1

A MATTER OF TRUST—MAKING MEDICINE OR MAKING MONEY?

“Where large sums of money are concerned,

it is advisable to trust nobody.”

—Agatha Christie

IS IT REALLY POSSIBLE that American baby boomers and younger generations have been led down a road to poor health by the pharmaceutical industry and conventional medical practice? Have the very industries, organizations, and medical doctors responsible for designing our health care system created the catastrophe of skyrocketing medical costs? Are the drug companies so powerful that they exert virtually complete control over the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), medical schools, prestigious medical journals, and continuing medical education for physicians? Is it true that adverse reactions to over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription drugs are estimated to kill over 100,000 Americans a year, making these reactions the fourth-largest cause of death in the United States, behind cancer, heart disease, and strokes?

The answer to all these questions is yes. The pharmaceutical industry and the medical monopoly have created a health care crisis in America. In this book, we will, together, take a peek behind the curtain to expose some of the fallacies and shortcomings of many popular medications. It is absolutely true that most of us have been helped in almost magical ways by the wonders of modern medicine, but the reality is that conventional medicine has also created a lack of personal accountability and a complete reliance on little pills to cure what ails us. We now have on our hands a modern epidemic, consisting not only of diseases that are clearly a result of diet and lifestyle, but also of diseases due to the side effects of drugs used in their treatment.

The United States has by far the highest per capita use of conventional medicines and uses over more than 40 percent of all of the drugs produced in the world each year, according to the World Health Organization (WHO); but we are only forty-second in terms of life expectancy. We are definitely not getting our money’s worth from our medicine. It is easy to demonize the greedy pharmaceutical industry, but the problem is much deeper than that. It is also easy to say that most medical doctors have simply been unknowing pawns in the drug companies’ game of profits, never realizing that they have been led to perpetuate lies, half-truths, and incomplete science; but the reality is that the medical profession has done a questionable job in protecting the health of the patient. In fact, many doctors are willing players in the game. They do not mind. It represents easy money. The average income for a medical doctor is more than $200,000 per year, and many specialists, such as radiologists and heart surgeons, have an average income of more than $300,000 per year. It could be that there is one very big reason why many medical doctors do not practice preventive medicine—money. The average yearly income for a member of the American College of Preventive Medicine, a group of preventive medical doctors, is $100,000—a good income, but considerably less than half the average income for other medical specialties.

Also, it is estimated that drug companies spend more than $57.5 billion a year marketing to physicians. This figure includes about $14 billion for what is referred to in the industry as “unmonitored promotion” it can include lavish vacations and getaways, ostensibly continuing medical education. With about 700,000 practicing physicians in the United States, it is estimated that the drug industry spends about $60,000 in marketing per physician.1

Do the Drug Companies Spend More on Marketing or Research?

According to a very detailed analysis by two Canadian researchers, Marc-André Gagnon and Joel Lexchin, “The Cost of Pushing Pills: A New Estimate of Pharmaceutical Promotion Expenditures in the United States,”1 drug companies spend twice as much money on marketing as on research and development. Now, the U.S. General Accountability Office (GAO) says otherwise. Why the discrepancy? Well, it turns out that the data supplied to the GAO are from IMS, a firm specializing in pharmaceutical market intelligence. There are many concerns about the accuracy of the IMS data, chief among them being that the data are derived by asking the drug companies to supply them. The bottom line is that the IMS data are simply not consistent with other published sources, including data provided by the U.S. Office of Technology Assessment as well as information gathered from year-end financial reports from the drug companies themselves.2

DRUG COMPANIES, PROFITS, AND THE FDA

If anyone knows the depth of the deceit and false promises heaped on Americans by drug companies, it is Marcia Angell, M.D., former editor in chief of the New England Journal of Medicine, one of the most respected medical journals in the world. According to Dr. Angell, the pharmaceutical industry “has moved very far from its original high purpose of discovering and producing useful new drugs. Now primarily a marketing machine to sell drugs of dubious benefit, this industry uses its wealth and power to coopt every institution that might stand in its way, including the U.S. Congress, the Food and Drug Administration, academic medical centers, and the medical profession itself.”3

