THE DEATH OF Joseph Stalin on 5 March 1953 paved the way for a sea change in Soviet politics. To Western powers, Stalin, once a wartime ally, was seen by the early 1950s as a dangerously paranoid arch-rival in a global struggle between two ideologically opposed camps. News of his demise generated cautious optimism in Western capitals that Cold War tensions might subside.

For Soviet citizens, the situation was more complicated. Some privately saw Stalin as a monster at the heart of a brutal police state, whose ruthless policies had destroyed lives and ravaged the country. They remembered the upheaval of the early 1930s, when millions of peasants had seen their land seized and been forced into state-run collective farms. They recalled the terrifying purges of the late 1930s, when millions more were denounced as traitors and executed, imprisoned in brutal ‘gulag’ labour camps or banished to remote outposts.

But others looked up to Stalin as an icon of Soviet power who made the country a force to be reckoned with. They saw him as a war leader who had steered the Soviet Union to victory against the Nazis despite extraordinary suffering, and a strong ruler who over the past quarter of a century had successfully transformed the country into a formidable empire, equipped with industrial and military might. For these people, Stalin was revered as a father figure who was virtually a deity. Life without him was almost unthinkable.

The popular reaction to Stalin’s death was one of shock. There was widespread consternation at what would become of the country without his leadership. His funeral was the biggest state occasion in the Soviet Union since Lenin’s death in 1924, and the crowds on the streets of Moscow were so great and impossible to control that in places some people were crushed to death.

Inside the Kremlin, Stalin’s death created a power vacuum. Almost immediately, the main figures at the top of the Communist Party hierarchy moved against the hated head of the secret police, Lavrentiy Beria, who was arrested and executed as a traitor. They then declared their adherence to the principle of ‘collective leadership’, while behind the scenes engaging in an intense battle over who would inherit the mantle of supreme leader.

Nikita Khrushchev was not an obvious first choice, but he managed to side-line his opponents and consolidate his own position to emerge as the front runner. To dissociate himself and the party from the worst excesses of the Stalin years, he ordered millions of political prisoners to be released from the gulag camps and launched an investigation to collect evidence of repression.

The formal ‘rehabilitation’ of Stalin’s victims involved a commission examining the circumstances of each arrest and exposing trumped-up charges. Before long, horrific testimonies began to emerge, collated by the commission, which shone a spotlight on the dark side of Stalin’s Russia. This evidence was one factor that contributed to Khrushchev’s plan to break definitively with the Stalinist past, both to revitalise the party and to secure his own position as Soviet leader.

The place he chose to set out his new stand was the Congress of the Soviet Communist Party in 1956, the occasion when the leadership from around the country gathered in Moscow to set a new course, and to update Communist guests from across the world on policies and ideology. This 20th Party Congress in February 1956 was the first time these top officials had come together to take stock since Stalin’s death. But what the delegates might have assumed would be a routine political gathering turned out to be anything but.

Late at night on 25 February 1956, Soviet officials were instructed to assemble for a private, closed meeting, with all foreign delegations and other guests excluded. Then Nikita Khrushchev rose to address them and for the next four hours delivered one of the most remarkable speeches of the Soviet era: a denunciation of Stalin’s excesses and the personality cult that surrounded him, in a deliberate attempt to destroy the Stalin myth, only three years after his death.

It was an extraordinary change of tack, given the reverence with which Stalin had been treated until then. The assembled delegates listened in bewilderment. Some reacted with applause and laughter, apparently too shocked or confused to take it in. Others were so stunned, they collapsed and had to be helped out of the hall.

Not everyone wanted the speech to be made public. Some of Khrushchev’s more conservative colleagues insisted that it was too incendiary to be released. The text was treated as a top-secret document. But, inevitably, before long the gist of it leaked out, first in reports based on hearsay, then after versions of the text made their way into Western newspapers. The speech was eventually distributed in printed form, so that Communist functionaries could take it back to their regions and read it out for discussion at local – and sometimes turbulent – party meetings.

