IN THE AUTUMN of 1989 the East German authorities were facing mounting civil unrest and insistent calls for the lifting of controls on emigration to the West. Over the summer, tens of thousands of East German holiday-makers took advantage of Hungary’s decision to dismantle its border fence with Austria and poured into Western Europe. It was the largest exodus of East Germans westwards since the Berlin Wall went up in 1961, and it set in motion a dramatic chain of events that no one was expecting, not in Moscow nor East Berlin nor indeed in the Western world.

When East Germany eventually closed its border with Hungary, East Germans wanting to leave trekked across the open border into Czechoslovakia instead and either slipped into Hungary from there or sought sanctuary in the West German Embassy in Prague. Eventually, the East German government gave its consent for those holed up in the embassy to leave for West Germany in special sealed trains, stripping them of their right to East German citizenship. But then, in early October 1989, it shut off all escape routes out to the West via East European countries. East Germany was now effectively sealed off. Disaffected East Germans had no other option than to join the rallies that were spreading throughout the country, as citizens took to the streets to vent their frustration.

On successive Mondays, the numbers attending the weekly mass protest rallies in the East German city of Leipzig, which had begun in September 1989, continued to escalate. By Monday, 16 October, the crowd numbered tens of thousands of people. Two days later, Erich Honecker, the hard-line East German leader who in 1961 had supervised the building of the Berlin Wall, was forced to resign and was replaced by his deputy.

Honecker’s resignation signalled a dramatic shift. It came only ten days after celebrations in East Berlin to mark the 40th anniversary of the East German republic. In his trademark homburg hat and raincoat, Honecker stood rigidly next to his guest of honour, the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, as they reviewed a night-time military parade and declared that the socialist accomplishments of East Germany had endured for 40 years and would still be there beyond the year 2000. But Gorbachev and his aides had already made clear in private that Moscow would no longer intervene militarily in Eastern Europe. He used his trip to Berlin to warn Honecker that he must cooperate with all sections of society or ‘life punishes those who come too late.’

With Honecker gone, the protest movement continued to grow. Despite attempts by the government to clamp down, people refused to be intimidated by threats of arrest from the East German police and plainclothes agents of the Stasi state security. On 4 November hundreds of thousands of East German citizens gathered in Alexanderplatz in East Berlin to demand political change, the largest demonstration there had ever been in the country.

On 9 November the East German Communist authorities decided there was no option but to cave in and ease up on exit restrictions for those wanting to travel to, or leave for, the West. The idea was to allow a more orderly exodus into West Berlin and West Germany via existing crossing points from East Germany. The plan was for new regulations to take effect the following day. But not all the details were fully communicated either to East Germany’s border guards or to the East German Politburo spokesman, Günter Schabowski. At a chaotic press briefing that evening, he told assembled journalists that, as far as he knew, the new regulations were to come in ‘immediately without delay’, including in Berlin.

Journalists rushed to report the historic news that the border restrictions were being lifted and ‘the gates in the Wall stand wide open’, as one West German correspondent put it. The news reports were beamed straight back into East Germany. Almost immediately that night, East German citizens headed for the checkpoints between East and West Berlin and demanded to be allowed through.

The bewildered border guards had no instructions and did not know what to do. They were unable to clarify with the East German authorities whether they were supposed to block the exodus using force. Vastly outnumbered and without clear orders, they decided to give way. Soon, eager East Germans were swarming past the checkpoints into West Berlin, the border guards giving only a cursory look at their documents. Before long, young people from both sides were leaping up on top of the Berlin Wall to celebrate. Souvenir hunters attacked the Wall with hammers and chisels, demolishing parts of it and creating several unofficial openings.

It was a momentous event. The most potent symbol of a divided Europe was literally being torn down by the very citizens who had been oppressed by it. Official demolition of the Berlin Wall would not start until June 1990 and was completed only in 1992, but it was the beginning of the end of the Soviet hold on Eastern Europe.

It was also the start of frenzied, breathless negotiations over what would happen next to East and West Germany. On 28 November 1989 the West German Chancellor, Helmut Kohl, startled Western powers and the Soviet Union by presenting a ten-point plan for eventual German unity, starting with closer cooperation between the two states. By the summer of 1990, the deal for reunification was all but done.

