4

movement

Flight was an insect innovation—insects were the first fliers on Earth and are one of only four animal groups ever to have evolved the ability to self-propel through air. Their other means of locomotion are no less impressive—among their numbers we also find sprinters, leapers, climbers, water-treaders, and deep-divers.

The jointed legs and articulated bodies of insects allow them great freedom of movement to run, climb, leap, and fight.

muscular system

Insects are capable of some truly jaw-dropping physical feats relative to their body size, thanks to an array of efficient muscles with a very high energetic output.

From the weight-lifting abilities of ants and beetles to the prodigious leaps of fleas and grasshoppers, insects pack a lot of power into their small bodies. Muscles are not only used to drive the legs and wings, mouthparts, and antennae, but they also help push fluids through the body and push food through the digestive tract.

All insect muscle is of the type known as striated, because of its banded appearance visible under the microscope. It works by contraction (shortening). For example, the muscles that attach the top of a leg to the underside of its thorax segment will move that leg as a whole unit when they contract. There are also muscles attaching the body-segments to each other, which allow legless insect larvae to wriggle along through a squeezing and stretching action.

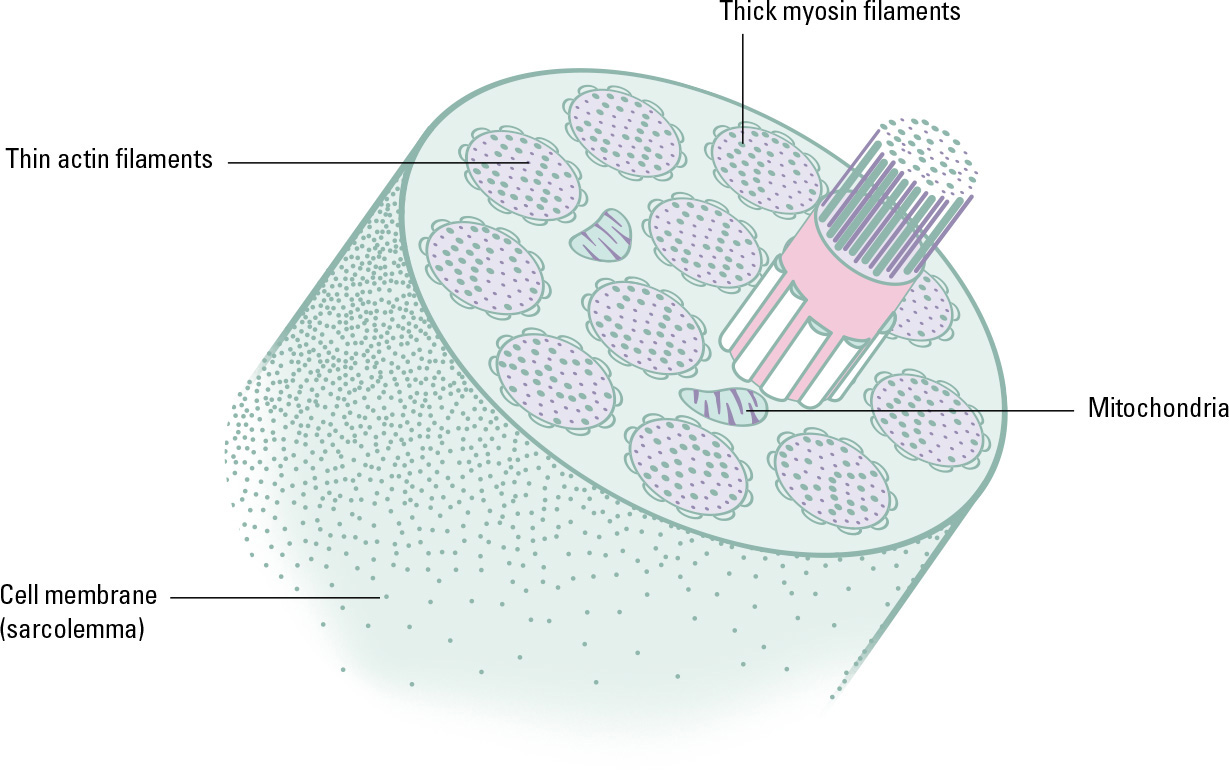

An individual muscle is made of several bundles of long, fibrous muscle cells (myocytes). Within the myocyte are alternating clusters of two types of protein filaments—actin and myosin—which are held together by chemical bonds. When the myocyte receives stimulation from a neuron, this causes a chemical change inside the myocyte that breaks the bonds holding the actin and myosin filaments to each other. When the bonds break, the filaments slide over one another, causing the myocyte to shorten in length. Because this occurs across all of the myocytes in the muscle, the entire muscle contracts.