It became known as the Secret Speech and ushered in several years of relative liberalisation, in politics, in culture, in a new focus on consumerism, and in an opening up to Soviet Russia’s old Cold War enemies in the West. The period became known as Khrushchev’s ‘thaw’, named after a 1954 novel of the same name by the Soviet writer Ilya Ehrenburg.

Among practical measures that eased daily lives was a massive housebuilding programme. This, for the first time, gave many families the chance to live in small individual apartments where they could talk freely, instead of having to share communal flats with neighbours who might be informers. In the cultural sphere, the works of some previously banned writers, musicians and composers, including some from abroad, were allowed to be published and performed.

In 1957 a World Festival of Youth and Students was held in Moscow, bringing 34,000 young foreigners to the city, an unprecedented event. In 1959 millions of Soviet citizens flocked to see the American National Exhibition in Moscow, which gave them a glimpse of what life in the West might be like and fuelled their appetite for more and better consumer goods. The exhibition also provided the backdrop for an extraordinary exchange between Khrushchev and the visiting American Vice President, Richard Nixon, during which the two sparred in front of television cameras over the relative merits of capitalism and Communism. A few years later, Khrushchev personally approved the publication of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s story about life in the gulag camps, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich – a publishing sensation.

But the liberalisation was inconsistent and only went so far. There may have been more cultural exchanges with the West and a relaxation of censorship, but the Soviet Union was still a dictatorship, controlled by the Communist Party and a powerful KGB state security network that monitored both foreigners and Soviet citizens alike. And Khrushchev had no intention of dismantling the Communist system or its control over its satellite states. Only months after his Secret Speech, in late 1956, an uprising in Hungary, which turned into a nationwide revolt, was brutally put down by Soviet tanks on orders from the Kremlin.

In the longer term, Khrushchev’s speech did little to ease international tensions and Western suspicions of Communism. But inside the Soviet Union, the shift away from the repressions of the Stalinist period marked a dramatic turning point in Soviet politics at the height of the Cold War. And though the thaw did not last long – Khrushchev was deposed in 1964 – the process of de-Stalinisation that he began sowed the seeds for some of the thinking that would later be taken up in the 1980s ‘perestroika’ reforms of Mikhail Gorbachev.

Tatiana Baeva’s father was one of many millions denounced as traitors and executed, imprisoned in brutal gulag labour camps or banished to remote outposts.

I was born in 1947 in the small village of Norilsk. We had some political men like Nikolai Bukharin, and this Bukharin had a secretary, and this secretary had a little philosophy society. My father participated in this philosophy society. In 1937, Stalin banished Bukharin, and Bukharin was killed and all people who worked with him were arrested. They were all arrested and killed, except my father. He was arrested, and stayed a prisoner for seventeen-and-a-half years. Sometimes he was in prison; sometimes he was out of prison but could not move to any place. I was born when he was out of prison but could not move to any other place. Before Norilsk, my father was a prisoner in a famous place, Solovki, but Solovki was closed and my father moved to Norilsk, and he worked there like a dog. It is a place close to the North Sea – it’s tundra. No trees, no nothing, no food. Only snow, and half a year it’s night, half a year it’s day. But it was a very healthy place. I like everything what I have in my childhood. Of course, my father was not happy, but I was absolutely happy. Thank you, Stalin, for my happy childhood. It’s a paradox.

In The Gulag Archipelago, the writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn described the beating of a priest imprisoned in the Soviet labour-camp system. This was the father of Tatiana’s future husband, Alexei Shipovalnikov.

My father was a priest, and it was punishable to be a priest. My father was very friendly with [Solzhenitsyn] at that time, and I was too. He wrote a story of my father: how he was in the army during the Second World War; how, after he became a seminarian, he made a big mistake – he went to Bucharest, but he was so Russian he couldn’t stay there. He went back to Russia, and he was arrested and put in a gulag.

I was born in the city of Rostov-on-Don, after my father was freed from prison, but after 13 months we had to escape very fast from Rostov-on-Don because some people came one morning and told [my parents], ‘You will be arrested again.’ During the night, we fled. After that, we travelled.

Nikita Khrushchev’s son Sergei Khrushchev vividly recalls the moment when he heard the news that Stalin had gone.