In March 1990 the ruling East German Socialist Unity Party – which had hurriedly changed its name to the Party of Democratic Socialism, to no avail – was trounced in East Germany’s first free elections. The coalition government that replaced it called for reunification as fast as possible. The country’s economy was near collapse and in May a new treaty set the stage for legal, economic and social union between the two states. In July, the West German Deutschmark was introduced to replace the worthless East German currency, creating a monetary union, and West German laws came into force in the East.

In the international arena, the idea of German reunification initially dismayed many West European powers. Britain’s Margaret Thatcher, in particular, worried that Germany would once again become an expansionist power and a destabilising force in Europe. But European concerns were overcome by the United States, which threw its weight behind the idea, so long as the new enlarged German state stayed within NATO.

The Soviet Union at first called for a new united Germany to be made a neutral power, outside NATO and with no nuclear weapons stationed on its territory. Eventually, Gorbachev shifted his position to say that ‘the Germans must decide for themselves what path they choose’, provided that no foreign NATO troops or nuclear missiles were deployed in former East Germany.

In later decades, Gorbachev was to complain that NATO’s subsequent expansion into Eastern Europe ‘violated the spirit of assurances’ he was offered at the time, though he made it clear that no promises were given. The Russian President, Vladimir Putin, went further to claim the West had lied to Russia by failing to keep to a pledge not to expand eastwards. This complaint was to become a major source of his subsequent hostility towards NATO. In 2015 the Russian Federal Assembly even contemplated passing a motion to condemn what it called the undemocratic ‘annexation’ of East Germany by West Germany. But West German and US negotiators involved at the time have since insisted that any assurances given to Moscow in 1990 only referred to former East Germany, and the question of possible further NATO expansion eastwards was never raised.

Moscow’s acquiescence to the deal was also coloured by an agreement reached between Gorbachev and Kohl, whereby West Germany agreed to ease the Soviet Union’s spiralling economic problems by paying billions of dollars to shoulder the momentous task of withdrawing and rehousing the hundreds of thousands of Soviet troops who were stationed in East Germany.

In September 1990 the four post-war occupying powers – the United States, the United Kingdom, France and the Soviet Union – signed an agreement to confirm a settlement for Germany. The final step came on 3 October 1990, when the five states of East Germany were absorbed into the West German federal state and the black, red and gold flag of what was now a new united Germany was raised over the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin.

For all Germans, die Wende – the period of sweeping change that was triggered by the fall of the Berlin Wall – was a complex process of rehabilitation. For the government, there was the costly business of reconfiguring the two German political structures and the enormous sums to be poured by West Germany into the East to rebuild and reshape its economy. For ordinary people, the vast differences between East and West meant walls had to be broken down socially and psychologically.

For some in the East, the Wende marked a positive turning point in their life, a chance to travel, speak freely, start a business for the first time, or otherwise change their profession or place of residence. For other ‘Ossis’, as citizens from the East were called, it was a turn for the worse, their lifelong employment terminated when a workplace closed down, leaving them redundant and disorientated, with no savings or property to fall back on. Especially for older people, who found it harder to find another job, there was a sense of loss, their identity as East German citizens snatched away and replaced by a disquieting feeling that they had become second-class citizens.

For ‘Wessis’ too, as those from the West were labelled, there was a price to pay, as the country absorbed the cost of reunification and acclimatised to the huge influx of new citizens from the East, some of them with a markedly different outlook on life.

And for citizens in West Berlin there was both loss and gain. On the one hand, no longer were they hemmed in. For the first time, they could get out easily into the East German countryside. But on the other hand, West Berlin had been a unique Cold War community, cossetted and protected, overseen by the Allied occupying powers. When the Wall came down, its citizens were deprived of their special status and the reunified city, now the capital of the reunified country, had to carve out for itself a new distinctive character.

On both sides of the now demolished Cold War divide, everyone had to make an adjustment to a tumultuous, historic change which, even months before, few of them could have foreseen would turn their world upside down.

In 1989 Gisela Hoffmann was teaching English in a secondary school in Röbel, a small in town in Mecklenburg-Hither Pomerania, to the north of Berlin.

We saw that there were changes in the Soviet Union. There were changes everywhere and I thought, ‘If nothing is going to change here, I have to change myself’ – and the change for me was to stop working as a teacher and to do something else. But I didn’t stop teaching because the changes began here. The demonstrations began, in Leipzig first and then they began in our region too. We met every Monday and we had discussions, and I saw who came to these meetings and who didn’t.

