THE BERLIN WALL epitomised the Cold War division of Europe. When it was breached in November 1989, Soviet control in Eastern Europe collapsed virtually overnight. But the simmering tensions that led to its construction had brewed more slowly.

From the outset, when East Germany was first established as a separate socialist state by Stalin in 1949, its 900-mile border with West Germany was a problem. With no physical barrier to prevent traffic between the two, it was difficult for the East German authorities to stop those citizens who chose to flee westwards. At first, the East German government did not try to stem the exodus, in part calculating that emigration would get rid of those awkward types who might hinder the building of socialism. But in 1952 ‘deserting the republic’ became a criminal offence and the main border between East and West Germany was sealed with barbed-wire fencing and watchtowers. The exception was Berlin, still ruled jointly by the four occupying powers of Britain, France, the United States and the Soviet Union, where the border remained open.

The city of Berlin was unique. Whereas the remainder of the Eastern Bloc was increasingly sealed off from the rest of Europe, Berlin remained a transit point, a Cold War gateway between Communism and capitalism. And West Berlin became an extraordinary display of Western capitalism and democracy, linked by road and rail corridors to the West, but – as the Berlin Blockade of 1948–9 had shown – also a precarious enclave, surrounded by Soviet-controlled territory. For many citizens in the East, continued access to West Berlin was a precious outlet, a means of temporarily escaping the stifling rhythm of daily life under a Communist regime and sampling Western prosperity. And for those who wanted to leave permanently, it was the one place they could still cross to the West relatively easily. Once they were safely in West Berlin, they could then transfer to West Germany, where all Germans had the automatic right to become citizens. West Germany even paid for many refugees to fly out.

As early as 1952, East Germany’s leader, Walter Ulbricht, had wanted the Berlin loophole closed. But the Soviet leadership in Moscow was reluctant to hand the West a propaganda victory. Putting up a wall to keep its citizens from escaping, it was argued, would be tantamount to admitting that Communism could not compete. So, Ulbricht was instead told to take steps to boost the East German economy and prove to both his own citizens and the West that life in a Marxist-Leninist state was a better option.

But the flood of émigrés kept streaming westwards. By 1956, over a million people had left, most of them young, well-educated professionals and skilled workers, the lifeblood of the East German economy. East Germany was in fact the only state in Europe during the 1950s to experience a net loss of population. In contrast, West Germany was economically booming and was now under a German Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, whose aim was to create a free, united Germany. For the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, the nightmare scenario was of a revived capitalist Germany, backed by the United States and armed with nuclear weapons, challenging a much weaker East German state, and ultimately posing a direct threat to the Soviet Union.

What is more, 13 years after the end of the Second World War there was still no formal German peace settlement. So, in 1958 Khrushchev tried another tactic. He warned the Western Allies that unless they signed a peace treaty recognising the existence of two German states and agreed to end the post-war occupation of Berlin and transform it into a free, demilitarised city, he would sign his own peace treaty with East Germany and turn over control of all lines of communication and access rights to the East German authorities. In essence, it was an ultimatum and a threat: either agree to withdraw, or be forced out of Berlin in any case.

It did not work. Led by President Eisenhower’s administration, the Western powers stood their ground and, as they had a decade earlier, refused to abandon West Berlin. Meanwhile, the brain drain of those opting for a new life in the West continued.

By January 1961, the authorities in East Germany and in Moscow realised that it was imperative that something be done. Between 1949 and 1961, at least 2.8 million people had left East Germany – one-sixth of the population. Not only was it causing a serious labour shortage, East Germany’s claim that socialism was superior to capitalism was beginning to ring decidedly hollow.

By now, a new American President had taken office, the young Democrat John F. Kennedy. At their Vienna summit meeting in early June 1961, Khrushchev once again demanded that the Western Allies relieve the pressure on East Germany by agreeing to withdraw from West Berlin and sign a peace treaty to recognise East Germany. But like Truman and Eisenhower before him, President Kennedy refused to cave in and the summit ended in acrimony. As the political temperature rose, both sides moved to hike their military spending.

Khrushchev decided that the only way to stop the haemorrhage was to give Ulbricht what he wanted: the green light to dust off long-laid plans and start secret preparations to build a wall around West Berlin. The plan was kept under wraps, although Ulbricht declared at a press conference in June 1961 that ‘no one has any intention of building a wall’ – a rather too vigorous denial.