When Stalin became sick and had a stroke, from the very beginning the doctors said there was no chance of survival. They published this medical bulletin, which showed there was no chance of survival. So, we had this feeling that he would die.

I knew it the same evening it happened. Stalin died about nine o’clock in the evening, and they had this final meeting to elect the new leadership. And then my father came home, sitting on the sofa, very tired, because they’d had two shifts at Stalin’s bedside: day, it was Beria and Malenkov; night, it was Khrushchev and Bulganin. So he sat there and then he told us, without any real sorrow, ‘Stalin died. I’m so tired, I will go to sleep.’ I had the same feeling about Stalin as everyone because I knew nothing about the truth. So I thought, ‘How can he say this?’ Stalin died, and he said, ‘I will go to sleep!’ I went to another room and tried to cry. I couldn’t cry, but I tried.

And next morning I went to the university, and there with the other students we were told we had to go to the Hall of Columns, where Stalin lay, and say goodbye, so we went there. It was crowded, you couldn’t move, just move with the crowd, left and right. I was standing there, they had closed the exits, so you could not disperse, could not go back, could not go forward, from maybe eight in the evening until six in the morning.

My parents were very nervous when I came home late, maybe seven o’clock [the next morning], and they said, ‘Where were you? We looked everywhere, in the police station, in the hospitals.’ We went to say goodbye to Stalin, but we couldn’t do it. My father looked at me and said, ‘If you want to see him, go to sleep, and later I will take you with me and you will look at him as long as you want.’ You had this stream of people who walked beside the coffin. There were many interruptions because the delegations came there with wreaths and flowers. The leaders and members of the family could go through another door, and they had chairs and were told, ‘You can sit here and look as long as you want.’

When I was almost three-and-a-half years old, I was in the children’s hospital. I had diseases from travelling in the very dirty trains. In front of me across from my bed was a huge portrait of Stalin, and when news came that Stalin was dead I started crying, ‘Rah! Rah! Rah!’ I was so happy that Stalin was dead. The reason was very simple: first of all, life was very tough and in my little brain all these travels over Russia from the KGB were personal with Stalin and to live months in the hospital exactly across from the portrait of Stalin, I came to hate him.

The pianist and conductor Vladimir Ashkenazy was a teenage prodigy at the time of Stalin’s death, studying in Moscow.

It so happened that on the day of Stalin’s funeral I had a lesson with my piano teacher. I had to walk through an absolutely silent and stopped Moscow. There was no transportation, not even the Metro, the underground. And so I had to walk for my lesson for about 45 minutes across Moscow to my teacher’s apartment. And I remember seeing lots of old ladies sitting and crying: ‘Oh, our father is dead,’ they were saying. ‘Our father is dead.’ Stalin. To me, it was a bit strange because I couldn’t understand why the attitude was to have such a depth. I couldn’t understand it. I got to my teacher’s apartment. She was Armenian, and I said to her, ‘What do you think will be now with this situation, seemingly such a tragedy for a lot of the population?’ She, in her apartment, whispered in my ear: ‘It will be better now.’

Then those people who were in the Politburo next to Stalin became the government, with Khrushchev probably already being more important than others. I think Malenkov and some others tried to become number one but, in the end, Khrushchev won. We weren’t aware, of course, of all the goings on between the important people at the top.

During the Cold War, if you had your adversary, you created an image that you thought would work for you. So, to the West, especially in America, it was confrontation: Khrushchev was an unpredictable, emotional, very aggressive person. But in reality that was absolutely wrong. He was very warm. He was emotional, like all of us. He was enthusiastic about this own country, like any good politician. He said that his goal was not victory in the Cold War: he wanted to make the lives of the Russian people better. So in politics he was focused on agriculture, on housing and on consumables. He was a good family father; we loved him and he loved us. He liked culture. He visited theatres maybe two or three times a week. He liked opera; he didn’t like ballet – for him it was too boring. He liked nature, going walking in the woods, picking mushrooms in the autumn, or just swimming in the Moscow river. It was very different then: there was no wall of bodyguards. His mansion was the official residence; there was an old wooden fence with a small gate. He would open this gate and go out, and all the Muscovites would be sitting on the grass around there, and he would be saying, ‘Hello, hello, how are you?’