We met in our marketplace. Sometimes there were 50 people, sometimes 100. We discussed, for example, with our mayor what had to change in the town; we discussed how we did not want to be observed by everybody and we did not want to send all our boys to the army or the Stasi … They asked us as teachers to send the boys to the Stasi but I said no.

Elisabeth Heller was in her early forties, a single parent with a son in East Berlin, and working as a music producer with Radio DDR 1, one of the East German state broadcaster’s stations.

We were only allowed to play 40 per cent of music from the so-called non-socialist countries and 60 per cent from our country and the socialist countries. These were the guidelines and then the singers and composers needed to adhere [to] the party line or at least appear to do so. For example, when a composer had left for the West, we were suddenly not allowed to play singers he had composed for any more. And that was the problem – since 1989, more and more artists had defected to the West. At the end, we didn’t know who to play any more because they were taken out of the card index.

Everybody had the feeling, during that time, that something had to change or was going to change. But no one had an inkling that the Wall would actually fall, and certainly not so fast.

That summer, Katharina Herrmann had just graduated with a degree in sociology, and took one last long holiday, in Bulgaria, before taking up her first job, in East Berlin. On her way home, she passed through Hungary, which had recently opened its border to the West.

I went to Budapest for a bit of sightseeing, and shopping for records which were not available in my home country. I was actually actively avoiding the groups of people who seemed to gather in these areas – I was on my way home, I had finished university, I had a job going. I absolutely didn’t want to get mixed up in that sort of thing. I did not want leave my country. I didn’t really want to associate with the people who did because I didn’t think that was the right way to go. Being young and idealistic, I always thought it would be better to work on what we had and make it work better and improve it. I always thought leaving was a bit of a cop-out. There was the question of what would happen in the long run, but we all assumed that some sort of order would be re-established, though how was not clear. This had positive outcomes for the people who stayed behind. For example, I was desperately trying to find a flat in Berlin – because so many people had left at the time, it was easier for me to find one, which was quite unusual.

I never sensed the Wall would fall soon – I was assuming that some sort of order would be re-established. I didn’t assume the Wall would fall until the day it happened.

I experienced the fall of the Wall, like thousands of people, as something really unbelievable: joy, pure happiness, euphoria all the way. We all wanted to test if it was really possible as a Berliner to go from the eastern part into the western part.

I had a visitor from Thüringen and the reaction was: ‘We have to go there immediately!’ But as dutiful as I was, because I was on leave looking after my ill son, I said, ‘That’s impossible, if someone sees me, I am on sick leave and haven’t gone to work.’ Even in that moment you were intimidated and you couldn’t believe it, but, of course, the wish was there, to test this as soon as possible.

After an exciting night, on the next day, 10 November in the morning, we went to the Wall. The first thing we saw was people, people, people, and more people who moved in clusters in the direction of potential crossing points. I only needed to have my pass stamped. We should have got a permit first, but we were allowed through anyway: a stamp and then across the bridge.