There is now considerable evidence that the drug companies exert significant control over the FDA and the drug approval process. More than half of the experts hired to advise the FDA on the safety and effectiveness of drugs have financial relationships with drug companies that will be helped or hurt by their decisions. Federal law generally prohibits the FDA from using experts with financial conflicts of interest, but the FDA waived this rule 800 times in a 15-month period from January 1998 to June 2000. In an analysis of all advisory panel meetings from 2001 to 2004, at least one member had a financial link to the drug’s maker or a competitor in 73 percent of the meetings.1, 2 The potential damage from such ties was exemplified in 2005, when the FDA convened a meeting to discuss the toxicity of the COX-2 inhibitors Vioxx, Celebrex, and Bextra. Had the ten committee members with ties to industry been precluded from voting, the committee would have voted against continued marketing for Vioxx and Bextra; instead, all three drugs received favorable votes.3, 4 As a result these potentially dangerous drugs were allowed to stay on the market. That trend has created a huge problem, because 20 percent of all approved drugs over the last 25 years were later found to have serious side effects leading either to the withdrawal of the drug from market or to warning labels noting these serious side effects. The drug companies could afford to take a gamble on drugs like Vioxx, Celebrex, Avandia, OxyContin, and others because of the huge profits they could generate.

Since the 1950s, drugs have been the most profitable industry in America. In December 1959, the last year of the Eisenhower administration, the Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly reported on a yearlong investigation of the drug industry with the declaration that the public was not only being overcharged for drugs but was being ripped off for useless and sometimes harmful medicines. Three charges were leveled at the drug industry by the subcommittee: (1) Patents sustained predatory prices and excessive margins. (2) Costs and prices were extravagantly increased in order to fund marketing expenditures. (3) Most of the industry’s new products were no more effective than lower-priced, established drugs on the market. Back in the 1950s, this report changed the image of drug companies: the companies had been seen as employing lifesaving “researchers in white coats” but were now seen as employing primarily zealous “sales reps in cars.”

Has the situation changed in the last 50 years? Yes: it has gotten much better for the drug companies, at the public’s expense. During the past 50 years drug costs have skyrocketed at a rate five times inflation. In 1960, the drug industry had a profit margin of 10.6 percent of sales. By 1992, this had increased to 13 percent. In 2005, it was 18 percent. Pfizer, the world’s number one drug company, had a profit margin of 26 percent of sales.

In 1980, the average prescription cost $6.52; in 1992 the cost was $22.50; in 2006 it was $50.17. Drug costs are higher in the United States than anywhere else in the world. Most major industrial nations apply profit control to limit how much a drug company can charge for a drug. Because most drug companies market the same drug throughout the world, they rely on the United States for the bulk of their profits. In the United States, drug companies can increase the price of drugs without fear, because there is very little competition. In fact, there is more cooperation between drug companies to keep prices high than there is price competitiveness.3, 4

HIGHER-PRICED DRUGS + MORE PRESCRIPTIONS WRITTEN = HUGE PROFITS FOR DRUG COMPANIES

The simple sum expressed above is astronomical in real life because more people than ever before are being placed on high-priced drugs. For example, roughly 4 billion prescriptions were filled last year, about 12 prescriptions for every person in the United States. Are all these prescriptions necessary? Remember that the United States uses more than 40 percent of all the drugs in the world but ranks only forty-second in life expectancy; also, it ranks only thirty-seventh in the quality of its health system, according to WHO. The high cost of drugs is bankrupting our elderly population, and our society. The number of seniors who depend on prescription drugs is unbearable. In 1992, the average senior received 19.6 prescriptions per year; in 2005, that number had nearly doubled, to 34.4. The average person over the age of 55 is on eight or more prescription drugs at any one time.