The first stage of the Wall went up under cover of darkness, in the early hours of Sunday, 13 August 1961. East Berliners awoke to find East German police and army units digging trenches and unrolling bales of barbed wire to cut off their access to Berlin’s western sectors. Before long, concrete blocks were added, and eventually a 12-foot-high concrete wall was zig-zagging through the city, reinforced with steel-mesh fencing and watchtowers. Parallel to the Berlin Wall was the so-called death strip, open ground policed by armed border guards who were under orders to shoot anyone who tried to cross over. And ringing the city, a few miles outside, were Soviet troops and tanks, poised to intervene if needed. No longer was it possible to travel freely into West Berlin by train or on foot. Some East Berliners, desperate to escape, jumped from windows that faced the newly sealed-off west, or raced across the Cold War’s new no-man’s-land.

Soon, crossing from inside East Berlin became too dangerous. Some sought more indirect routes, trekking out into the East German countryside to approach West Berlin from outside the city, where there was less intense scrutiny from border guards.

Those who made it safely into West Berlin could start again, creating new lives for themselves in the West. But their freedom came at a cost. Relatives left behind in the East were now unreachable, and for the next 28 years they would be on the other side of the Iron Curtain. During that time, the Berlin Wall would stand not just as a physical barrier cutting the city in two, but as an emblem of the Cold War division of Europe.

At a political level, leaders on both sides concluded that the new status quo was hardly an ideal arrangement, but it was better than the alternative of a conflict that might go nuclear. Officially, the East German government called it the ‘Anti-Fascist Protective Wall’, constructed to protect the East German state from the aggression of Western ‘fascists’.

Khrushchev was franker. He admitted that the wall was a ‘hateful thing’, adding that ‘you can easily calculate when the East German economy would have collapsed if we hadn’t done something soon against the mass flight. There were, though, only two kinds of countermeasures: cutting off air traffic or the Wall. The former would have brought us to a serious conflict with the United States which possibly could have led to war. I could not and did not want to risk that. So the Wall was the only remaining option.’

For the Americans, the Wall was, as the US Secretary of State Dean Rusk proclaimed in 1961, a ‘monument to Communist failure’. But there was also relief that the new arrangement did not appear to jeopardise West Berlin’s access to the outside world; and while there was now a de facto partition of Berlin, it was hoped that it might ensure more international stability. In a letter to the Mayor of Berlin, Willy Brandt, written not long after the Wall went up, President Kennedy warned that he too was anxious to avoid at all costs a confrontation that might lead to war with the Soviets.

‘Grave as this matter is,’ he said, ‘there are … no steps available to us which can force a significant material change in this present situation … This brutal border closing evidently represents a basic Soviet decision which only war could reverse. Neither you nor we, nor any of our Allies, have ever supposed that we should go to war on this point.’

Nonetheless, the building of the Berlin Wall did ramp up friction between East and West. Western garrisons in West Berlin were reinforced, as were Soviet troops on the other side of the border. In October 1961 an incident at the Berlin crossing point of Checkpoint Charlie led to a stand-off between Soviet and American troops. For 16 hours their tanks faced each other on full alert before both sides backed down and a confrontation was avoided.

Leslie Colitt was an American student who went to West Berlin in 1959 to see for himself what this Cold War gateway between Communism and capitalism looked like.

One could sense that it was a divided city, politically, but in human terms it wasn’t … People flowed back and forth between East and West Berlin. I had the feeling that it was still one city – which politically was divided, but it didn’t really matter much in terms of people being able to meet and get together, families and all that sort of thing.

The atmosphere in East Berlin was very raw. In the streets, there were more holes between the buildings than there were buildings: so much had been demolished during the war that the sight of a whole building was quite something. People would come over from the East to buy almost everything in the West that they could afford.

They had to exchange money at the rate of four East marks for one West mark. So that means that things were four times as expensive […] They came over to buy fabrics. The women would buy textiles to make up into dresses in the East. Mechanical things, tools, all kinds of things like that they would buy in the West. Things for their car and women cosmetics, cosmetics, cosmetics. There was nothing like that in the East. Stockings … You just name it, and they would buy it, if they had the money.

In the student village where I lived in West Berlin, about 20 per cent of the students living there were from East Germany. And because they came from families which were considered bourgeois, they couldn’t study in the East, or at least not the subjects they wanted, so they came to the Free University of Berlin or the Technical University in West Berlin.