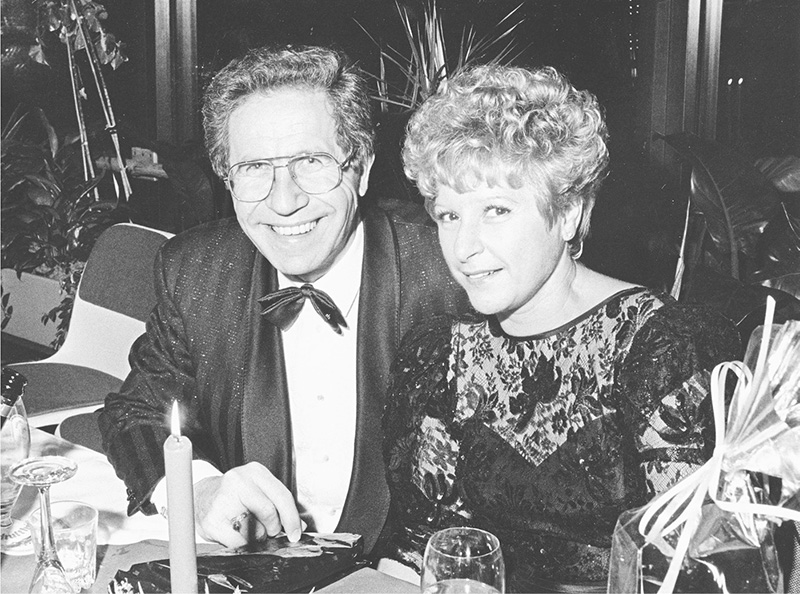

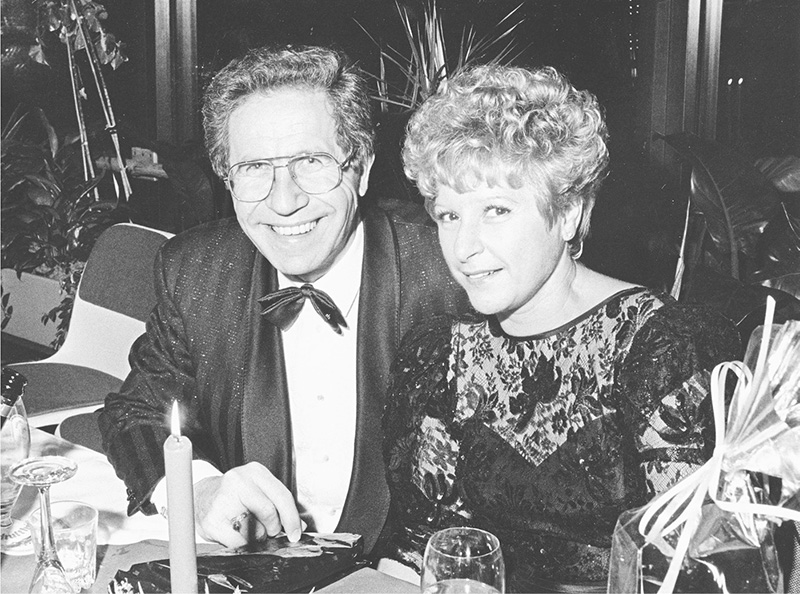

On the other side of the Berlin Wall, Otfried Laur, manager of a club for West Berlin theatregoers, was also filled with joy on the evening of 9 November.

That was one of the greatest and most beautiful days of my whole life. We were invited to a birthday party for Ulrich Schamoni, the famous theatre person. And suddenly a murmur spread through the hall, and artists from East Berlin, like Helga Hahnemann and many others I knew, came in. We were celebrating, but then we stormed out to the Wall to experience that for ourselves: how the East Berliners came to West Berlin and we could welcome them. Of course, we also had relatives in East Berlin. We telephoned them at once and arranged to meet the next day and with a big bottle of champers we then celebrated by the Wall. It was, of course, wonderful.

For me personally, work started straight away. I immediately grabbed the chance: two days later, a bicycle courier cycled over to the artistic directors of the East Berlin theatres with our brochures to introduce us as the Berlin Theatre Club. We said: ‘We would very much like to include the productions of the East Berlin theatres in our brochure for our West Berlin members.’ Crucially, we offered to pay the theatres in the East the same amount in western Deutschmarks as we paid to the theatres in the West.

We were pushing at an open door. After just two months, from January 1990 onwards, we already had all Berlin’s theatres and we could release a brochure for the whole of the city. I sat at my typewriter, with tears in my eyes when I could write for the first time ‘Staatsoper’ and ‘Friedrichstadt-Palast’ and ‘Metropol-Theater’ and ‘Deutsches Theater’. That was, for me, very emotional.

