THE CONFRONTATION KNOWN as the Cuban Missile Crisis, and in Russia as the Caribbean Crisis, took place over 13 days in October 1962. It was the closest the United States and the Soviet Union came during the Cold War to triggering nuclear apocalypse.

The starting point went back to more than three years earlier and the moment, in January 1959, when a band of rebels on the Caribbean island of Cuba, led by the young revolutionaries Fidel Castro, his brother Raúl and Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, succeeded in ousting the unpopular, corrupt dictatorship of Colonel Fulgencio Batista, following a two-year guerrilla campaign.

To begin with, Fidel Castro’s new Cuban government was more nationalist than socialist, and his revolution attracted little attention in Moscow. But when he nationalised American companies in Cuba and the United States retaliated with a trade blockade, Castro appealed to the Soviet Union to come to Cuba’s aid by buying up the sugar, which accounted for 80 per cent of the island’s exports.

For Moscow, Castro’s Cuba was a welcome new revolutionary ally, sympathetic to Marxist doctrine, ready to defy Washington, and whose geo-strategic position only 100 miles off the American mainland was interesting, to say the least.

To Castro, the Soviet Union was the obvious ideological partner and a necessary source of economic support, whereas the Americans were hostile imperialists, working hand-in-glove with Cuban exiles intent on destroying the revolution.

To the United States, Castro had turned Cuba into a Communist threat and given Moscow a foothold in America’s backyard. It raised questions about the future viability of the US naval base on the island, at Guantanamo Bay. The US government decided it had to act.

In January 1961 the incoming American President, John F. Kennedy, inherited from his predecessor, Dwight Eisenhower, a plan to invade Cuba and topple Castro using CIA-trained Cuban exiles – what became known as the Bay of Pigs Invasion. But when the operation took place, on 15 April 1961, it was a fiasco. Instead of being welcomed by locals as liberators, when the exiles landed at Playa Girón and other beaches on the Bay of Pigs in Cuba, they were attacked and outnumbered by Castro’s troops and tanks. Within three days they had surrendered. It was an embarrassing failure for the Americans and a humiliation for President Kennedy.

In Cuba, it turned Castro into a national hero. But the invasion was also seen as a warning of what the United States might try again. It encouraged Castro to cement his relations with the Soviet Union, and publicly declare his allegiance to Communism and to the Soviet bloc. He also asked Moscow for weapons to protect the island against any new American attack.

The Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, was receptive to the request. He was acutely aware that American nuclear warheads were stationed in the United Kingdom, Italy and Turkey, all capable of reaching Soviet targets. Khrushchev reckoned he could offset this by placing missiles on Cuba where they could reach Washington, thereby giving the Americans a taste of their own medicine and deterring them from trying to intervene either in Cuba again or elsewhere in the Caribbean. As Khrushchev colourfully put it in discussion with his advisers in April 1962: ‘Why not throw a hedgehog at Uncle Sam’s pants?’

At first, the Americans accepted Soviet assurances that the weapons being shipped to Cuba were anti-aircraft defensive missiles, and looked the other way. But in mid-October 1962, American spy planes seemed to show evidence that missile sites were being constructed in Cuba for offensive nuclear weapons, capable of striking the United States.

The Kennedy administration went into crisis mode. The stakes could not have been higher. This was no longer a quarrel with the Soviets about Europe or a fight against Communists in Asia; it was not even long-range Soviet missiles stationed on the other side of the world; it was short- and medium-range ballistic missiles targeting US cities, being secretly installed on America’s very doorstep.

For the next few days, top security officials in the White House weighed up how to respond. A surgical strike on Cuba to take out the missiles and a bigger air offensive were both considered but discarded as too dangerous. Eventually, President Kennedy chose a less risky option and ordered a naval blockade to seal off Cuba by sea. As a precautionary measure, he also put all American military forces worldwide on a heightened state of nuclear alert, ordering all airborne strategic bombers to be armed with nuclear weapons.

Then, on the evening of 21 October, Kennedy went on television to give a nationwide address and put the Soviet Union on notice, grimly stating that the United States would regard ‘any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States’.

In Moscow, Khrushchev feared that a new American invasion of Cuba was imminent and gave the Soviet commander on Cuba permission to fire tactical nuclear weapons if the Americans attacked. He also sent a message to President Kennedy warning that, while the Soviet Union would not strike first, if the naval blockade meant any Soviet ships were stopped, the American vessels involved would be sunk by Soviet submarines. It looked as though both sides were preparing to go to the wire.