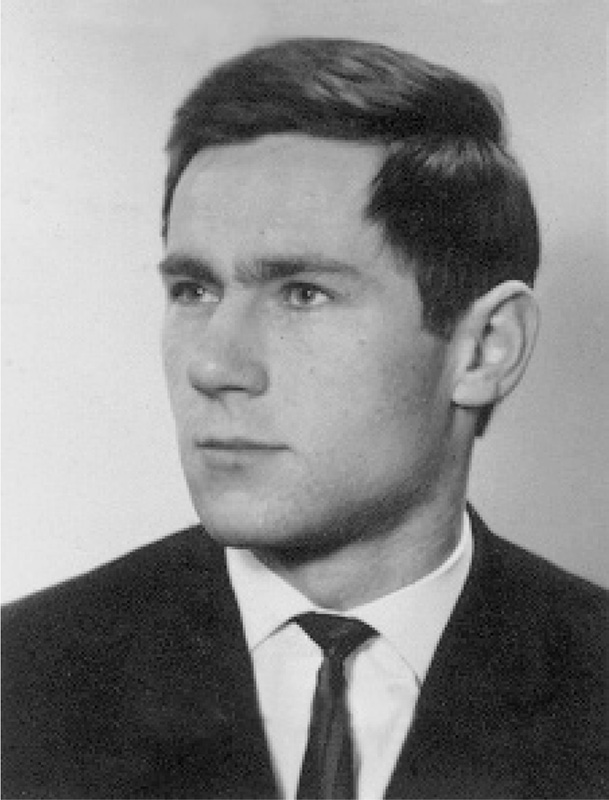

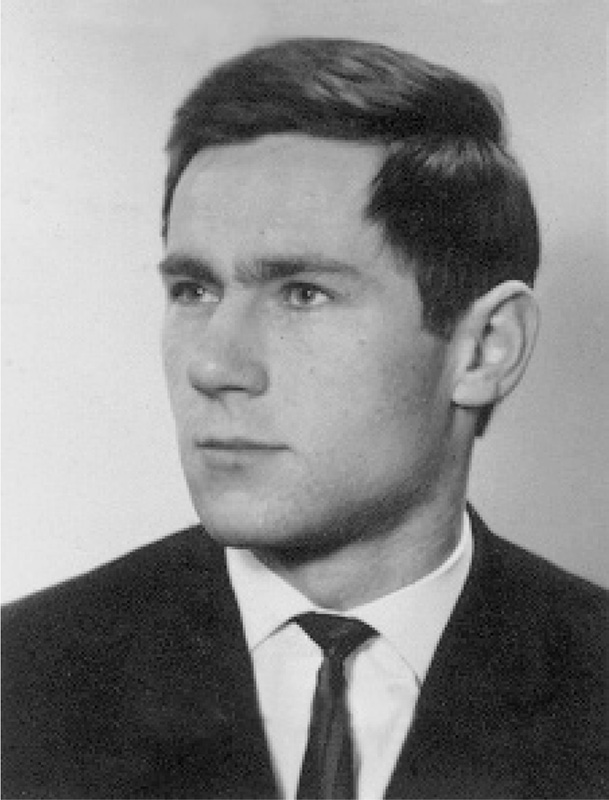

On the other side of the city, Joachim Rudolph was a young East Berliner who had taken part in the uprising against the Communist government in 1953. For him, the saving grace of life in the austere, stifling East was that Western prosperity was just a metro ride away.

We went to the Kurfürstendamm and looked at the great cars which stood on the streets and photographed them. My friends were into cars. And then they developed the photos in a big bathtub. We very often went to West Berlin, and two of my closest friends were already studying there. We had done A levels together, we knew each other well, and we completely trusted each other.

I knew people who fled; I even helped one family, our neighbours, to flee. I helped them carry things over the border because the borders were not controlled and, if one didn’t carry suitcases that were too big, one could walk past the policemen at the border on the East side.

The numbers of refugees from East to West Berlin rose and fell. But in July and August of 1961, the numbers rose again, and there was an enormous shortage of workers in the East. It was said that the GDR wouldn’t put up with it for much longer, especially because it was mostly young people who had a good education that went to the West and did not come back.

