THE FIRST TWO decades after the Second World War were not only marked by the emergence of the Cold War. This was also a period of intense decolonisation. Between 1945 and 1960, three dozen new states in Asia and Africa won limited or full independence from colonial rule, in parallel with and sometimes shaped by deepening superpower enmity. In fact, an aversion to colonial rule was one thing that the Soviet Union and the United States had in common: both were keen to see exhausted post-war European powers like Britain, France and Belgium relinquish their colonial possessions.

Moscow backed decolonisation for ideological reasons (to liberate oppressed peoples from their colonial masters), but also for geopolitical ends (the hope that it would allow the Soviet Union to extend its influence and cultivate new allies). The United States, a former colony itself, was likewise sympathetic to the principle of national self-determination. It was also keen to see the emergence of potentially profitable new markets.

But as the 1950s progressed and Cold War rivalry increased, first the Truman and then the Eisenhower administrations began to worry that the withdrawal of European powers from their colonies would limit access to precious raw materials, and might also prompt takeovers by pro-Soviet Communist parties, shifting the international balance of power in favour of the Soviet Union.

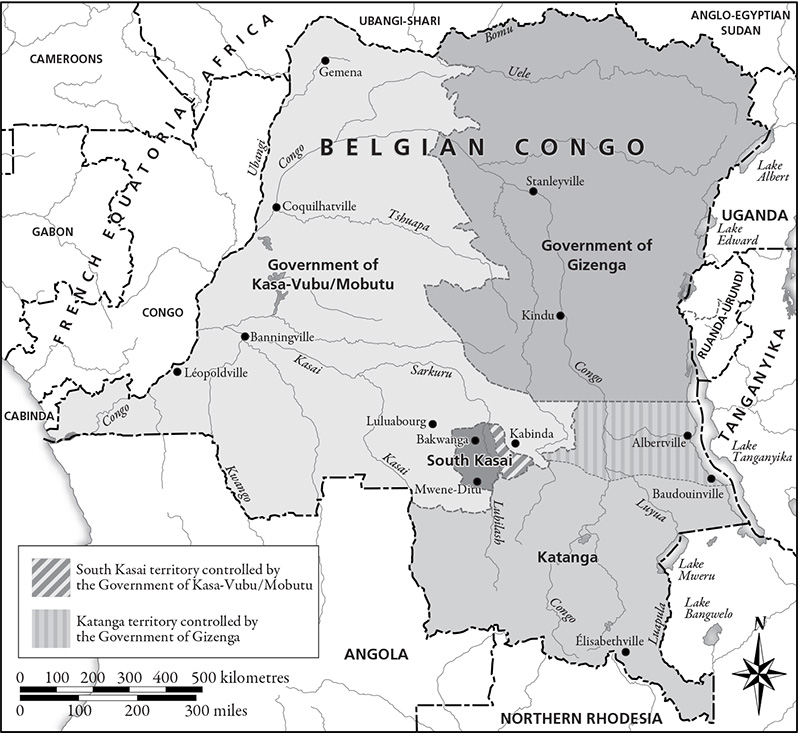

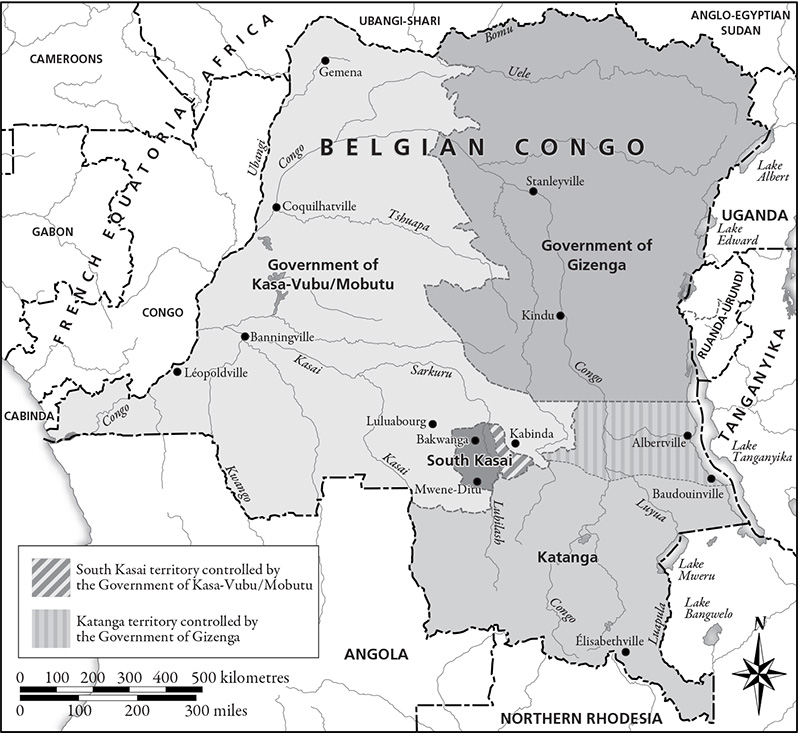

One case in point was one of Africa’s most strategically important and biggest states, the country then known as the Belgian Congo. The so-called Congo Crisis was an early example of the type of proxy war, driven by local tensions but exacerbated by Cold War competition, that in later years would become all too common.

The Congo had been under Belgian control since the late nineteenth century, subjected to a rigid colonial regime with a high degree of racial segregation. By the 1950s the évolués, as the growing ranks of Europeanised and educated urban middle class were called, were becoming impatient. A nationalist movement, made up of different and opposing factions, was gaining momentum.