Over the next few days, tensions remained at a level that was unprecedented. The Americans held high-level meetings to talk through a possible invasion of Cuba to destroy the missiles, and concluded that it would lead to catastrophic casualties.

Meanwhile, on Cuba itself, Castro was battening down the hatches. People were told to brace themselves for an invasion. He appealed to Moscow to get ready to respond with a nuclear strike if American troops landed, and ordered his own troops to open fire on any American planes seen flying over the island.

After days of intense shuttle diplomacy to come up with a deal, both leaders stepped back from the brink. On 28 October 1962 Khrushchev announced that he was giving the order to dismantle and withdraw Soviet missiles from Cuba. Kennedy announced that he was standing down the naval blockade and confirmed a pledge not to invade the island. He also privately agreed to a Soviet request to withdraw the US nuclear missiles based in Turkey, so long as this part of the deal was kept secret. They were quietly removed the following year.

Castro flew into a rage when he learned that a deal had been done behind his back, and argued that it was a mistake to have caved in under American pressure and left Cuba defenceless. He laid out five points of additional guarantees he wanted from the United States to back up its pledge not to invade, including that it end its embargo, all ‘subversive activities’ and ‘pirate attacks’ against Cuba, stop violating Cuban air space and territorial waters, and return Guantanamo Bay Naval Base to Cuba. His demands fell on deaf ears and, under Soviet pressure, Castro had no choice but to consent to the missiles being withdrawn.

In Washington and Moscow, the outcome was portrayed as a victory. President Kennedy had stood his ground and got the Soviet missiles out of Cuba. Nikita Khrushchev had secured a promise that there would be no American invasion of Castro’s Cuba, and no American missiles in Turkey.

But above all the crisis had been a moment when nuclear madness nearly descended, but mercifully was averted. It had shown how easy it would be to trigger an all-out nuclear war, which might destroy humankind. It prompted the setting up of a teletype hotline between Washington and Moscow, and the rapid conclusion of a treaty banning all but underground nuclear tests, because both sides now recognised in their guts that avoiding nuclear holocaust served everyone’s interests.

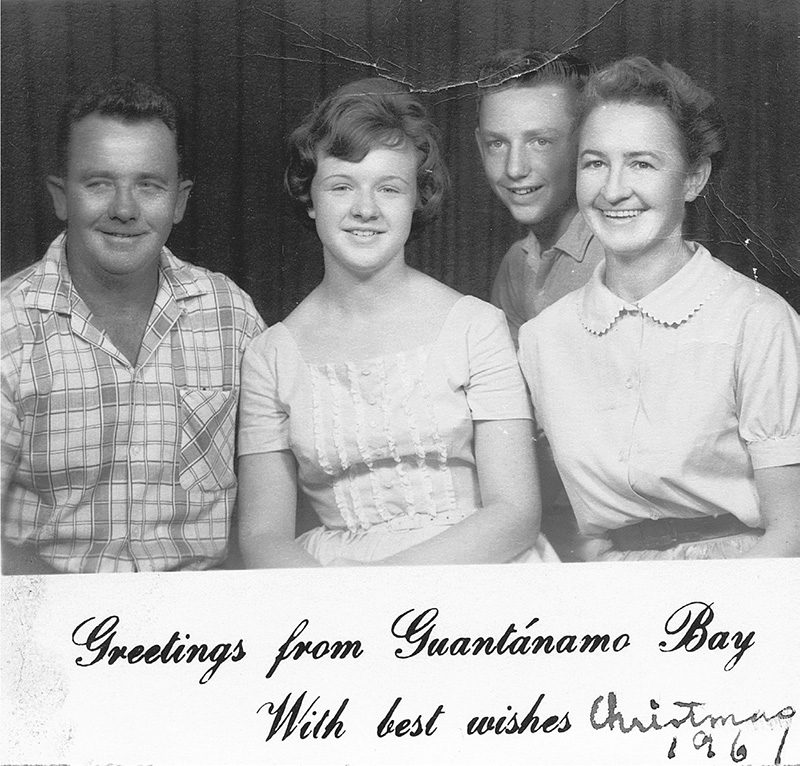

American-born Frances Glasspoole was 14 years old when she and her family went to live at Guantanamo Bay.