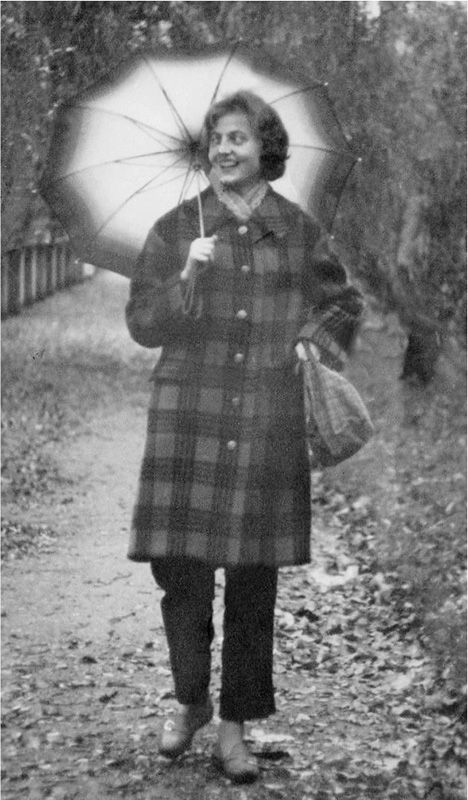

In 1960 Gisela Nicolaisen was a student in Leipzig; she watched as, day by day, people eerily vanished around her in her hometown of Weissenfels, south-west of the city.

Suddenly a couple would be gone, or a whole family, or the GP, or the boyfriend of my sister, or a former classmate … Rumours would spread very quickly through the town, and one knew that they weren’t there any more. I was happy that they managed to do that. And I started to ponder: ‘Should I not go myself? Is it still possible? How long is it still possible? When will they shut the door? Then I won’t be able to leave at all.’

But there was also a case of a music teacher who suddenly wasn’t there any more, and that was very much condemned as a betrayal of the state. She came back, though, because she couldn’t make her way in the Federal Republic. She was welcomed with open arms and given money so she could find her feet again.

One had to apply for a place to study and one had to answer a lot of questions, and the study places were then allocated. That was determined by your background, depending on whether you were a worker’s child or a farmer’s child or a child of the intelligentsia. Workers’ and farmers’ children were given preference, and they could basically choose to study whatever they wanted, especially from professions that were traditionally occupied by intellectuals, such as doctor, pharmacist, lawyer or judge. Those positions would not be given to children of intellectuals.

In addition to your school record, there was your social-political work – how you had applied yourself to the building of socialism, whether you held a position in the Free German Youth [Freie Deutsche Jugend (FDJ)] and so on, and whether you had any family who had already fled the GDR. I was the child of an ordinary employee and I had fairly good marks, but I couldn’t show much social-political work, and I also had a sister who had left the GDR four years earlier and now lived in Switzerland, so I had very bad prospects. I applied to study pharmacy and food chemistry and, of course, I did not get a place; if I wanted to wait for them, I would have to have proved myself by working for two years in production, or I could have studied to become a teacher of maths and chemistry. At first, I rejected that because I never wanted to become a teacher in the GDR, because it was a highly politicised profession. But my father told me it was the only opportunity to actually get to university so I should take it – and who knew what might be done with it later. That convinced me, so I accepted the offer and went to university in Leipzig.

For the duration of my two years’ studying, I could not assess how my fellow students were politically oriented – except for those who wore the party badge, of whom there were quite a few. They never expressed themselves privately. We always spoke in party jargon in front of the teachers, at political gatherings and in front of those with party badges. So, for two whole years, I could not find out who thought as I did, who was critical of the regime. That situation was very depressing.

Pretty soon, our seminar group was declared a socialist collective. This meant that we not only studied together but also learned together in the remaining time, that we drank beer together, that we went to the theatre together, that, at the weekends, we went on outings together. It was a controlling measure. A private life was not desirable.

One day, the Free German Youth secretary came to us and ordered us to call in pairs on those farmers who had not yet consented to join the state cooperative farms. I was on the side of the farmer who refused to give his farmyard to the cooperative, but had to lecture him that he should join it. The farmer was so pale and so unfriendly. As soon as he said, ‘No’, I got up and left. My fellow student didn’t say anything. It was an excruciating situation. But I was always afraid that if I opposed all this – if I said anything against it – I would be summoned and interrogated. That’s what I was most afraid of because I didn’t know if I would be able to stand my ground. Out of that fear I did what was expected of me. And inside, I was always torn.

