had never bought into the siren song of the ‘Workers’ Paradise’ that the Soviet Union was putting together. He was absolutely terrified at the thought of Greece falling under Communist control, and his anxiety grew and grew throughout 1943 and 1944. He was very well connected and he knew what was already happening in Bulgaria, where the Red Army was in place, and in Yugoslavia and Albania. He was convinced that, unless we put up a fight, Greece too would join the Soviet paradise.

Once the Germans had gone, for a period of five or six days, we had no idea who was in charge. We had barely survived the occupation years. As a young boy, I had this constant feeling of anxiety and insecurity: where was the next meal going to come from? But my father was very kind and reassuring, and he took it upon himself to instruct me. Essentially, the message was this: ‘There are Communists who are going to try to establish themselves as the superior political and military power in Athens, and this would be a terrible thing – we as middle-class people would be in danger if they succeeded in taking over Athens. The fact that the Germans have left does not solve all our problems.’ And so I began to feel much, much better when, beginning on 18 October, the first Allied troops arrived in Athens and the initial reaction from all sections of Greek society was exuberance.

One of those arriving soldiers was John Clarke, who had enlisted at 17.

I wanted to join the Navy, but I was too young. I had no parents, but the recruiter forged their signatures: ‘Here’s your shilling, you’re in the army.’ Happy days … Athens was an emergency trip. We’d been fighting non-stop in Italy for nine months, and we were supposed to be going to Palestine. Then word came that ELAS were marching on Athens and that the royalists weren’t very good at defending, and that’s why we got sent there. Although our advance party were actually in Palestine, the rest of us had to go in a bit of a rush, and we didn’t know who was who, who we were fighting.

The civilians would say hello during the day, then at night time they’d attack us. The old ladies used to have grenades in their bras. One time, I grabbed hold of one – she was shouting and raving, and I just grabbed hold of her. And instead of getting hold of her breast, it was a grenade. And there was this young kid, I’ll never forget it: eight years of age, he was. We were actually billeted in houses near the Acropolis. This young kid starts waving, so we’re waving back. All of a sudden, he rolls a grenade at us – and by the time we see it coming it’s too late to run.

After the Germans retreated, the British came, and they were acting as if we were a protectorate. And this was something that we couldn’t accept because we considered them allies. Since we were allies, why were the British firing in Athens? The whole thing had to do with the fact that the left didn’t want a King. This was the main thing, because Churchill wanted to force the monarchy on us. Until the liberation, I was a member of EPON, but then I joined ELAS, and I was following my unit as a nurse for ELAS.

We knew that EDES [Ethnikos Dimokratikos Ellinikos Syndesmos/National Republican Greek League] was sponsored by the British, and this was not something the other organisations had. Napoleon Zervas and the officers of EDES were getting paid with golden pounds. This wasn’t something that was happening in ELAS. There was a story that at some point the British dropped packages for ELAS, and it was only right pairs of shoes – no left pairs.

By the end of October 1944, Communist elements were trying to impose their views by having bigger rallies and louder shouting. I remember being encouraged by my father to walk through Athens with our housekeeper, to go and see what was going on. I didn’t really understand the subtleties, but I could see that I was supposed to be on the side of the good guys who called themselves Nationalists, rather than the Communists. The Communists were planning some kind of military upheaval to take over Athens. There was this creeping sense of anxiety and fear again.

What happened on 3 December was that the left held a monster demonstration on Constitution Square, forbidden at first but it went ahead. My father encouraged our housekeeper and myself to take a stroll from our little apartment towards Constitution Square to experience one more of these events for my general education. And as we approached, my housekeeper and I heard the first explosions. We never got to the square itself – we were literally less than 100 yards away, and then we saw a crowd rushing in our direction, away from Constitution Square. I heard the noises, I saw the crowds, I felt the excitement and saw the fear in people’s faces as they were running away from Constitution Square in our direction …

After this, my father was in and out of the apartment at all hours of the day and night, and he was filling me with news. Essentially he said a battle for the control of Athens had started between the bad guys, as far as he was concerned the Communists, and the anti-Communists. And we didn’t know how it was going to turn out, but we hoped for the best. He said again and again to me: ‘I am basically optimistic, because I think the British will make sure that the Communists don’t take over the city.’ He also said that we are lucky to be living where we were, two blocks away from the British embassy, because this was going to be a very well-protected part of Athens.