In 1959 protests by Congolese nationalists demanding an end to colonial rule descended into violence and put Belgium into a panic. In January 1960 the Belgian government convened a Congolese Round Table Conference in Brussels to discuss the country’s future. The Congolese nationalists present pushed for new elections and an early date for independence – 30 June 1960 – but the meeting left unresolved tricky issues, such as the balance of power between central government and key provinces.

One attendee – released from prison to join the conference – was the charismatic left-wing leader and one of the founders of the National Congolese Movement or MNC (Mouvement National Congolais), Patrice Lumumba. Several months later, in May 1960, his coalition having won the largest number of seats in the National Assembly, he was elected the country’s new Prime Minister, having campaigned on a nationalist platform for an independent Congo that would be a unitary state, sovereign and in charge of its own resources.

These were contentious issues. One of the largest countries in Africa, the Congo was rich in highly prized mineral deposits, including the uranium needed to produce nuclear bombs. This made it an attractive prospective ally for either of the two superpowers, both of them now armed with nuclear weapons. Who controlled the mines was also a delicate political question. The resource-rich provinces of Katanga and Kasai, and their allies in Belgium, the United Kingdom and the United States, were worried that Lumumba’s central government might nationalise the country’s valuable mines and deny them access to a crucial part of the local economy.

On 30 June 1960, Independence Day was marked by a grand ceremony in the capital, Leopoldville. But when the guest of honour, King Baudouin of Belgium, rose to speak, he shocked some of the Congolese politicians present when he praised the ‘genius’ of his ancestor King Leopold II for colonising the Congo and depicted the handover to independence as the successful end of a ‘civilising mission’, glossing over the millions killed and oppressed during the years of colonial rule.

The new Congolese President, another nationalist leader called Joseph Kasa-Vubu, duly thanked him. The more radical Patrice Lumumba, the new Prime Minister, was not so diplomatic. He delivered an impromptu and scathing rebuke to the Belgian King, pointing out that the Congolese had fought for independence ‘to put an end to the humiliating slavery which was imposed on us by force’. His speech, broadcast on the radio, was greeted enthusiastically by many listening across the country.