When I was 18, I hadn’t felt able to leave home by myself, forever, because if one went one couldn’t return. I knew already that I wanted to live and work in a Western country, but it was simply too early. So, when I started university I was struggling with what would be the right decision: to leave or to stay. That is something that my father got out of me.

He came into the hallway and said: ‘Do you really want to go? Do you really want to go?’

‘Yes, I really want to go!’

‘Then go now.’

That was like a kick. It was like a liberation. And then the decision was made.

We had to ensure total secrecy. No one was to hear of it. We played out every situation I could run into on the way to Berlin. We drafted carefully phrased letters, which I would then send from Berlin, to the university, to my seminar group – and to my parents, who officially would not know anything about it. We thought of everything so that no one could prove that they knew of it; that would have been a criminal offence. They also wanted to be on holiday when I left, so that it looked like I had used their absence to secretly head to Berlin.

I had asked at West German universities whether I could continue my studies there and they said yes, if I could prove my previous studies with the relevant course material. I couldn’t have any course material in my suitcase – that would have been very suspicious. So, we took photos of my course material, and hid the negatives in the spines of books, which I then sent to my sister in Switzerland.

Gisela eventually headed West on 5 November 1960.

It was a Saturday and, like every Saturday, I went to the train station. Usually, I would be going home, but this time I was going in a different direction. You can plan as much as you like, but there are still some situations that you can’t calculate in advance. I bumped into a fellow student at the station, and I had to get rid of her because I wasn’t buying a ticket home but to Berlin – under no circumstances could she be allowed to hear that. I remember that I was not nervous at all. I thought completely clearly about what I could do to get rid of her. I told her to stand in line in the other queue and we’d see whose turn it was first. That’s what she did, and she could not hear what ticket I bought. I then sat on my train and between my platform and hers there was another train that was waiting to leave. My train left first, so she would not have been able to see me board.

I was very lucky at the border control. A group of young nurses had got on and taken over the whole compartment. They were in high spirits and, when the guard came in to inspect passports, they started to flirt and joke with him. He came to me, and I also smiled at him. He looked at my passport, turned around, made a few more jokes with the others and left. And that was it.

I had been to West Berlin before, and I knew my way around. I knew what to say at the ticket booth – that one had to buy a return ticket – and I moved confidently through the stations. I think that was an advantage because there were hundreds who went that way every day. If I could move like a local, I wouldn’t stand out so I would not be noticed. I sat close to the door, the train stopped, I got off and then I was on Western ground. It had happened.

We never said that I had left for political reasons; that would have made things very difficult for my parents. We said that I had fallen in love with one of my pen pals and had gone to join him in West Germany. That was believed because my fellow students knew that I had a pen friend. And my parents got off lightly. They suffered no real reprisals. When I met my former fellow students almost 40 years later, they all believed that I had married that pen friend.

Leaving is a decision that I have never regretted. It was the best decision in my life.

Soon it would be much more difficult to flee through East Berlin. On 13 August 1961, Leslie Colitt awoke to the news that East German soldiers were enclosing West Berlin in barbed wire, backed up by Soviet tanks in case of trouble.

When the refugee crisis reached its peak, something like two to three thousand people were coming over every day from East Germany or East Berlin. And one knew, something had to be done […] We thought, if the East would do something radical, like trying to seal off the city, that the Western powers, the US, Britain, France, would react in some strong way, militarily or so, but of course, that never happened.

I was away on a vacation with my parents in southern France on 13 August. In the morning, we heard the radio and the main news item was that a wall was going up in Berlin. Partition. Partitioning of Berlin.

I immediately sent a cable to my fiancée in East Berlin saying I would be arriving as soon as I could get there and that we should meet outside the Pressecafé in the Friedrichstrasse.

And the first thing we discussed, of course, was how she was going to get out of East Berlin, which was no easy matter because the Eastern sector had been severed physically from the West for the first time.

One went through all the possibilities. Friends who might know somebody, who could smuggle her out, that was too dangerous. I knew some Americans who claimed they might be able to help, but in the actual event, they couldn’t, or didn’t want to.

So, in the end, we were left with our own resources and the thing that came to mind first was my sister. She was much younger than my fiancée but nonetheless her passport would have to serve. I immediately cabled my parents to send that passport to me as quickly as they could. Four days later, I got it. With that in hand, I realised, my God, it doesn’t have an entry stamp from West Germany. That means if a controller from the East looks at it, he would wonder – how did she get to East Germany in the first place?