So for the next two or three weeks, while the Battle of Athens raged, mostly I was under lock and key in the apartment. What I could see when I looked out of the window was the most reassuring sight of all: the RAF Spitfires, doing reconnaissance work and dropping bombs in key positions that were occupied by the Communist guerrillas. Inside our little apartment, I could hear mortar explosions, cannon explosions and non-stop gunfire – on and on and on, for the first couple of weeks.

In normal times, it was a 20-minute walk to my mother’s house, but during the battle there was no way that I could safely visit her. The area that we lived in was entirely under British control; the area where my mother lived was okay as well, but in between there were certain parts that were dangerous. Communist snipers had penetrated these areas and were taking potshots at people walking in the streets. So I was not allowed to visit my mother. She, on the other hand, being a brave woman, went back and forth and lived to tell the tale.

Eventually, my father allowed me to go out for a walk, and we stopped to see the sight of a lot of wounded policemen who were arriving at the hospital. My father said these were the people who were trying to protect us. My father pushed me towards one of the open-backed lorries, which were bringing in the bodies from the outskirts of Athens, the bodies of policemen and gendarmerie who had been attacked by the Communists. Some of them were dead and, as I was pushed forward to see these mangled bodies with my own eyes, I saw that there were a couple who were still alive, moaning and groaning in pain. Then all hell broke loose. It was no longer just conversations – I’ve seen with my own eyes things which are shocking.

Towards the end of December, when, unbeknownst to me, the Battle of Athens had already turned against the Communists, we had the famous visit of Winston Churchill.

I was there because I was a registered stretcher-bearer and they wanted someone with medical experience in case anything happened. There was Anthony Eden, Churchill himself, bodyguards and the Archbishop, a big fella. Oh, and Churchill was in Air Force uniform, like overalls.

From nowhere, this bullet came. It flashed by me, and I could hear it hit flesh. I knew what it was right away. And this poor woman in the back of me, her name was Erula, she was about 40, I think she was a schoolteacher at one of the colleges there … Well, they took her body away right away. The airborne troops were out in the street nearby, that’s how they captured the sniper. They spread out and – I think it was about 20 minutes, half an hour later – they came back with this woman. They showed her to one of the military police officers and they took her away in a jeep. She was a Bulgarian girl. I don’t know her name. She was 19 years of age, and she was trying to kill Churchill.

He got up, and he laughed. I’ll always remember: ‘That’ll get me a medal,’ he said.

It wasn’t just Winston Churchill who came under fire during the Dekemvriana. The entire city was a potential death trap, as Nicholas Rizopoulos found out when he visited a friend’s house.

As I was waiting for the door to be buzzed open, I heard this funny noise. Psst, something like that, very near my head. I spent the afternoon playing with him, then I came home that evening and I was told that a sniper had taken a potshot at me. A couple of days later, my father said, ‘Come with me,’ and he pointed at the frame of the door of my friend’s house and there was a bullet hole at about the height of my head. I was amazed, but that was it – I don’t remember feeling suddenly heroic or scared or proud or anything. By this point I’d lived through three months of hysteria in Athens, so somebody taking a potshot at me and missing … Well, I’m glad he missed, but otherwise it’s no big deal.