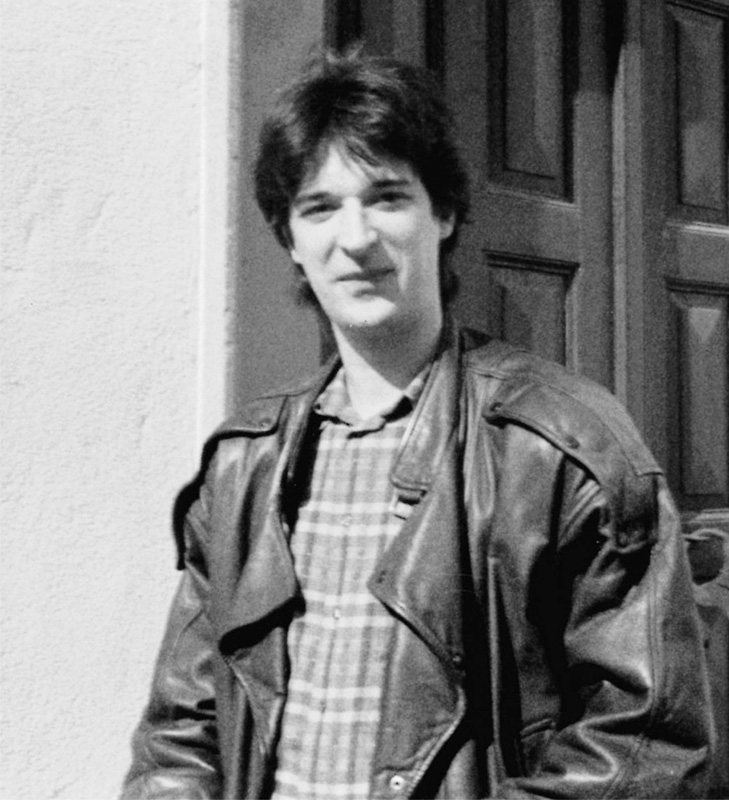

Andreas Austilat, a 32-year-old journalist in West Berlin, was otherwise engaged.

We’d packed all our things because we planned to move the next day with all our furniture to another apartment. So our TV was packed, but we had a radio, and I noticed that something was happening at the border and I told my girlfriend, ‘Well, it sounds as if they will open the border.’

The next morning, when we tried to get to our new apartment, which was in the centre of West Berlin, the streets were crowded with people from East Berlin. I think even the subway station was closed. That was the moment when we noticed, ‘Wow, the borders are really open and they are all coming to us,’ which was very strange at first.

It was a big surprise. The happiness lasted several hours because we had friends in East Berlin. They called us and came to visit us. That was so amazing because, you have to imagine, up to this point we could visit them but it wasn’t possible for them to visit us. So, it was always an artificial relationship because we couldn’t show them how we lived.

In the first few days, things weren’t really clear. Is it stable? Can we cross the border without our documents? Could they close the Wall again? Because it was so new and so surprising, we actually didn’t really know what was happening.

It was finally possible to travel in all directions without any restrictions. Without having scissors in your head [censoring yourself] and speaking freely without being afraid of things, to be able to vote freely and to enjoy tropical fruit, because that was a desire we all had.

The effect it had on my work as a music radio producer was positive in every way. We finally could make programmes with the music we always wanted. It was also significant for producers in the other departments. And we did everything to make a fresh start in the [East German] media.

I felt wonderful and free as never before. I had enjoyed doing the work before, but this was a feeling that I experienced only at this time. Not before and not after. You finally had the feeling you were recognised, you were taken seriously. You did not have the feeling any more of being a second-class person, and constantly being pushed around or having to adhere to regulations. It was like a dream.

Once we realised it was probably a permanent feature, there obviously was a sense of adventure. But also the question – what now? Is everyone going to go? Are lots of my friends going to leave? And if so, where to? It was incredibly exciting to think about travels that might be possible in future. But it was also very worrying to think about my professional future because I was quite aware of unemployment rates for people of my professional background – I was a trained sociologist. In Germany, you are quite linked to your professional qualifications, so it’s quite difficult to switch from your chosen subject to another without retraining.

I was quite taken aback when very soon there was talk about unification. I was born a very long time after the war and the building of the Wall. I didn’t really consider myself as part of a larger Germany; I didn’t have much in common with a lot of the West Germans I met because of the different ideology. I had a lot more in common with a lot of Czech and Polish people I knew at the time in my way of thinking and how I saw my future. Being reunited was an alien idea to me. I would have thought and hoped that there would be a getting-closer process as part of being in the European Community – that was the process I would have liked much better.

I wanted to be part of this new time. They asked me to become headmistress of the school. I helped to change my school into a grammar school. Before that, there was no grammar school in my town. All the students who wanted to take the Abitur [advanced level school exam, taken at 18] had to go to the neighbouring town, which meant travelling 20 kilometres every day by bus. We wanted to have that in our town, too, and we wanted to give more students the opportunity to take the Abitur. Before, only pupils who were chosen could take it, and the parents had to be in the party. The really good students were not chosen to take the Abitur, but rather students who had the ‘right’ family.

For Andreas Austilat, the fall of the Berlin Wall meant he could now visit the countryside outside Berlin.