But not everyone was a fan of Lumumba. In the far south-east of the country, Katanga Province was already agitating for more autonomy from central government. And it took only a few days for more general discontent to emerge, as high expectations of immediate change were not met and swiftly turned into frustration.

The Congo Crisis began with a mutiny in the security forces, initially among units who had expected that independence would translate into instant promotion and higher pay for Africans and were angry to find themselves still being commanded by the same white colonial officers. The mutiny soon turned into a wider revolt, which Lumumba’s new government was unable to contain, and the country descended into chaos.

On 10 July, without seeking permission from Lumumba’s government, Belgium sent in paratroopers to protect fleeing white civilians. Before long, Congolese government troops were clashing with Belgian forces. Adding to the mayhem, Katanga and South Kasai provinces – both keen to stop Lumumba’s government taking control of their assets – declared they were seceding, offering lucrative mining deals to Belgium in return for its backing.

Lumumba appealed to the United States and the United Nations. The Americans declined to side against Belgium, a NATO ally. The United Nations sent in peacekeepers but refused to help Lumumba suppress the secessionist provinces. At this point, Lumumba took a bold – and with hindsight fatal – step and turned to the Soviet Union for weapons, training and other military support to launch an offensive against the separatists.

There is no evidence that Lumumba had ideological sympathies with Soviet Communism, or was doing much more than trying to enlist help from the only quarter where he could find it. In any case, the practical assistance given by the Soviet Union turned out to be minimal. But the United States was not happy. This was just months after Castro’s revolution in Cuba. The worry was that the Congo might be next on the list to become a Soviet client state. A cable from the CIA station chief in the Congolese capital described what was happening as a ‘classic Communist takeover’.

The country was now dangerously split. In the secessionist areas of Katanga and South Kasai, Lumumba supporters were no longer welcome and many fled to avoid trouble. In the capital, President Kasa-Vubu was under mounting pressure from Western powers to remove Lumumba from office.

By September 1960, less than three months after Congo’s independence, Lumumba’s 81-day term as Prime Minister was over. After violence by Lumumba’s troops in Katanga, he was dismissed by President Kasa-Vubu, a move he contested. But when he fled the capital he was arrested by the recently appointed Army Chief of Staff, Colonel Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, a staunch anti-Communist who five years later, with US backing, was to take over in a bloodless coup, change the country’s name to Zaire, and become one of Africa’s longest-serving despots.

Once in captivity, Lumumba was despatched to Katanga, one of the provinces that had battled him for autonomy. When he was handed over to local forces, it was to all intents and purposes a death sentence. On the night of 18 January 1961, he was shot by firing squad and his body reportedly dissolved in acid to erase any remains. News of the execution was not made public for weeks, for fear of rousing public anger.

As well as his Congolese rivals, Britain’s MI6 and the American CIA were all thought to have been involved in the events leading up to his death, an extrajudicial killing of a democratically elected African leader who was seen to be too close to the Soviets and therefore, as so often during the Cold War, necessary to remove to stop the spread of Communism.

In the decades that followed, the Soviet Union hailed Patrice Lumumba as an anti-colonial socialist hero and martyr. They even named a university in Moscow in his honour. Elsewhere he served as an inspiration for independence causes. But in the Congo the upheaval that led to his early death halted the prospect of a peaceful transition to democracy when it had barely begun. What followed instead were decades of bloody military dictatorships and a country still ravaged by conflict today.

Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja was born in 1944 and grew up in the post-war period in what was then known as the Belgian Congo.

I was born in a Presbyterian mission station close to Laputa in the Kasai Province of the Belgian Congo. I grew up in that mission station until I was 14, when I went to another mission station for secondary school, close to the town of Luluabourg, now Kananga. We were kicked out because of inter-ethnic strife between Lulua and Baluba – actually people of the same ethnic group but divided through history. I went back to my own region and attended secondary school there for two more years.