According to a study by Fidelity Investment released in March 2006, a 65-year-old couple retiring today will need, on average, $200,000 set aside to pay for medical costs during retirement. A big chunk of that $200,000 will go to pay for expensive drugs that produce questionable results and raise considerable safety issues. For example, the current treatment of type 2 diabetes is very absurd. Now an American epidemic, diabetes is also a source of huge profits for drug companies, yet the research findings are quite clear—oral medications to treat type 2 diabetes do not alter the long-term development of the disease. Although the drugs are quite effective in the short term, they create a false sense of security: they ultimately fail and are then prescribed at higher dosages or in combination with other drugs, leading to increased mortality. That is right; the long-term use of these drugs is actually associated with an earlier death, compared with mortality in control groups of diabetics who are not given the drugs. Here are some additional facts:

It is estimated that 70 percent of patients with chronic daily headaches suffer from drug-induced headaches.

It is estimated that 70 percent of patients with chronic daily headaches suffer from drug-induced headaches. Sleeping pills interfere with normal sleep cycles, produce numerous side effects, and are addictive.

Sleeping pills interfere with normal sleep cycles, produce numerous side effects, and are addictive. Aspirin, ibuprofen, and other nonsteroidal drugs (NSAIDs) used for arthritis lead to joint destruction by inhibiting the formation of cartilage.

Aspirin, ibuprofen, and other nonsteroidal drugs (NSAIDs) used for arthritis lead to joint destruction by inhibiting the formation of cartilage. NSAIDs cause 16,500 deaths in the United States annually, and more than 100,000 Americans are hospitalized because of side effects.

NSAIDs cause 16,500 deaths in the United States annually, and more than 100,000 Americans are hospitalized because of side effects. Acetaminophen overdose is the leading cause of acute liver failure and causes 10 percent of all cases of kidney failure.

Acetaminophen overdose is the leading cause of acute liver failure and causes 10 percent of all cases of kidney failure. Drugs like Paxil, Zoloft, and Prozac contribute to obesity, but weight gain is not listed as a common side effect of these drugs.

Drugs like Paxil, Zoloft, and Prozac contribute to obesity, but weight gain is not listed as a common side effect of these drugs.

WHY HAVE HEALTH CARE COSTS SKYROCKETED?

In addition to higher-priced drugs, the reasons often cited to explain the tremendous rise in health care costs include these:

Why Was the FDA Slow to Warn Patients about the Popular Diabetes Medication Avandia?

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), the makers of the popular diabetes drug Avandia (rosiglitazone maleate) informed the FDA as early as 2005 that this drug was associated with a 30 percent increase in the risk of heart disease. Instead of acting immediately on this important information and warning patients of the potential risk, GSK took until June 2007, when a study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine, to bring this risk to light.5 The lead researcher Steven Nissen, M.D., from the Cleveland Clinic, wrote in his report that both GlaxoSmithKline and the FDA should have taken (but didn’t take) the necessary steps to adequately warn people using Avandia of the risks to their health. An examination of data from a pool of 42 studies provided by GSK showed that there was a 43 percent increase in the number of heart attacks and a 64 percent increase in the risk of dying from heart disease among people with type 2 diabetes taking Avandia, compared with people given a placebo. Keep in mind that the reason drugs are prescribed to lower blood sugar is to prevent the complications of diabetes, the most important of which is heart disease.

Given the facts that in 2006 alone, doctors in the United States wrote 13 million prescriptions for Avandia and that the results of this study were so damning, it is estimated that as many as 16,000 legal claims could be made against GSK in response to the study. But even though the FDA shares equal blame for allowing these deaths to happen, no legal action will be made against it.

We have too many doctors. The ratio of practicing medical doctors to the population went from 151 doctors per 100,000 people in 1970 to 245 per 100,000 in 1992, an increase in ratio of 62 percent.

We have too many doctors. The ratio of practicing medical doctors to the population went from 151 doctors per 100,000 people in 1970 to 245 per 100,000 in 1992, an increase in ratio of 62 percent. We have too many medical specialists. Fifty years ago, specialists were 30 percent of the physician workforce; today, specialists account for 70 to 80 percent.