My father was in the navy, and he was transferred there to work, and my family went to the base, as military dependents do. We drove across the United States from southern California in our car to Norfolk, Virginia. It was the early part of 1960 – Eisenhower was still President – and when I was in Virginia, never having been to the East Coast or the South before in my life, it was the first time I ever saw ‘whites-only’ drinking fountains and bathrooms and separate sections in restaurants for what were called ‘coloured’ people at the time. It was still segregation, and the civil rights movement had not yet begun.

We flew to Guantanamo Bay on a military plane. It was green and mountainous and the water below was turquoise, and it was just different than anywhere I’d ever been before. It was both different and the same. We lived in a housing area that was not near the main part of the base; it was closer to the fence line. You could actually see the fence line from our back porch with binoculars. I rode a military bus to go to school – everywhere we went on the base, we went on big, grey military buses.

The writer Ciro Bianchi was a teenager living in the Cuban capital at the time of the crisis.

I was born in Havana in October 1948. My father was a construction worker and my mother was a housewife, so it was a typical working family. Thanks to my parents’ sacrifice we were able to study so, despite the hardship, it was a happy upbringing. Life was intense during that period [of the missile crisis] – we lived two days in one. We could have been wiped out, or God knows how many thousands of people could have died. But there was no fear. There is a scene in the film Memories of Underdevelopment in which the main character says, ‘In this country, before opening the newspaper you have to take an aspirin.’ Because the situation was really very tense, with the breaking of relationships, all kind of aggressions, even physical aggressions, and there were comrades who died in plots in Cuba and outside Cuba. It was a relentless war against Cuba and a blockade that cost us millions. So, when you see all of that, you say: ‘This is people who sympathise with Fidel and Raúl.’ We had to have a great trust in Fidel and Raúl to be able to endure all that.

When we arrived, it was shortly after the revolution. Prior to that, the gates were open and there was free travel into what we called Cuba-proper. When my family went there, the gates were closed. There was no travel. We called the land on the other side of the fence Castro’s Cuba. We were on United States land. There were thousands of Cuban nationals working and living on the base. Some of them were exiles and could not go back home for fear of execution. Some of them commuted freely back and forth every day. There was a United States gate with Marines on duty, and just beyond that was a Cuban gate, and they had set up some kind of financial arrangements for the Cuban workers to change their American dollars into Cuban pesos because American money was worthless in Cuba.

My experience with Cuban people was widely varied. Almost all the military families on the base had Cuban gardeners or maids, so we had Cuban people in our home. We made friends with them, we had social activities with them – I actually had a Cuban boyfriend.

A word that comes to mind about Guantanamo Bay in the early 1960s is that it was ambiguous. On the one hand, it was a simplistic life where everything we needed or wanted was made available to us. The lettuce wasn’t very fresh, but we had a good life. And yet not very far away there was so much else going on. One of the beaches that we went to was right on the boundary of the base, and you could clearly see Cuban militia on the other side of the fence watching us with binoculars while we were watching them with binoculars.

I think we were pretty well indoctrinated that Castro was bad and Communism was bad and Russia was a threat – I think that came with the territory of being a US citizen. Before we ever left the country, we had a mindset already in place. Living on the base, we did not have a sense of what was going on in the world. Our news was filtered. The base newspaper was a little typewritten newsletter. It talked about American politics a little bit, but we were sheltered in that way. We did not know what was going on beyond our daily lives. There was a radio station on the base and a television station on the base. That was … censored is the only word I can come up with. The television station didn’t come on until 7pm, and it was just old re-runs of The Ed Sullivan Show and I Love Lucy and things from several years previous. There wasn’t any current information. The radio station played music. I had a portable radio as a teenager, and I remember sitting outside in the backyard at night and dialling around and picking up some rock-and-roll music from the US, because we really didn’t have a lot of access to contemporary music.

There were what we called ‘war games’ every month or two on the weekends. We civilians had to stay home, and then there were tanks and noisy things going on – they did practices with aircraft and helicopters and artillery. If we did have to go out, we were stopped by roadblocks.

In April of 1961, there were increased war games going on but, because that was a standard activity on the base, it was not perceived by those of us who lived there, the civilian people, as anything different than usual. It was only later that we found out that that was in fact the Bay of Pigs. The Cuban people who we knew told us that things were really bad in Cuba and that there had been fighting and that Castro had won, but we had no idea what that was about. We were not insiders at all.