We were extremely politicised. The struggle for independence started basically in 1956, and I went to secondary school in 1958. The missionaries gave us access to a radio, where we could listen to the BBC, Voice of America, Radio Moscow and so on, and we had all of the major newspapers published in the Congo delivered to our school. So, we were very up on what was happening, not only in the Congo but what was happening in the world. We knew, for example, what was happening in Vietnam and Laos and Cambodia. We knew about the independence of Sudan, Morocco and Tunisia in 1956, the independence of Ghana in 1957, the independence of Guinea in 1958 – so you can see why the Congo wanted to become independent like the other African countries. And, for that matter, countries in Asia which were also becoming independent. We felt that we could administer ourselves just like any other country in the world. I was extremely political – as a matter of fact, I was expelled from my secondary school in April 1960 for ‘independence activities’.

Our missionaries were American Presbyterians, almost all of them from the Southern states of the USA. They had a very arrogant attitude, very condescending – in a sense, probably racist – and they said that we Congolese could simply not rule ourselves, we were too backwards and too behind the times to be able to do that, and so we took outrage at that. So, one time there was a demonstration by students which got out of hand: some irresponsible students torched the library of the school, and somehow I was designated as one of the ringleaders, which wasn’t true. I was a participant. I didn’t participate in the burning of the library or anything like that. I was simply doing peaceful protest, but some of our comrades got out of hand. So, when the college did its evaluation of what happened, I was among the people chosen to be expelled from school.

The Belgians had set up a very good train system in the Congo, and I lived 10 kilometres away from a major railroad station, so we travelled a lot by train. The trains had four classes of cars: first, second, third and fourth. Blacks were allowed only in the fourth and the third, which were the most elementary. The fourth class had only wooden benches. The third class was a little better – they had cushions. The second and first were basically luxury cars. Those were reserved for Europeans and those Congolese who attained the status of the évolués. And, of course, when you went to the train station, blacks had to line up in a queue to buy a ticket; a white person could simply walk straight up to the counter and buy her or his ticket. So, discrimination was everywhere. I lived in a mission station where we were segregated. We lived through segregation and discrimination and oppression on a daily basis.

We didn’t like the Belgians. The Americans, we could excuse them. The Belgians, we didn’t like them at all. They were extremely rude, they were very racist. They called us macaques – monkeys. They whipped people in public: every day at 6 o’clock and 12 noon, when the Belgian flag would be raised, prisoners would be whipped publicly. Those of us walking to the train station had to witness these prisoners being whipped. We lived under a very, very harsh colonial rule.

Wung’a Lomami Onadikondo was a schoolboy in Katanga Province in the far south-east of the country.

There were schools for black people and schools for white people. I attended what was called at that time a Metropolitan school, a white school, because my father applied. There were conditions to accept children: they had to give evidence that they had the same life standards as the people who normally attended that school. They would come and visit the family of the child to see if they were living as white people were living. Then there was the medical condition to make sure you had no contagious diseases. You had to undergo a lot of medical research – blood and urine and faeces and everything. You had to pass an exam to check if you were speaking French and had the level to attend that school.

People didn’t live in the same places. There were places for white people and places – cités indigènes – for black people. I was in between. When I was attending that school, my relations with my mates where I was living were not very normal because they considered me as somebody who attended the white children’s school.

There were municipal elections in 1957, and my father went for the municipal council. My brother and me helped him to run his campaign, door to door. We knew that some change was coming. I was aware of everything which was happening, because my father’s friends used to come and listen to the radio at home and to make their comments, so I knew what was happening.

Almost all of us in secondary school were supportive of Kasa-Vubu’s advocacy of immediate independence. And, of course, when Lumumba became the pre-eminent leader of the independence movement, we supported Lumumba. Probably the great majority of our students were Lumumba supporters.