We have too many medical specialists. Fifty years ago, specialists were 30 percent of the physician workforce; today, specialists account for 70 to 80 percent. There are too many unnecessary visits to doctors, medical procedures, surgeries, and drugs being administered by doctors. Currently, medical analysts estimate that 36 percent of physician visits are unnecessary, 56 percent of surgeries are unnecessary, 15 percent of hospital outpatient visits are unnecessary, and half of all time spent in hospitals is not medically indicated.

There are too many unnecessary visits to doctors, medical procedures, surgeries, and drugs being administered by doctors. Currently, medical analysts estimate that 36 percent of physician visits are unnecessary, 56 percent of surgeries are unnecessary, 15 percent of hospital outpatient visits are unnecessary, and half of all time spent in hospitals is not medically indicated.

One of the most disturbing statistics is that there is a direct correlation between the ratio of surgeons in an area and the percentage of the local population receiving surgeries. One research study found that an area with 4.5 surgeons per 10,000 population experienced 940 operations per 10,000 whereas an area with 2.5 surgeons per 10,000 experienced 590 operations per 10,000.6 In other words, when the concentration of surgeons doubles, so does the rate of surgeries. It makes sense, doesn’t it? After all, these surgeons need to perform surgeries to cover overhead and maintain their desired income. The problem is apparently worse for especially expensive surgeries. For example, according to a noted Harvard cardiologist and published studies in the Journal of the American Medical Association, more than 80 percent of coronary angioplasty and bypass operations are not necessary.7 These surgical procedures cost, on average, $40,000. The rise in expensive hospital-based procedures such as coronary artery bypass operations prescribed by highly specialized physicians is considered by health economists to be the primary cause of our escalating health care costs.

SELLING SICKNESS

As if it were not enough to gouge the pocketbooks of Americans for drugs to treat sickness, the drug companies have used their influence to narrow the boundaries of what is normal for conditions such as cholesterol and blood pressure, so that they can cast a bigger net and get doctors to prescribe their drugs to more patients. The goal of the drug companies is transparent and has been expertly revealed in Selling Sickness: How the World’s Biggest Pharmaceutical Companies Are Turning Us All into Patients, by Ray Moynihan and Alan Cassells.

The ultimate strategy of Merck, one of the largest drug companies in the world, was outlined more than 30 years ago when Henry Gadsden, the head of Merck at the time, was interviewed by Fortune magazine. Gasden said he wanted Merck to be more like Wrigley gum, that it was his dream to make drugs for healthy people so that Merck could sell to everyone.8 This dream is now nearly reality, if you take a look at the number of people currently taking statin medications to lower cholesterol. By the way, the first statin drug to be marketed was Merck’s Mevocor (lovastatin).

Selling Addiction

Oxycodone is a potent and highly addictive synthetic opiate-like pain medication marketed under the proprietary names Percocet, Combunox, Roxicodone, OxyContin, and as generic alternatives. Of these, the most notorious is OxyContin (the name is actually short for Oxycodone Continuous release) popularly referred to as “pharmaceutical heroin” and marketed as a miracle drug for people with chronic pain. On May 10, 2007, Purdue Pharma—the company that makes OxyContin—and three current and former executives pleaded guilty in a U.S. court to criminal charges that they misled regulators, doctors, and patients by falsely claiming that OxyContin was less addictive, less subject to abuse, and less likely to cause withdrawal symptoms than other pain medications. To resolve criminal and civil charges related to the drug’s “misbranding,” Purdue Frederick—the parent company of Purdue Pharma—and its top three executives agreed to pay about $634 million in fines and other charges, one of the largest amounts ever paid by a drug company in such a case. OxyContin was launched in 1995, and its annual sales reached approximately $2 billion prior to the arrival of generic products in 2004 and are still over $1 billion annually. So, although $634 million seems like a huge fine, it was still not as high as the drug company’s profits.