A muscle cell, or myocyte, shows an organized structure, with the elongated filaments all collected together into bundles and functioning as a single unit.

Worker ants are expert at fetching and carrying, and can lift remarkably heavy loads.

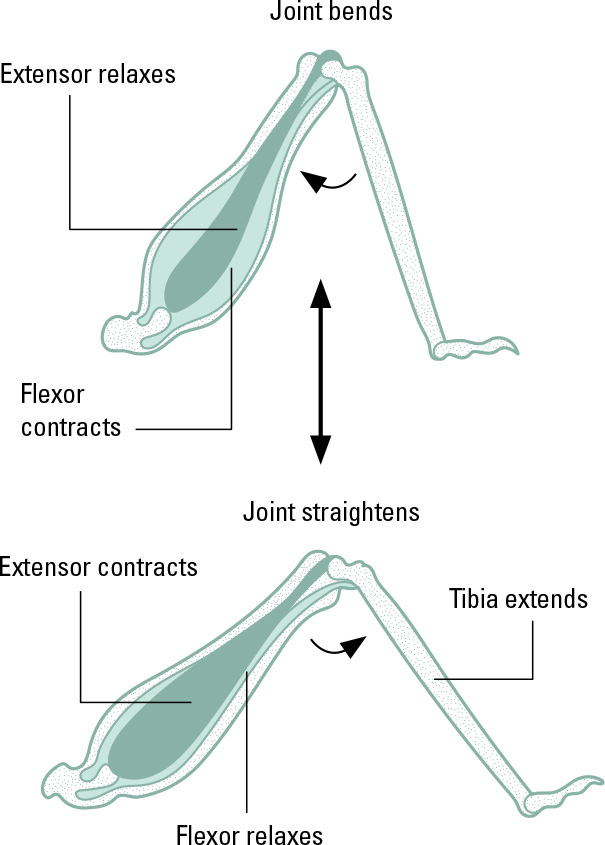

Contraction of flexor muscles causes the joint to bend, while contraction of extensor muscles straightens it.

flexing and straightening

Muscles to move a leg joint come in pairs, as is the case with our own muscles. The joints work like hinges and only bend one way. One end of each muscle attaches to each of the two segments either side of the joint. The muscle on the inside of the natural bend is an extensor—when it contracts and shortens it makes the joint straighten. The other muscle is a flexor—its contraction causes the joint to bend.

movement on land

Many insects—including the beetles, the most successful and diverse of all insect groups—get around on foot. Leg propulsion includes walking, scuttling, climbing, and leaping.

Insects with prominent strong legs are likely to be walkers or climbers, or they may use their legs to hunt, or to cling to difficult perches. The tiger beetles (subfamily Cicindelinae), which chase down and kill other insects on the ground, are among the fastest runners of all land invertebrates, with Cicindela hudsoni of Australia able to race along at 5.6 mph (9kph). The larger cockroaches are also fleet-footed, with Periplaneta americana able to reach 3.4 mph (5.5kph). Insects that are runners (cursorial) tend to have long legs with sturdy femurs, and the tarsi are tipped with strong claws for grip. The hind pair are longest but the middle and front legs are also substantial.

The most efficient running gait is “tripod,” with three feet in contact with the ground at any moment (the fore- and hind-legs on one side and middle leg on the other). This same gait is used when climbing a vertical surface. However, it has been observed that cockroaches can increase their running speed by taking alternating strides with all three legs on each side.

Grasshoppers and crickets have adaptations to their hind legs to power their leaps. The hind leg is much longer than the others, with an oversize femur to power the strong muscular contraction that fires them forward. They are generally slow and awkward on their feet when moving through vegetation.

Most beetles are adapted mainly for walking, running, or climbing, while grasshoppers are slow on foot until they leap.