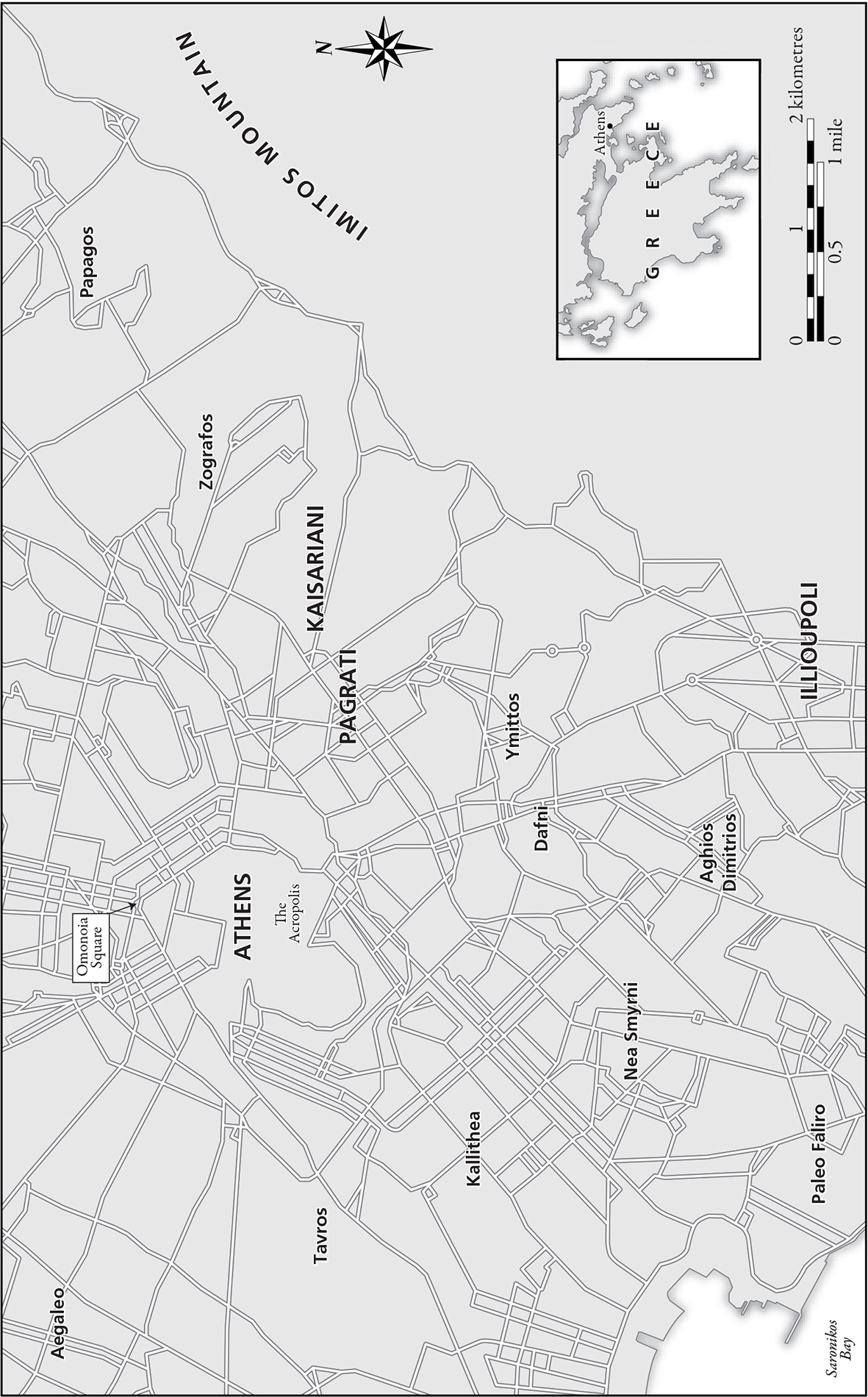

Fights were taking place in Athens, from Syntagma [Constitution] Square to Omonoia Square. All the other areas, from Omonoia to Patissia, there was nothing. In all these areas ELAS was operating. ELAS was responsible for Athens. Even though there were combat units outside of Athens, they weren’t brought to Athens at the time of the Dekemvriana. At least, I never saw an insurgent of the regular army.

At the time of the Dekemvriana, I was at Kaisariani with the Ilioupoli Unit. In Kaisariani, there was a battalion, but the second day of the fights, there were so many injured and dead that it needed and asked for backup, and that’s when the Ilioupoli Unit came. I stayed at Kaisariani until 29 December, when Kaisariani fell. The British planes were firing at people. It was a huge massacre.

On the second or third day after Kaisariani fell, the administration of the unit sent me to Athens, to Ilioupoli, the 6th area, to check what was happening. There were rumours that the injured had been slaughtered, but this was not the case, not yet. I went on my own from the mountain of Imitos to Ilioupoli and from there to Pagrati three times, gathering information. Afterwards, the unit moved outside the Athens area, so they didn’t need me any more. I stayed in Athens until March.