All we knew about him was through his speeches on the radio or articles in the party’s newspaper, the newspaper of his National Congolese Movement, which was one of the most popular newspapers among students. Basically, we liked the fact that he was a very advanced person in his thinking: he was for national unity, against those parties that were advocating federalism or secession and so on. We liked very much that he wanted to see an independent Congo that was unified, that was truly sovereign and that was going to use Congolese resources to benefit the people of the Congo.

Jacques Brassinne was a Brussels-based Belgian diplomat who was to become deeply involved in the process of Congo’s independence.

In 1959, we had a few problems with the Congo. We had very big troubles in January 1959, with a lot of deaths in Léopoldville. In Brussels, we decided to take the problem of the Congo seriously. It was decided that in January 1960 a big conference would be held in Brussels with African leaders and members of our government: Conférence de la Table Ronde, Conference of the Round Table. I was involved in that conference because my minister was its president. I was the only man in his cabinet who had a diploma in African political science, so I became at that time the specialist on the Congo, although I had never been there at that time.

I met all the African leaders when they came to Brussels for the conference. I was the secretary of the conference, so all of them came to me to ask questions, to pay taxis, to pay hotels, to pay expenses, so I got close to most of them.

The first time I went to the Congo was two days before independence, and I stayed at the Belgian embassy in Léopoldville for six years. I was there when King Baudouin was making his speech.

Joseph Kabasele, who was one of the leading figures in Congolese popular music, composed the song ‘Indépendance Cha Cha’ in Brussels on 27 January 1960, the day that the Round Table Conference decided that independence would take place on 30 June 1960.

I followed the ceremony of independence on the radio. King Baudouin of Belgium basically insulted us in his speech, telling us that the independence of the Congo was the culmination of the civilising mission started by King Leopold II – King Leopold, the butcher of the Congo, the man responsible for ten million Congolese lives lost during his reign. For this guy to tell us that this was our civiliser, it was simply insulting.

I knew Patrice Lumumba from before, and I was there when he delivered his speech. I saw Lumumba writing on his knees, so he adjusted his speech after hearing King Baudouin. He had a very clear voice, and we were very upset to hear what he said about the Belgians, and the way the Africans had been treated by the colonial imperialists. He was not very kind to Belgium.

The speech he delivered was to the people of the Congo, it was not directed to the people of the Assembly. He said, ‘We have been slaves, we have been put in jail, we have been hungry.’ It was really not very acceptable for the people who were present.

Kasa-Vubu made a speech but made no sense. We were very, very excited by Lumumba’s speech, which told it like it is. We loved it. We loved it because it told the truth. It was probably not very diplomatic. One of the problems we have with the Western press is that you guys never criticised King Baudouin’s speech, which was patronising and insulting to the Congolese, so it wasn’t diplomatic either. They criticised Lumumba’s speech because he wasn’t very diplomatic, but what he said was completely the truth. No one could quarrel with the facts; the facts he told were extremely correct.

At that time, we believed that Lumumba had done what he had to do, because we knew him very well and we knew the position he had taken before independence. We knew that the way he behaved was to win the election. He became Prime Minister – that was not our choice, but Belgium believed in democracy. Lumumba had a majority at the Chamber of Deputies and at the Senate. He was Prime Minister – we accepted it. We would like to have had another one, but it’s like that. So, at that time things were clear and we were not nervous at all. We said, ‘Well, we have Lumumba, we will deal with him, it’s just a matter of time, he will certainly understand that he will need us.’

Wung’a Lomami Onadikondo remembers how the festive mood after the proclamation of independence changed quickly.

It was a very big feast, a very big celebration. The independence was proclaimed on 30 June 1960. It was a Thursday. So it was a very long weekend. And the first day people had to work, there was a mutiny of the army. Before independence, the Congolese leaders were discussing with the Belgian authorities to promote some Congolese in the army because there were no Congolese officers. When independence came, the soldiers saw that everything changed in the administration but all the officers in the army were still white.