Sales of statin drugs such as Lipitor, Crestor, and Pravachol have reached unbelievable heights; these are by far the best-selling category of drugs. How these drugs rose in popularity serves as a model for the entire drug industry and is explained in Chapter 7. One strategy of the drug companies selling statins was to expand the number of people who met the criterion of “high cholesterol.” Every time the level of cholesterol considered “high” is lowered, millions of new customers are created overnight. Since the statins were introduced in 1987, the number of people in the United States with high cholesterol has increased from 13 million to nearly 100 million.

Who are these experts defining “high” cholesterol? Are they paid representatives of drug companies? It would seem so. Eight of the nine experts who wrote the latest cholesterol guidelines for the U.S. National Institutes of Health also serve as speakers, consultants, or researchers to the world’s largest drug companies.9 Most of the individual authors were receiving money from at least four companies, and one “expert” had taken money from ten.

DRUG COMPANIES CONTROL MEDICAL EDUCATION

Believe it or not, most physicians receive very little formal education in nutrition, and also very little in pharmacology, the study of drug actions and effects. Doctors are taught general principles of pharmacology in medical school, but most of their understanding is derived from their hospital training with practicing physicians. How do those practicing physicians learn about pharmacology? From the drug companies, of course. The drug companies sponsor medical journals and educational programs, and there is roughly one drug company sales representative for every 10 doctors in America. Doctors rely on these sales reps for information about drugs, yet less than 5 percent of these sales reps have had formal training in pharmacology.

Detailed analysis has also shown that most physicians do not decide what drug to use on the basis of scientific research or cost; they base their decision almost entirely on the effectiveness of the drug company’s marketing and advertising. In essence, doctors are often bribed or lied to so that they will prescribe certain medications. The bribing is well-known; the lying becomes apparent when we examine pharmaceutical advertisements and the manipulation of data in published studies. Here are some sobering facts:

According to former editors of three major medical journals—the Lancet, the New England Journal of Medicine, and the British Medical Journal—some journals are just an extension of the marketing departments of major drug companies.3, 10, 11

According to former editors of three major medical journals—the Lancet, the New England Journal of Medicine, and the British Medical Journal—some journals are just an extension of the marketing departments of major drug companies.3, 10, 11 An entire issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) was dedicated to evaluating the quality of research. One telling statistic: it is estimated that 95 percent of medical studies in the most prestigious journals contain false or misleading statistics.12

An entire issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) was dedicated to evaluating the quality of research. One telling statistic: it is estimated that 95 percent of medical studies in the most prestigious journals contain false or misleading statistics.12 Many research studies in medical journals are sponsored by drug companies and ghostwritten. In one analysis, 40 of 44 articles (91 percent) were ghostwritten, and in 31 articles the ghostwriter, as identified, was a statistician (and you know what they say about statistics).13

Many research studies in medical journals are sponsored by drug companies and ghostwritten. In one analysis, 40 of 44 articles (91 percent) were ghostwritten, and in 31 articles the ghostwriter, as identified, was a statistician (and you know what they say about statistics).13

DRUG COMPANIES FUND RESEARCH AS A MARKETING TOOL

The gold standard that physicians are taught to use in evaluating a drug’s efficacy and safety is the randomized, controlled clinical trial designed to eliminate all aspects of chance to provide a statistical outcome. However, this gold standard has become fool’s gold for several reasons. What the doctors usually don’t know is that they are placing their faith in research whose outcomes are largely predetermined by the drug companies’ careful stacking of the deck before the trial ever begins. The doctors do not realize that instead of using impartial, neutral research organizations, the drug companies hire for-profit contract research organizations to conduct their clinical trials.14 And virtually all the clinical research done in the United States is designed to benefit the drug manufacturers, because they are paying for it. In 1980, research sponsored by drug companies accounted for about one-third of all clinical research done in the United States. By 2007 that proportion had grown to an estimated 90 percent.15