This was just one of these things one had to go with.

And I smuggled the passport in under my clothing into East Berlin. My sister had brown hair and my fiancée was blonde, so she had to dye her hair in order to fit the picture.

We set a date when we would have to do this because we were afraid that the controls would stop being so lax. At any date they coloured slips together with the passport with a stamp on them that would render our passport useless.

Joachim Rudolph was also away from Berlin when he heard the news.

We were on a camping site by the Baltic Sea. And there we learned via the loudspeakers that the borders were closed in Berlin. Not only that, but they also played heroic marching music all day, alongside announcements: how, at last, the German Democratic Republic could build up socialism without obstruction from evil agents and West German and American saboteurs.

We thought they were making a fuss to try to boost socialist morale. Nobody believed that the border closure could last for long. We thought that it might be like the uprising on 17 June 1953, when the borders were closed for a week or ten days and then they were reopened again and everything continued as before.

After a few days, those who were studying in West Berlin began to worry that they’d not be able to continue their courses. So, we decided to return to Berlin and see what was happening.

It was dark when we arrived back in Berlin, and we drove straight to the border at Bernauer Strasse. Now, instead of the two border policemen who usually stood there controlling the pedestrian traffic, there were five or six soldiers, with steel helmets on their heads and Kalashnikovs around their necks, guarding the border. As our car drew closer, they called from a distance that we should go back at once; we had no business being there, and we were to leave the border area.

Now we realised that the situation was serious. We met up every evening in the pub and discussed what we were going to do. And what did we want to do? We needed to be back in Dresden on 1 September to continue our studies. One friend of mine had already intended to leave at the end of 1961 or early 1962 to go to West Berlin and stay there because his father was already there. He said if he succeeded in escaping to West Berlin, then he would try to fetch his mother and his brother over too. And that was also going round in my head.

Those who lived in the GDR or East Berlin but worked or studied in the West now had to be registered, so we went along with my friends who had to do this. They came out and told us that they could not continue their studies in the West; starting the next day, they had to present themselves at a construction company on the outskirts of Berlin.

I returned to university in Dresden. There, we now had to agree in writing to be on standby to join the People’s Army for an unknown duration. We also had to bind ourselves in writing to wear the blue Free German Youth shirt to all seminars and training courses until a peace treaty between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union was signed – and I knew that there would never be a peace treaty on Soviet terms.

I went to the enrolment office and asked to be allowed to leave, and then I returned to East Berlin, because I wanted to be with my friends to discuss how we would proceed.

After two or three sleepless nights in East Berlin, I was ready. When we met up again, I said to my friend: ‘We are going to do it together. We find an escape route, and we will try to get to West Berlin.’

We got on our bikes and, beginning in the south of Berlin, we rode along the border. We tried to get as close to the border as possible to see how it was secured. We often heard and saw on Western broadcasts that there were people who had tried to flee by swimming across the River Spree. We thought that could work. But then we tried swimming at night on the outskirts of the city and immediately broke it off because it seemed far too dangerous. It was great weather, a starlit night, but we knew by then that the border soldiers had a duty to prevent the escape. We knew that on 20 August 1961 the first refugee who tried to swim from East to West was shot. He was killed.

Leslie Colitt’s plans were further advanced, but when the day came it wasn’t quite as straightforward as he had hoped. Moving his fiancée’s luggage across the East–West Berlin border involved complicated subterfuge – and began to bring him unwelcome attention.

I went over to West Berlin, then back to East Berlin and at that point in Friedrichstrasse Station, the controller looked up at me and said, ‘Didn’t I see you here once before?’

‘Yes, I was here earlier.’

‘Aha! – what are you doing here?’

Well, I had to think of some reason quickly and I said: ‘My father’s due on the train from Leipzig.’

This happened to be at the time of the Leipzig Fair, when Westerners were able to go into East Germany freely. I wasn’t sure if the controller believed me, so I decided not to use that station on our way to West Berlin.

I had agreed to meet my fiancée at the Pressecafé, which was just across the street of the station. And to my horror, my fiancée had not gotten her hair dyed at all, because all the hairdressers in her area had been closed and therefore she had tried to get an appointment at the Friedrichstrasse Station hairdresser, which she did.