His relationship with Stalin was different. They grew up in politics together. At the time of the revolution, Stalin was a bureaucrat. My father was not in the movement before the revolution, so he was not affected by Trotsky. When Stalin started to fight for power, my father was in Moscow because he wanted to study to be an engineer, and he supported Stalin strongly. From his point of view, Stalin was the most reasonable person, because all these revolutionaries were so theoretical and didn’t really have an interest in the real economy, in the real things that happened in the country. In the late 1930s, he became very negative towards Stalin, and this negative feeling grew during the Second World War because it was clear to him that it was Stalin’s fault – it was not the generals who were not prepared for the war. Stalin thought that he knew better than his generals. After that, he was very critical about Stalin.

When Stalin was dead, my father was immediately freed, and we went to Moscow. It was the first time I saw cars and big buildings and culture and movies. We have nothing but what the government gave to our family and another family: a flat, and some possibility for my father to begin work as a scientist.

At Moscow, I had some problems at school because the teacher asked me, ‘Where were you born? Who is your father? He was a prisoner – he is guilty.’ Slowly, I began to understand.

After Stalin, the Communist Party decided, ‘Okay, you can go – go, you’re rehabilitated now, go.’ But in the community, you’re forever Stalin’s prisoner. Can you imagine, you’re back to an apartment and you figure out that the man next door is the person who put you in prison 20 years ago? It happened all the time. It was sometimes the price for freedom. People understood what they were doing: they wrote a letter about somebody; they knew exactly that this person did nothing, but it was the price for freedom.

After Stalin’s death, my father said, ‘We have to tell the truth to the people. If we want to build the best society in the world, where everybody will be equal, you cannot live in paradise surrounded by barbed wire.’ So, he exposed Stalin’s crimes, and I think that was his big mistake in domestic politics.

The main thing that Khrushchev did was transform the structure of power from a police state, where you rule through the secret police, to a normal bureaucracy, like it is in any democratic or even authoritarian state. It is the beginning of freedom. All these new poets like Yevtushenko and others, the new composers emerged then, the writers. It was the beginning of the boom in science; at that time, there were more Nobel laureates in Russia than before and later. It was the beginning of development in chemistry, in agriculture, in missiles industry, in aircraft industry, in everything. The level of life started to grow. More than half the population of Russia improved their living conditions. Before, they lived in rooms, like this, 20 square metres with six, seven, eight people. And then people started to live in their own apartments. Small apartments, but their own apartments. It is difficult for you to understand what does it mean if you live ten families in one apartment, with one bathroom, and in the morning you are waiting and waiting and waiting and waiting until you can access the toilet. So, it was the beginning of the boom in the new families.

When Khrushchev made his famous speech after Stalin’s death, it was 1956 – I was 19 years old. At that time, being already quite a well-known young musician, I was not terribly interested in other things. I understood that this was a Communist country where I lived and the rest of the world was quite, quite different, but I never gave it too much thought. I was a musician, and a successful one, and they sent me abroad, I was very happy and pleased that I had seen the world a little bit, and it never entered my mind to think what could happen and what should happen and what my country was like. It came later.

I wasn’t terribly aware of the history of the Soviet Union because the availability of material from which you could learn the truth of what really happened wasn’t there. When I went abroad, I could learn a little bit, but not very much because I was very busy practising and playing concerts. So my knowledge of the past of the Soviet Union, how the system came around in 1917, all the details and all the unbelievable executions and everything – I wasn’t aware of everything. But in 1956, it looked like life was a little bit freer, people could talk to each other a little bit more, not afraid to say this or that – that I could feel.

As Sergei Khrushchev recounts, at the 1956 Party Congress, the assembled Communist delegates listened in stunned and bewildered silence to Khrushchev’s speech.

It was emotional. He told them, ‘We committed these sins, all of us, so we have to confess. And then, after, if we’re forgiven we can go forward with clean hands, though we will live with these sins all the time.’ So, he had this feeling from his soul that we have to say the truth.