Drug companies are very smart—remember that they are the most profitable industry in the world—but the research organizations may even be smarter! They know that in order to be successful, they must be able to produce results that will make their customers very happy. So they must assure the clients that they will produce the best possible results; and if by chance a study does not produce the desired outcome, then that study will never be published. Even if a study is published, the research organizations often withhold important data. Perhaps one of the most celebrated examples of convenient omission is the case of Celebrex. The reason why Celebrex and Vioxx came into prominence was to avoid the ulcers caused by anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin and ibuprofen. The makers of Celebrex achieved this goal when the results of two six-month studies indicated that Celebrex caused fewer stomach problems than the older drugs. But what the drug company failed to disclose was that the two studies were actually for 12 and 15 months, respectively. The reason the results were published after only six months was that with longer use—12 months—there was actually no difference, with regard to ulcers, between Celebrex and the older drugs ibuprofen and Voltaren.16, 17 In light of the subsequent disclosures about Celebrex and Vioxx, it would seem that should never have been approved for use (these drugs and their natural alternatives are discussed further in Chapter 5).

THE “OFF-LABEL” MARKET AND DRUG PROFITS

“Off-label use” of a drug refers to prescribing it for a purpose other than its FDA-approved use. In most cases, once the FDA allows a drug to be prescribed, doctors have the right to prescribe it as they deem fit. But although it is entirely legal in the United States for doctors to do this, it is illegal for drug companies to market off-label uses. Still, there are ways around this restriction. In fact, drug companies spend considerable resources to promote off-label uses.

The most notorious example of an off-label strategy involved the Parke-Davis division of Warner-Lambert (which was swallowed up by the drug giant Pfizer in 2000) and its drug Neurontin,18 which had been approved for use in epilepsy that was unresponsive to other drugs alone. Parke-Davis constructed an elaborate illegal scheme to increase the profitability of Neurontin by promoting it for other uses. Publicly, Parke-Davis/Pfizer called the plan a “public relations strategy.” Internal documents, however, detailed a well-orchestrated strategy to fund poorly designed studies for other uses such as anxiety, headaches, bipolar depression, and pain—conditions that affect much larger numbers of people than epilepsy does. Parke-Davis/Pfizer arranged for contract clinical research organizations to conduct the studies and then paid academic authors and experts to sign their names to the studies. Once published, these research articles were aggressively disseminated to physicians. Parke-Davis also sponsored educational meetings and conferences at which not only the presenters were paid: physicians in the audience were also paid to attend, or in some cases the meetings were, essentially, paid vacations for the doctors.

The strategy worked brilliantly, at least until 1996, when David Franklin, a Parke-Davis sales representative, blew the whistle on the operation. Even then, Neurontin’s sales soared from $97.5 million in 1995 to nearly $2.7 billion in 2003. In 2004, Pfizer paid $430 million to the federal government to settle the case. This fine was hardly a deterrent; more than likely, it was built into the price of the drug.

WHY IS THERE A BIAS AMONG MEDICAL DOCTORS AGAINST ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE?

The simple answer to this important question is that many doctors are simply not educated in the value of nutrition and other natural therapies; in fact, most were told during their education to tell their patients that alternative medicines are worthless. Many doctors are not aware of, or choose to ignore the data on, beneficial natural therapies such as diet, exercise, and dietary supplements, even if the data are overwhelmingly positive. Rather than admit that they don’t know, most doctors have a knee-jerk reaction: it can’t be true. If they are not up on something, they will be down on it, to protect their own ego. They often suffer from what I call the “tomato effect.” This is a reference to the belief, widely held in eighteenth-century North America, that tomatoes were poisonous, even though they were a dietary staple in Europe. It wasn’t until 1820, when Robert Gibbon Johnson ate a tomato on the courthouse steps in Salem, Indiana, that the barrier against the “poisonous” tomato was broken in the minds of many Americans.