There was only one thing that we had overlooked. She didn’t speak a word of English! We each had a double vodka in front of us and I was trying to give her a snap English lesson on the questions I thought she might be asked.

Had we known all this we would never have done the preparation in the Pressecafé because it was teaming with informers for the Stasi. The place was known as a meeting point for potential escapees.

We didn’t know this, so we left the café and walked up Friedrichstrasse towards what would become known as Checkpoint Charlie, the crossing point to West Berlin. It was dusk, and I could just make out the figure of a uniformed East German, standing there, alone – I will never forget the last steps up to him. We stood right in front of this very young man, and we took out our passports; I took out mine and my fiancée took out my sister’s passport and at that moment she fumbled and the passport fell to the ground. And we all dived down to the ground to pick up the passport. All at the same time. We virtually knocked heads and we laughed actually and the border guard laughed too.

I knew at that point that we were safe.

Joachim Rudolph and his friend were still looking for a safe escape route.

We had three. Two fell through because those areas of the border had been reinforced.

The third involved cycling from East Berlin into the GDR, very close to the border until we were out of sight of the border guards. Then we turned and cycled back in the direction of West Berlin into an area called Schildow. We found warning signs: ‘Border area. Keep out!’

We ignored them and carried on until we reached a field, which sloped then rose again on the other side. Our map showed that the border was at this lowest point, a small river.

On the other side we could see tractors, and my friend identified them as West German tractors – not GDR or Soviet ones. That seemed to be our ideal escape route.

Then we waited for bad weather. On the evening of 28 September, we finally saw clouds gathering.

We went home and fetched the things we wanted to take on our escape: a plastic bag with our important papers, A-level certificates, skilled worker’s certificate, birth certificate and so on, and clothes in a small briefcase.

At around eleven o’clock we were at the edge of the field, and by three o’clock in the morning we were at the river. It was 150 to 200 metres at most, but we needed four hours to cover it because we took turns to crawl. One of us crawled 10 to 15 metres, then the other followed, then the first worked his way forward. We reached the river and until then we had not seen any more indications of the border. But the map showed it. We were surprised: there was no barbed wire fence, no signs, nothing at all. We thought the border must be 50 or 100 metres after that, at the most, so we would have to cross the river.

As we dipped our feet into the river, there was a loud noise. We thought at first it was an explosion or a machine gun, but it soon turned out it was only a flock of wild geese we had startled, which had spent the night at the riverbank. They rose up and you can imagine to our ears the flapping of the wings made a terrible din. We both got a terrible fright and thought: ‘What do we do now?’ But it was clear that going back would be pointless – it would take too long, and a patrol of border soldiers might come to see what had disturbed these wild geese. We realised we just had to go on. And that’s what we did.

The river was not deep, about knee-deep, but the bottom was a bit boggy, so we had to be very careful that we did not fall down or get our papers wet. On the other side, we ran, half-crouched, to get out of sight of the river.

It was still dark, and we couldn’t see further than 15 or 20 metres. We continued running in the direction of the tractors we had seen. By then it was morning, four o’clock. When we saw the first houses, we had still not seen any signposts. We thought, ‘Are we in East Berlin? Are we in West Berlin?’

There was a blue-lit window – it was a fire station. Behind it, there sat a young man. He had his head propped up in his hands. He was dozing. We knocked. He started and said, ‘Boys, where do you come from?’

Well, where did we come from? We did not know. Were we in East Berlin, were we in West Berlin? We could only stammer.

‘Yes, yes, boys,’ he said. ‘I can imagine where you come from. Congratulations! You managed it! You’re in West Berlin.’

Joachim had made it. He went to a West Berlin camp set up to screen refugees and weed out Stasi spies, and at the end of 1961 he was able to resume his studies. Leslie Colitt’s fiancée had left her entire family. Now they were almost unreachable, on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

She immediately sent a telegram to East Berlin, to her parents, informing them that she had come to West Berlin. So, if the authorities had asked what happened to their daughter, they could say, ‘We had no idea she was going to escape.’ We only learned in 1994 that her father was demoted at work because of her escape. She didn’t see her mother for five years after that.

In those days, West Berliners who wanted to see relatives in the East had only one way of doing this, and that was to stand at a vantage point in West Berlin where they could be seen by their relatives in the East. They could wave to each other. My fiancée saw her parents only as tiny little dots about 500 metres away.