So, they kept the speech secret, and I learned about this only when it was exposed and all these rumours began. I saw this small red brochure on my father’s desk in the apartment, and I looked at it, and my father saw me and said, ‘If you want, you can read it.’ And I read it, and it was a shock.

I was with my father in London in April ’56 and I was shocked because Stalin taught us that all of [the people] are very poor, and then I saw it was a very different picture. In one reception, a man asked me about [the] speech, and I was young, and he asked what the reaction of the people was? And I said it was different, but not so different; I answered diplomatically, so I thought. And then I told my father next morning, ‘This gentleman asked me this question, and I answered.’ And my father said, ‘Ah, you did the wrong thing, you mustn’t talk about this at all,’ because at the time it was still secret. ‘You’re not thinking about the subject, you’re thinking that it was exposed, and then someone will report and then hard-liners will say your son just discussed this secret speech with some capitalist in Great Britain.’ So he thought more about me than about the secrecy of the speech.

First of all, it was a secret report of Khrushchev and the extra last day of the Congress of the Communist Party. We didn’t know about it – it was secret because it wasn’t public. When it happened, in 1956, nobody knew. It was about 1957 the rumours started: something had happened upstairs, in the Politburo, in the Communist Party. But everybody was guessing only – nobody knew what had happened. Until, I believe, 1959 or 1960, some information started leaking. It was again leaking information, it wasn’t a real share of this information from the top. Finally, the secret report of Khrushchev about Stalin became public.

Somebody found this text. But there were big suspicions that it was not real. First of all, the language was very ‘high’. Khrushchev’s language was usually very low-level, not intelligent language. It was very strange – it was not Khrushchev’s language. So people didn’t trust this paper when it was found. Some dissidents very famously said, ‘No, it’s not real.’ But when it was finally published, the people who found this copy were right – it was real. So, who wrote this for Khrushchev? We still don’t know. But this secret report did something good for us.

It was very important because it was like a great revolution. People changed their minds, and there was more freedom. Khrushchev did a very important thing. Beria was the KGB chief and right hand of Stalin, and he was very close to succeeding Stalin. But Khrushchev was very smart: he talked with people and they arrested Beria immediately. If Beria had stayed, it would have been a bad story for Russia.

I don’t think that Khrushchev was so smart – I think he just cared that Beria would be first. Khrushchev was absolutely equal to Stalin in power but not in the brain. When Khrushchev became a dictator, it became a very tragic time for the Church to which I belonged. In 1957, yes, of course, a lot of people were freed from prisons and concentration camps. Although, of course, people could be happy they were free, but we were very poor, absolutely poor. To understand what it means to be poor, for example, when my sister and I were at school we had only one coat for two of us, one pair of shoes for two of us. We had two shifts in the school: she had afternoon shift and I had morning shift, and when I came home from school I had to give her the coat and the shoes.

I had a lot of problems. Problems started in school immediately because my father was a priest. 1961 was a terrible time for the Russian Orthodox Church. They not only closed the churches, they started to blow up the churches. A lot of very famous churches were destroyed at this time. And that’s my memory about Khrushchev. There was a lot of trouble, not only for the Church. There was the time when Solzhenitsyn and others were published, but it was a very brief time. After, it became a very tough time again.

It was only ten years after the war, and the country did not recover so fast under Khrushchev like was expected. After the coup in 1964, when Khrushchev was dismissed and Brezhnev became leader, at one point it was a healing. But after it was stagnation. Life was in the middle – not perfect, but not worse.

The Soviet Union was still a dictatorship controlled by the Communist Party, and a powerful KGB state security network monitored both foreigners and Soviet citizens, as the young pianist Vladimir Ashkenazy found out.