The attitude of many physicians toward alternative therapies is quite similar to the tomato effect. For example, diet is a fundamental aspect of health. But when patients ask about diet therapy or a nutritional supplement for a particular condition, even if the nutritional approach has considerable support in the scientific literature and this literature proves its safety and effectiveness, most doctors will caution their patients against taking the natural route or will tell them that it will not help, though it won’t hurt either. The truth is that in many cases, the doctor just doesn’t know anything about it. There is more to this story; I will discuss it in Chapter 10 and will also point out that:

It took the medical community more than 40 years to accept the link between low levels of folic acid in pregnant women and neural-tube defects in newborns. It is estimated that 70 to 85 percent of more than 100,000 cases of spina bifida in children born during that time could have been prevented if doctors had not been so biased against scientific data on nutritional supplements.19

It took the medical community more than 40 years to accept the link between low levels of folic acid in pregnant women and neural-tube defects in newborns. It is estimated that 70 to 85 percent of more than 100,000 cases of spina bifida in children born during that time could have been prevented if doctors had not been so biased against scientific data on nutritional supplements.19 The true number of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) may be even more than 2 million per year, because ADRs are underreported to the FDA (reporting is a voluntary program). For example, the FDA receives an average of 80 reports each year about adverse reactions caused by the drug digoxin; however, a systematic survey of Medicare records indicates that approximately 30,000 hospital admissions each year are for digoxin toxicity.20

The true number of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) may be even more than 2 million per year, because ADRs are underreported to the FDA (reporting is a voluntary program). For example, the FDA receives an average of 80 reports each year about adverse reactions caused by the drug digoxin; however, a systematic survey of Medicare records indicates that approximately 30,000 hospital admissions each year are for digoxin toxicity.20 In the worst-case scenario, over the last 20 years ephedra and other natural products were linked to approximately 150 deaths (virtually all of which were related to excessive dosage or abuse). In contrast, over the last 20 years approximately 2 million people in the United States died from adverse drug reactions; these deaths included more than 300,000 caused by aspirin and other NSAIDs.21

In the worst-case scenario, over the last 20 years ephedra and other natural products were linked to approximately 150 deaths (virtually all of which were related to excessive dosage or abuse). In contrast, over the last 20 years approximately 2 million people in the United States died from adverse drug reactions; these deaths included more than 300,000 caused by aspirin and other NSAIDs.21

HEALTH CARE VERSUS DISEASE MANAGEMENT

Talk of health care reform is everywhere. It’s was the hot political topic of the 1990s. For good reason, the cost of health care in America is wildly out of control. However, fundamentally, what is being debated is not “health care” reform but the reform of “disease management.” The U.S. system is not devoted to promoting health. It is obsessed with managing disease. In fact, the combined influence of the pharmaceutical industry, the FDA, and public policy has taken “health care” virtually out of our system.

Everything in our system depends on people’s getting sick. The basic treatments covered by medical insurance revolve around patented pharmaceutical drugs, designed to suppress the symptoms of disease, and expensive surgeries. No one involved in the medical industry really wants to see true health care reform. Managing disease is simply too big and too lucrative a business. This might make sense if Americans were getting their money’s worth. But although drug companies, doctors, insurance companies, and hospitals are pulling in big money, the medical approach promoted by these interests is not necessarily helping people get well. True health and healing require personal responsibility, fundamental support, and removal of obstacles to health.