The people of the Congo followed everything on the radio. The major event that occurred was the mutiny of the armed forces, which took place only five days after independence, on 5 July. What happened was that the military were extremely displeased with the fact that we got independence and then kept the army structure exactly the same way as it was under colonialism: not a single Congolese officer. During the colonial period, the highest-ranking Congolese in the military until 1959 was sergeant-major. In 1959, some sergeant-majors were sent to Belgium for training; they became warrant officers. We didn’t have a single lieutenant or sub-lieutenant, which meant the Belgians kept control of the military.

The soldiers had made their displeasure known to Lumumba and other politicians. Lumumba took the technocratic position that, ‘Yes, we know that you need promotions but we’re going to train you first before you get officer appointments.’ Then the soldiers replied: ‘What training did you have to become Prime Minister? Your ministers – what training did they have?’ The Belgian commanding officer of the armed forces knew very well all the discontent in the armed forces because he had excellent intelligence services. So, on 5 July, he called a meeting of soldiers in Kinshasa and wrote in capital letters on a blackboard: ‘BEFORE INDEPENDENCE = AFTER INDEPENDENCE’. He said, ‘Independence is for civilians. For you, things are not going to change. Discipline will be maintained as before, under Belgian officers.’ So it was very provocative. So the soldiers went to the ammunitions depot, took up guns and ammunition, and disarmed all of the Belgian officers. They communicated to all other military camps around the country. This was the event that led to the flight of most of the Belgian civil servants, military officers, technicians, engineers and so on.

And this is what brought about the Congo Crisis. Belgium intervened on 10 July with Belgian troops stationed in the Congo and then brought in reinforcements from Belgium. And then on 11 July, the Katanga Province seceded, and this was the beginning of the real confrontation which led eventually to the assassination of Lumumba.

Mostly, people were very supportive of Lumumba. Kasa-Vubu was President – at the beginning, he sided with Lumumba. They went around the country together to pacify soldiers and to restore order. They also went to the American ambassador and asked for US intervention. The ambassador told them that the United States could not intervene – the USA, being an ally of Belgium in NATO, would never intervene against Belgium. The ambassador advised them to go to the United Nations. So they asked the United Nations, and the UN agreed to send troops to the Congo.

Through radio, we could tell what the criticism of Lumumba was in Western capitals and how badly he was seen by the Western powers. They were calling him all kinds of names: lunatic, Communist, Communist sympathiser, unstable, all kinds of stuff, which simply amazed us. We had no such conception of Lumumba, no such perception that he was that kind of person, but that’s how he was described.

Lumumba was not a Communist. He had contact with Belgian Communists when he went to Brussels, but he was not close to those kinds of ideas. He had maybe read a few books on Communism, but he was not a Communist. Some people thought that. But to be frank with you, the secret service in Belgium followed Lumumba for months and months; they knew everything about the contacts, about the kinds of people he met. If somebody can prove that he was Communist, let them say that, but they will have to prove it. What he wanted was very clear until he got it. He wanted independence for the Congo. He wanted to have all the very important ministries in his government – security service, ministry of the interior, ministry of propaganda – so he got what he wanted. But he never really formed a kind of programme. His programme during the year before 30 June was to have independence and then we’d see after. So, you won’t find any papers about what kind of policy he wanted to make.

During July, there was quite a lot of trouble all through the Congo. At that time, Lumumba had the support of the Americans, of the CIA, and also from the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Dag Hammarskjöld. Hammarskjöld really thought that the problem of the Congo was the Belgians – he thought that if you got rid of the Belgians you wouldn’t have any problem with the Congo. It was completely false. After that, Lumumba went to the United States and to the United Nations and had lots of contact, and they came to believe that Lumumba was not exactly as they thought. Then he had a lot of contact with people who were close to the USSR, like Guinea and Ghana. Those people were examples for Lumumba. He wanted to change the political system of the Congo to a kind of dictatorship. That was the development of his thinking.