In 1958, when I was 21, I had my first American tour as a pianist. I had good reviews. It was unbelievably successful for a chap of 21. I couldn’t travel alone; at that time, people who went for tours of this type would have to have a companion from the Ministry of Culture, or whatever ministry it would be – basically, of course, a KGB chap. This chap who went with me had no idea, had never heard the name of Beethoven or Mozart – he was an absolute moron. But he had to watch me because he would have to report on our return how the tour went. The tour was very successful, but he wrote a negative report about my behaviour. He said that I never expressed in my interviews or in contact with Americans pride at being a Soviet citizen. Can you imagine? He submitted his report to the Ministry of Culture. I was called to the ministry a few weeks later and I was confronted by this chap, and the head of the Department of Foreign Relations read his report to me and said, ‘Well, what do you say to that?’ I didn’t know what to say; I was taken by surprise. I said, ‘I can’t understand. I think I behaved very well. I never did anything that would be considered damaging to the image of the Soviet Union, so I can’t understand why this chap wrote such a report. I had a successful tour, I made many friends with American musicians, and I can’t understand why he has written this.’ The chap said, ‘Well, whatever it is, we have decided now you don’t go abroad for a few years. You might as well play your recitals for the workers and peasants of our country.’ That’s what he said. Just a slogan. What could I do?

The chap who was the head of the party department in the conservatory was there at the meeting too. His name was Kurpekov. He was a bassoon player and a very nice man. I had played with him. He came out of the ministry with me, and said, ‘Don’t worry, don’t worry, I don’t think it will be that bad. What could I do? I couldn’t say anything. But you know it will improve. Don’t worry, I will always support you.’

In 1962, when John Ogden and I won the Tchaikovsky Competition – we shared the first prize – we were asked to attend a reception in the Kremlin, with the presence of Khrushchev and Brezhnev and all the party members. It was quite an experience. Imagine, we are in the Kremlin, and Khrushchev and all those important people are coming and shaking hands with us … I’ll never forget it.

I married a ‘capitalist’ in 1961 – an Icelandic ‘capitalist’, can you imagine! Then the Ministry of Culture told me quite officially, ‘If your wife doesn’t become Soviet, you will have no career.’ So two days after we married on 25 February, after the weekend, she applied to become a Soviet citizen.

Because of my first prize in 1962 (the Tchaikovsky Competition), I was allowed again to travel abroad to perform concerts. In 1963, I was invited for the first time to England. My wife had lived in England with her family from 1946 onwards, and naturally we wanted to go together with our young son on this trip.

As we had already discussed the possibility of remaining in the West back in Moscow (outside in the middle of the street), when she said, ‘I’m not going to go back’ I was fully supportive. I was granted permanent residency in the UK by the British authorities, based on my wife’s having been resident in London for fifteen years, so when we decided to stay in England, it was a shock to the Soviet authorities.

My wife and I decided to come back from the UK to Moscow for what was initially supposed to be a ten-day trip, but we decided to leave our very young son in London. That was a very wise thing to do! When we arrived in Moscow, my international travel document (foreign passport) was taken away (my wife refused to give hers up) and I was left with my local Soviet identity card only. We had to spend about six weeks in Moscow, I played some concerts, and we just didn’t know if we could leave or not.

At the Ministry of Culture, quite by surprise, a very nice secretary said to me, ‘I know you are getting a little anxious, waiting to see Furtseva (the Minister of Culture). Don’t worry, it should be alright in the end, but you never heard it from me …’ Apparently, Furtseva went to the top, to Khrushchev himself, who decided it was right to let us go. Finally, I got the call from Mrs. Furtseva’s secretary, saying that the Minister of Culture wanted to see me. When I saw her, she said to me, ‘So when are you leaving?’ Just like that! I was amazed. I realised that she had been given the okay from Khrushchev personally. I went to the passport office. ‘My passport,’ I said. The officer looked at me as if I were an enemy of the people. Five minutes later I had my passport back. So of course we left for England. In his memoirs, Khrushchev mentioned this particular incident and said that he remembered meeting me at the Tchaikovsky Competition and he thought it just about the right time for our country to make some of its citizens much freer, and in this case I should go back to London. We didn’t go to the Soviet Union for 26 years after that because I didn’t trust them.