Being involved with stretcher-bearing and wearing the Red Cross, I was walking through the streets of Athens and a gang grabbed me. They must have thought I was a doctor. They took me to a house, and outside the house there were five or six bodies, all dead. They appeared to have been attacked by ELAS, and some of the wounds there … they were unnatural. I’m not one who dreams about these things, I’ve seen too many horrible things in my time, but now and then I sit down and I think about what I saw there …

In mid-January, when the fighting was definitely over and it was safe to walk around Athens, my father said that he wanted to spend a whole day with me because he wanted to show me some things that were important to know. So we did a grand walking tour of the centre of Athens that took us from our part of the city to other parts that had been taken over by the Communists, parts that had been fought over by the Communists and the British troops, and other parts that had been protected by the Nationalist forces. What he was doing was showing me some of the shocking destruction of the buildings – we walked through parts of Athens that I had known as a child, and I now saw them almost completely destroyed. I was shocked because I’d never seen anything like that, except on newsreels.

After the armistice, all kinds of ugly news began to reach us of people who were not lucky enough to live in a part of Athens that was protected by the British forces. They lived in suburbs and outlying areas that were taken over for at least a week or two by the Communists. When the Battle of Athens started going badly for the Communists, on orders from whom we will never know, they took hostages – hundreds and hundreds of hostages. They took them out of Athens and marched them up and down. They killed some of them on the way and killed others later and committed some horrible atrocities.

When news of this reached Athens in mid-January and the first photographs were available of these mistreated human beings, this became the focus of conversation, just discussing these atrocities and what they meant and how lucky we were that we had escaped. Once again, I was invited in to just sit and listen, and I was obviously horrified listening to the details and then also being shown some of these photographs that then were published in the newspapers.

In February 1945, the Treaty of Varkiza was agreed among the different Greek parties, the various paramilitary groups were disbanded, and an amnesty was declared for political offences committed during and after the Nazi occupation. Many former members of those groups were, however, now classified as criminals.

I was arrested one morning out of the blue. I was going to work, and you needed ID to enter. I had ID, and at the time I wasn’t even operating. But they caught me and they asked me to sign a political belief statement. Of course, I didn’t, and I was sent to Chios, which was the first region where a women’s camp was created. I was arrested on 1 March, and on 10 March I was sent to Chios in the second ‘shipment’. When we arrived, we found a few women there. After this, the boats were going back and forth every day, and more women prisoners were arriving. The camps were full and a lot of people were outside, including me. Inside, it was really packed, and by June it was really hot. Rooms that were meant for 30 people were holding 60 to 70.

We stayed in Chios for 13 months, then we were moved to Trikeri. There were around 200 children in the camp at the time. There wasn’t enough water, but there were some wells where they had put some water pumps. We would get water, filling the jugs, and we would walk with that for 200 metres. We had a song: ‘Every woman before dawn goes for water and at night she returns with an empty bucket.’

Then we were moved to Makronisi. They sent the men there first, and they treated them very badly. Some died from the beatings, from the bad conditions. In order to get out of the beatings, some men swallowed their spoons so that they would be sent to the hospital. Thousands of men were sent to Makronisi. A very small percentage survived without signing the political belief statement. A very small percentage. They ordered the army police to take children from their mothers. In order to make them sign, they would take her child, and they said, ‘We are not going to give your child back unless you sign.’

Even though we went through all these awful conditions, I think that it was worth it. We had such strong ideas that we felt that at the moment we were part of something really big.

The fighting continued in the north of the country, and in 1946 the civil war re-erupted. Concerned by the growing Soviet influence in Europe, in 1947 US President Harry S. Truman announced a programme of military and economic aid.

Soon thereafter the Brits were gone, the Truman Doctrine was in place, and a lot of Americans started arriving in Athens. And the conversations are: ‘Well, it’s too bad the Brits have left, but thank God the Americans are coming. And with the help of the Americans not only will our freedom be preserved, but also as the main part of the Civil War is taking place up in the north we have a much better chance of defeating this last and most serious phase of the Communist Civil War with American help.’ And so my whole family and most of my friends were deliriously in favour of the Truman Doctrine.