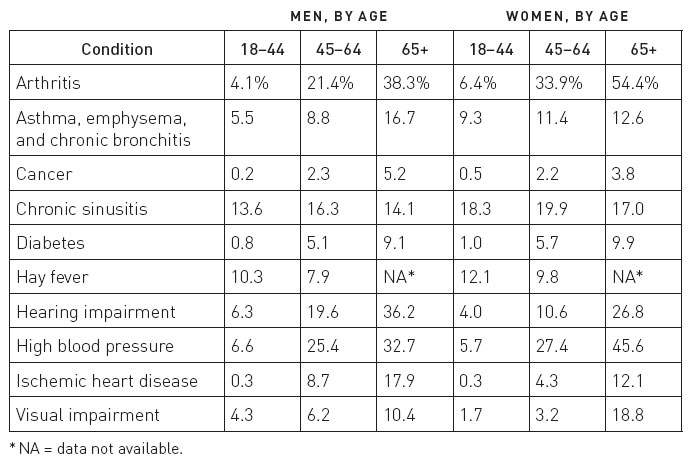

If the focus in medicine were on promoting health and wellness—if this became the dominant medical model—not only would health care costs be drastically reduced, but the health of Americans would improve dramatically. It is a sad fact that while we are grossly outspending every other nation in the world on health care, we are not, as a nation, healthy individuals. National health surveys have shown that almost half of all working Americans either have a serious chronic disease (arthritis, heart disease, high blood pressure, cancer, gallbladder disease, diabetes, rheumatism, emphysema, serious arteriosclerosis, and so on) or are in poor health. The health of their nonworking dependents is even worse: half to two-thirds of these adults suffer from chronic disease (such as cancer, diabetes, and heart disease) and generally poor health. What’s especially alarming about these statistics is that these are adults supposedly in their prime. The situation is worse for the elderly, virtually all of whom suffer from one or more chronic degenerative diseases.

Percentage of Adult Americans Suffering from the 10 Most Common Chronic Diseases22

WELLNESS-ORIENTED MEDICINE IS THE SOLUTION

Wellness-oriented medicine, such as naturopathic medicine, provides a realistic solution to escalating health care costs and poor health status in the United States. Equally important, this orientation can increase patients’ satisfaction. Studies have observed that patients who take the natural medicine–health promotion approach are more satisfied with the results of their treatment than they were with the results of conventional treatments such as drugs and surgeries. A few studies have directly compared patients’ satisfaction with natural medicine and patients’ satisfaction with conventional medicine. The largest study was done in the Netherlands, where natural medicine practitioners are an integral part of the health care system. This extensive study compared satisfaction in 3,782 patients who were seeing either a conventional physician or a “complementary practitioner.” The patients seeing the practitioner of natural medicine reported better results for almost every condition. Of particular interest was the observation that the patients seeing the complementary practitioners were somewhat sicker at the start of therapy, and that in only four of the 23 conditions did the conventional medical patients report better results.

Patient Satisfaction with Complementary Practitioners Compared with Medical Specialists

|

Symptom |

Complementary Practitioner, Patients Improved, Percent |

Medical Specialist, Patients Improved, Percent |

|

Palpitations |

63 |

59 |

|

Stiffness |

67 |

54 |

|

Feeling very ill |

75 |

78 |

|

Itching or burning |

71 |

50 |

|

Tiredness or lethargy |

70 |

60 |

|

Fever |

86 |

100 |

|

Pain |

70 |

58 |

|

Tension or depression |

69 |

65 |

|

Coughing |

76 |

50 |

|

Blood loss |

100 |

100 |

|

Tingling, numbness |

59 |

40 |

|

Shortness of breath |

77 |

53 |

|

Nausea and vomiting |

71 |

67 |

|

Diarrhea and constipation |

67 |

50 |

|

Poor vision or hearing |

31 |

47 |

|

Paralysis |

80 |

67 |

|

Insomnia |

58 |

45 |

|

Dizziness and fainting |

80 |

53 |

|

Anxiety |

65 |

64 |

|

Skin rash |

58 |

50 |

|

Emotional instability |

56 |

63 |

|

Sexual problems |

57 |

57 |

|

Other |

75 |

56 |

FINAL COMMENTS

In communicating with patients and my audiences I have learned that people process new information by asking themselves the question “What does this info have to do with me?” What I have done in this chapter is raise the issue of trust. In the forthcoming chapters, I will give more specific examples of why we should not be led blindly into using drugs or undergoing surgery without first asking some important questions:

What is the real benefit of taking this drug?

What are the risks of either taking or not taking the drug?

Are there any effective alternatives?

I also want to point out that although we all have some common characteristics, we also have our own unique biochemistry. Unfortunately, what might be a great medicine for one person might not work for or may even cause harm in someone else. Biochemical individuality is discussed in more depth in Chapter 11.