We lived under the threat of American aggression. They had invaded us in Girón already; the bombing in Havana just before Girón had happened. Before that, we suffered aggression from Trujillo, the Dominican dictator. And there were counter-revolutionary gangs that were very powerful. But we also faced the cut of the sugar quota by the United States, that was basic for the Cuban economy. We lived through the break-up of relations with the United States, the break-up of relations with the Latin-American countries except Mexico – that was the only country that never broke relations with Cuba. So all that was forming you, it was making you stronger; also the speeches of Fidel and other leaders of the revolution, especially Fidel’s, were constant and that was very instructive.

I was very involved, not in the military, but in student organisations. We performed guard duties in our neighbourhood, in the junior high school where I was studying at the time – we did all that. People had a strong conviction and great fervour, and I don’t think it was because we thought that the Soviet Union was going to help us, but that we trusted the direction of the revolution, especially the leader of the revolution: Fidel Castro.

Cuba was being threatened with an American invasion, the Soviets offered to help with conventional weapons and nuclear weapons, and Cuba as a sovereign country had the right to have those nuclear weapons. That’s the way we saw it.

Nikita Khrushchev’s son, Sergei Khrushchev, recalls that this attitude of Cuban defiance was much admired in the Soviet Union.

They became heroes to most of the Soviets, of the youth, who never knew about Cuba before but now they saw these young people fighting against American imperialism.

I remember the tension of the days, but you have to remember – what was the crisis? Khrushchev changed the major foreign policy of the Soviet Union. Stalin accepted the American and Churchill deal: ‘You must be kept in your borders. We agree that you will dominate Eastern Europe; the rest is the Western world – it’s our world. Don’t even put your nose in the Middle East.’ But my father said: ‘No. I want to be a world power. I want to be respected as an equal.’ And Americans don’t respect anybody as equal. It was not about the balance of power. It was not about infiltration in the Western hemisphere. Americans pushed Castro from them; Castro visited Washington in April 1959, and the President didn’t want to meet with him. And it was a rule of the Cold War that if you can do something bad to your enemy, do it. So, we supported Cuba, but we didn’t want to bring them too close.

I asked my father, ‘Why not invite Cuba to the Warsaw Pact?’ He told me, ‘They’re too far, we don’t know them too well, and if America will attack them we will have to start nuclear war.’ It was too dangerous, and he didn’t know what Castro would do. After the Bay of Pigs, Castro officially declared that he had joined the Soviet bloc. He told Khrushchev that he had to defend him because the obligation was for the superpower to defend all their allies, good or bad. So, Cuba became to the Soviet Union the same as West Berlin to the United States: small, useless piece of land, deep inside hostile territory, but if you will not defend it, even risking nuclear war, you will lose your face as a superpower.

So, my father decided what he could do. He cannot defend Cuba diplomatically. He cannot use conventional forces because Americans control all communications. So – send there these weapons to show America we’re serious.

But Americans are very different. We lived all the time here with enemies on the gates, you in Great Britain, we in Russia. Americans were surrounded by two oceans, they were protected. They were like the strongest predator in the world, like a tiger, but a tiger which grew up in a zoo, and when sent into the jungle they were afraid of everything. So, when they found that it is the missiles in Cuba, the American public started panicking. It was an American psychological crisis: ‘If it will be ready, they will launch against us.’ It was no logic in this – why not launch them from Siberia? It was only 20 minutes’ difference in the delivery. But it was clear to the politicians, and it was creating this panic in the United States: ‘We have to remove them at any expense.’

It made the resolution of the crisis very difficult for Khrushchev and Kennedy, and we are lucky that all of them were balanced politicians who decided not to shoot. It was very different because we knew that it was so dangerous, but for the Americans it was unique. Now they found: ‘We’re also vulnerable. We can be killed.’ In the Berlin crisis, if we start a nuclear war, Russia will kill Europeans – Germans, British, French – and Americans will watch it on TV. Now, they saw that they were the same.

I have very vivid memories of the October Crisis – we’ve always referred to this as the October Crisis. It’s too important and too dramatic to be forgotten easily. But my most vivid memory is – maybe because of our optimism and confidence in the revolution – the tranquillity with which the Cuban people faced the event. I don’t remember that there was fear, despite how terrible it was.

It was a Monday, and the weekend before had been one of those military exercise war-games weekends, or at least so we thought. There was increased military activity, except this time there were jets, and that was different. It seemed like there was a larger volume of military. But other than that, we had no clue what was going on, no idea.