I was in Léopoldville until the end of August, and we felt at that time that Lumumba was changing his mind. And then Dag Hammarskjöld changed his mind, and Eisenhower and the CIA changed their minds, saying, ‘We are going to have not a Cold War but a warm war in the Congo.’ Nobody wanted to help him apart from the Soviet Union and its allies. At that time, the Russians made a lot of promises to Lumumba, but in fact they did very few things. They promised trucks and aeroplanes and so on, but they only gave him some very old machines. I had the opportunity to speak to him, but he was not able to trust any more.

One consequence of the spiral towards anarchy was white flight, including from newly autonomous Katanga, where Wung’a Lomami Onadikondo grew up. Wung’a’s father – a Lumumba supporter – had to flee to avoid arrest. The rest of the family would follow.

Where I was living, it was on the road to Rhodesia [now Zimbabwe] and when white people began to flee to Rhodesia they were leaving only with their suitcases, they lost everything. A boy of my age I know went to see them flee and he was shot dead.

We left during the night because our neighbours were Katangese. We were friends before independence but from 11 July, when Katanga proclaimed its independence, things didn’t go well any longer. We knew there were things we had not to say because it could endanger our families, so when we left it was at three o’clock in the morning to go to the airport and then we left.

In December 1960, I was at my second secondary school, not far from the secessionist Kasai Province. I was now in an environment where the majority were anti-Lumumba. I was more or less at risk because we were identified by the principal of our school as young people who were pro-Lumumba and we were very, very scared because we had to be very careful about what we say, fearing that they might arrest us and send us to be killed.

What we knew for sure was the fact that Lumumba was dismissed as Prime Minister by Kasa-Vubu, the President, on 5 September 1960, and this dismissal was totally illegal in our view. Here was a Prime Minister in a parliamentary democracy, where he had majority control of both Houses of Parliament, the House of Representatives and the Senate. And, of course, the two Houses rejected Kasa-Vubu’s decision, saying that Lumumba was still Prime Minister. Then, on 14 September, Colonel Mobutu – who used to be Lumumba’s protégé – staged a coup d’état against Lumumba.

We knew about the main events, and we followed them: Kasa-Vubu’s dismissal of Lumumba, Mobutu’s coup d’état, and then Lumumba’s attempt to run away from Kinshasa and go to Stanleyville, and his arrest, and then his being sent to Katanga, where he was killed.

I was in Élisabethville [in Katanga] when Lumumba arrived around a quarter to five in the afternoon. He came with two other prisoners. All of the Belgian consulate was against his arrival. Lumumba gave troubles to all the rest of the Congo, and we were for the independence of Katanga, so if Lumumba came to Katanga we knew perfectly well that he would be killed. We knew that because the Minister of the Interior had said several times that if Lumumba came to Katanga he would be killed right away. He was sent there by his worst enemies: Mobutu, Kasa-Vubu, Bomboko. They were not able to keep Lumumba in jail because he had a lot of partisans, so they decided to get rid of him, and the way was to send him to Katanga. And so the problem was solved. To be frank with you, when Lumumba arrived in Élisabethville, I said to my friends from the Belgian consulate, ‘This is the end of Lumumba.’ And it was true.

We didn’t know about the killing until February. He was killed on 17 January, but the Katangese authorities kept the information secret. It was only in mid-February that they announced that Lumumba had escaped from prison and he and his two companions had been caught and killed by villagers – which was a total lie. He was killed by an execution squad of Belgian soldiers and police.

Don’t trust the people who try to see Lumumba as a prophet. He was not a prophet. He was utilised by people who wanted to make the kind of policy he had in mind.

He remained extremely popular in most of the country. Even in areas where the politicians were against him, among ordinary people he was very much admired. And, of course, Mobutu followed the popular mood in the country by naming him a national hero in 1966.

They say that he was unpredictable. That means he was not submissive.