Some grasshoppers can leap more than 200 times their body length.

sticking around

A housefly can easily perch and walk upside down on a ceiling, as well as vertically on a glass windowpane. Many other insects are capable of similar gravity-defying feats, thanks to anatomical tricks (coupled with their very low body-weight). It’s tempting to assume that they have suckers on their feet, but in the case of flies the grip is provided by masses of tiny setae (hairs) on the underside of the tarsus tip, which grip on to equally tiny ridges and fissures on the apparently smooth surface. Some other insects also secrete a sticky substance from their feet to aid the grip provided by the setae.

Flies can perch upside down with ease, even on quite smooth surfaces, thanks to the hairs on their feet.

The setae-covered pads on a fly’s foot help it hang onto smooth surfaces, while the curved claws can be used as prying tools to help it “unstick.”

flight

Insects have been on the wing for 400 million years. Their flight both impresses and baffles us, because its mechanisms and underlying anatomy are so different from those involved in vertebrate flight.

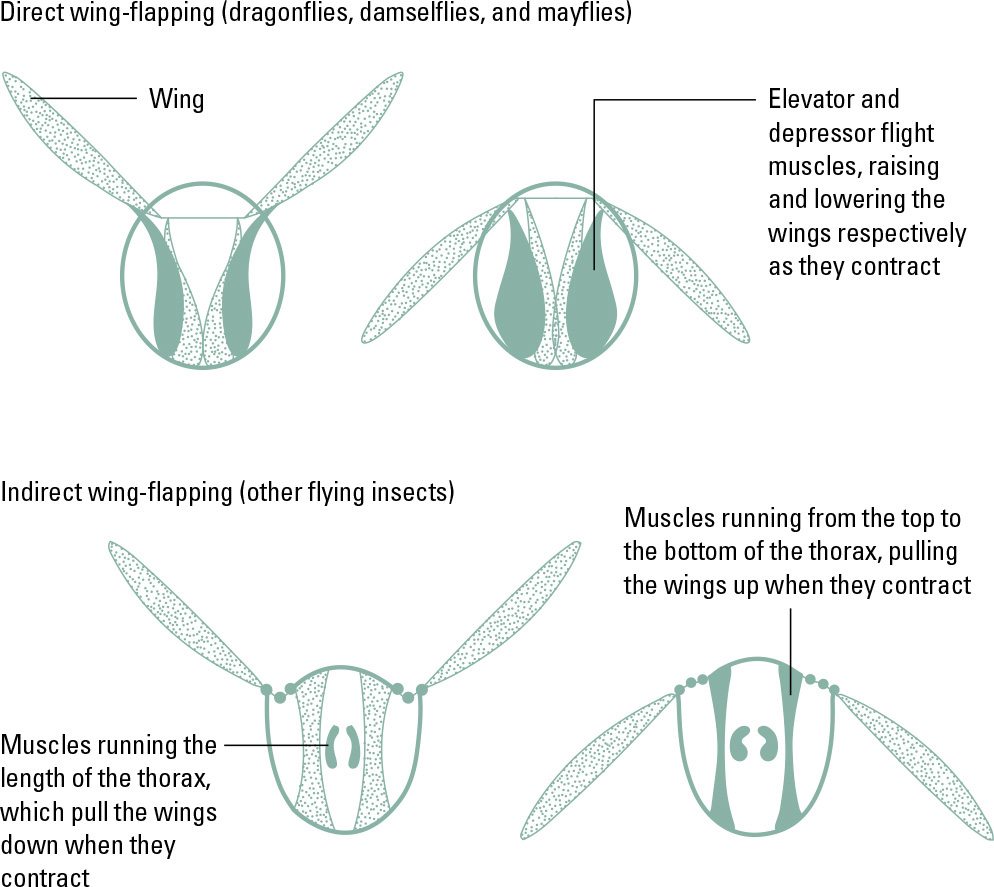

Insect flight muscles are attached to the base of the thorax. The upper attachment point may be the bases of the wings themselves, so the wings move up and down as the muscles relax and contract (top), or to the top of the thorax, so the wings move as a result of the thorax itself flexing and expanding with the muscular contractions (bottom).