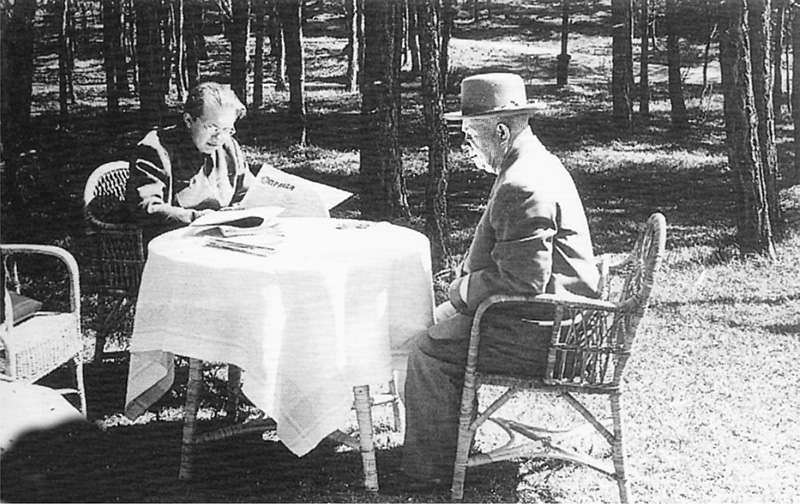

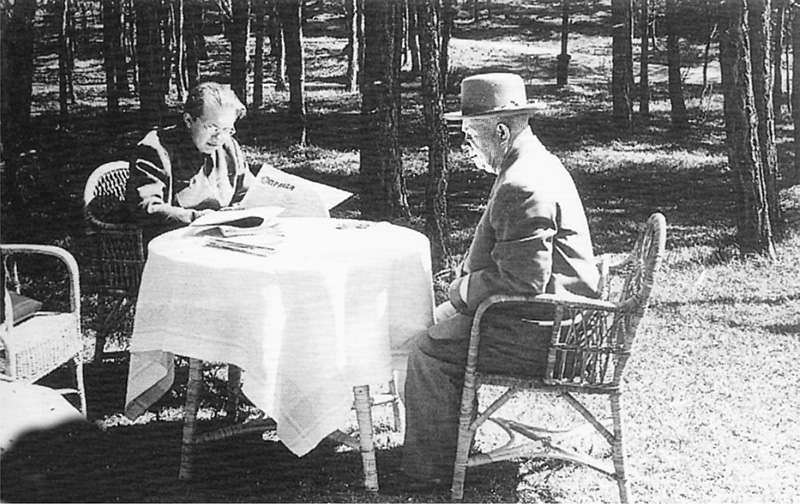

After he was deposed in 1964, Nikita Khrushchev lived in internal exile until his death in 1971, shunned by the authorities, and undisturbed except for the occasional visitor – such as Tatiana Baeva, who in 1965 knocked on his door with a friend.

It was 1 May, a year after he lost power; 1 May was a great Soviet holiday, and some people went to Red Square, but some people stayed at home and drank vodka. I was with the people who drank vodka. We sat and talked and drank and talked about history, and suddenly somebody said, ‘Let’s go to Khrushchev’s dacha.’ Probably he worked at Pravda, and he called somebody, the KGB, I think. And we went to Khrushchev’s dacha.

He met us at the front door, double security there, and invited us into the house. It was huge territory, but the house was small, regular. We sat down in his dining room. Inside the room were two KGB security men, and Khrushchev told us that they stayed all the time in his house, they never went out. And we talked with Khrushchev. I just saw a very small man who looked like – you know in the English garden, you have some small statue with a big head? – he looked disappointed. He had lost all friends, he had lost everything. I asked him about the secret paper and about how many secrets were open, and Khrushchev said, ‘Oh, it’s many secrets we have, but I cannot talk about this.’

I asked him about Pasternak. He wrote Dr Zhivago. Khrushchev was against Dr Zhivago – he forbade it being published. I asked him about it, and he said, ‘Oh, I was wrong. I was against it, but I never read Dr Zhivago. Now I have read it and understand that it’s a good book, and I’m very sorry about this.’

I am against revenge. My father was against revenge. Many KGB people now in prison helped my father. When you have tyranny in your country, people help each other a lot.