We went to the south-west of West Berlin, the former border. The border was still there, of course, but it had holes in it. We noticed two young soldiers with their car, a military vehicle. My girlfriend told me that she would like to have a souvenir. So, I came to the former Wall, with its holes, and asked a soldier. First I called: ‘Would you please come over here?’ And he said, ‘Yes, what’s happening?’ Which was a strange situation because several weeks before he would have shot me. I asked him, ‘We would like to have a buckle from the belt from the National People Army, the East German Army.’

And he wasn’t as astonished as I thought he would be. He said to me, ‘Okay, no problem,’ turned back to his vehicle, and took out a couple of belts. And he asked me: ‘What do you want? Fabric or leather?’ And I was so surprised that meanwhile he changed from soldier to a kind of merchant.

Well, I bought the belt, the buckle, a medal and his cap. It was a funny situation. It showed how much had changed. Because these soldiers – before, they were very strict, and kept their distance and were very cold – and now you could talk to them easily and buy their belt buckles. That was new.

From the perspective of some East Germans, reunification with the West was a mixed blessing.

I was not entirely happy or excited. I really resented the idea of success being measured in money – which would become part of our future lifestyle. I very much resented the West German body of law being implemented as part of a reunification process – that was about things that affected me as a woman. For instance, the law on abortion would change, and as far as I was concerned, it would go backwards 30 years. Generally, the perception of women working in the West of Germany was very different than the East, where over 90 per cent worked, and that was what they expected to do once they left education regardless of whether they had a family or not. Also the whole image of women in the media was very different from what I was used to and what I liked.

I had to totally re-evaluate what I wanted to do with my professional life. It totally changed the range of options available to me. I had grown up being quite concerned about potential unemployment, and I did become unemployed soon after the Wall [came] down – but I had underestimated my own ability to deal with that. I was able to go much further, not just in terms of moving country but also professionally, than I had ever expected myself to be able to before I found myself in that situation. A lot of the things I worried about at the time didn’t come to pass, but other things I hadn’t prepared for did. I have made the most of it.

The unification of Germany involved bringing together many institutions from West and East – or, in some cases, the closure of the East German version, such as the state radio broadcaster to which Elisabeth Heller had dedicated her career. So, just under a year after the fall of the Berlin Wall, things began to change.

For the first station, Radio Berlin International, the fun was already over. For me, working for Radio DDR 1, which was renamed Radio Aktuell, the end came a year later. I personally had the feeling of someone cutting my throat. Consternation, bewilderment, deep sadness, lack of understanding, because no one could understand that. You did your best, you’d invested everything, you were happy – and suddenly it was over.

There were measures by which they thought they could redeploy people but, as it turned out, that was an illusion. I had to go to the job centre, where I was told: ‘At the age of 42 and with a child, you will never get a job again – you better marry a rich man.’ I was left to my fate – no one helped me because everybody was busy with him or herself. We were almost like a family, and suddenly everything was gone. Nothing was like yesterday.

People probably expect big sweeping statements about feeling free, about the wonders of democracy. I didn’t really feel as unfree as I probably should have felt in the eyes of a Westerner in East Germany. The main thing I was unhappy with was not being able to travel. I didn’t rail against the system. I liked this type of egalitarian society. I actually quite liked the idea that there were no extremely rich people. At the same time, there was free healthcare for everyone. I could see the good sides there.

Sometime after the fall of the Wall and the whole unification process, I started to develop a feeling as if I was a second-class citizen. I didn’t really think of myself as a German at the time – I thought of myself as an East German, but that wasn’t really the accepted opinion any more. I was very unhappy and upset about the way the whole unification process went because I think the word ‘unification’ is a bit of a misnomer – it was a takeover. There was actually very little that was positive about Eastern laws, regulations, life circumstances that was adopted into the unified Germany, so it felt a bit like being colonised. There was the assumption that if you were in or from the East and you weren’t an active dissident, you were automatically a Stasi member, or somebody who had totally wrong and undemocratic ideas. There was the assumption that you would immediately accept West was good, East was bad. There was a lot of deliberate misinterpretation about what had been going on in East Germany. There was a lot of very negative propaganda about people like my parents, for instance, who had spent their lives trying to build on something very worthwhile and positive – an egalitarian social experiment, no matter how flawed. That did not make them bad people who had supported the wrong thing. But the assumption was that if you were not against the system you were automatically a Stalinist, and that was really wrong and very upsetting.

There was also the assumption that if you’d trained or gone to university in the former East, it automatically would be worse. The education process was quite comprehensive – you had to learn several languages even to be admitted to university.