Birds flap their wings by using muscles that connect their chest to the “upper arm” bones in their wings. In most insects, though, the flight muscles do not attach directly to the wings at all. Dragonflies and damselflies do have flexor and extensor muscles in their middle and hind thoracic segments that are connected to the bases of the wings. Each pair of wings can be moved independently, which gives these insects great control and maneuverability in the air. Mayflies also have flight muscles stretching between the thorax and the wings.

In most other flying insects, wing-flapping is achieved indirectly, through muscles within the thorax, attached to the upper-side and underside of the segments. As they contract and lengthen, the muscles distort the shape of the entire thorax, which causes the wings to move. This oscillating action is fast enough to drive wingbeats as rapid as 62,760 a minute (in the case of some Diptera species). There are tiny muscles within the wing as well, which alter its angle of attack.

It is often stated that bumblebees are “scientifically” incapable of flight, because they are too heavy for their small wings to lift them. This (demonstrably wrong) idea assumes that insects fly with up–down wingbeats. In fact, the flight stroke is more circular and involves the wings pushing forward, front-on, then tilting over and pulling back with the full face of the wing against the air. The action also generates tiny vortices (like tornadoes) in the air above the wing, which reduces air pressure, helping the insect overcome its own weight.

Many species of hawkmoth are expert at hovering, using this ability to feed from flowers that would not support their weight.

Some insects, including many moths, have a coupling mechanism that holds the front and hind wing on each side together, so that they function as a single pair. This improves energy efficiency, though makes for a less agile flight than for insects with independently moving wings. The way the wings fix together varies—in some cases there is a hook and corresponding notch, in others the wings are not physically attached but the forewing overlaps the hind wing, which holds them together on the flight downstroke.

clap and fling

Some very small flying insects, such as thrips, use a very different technique to become airborne. They clap their wings together above their backs, and the downward rebound creates a vortex over each wing that sucks the insect upward. This flight method is known as “clap and fling.” Because its action is quite violent and can quickly cause damage to the wings, the technique is most often seen in insects with short adult life spans.

Thrips are among the few insects that fly though a rather violent “clap and fling” action.

swimming and diving

Many insects live in water in their larval stages, and some, such as water beetles and water boatmen, remain water-dwellers as adults—even though they are also capable of flight.

Although insects’ ancestors were thought to be marine and freshwater crustaceans, the rather small number of insects on Earth today that are aquatic as adults have evolved from terrestrial ancestors. Aquatic adult insects belong to two major groups, the beetles and the true bugs, whereas most other members of these groups are landbound in all their life stages. Insects that are aquatic only as larvae are more diverse. They include mayflies, stoneflies, dragonflies, caddisflies, and some true flies, lacewings, and moths.

To live in water doesn’t necessarily require an insect to swim—it may walk on the substrate, or clamber in underwater vegetation. However, some insects are true swimmers and divers, and possess modified leg anatomy to propel them through water. In most cases, this involves a dense unidirectional “paddle” formed by setae (hairs) on one or more of the leg pairs. In the whirligig beetles (family Gyrinidae), the middle and hind legs are short and flipper-like, while the front legs are long and used for seizing prey rather than swimming. In most cases, water beetles’ swimming legs work together rather than alternately.

Among the water boatmen (family Corixidae) and backswimmers (family Notonectidae), both of which are true bugs (Hemiptera), the hind legs are elongated and fringed with hairs. These legs act like oars to move the insect through the water.

Swimming insects such as backswimmers (left) and diving beetles (right) propel themselves by using their legs as paddles or oars.

Some water insects only swim on the surface, but diving beetles have good enough propulsion to dive deep underwater. They overcome the other challenge of subaquatic life—the need for oxygen—by carrying a supply of it with them. They capture a bubble of air under their elytra and breathe from it as they swim. The bubble can also partly replenish itself, as some of the dissolved oxygen in the water will diffuse into it, making it a functional gill. Other swimming beetles and bugs have a layer of breathable air trapped in hairs on their exoskeleton—known as a plastron, these can in some cases supply them with a lifetime of air, meaning they need never surface.

A pond skater’s feet dimple but do not break the water’s surface tension.

Bubbles caught in the body hairs provide swimming beetles with an underwater air supply.

walking on water

Pond skaters or water striders (family Gerridae), and some other water bugs live on rather than in the water. By distributing their tiny body-weight over a wide area, these long-legged insects are supported by the water’s surface tension. The tips of their tarsi are covered in waxy hairs that trap tiny air bubbles, providing buoyancy.

escaping danger

Some kinds of insect movement are only deployed at times of necessity. When danger threatens, it’s helpful to have a “special move” that can get you out of trouble in a hurry.