I remember a headline in the Revolution newspaper. It read: ‘The nation has awakened on a war standing.’ I remember the atmosphere in Havana, I remember the militias on the streets … I remember trenches at the Hotel Nacional that are still there, because that hotel was built over a system of caves. So they took advantage of the caves to build trenches, preparing for nuclear aggression. They are still there, a tourist attraction. I also remember anti-aircraft weapons around the FOCSA Building, an emblematic building in Havana. So, there was that atmosphere on the streets of Havana: people ready with nursing posts to take care of the injured, people ready to provide food to the population – everybody had a mission. As El Che said, those days were luminous and sad.

It was business as usual, except on that particular day there was a PA announcement; the principal came on and said that we were supposed to go home: don’t ask any questions, just get on the buses and go home, and there would be further instructions. The further instructions were provided by the commanding officer of the base. My mother was handed a piece of paper at her work and also told to go home and follow those written instructions. And what the instructions said was: ‘Get your suitcase and sit in your front yard and wait to be picked up.’ Period. So that’s what we did. We did what we were told.

We were picked up by something called a cattle-car, which was like a tractor or truck, open-ended in the back. There weren’t any seats, you had to stand up. We were taken to the docks and turned back – they said the ships were all full. So, we went to the airport and we were put in line to go on to a military transport. I walked away from that line and took a photograph of that aircraft – I probably wasn’t supposed to be doing that – and my mother and my brother waiting in line. The military personnel – my dad and the rest of the servicemen that were stationed on the base – were not evacuated. They stayed and did their duties.

My family happened to be on the very first plane that arrived in Norfolk, Virginia, the same day. All the dependents who were evacuated by ship arrived three days later. When our plane arrived – because it was the first plane from Guantanamo Bay to land on American soil – we were greeted by reporters, and flashbulbs were going off. I believe that they thought that the families of the brass, the commanding officers’ families, would be on that plane, and that is not how it worked out; we were just ordinary folks.

The most significant thing I remember about that first day being back in the United States was that evening, was John Kennedy’s speech on the radio, and it was broadcast overhead in the barracks. I remember sitting on a bed, listening to his voice for the first time. It was 1962. He’d been President for two years, and I’d never heard his voice.

John Guerrasio was a child in Brooklyn at the time and remembers the fear that ordinary people felt.

We grew up getting under our desks at school all the time for nuclear attacks. In my childhood, I think it was every Friday the air-raid siren would sound, and we would either practise getting under our desks or we’d all form orderly lines and go down to the basement.

I remember sitting down with the family and watching Kennedy’s speech and thinking the world was going to end any time now. And then there was some point in the crisis when it looked like it was very, very bad, and my mother called all of her six children into the kitchen and said, ‘We may not see each other again. The world may end this afternoon.’ And we said a prayer. And she had found some poem which described New York City in a nuclear attack with the skyscrapers forming canyons that filled with water like in one of these disaster movies. And she read us that poem and kissed us, and we all walked off to school thinking that that was the end of it. And I was pretty amazed when three o’clock came and I got to go home and watch the Three Stooges again.

The atmosphere in Russia was the same as in previous crises – we worked, we understood it was dangerous, but we believed that, we hoped that the government would resolve this crisis. If not, what can you do? So each morning, I went to my design bureau, working there as usual, then I came back to my residence where I lived with my father, and we went for a walk, and I asked him what was happening there. He told me sometimes. He answered most of my questions. I asked him, ‘What is there? What is America doing?’ Sometimes he said, ‘I am tired. Let’s walk silently.’

Then came the retreat of the Russians, who decided not to continue. We never knew if in reality the missiles were here or not, if the missiles were here and the nuclear weapons were not, that was never clear, or at least I’m not clear about it. But when the Russians accepted the inspection on the sea and when the American ships blocked them and made them go back, we didn’t expect anything else, we just trusted the revolution and its leaders and that is what is important.

I remember the day that Fidel stated the Five Points, when he did not accept the American inspection, when he did not accept that there were missiles on Cuban soil. I was studying in a night school, and I went to school and when I got there I was told that Fidel was going to speak. We started to listen to his speech at school and on our way back home we continued listening to the speech because you could hear it from every house and there Fidel took the position of total defence of Cuban sovereignty, not accepting the inspection of our national territory.

As a teenager, I believed that Castro and Khrushchev were both maniacs, crazy people. They were both dangerous, and the potential of nuclear war was real. But it wasn’t a primary concern, probably because we were so protected.

We never thought about the Cold War. We had an aggression: financial, economic, military. So, we were in a hot war, not a Cold War. We lived it.