I found there was a lot more emphasis on appearance than there had been among my friends, at least in the East. Clothes were hugely important to a lot of people I met from West Germany. I was far more interested in substance over style, I was never particularly interested in fashion. I had some very strange experiences trying to go shopping in big department stores and asking for something like plain black trousers. I was told by the shop assistant this wasn’t fashionable at the moment so this would not be available. I remember finding that quite weird. This was partly to do with being brought up on the propaganda that everything was there for sale in the West, if only you had the money to pay for it. There were quite big differences in the shopping culture, but a lot of it was really quite disappointing. You were told by advertising that the customer is king; I found a lot of people, when I went shopping, quite dismissive of me.

I suddenly found myself in a strange country, although I hadn’t changed location, and in that strange country, whose laws weren’t clear to me, I became unemployed – a situation I hadn’t known in the country I had grown up in, where everything, from the cradle to the grave, was taken care of. You had the feeling of being a nothing. You always had the feeling of having to justify yourself to other people who didn’t understand why you were unemployed and had no job. It was an exasperating state, which lasted until I reached pensionable age.

During that time I did all sorts of things, always in the area of media and education, but it was always short-term, such as three weeks covering someone’s leave at a broadcasting station here, or a several-week or month-long retraining course there. Or a so-called job-creation measure, where people came together who had no clue what to do with one another, because they came from all walks of life. As far as I can remember, the people were just frustrated – in despair and frustrated. In the end, it was just a fight for survival, in which one didn’t know what best to do and one practically did not have any support. Nobody supported me except for one so-called case manager, who recognised what a desperate state I was in. He enabled me to do a distance-learning course and to get a digital recording machine. Apart from that, I was always treated like a second-class person. Humiliations without end – and that has consequences. Your self-esteem disappears.

It was so difficult to get a foothold because I was not the only one. There were many others who were looking for work. I was always told: ‘You are overqualified and too old.’ It was difficult to convey to your own child that education would be of use, because I did several further training courses in the area of media education and multimedia. I did a long-distance course in the care of the elderly, in the hope that I could teach students of that subject. They were all delighted with my work, but said: ‘No, but we are not able to pay you.’

I became more open to the world. I found out that it is normal to go to other places because you find normal people there. They are not so different from us. When you are friendly to them, they are also friendly to you. And when you show interest in them, they also show interest in you. And for me it was also very interesting when we went to London for the first time, to see all the people coming from all over the world. We hadn’t seen any people from India or from Jamaica, or from anywhere else. It was very, very strange for us, but they behaved so normally and they were normal people of England. And that was also a very interesting idea for us.

Before, I could never speak more than three or four sentences in [English]. I never taught an English lesson entirely in English. We spoke a lot of German in our English lessons because we only had the vocabulary and the grammar, and we explained everything in German. Later, with a colleague, also an English teacher, I organised a 14-day trip to England every summer holiday. The students who came with us wanted to learn English. They were very interested. They took all the opportunities to speak English and we asked them to do everything that was necessary. We let them do the check-in in the hotels, we sent them to buy things we needed for our meals or we sent them to get tickets at a theatre or for a musical and so on. We let them organise a meal at a restaurant for a whole group. And they did it, and they did it very well.

Katharina Herrmann, fed up with feeling like a second-class citizen in the new, unified Germany, moved to London.

Moving from East Berlin to London has made me a lot more confident than I ever thought I would be, a lot more outgoing. When I was young I was the kind of person who sits in a corner and reads a book, who doesn’t particularly talk to other people unless they are spoken to, quite cerebral, quite shy. Because of the way my life has developed, I absolutely had to come out of that shell to a much, much larger extent than I ever thought I could or would. There have been moments when I missed my quiet life and when I found it very onerous to do this, but in the long run I have lived far more up to my potential than I would have otherwise.

For me, [the big thing that was not possible before] was the ability to go and see places I had never imagined I would see – and that was something I was systemically working on to make that possible. After I had moved to London, got a job here, I spent a lot of effort trying to save my money and use my annual leave to go to places like China, India, Japan – places I’d always looked at with some sort of mystical aura – ‘I’d love to see that, it’s so different, but it’s not likely to happen.’ I had a huge collection of books on India and China, for instance, while I was still a student in East Germany, but I never at the time imagined, reading all that stuff, that I would be able to go and see that. That really is one of the great outcomes.