A huge array of animals prey on insects—including other insects. Even the most formidable dragonfly or hornet will probably end its days prematurely, as lunch for a bigger hunter. But many insects have ways to try to physically escape from danger, beyond simply fleeing as quickly as they can.

The click beetles (family Elateridae) do not have the legs of a specialized jumper, but they can leap nonetheless. They can run and scramble perfectly well, but if they are knocked on their back they can only right themselves by “clicking”—and the same move can help them escape a predator. The front segment of the thorax has a small projection at its rear. When the insect flexes its body swiftly and strongly enough, this projection is locked into a corresponding notch on the second thoracic segment. The recoil force propels the beetle into the air with an audible click. It may turn several somersaults before landing some distance away and (with luck) the right way up.

Some moths and butterflies use “startle coloration” to try to dissuade predators from attacking them. The Eyed Hawkmoth (Smerinthus ocellata) has colorful eyelike markings on its hind wings. It rests with the forewings covering the hind wings. If it is attacked while at rest, it uses its wing muscles to move the front wings forward rapidly. This flashes the hind wing “eyes” and hopefully distracts the predator.

Many predators will lose interest if their prey appears to suddenly drop dead.

A click beetle’s spring is provided by the hinge on its first thoracic segment snapping into a notch on the second segment.

Click beetles are capable of flight, but their clicking mechanism allows for a much faster escape.

playing dead

Many foliage-dwelling insects, if disturbed, will release their grip and fall limply to the ground, hoping that the leaves will hide them wherever they land. If they have fallen as far as they can and the potential predator is still interested, they may continue to “play dead” for a long spell. This is effective self-defense, as predators only attack live prey. Some ground-dwelling insects also play dead very effectively—certain beetles of the family Tenebrionidae (the darkling beetle) are known as “death-feigning beetles,” so readily and effectively do they take on a lifeless appearance.

immobility

The class Insecta includes some of the world’s most well-traveled migratory animals, but there are also some insects that, from hatching to death, barely move at all.

Animals that do not move are known as sessile. Many of them begin life as highly mobile—for example, the acorn barnacles that encrust shoreline rocks start out as free-swimming larvae, before they find a place to settle in the intertidal zone and secrete the calcified plates that surround them and hold them in place for the rest of their lives.

There are few truly sessile insects. Scale insects (superfamily Coccoidea) do qualify, or at least the females do. These usually very small members of the true bug group feed by sucking the sap out of plant stems with their piercing mouthparts. They are mobile on hatching, but after their first few molts the wingless females become fixed to one spot, feeding continuously, and typically secrete a thick shield of wax for protection. Males usually do have wings on maturity, enabling them to find and mate with females. Some scale insects are guarded by ants, which gather the honeydew they excrete. The ants may even move young scale insects around their host plant, to suitable feeding spots.

The females of several species of moths are flightless and almost immobile. The female Vapourer Moth (Orgyia antiqua) has a very distended abdomen and reduced, stumpy wings. When she emerges from her pupa, she releases pheromones that attract males, and after mating she lays her large clutch of eggs on and around the silk cocoon that had protected her while she was pupating. Vapourer caterpillars are very mobile and active, and make the most of this ability to find a safe site to pupate where they will be able to complete their life cycle away from predators.

Ladybugs’ bright coloration warns of their distasteful bodies and discourages predators from attacking them.

A female Vapourer Moth is far more active as a caterpillar than it will be once it reaches its adult phase.

motionless survival

Even the most active insects may spend hours or days motionless, under certain conditions. In temperate parts of the world, many adult and larval insects pass the coldest months in a state of hibernation. With drastically slowed metabolism, they conserve their energy so that they can resume activity when the temperature rises. Even in midsummer there may be sustained days of rain or low temperatures, forcing them to become inactive. This is why even highly active insects generally have good camouflage, or if not they have highly unpalatable bodies and exhibit bright coloration to warn of this—enforced immobility is a part of life for them.

Mealybugs and other scale insects feed by sucking fluids from plant tissue, and many species barely move throughout their lives.