23. Family Practice Evolves in Rochester

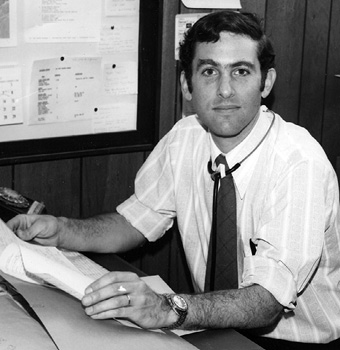

It was the 1970s. We thought we could do anything. Here I was, CEO and medical director of an organization that I had started. I knew nothing about administration, finance, community organization. Never mind. Surrounded by people with a similar “just do it” bent, we somehow managed to get the centres up and running, providing services to communities in need.

Since I had made the decision to use a family medicine model, rather than the multi-specialty group practice model that I had personally experienced and rejected, I thoroughly enjoyed the transition from pediatrician to family physician. Surrounded by the family physicians that I had hired for the three health centres, I continued to strengthen my skills as a family physician.

Family medicine really fit the needs of my patients and was a source of the human drama that I appreciated. I loved the stories. Caring for the entire family provided insights that caring for individuals could not. It was clear to me that I had been destined to be a family physician, and probably would have trained as one from the start, if only I had seen one as a medical student. Role models again.

Because of my large administrative load, I could not have a full-time practice, so I decided that I would only take on whole families. Although this occasionally created problems for individuals who needed privacy from family, perhaps 90 per cent of the practice was truly full family practice.

In the development of the health centres, I worked closely with Dennis Spain, a young graduate of the community dental program at the University of Rochester. A creative dentist, not formally trained in dental surgery, he nevertheless did lots of dental surgery, while also designing and building most of the dental equipment. We were developing our organizational skills along with our clinical practices. It was a bit nuts, and we were bound to make mistakes, as we were untrained for the hurly-burly of complex community issues.

Caring for patients at various financial levels was difficult. At Westside Health Services, we had a good contract with the county Health Department for the care of poor people on Medicaid, with a good reimbursement rate for each visit. People on Medicaid were on welfare, having gotten there by virtue of poverty or even severe illness leading to poverty—still a basic feature of the American health care system. We also had good contracts with Blue Cross Blue Shield for enrolled families working at Kodak, Bausch + Lomb, American Optical, et cetera. This was during the early days of health maintenance organizations (HMOs), now called Managed Care Organizations. But we had another group as well, those we called the marginal poor or sometimes employed. We billed them for their visits and care but rarely got paid.

So we “borrowed” from the county and Blue Cross Blue Shield to try to float the care for the uninsured. Ultimately, it cannot be done and was eventually doomed. Such an impossible task loomed large in my eventual decision to return to Canada, where a single-payer system makes it possible to care for all without reference to their ability to pay. In 2018, the hungry American multinationals and private facilities are salivating at the potential Canadian market, if only they can gain access under the free trade system.

Caring for so many patients without insurance was problematic. I remember looking into the mouth of a poor Black woman and finding a serious cancer behind her upper molars. I went downstairs to consult with Dennis, who confirmed my diagnosis. She needed major oral surgery and could not pay for it—one of the joys of the American medical system. Dennis implored an oral surgeon he knew to operate for free, which he did, but the woman was left with a huge hole in her pallet so that her speech was embarrassingly nasal. Payment for the needed reconstructive surgery was out of the question. Dennis, ever creative and without surgical experience with such a problem, acted as we both did in those early days: flying by the seat of his pants.

He hit the books, learned about plastics and constructed a false palate, to which he attached some prosthetic teeth. Problem solved. This was the paradigm for much of our work in those early days. I was not trained in administration and he was not trained in oral surgery, which he nevertheless began doing with great success. Dennis later, without a degree in oral surgery, became head of oral surgery in a California facility.

Meanwhile, I began to find the dual role of executive director and medical director burdensome, especially as I was morphing into a family physician in my personally designed family medicine training program, which took considerable time and energy. Bonnie reminded me that this was the time when the feminist revolution was in full swing. It was a time of consciousness-raising groups and experimentation with open marriage. Alone at home with two small kids and a job that could not replace the wonderful NFB, Bonnie joined a discussion group in our graduate student housing complex made up of women with small children and husbands doing graduate work.

We had our marital tensions, largely because of my workaholic focus on the developing health centres. But the dissolution of my early marriage made me determined to save ours. Bonnie recalls that our marriage was the only one of the eight in her consciousness-raising group that survived.

I was determined to reduce my workload. After consulting Dennis, my partner in crime, and with reluctance at leaving the overall leadership of the centres that I had created, I decided to recruit an executive director so that I could focus only on medical issues as medical director, while continuing to hone my family practice skills by seeing family practice patients.

The community board that I had developed and trained was representative of the three communities using the three health centres, with a wonderful mix of ethnicities and races. Board meetings were often charged with local politics, which we were learning about as we went along. Working with the community board, it was a great relief to recruit a personable young new graduate from a business school as executive director. He was Black and comfortable with a good deal of the politics of the neighbourhood health centre movement in the 1970s. Finally, I was no longer expected to attend board meetings, except to report on my role as medical director.

Our Neighbourhood Health Centres at Risk

After two years of the new CEO’s reign, Tania, the finance clerk, whom I had known since the early days when I was just developing the network, approached me, concern on her face, asking me to please have a look at several monthly financial statements. I was reluctant, as this was no longer my area of responsibility. She insisted. Even a cursory look made it clear to me that the financial picture was deeply troubling. Unless we did something drastic, the health centres would be insolvent within three months. Tania also had some ideas about where some of the money had gone. I sought confirmation from Dennis, who also looked at the books. On top of the financial discrepancies, there were other personal shenanigans going on between the new leadership and certain board members. As it was no longer my responsibility, I tried very hard to ignore what I knew was going on at that level. What to do? What was our responsibility to the network that we had worked so hard to develop? To be fair, neither Dennis nor I had anything to lose. We each were nearing the end of our employment in Rochester. I had a new job waiting for me in Montreal and he in California. Regardless, we both felt a deep responsibility to protect the health centres and the communities they served.

The operating certificate for the health centre network was held by the New York State Health Department. Only they had the power to fix the situation, if it was even possible to fix it. We decided that the only thing to do was notify the Health Department of what was going on. They would have the power to fire the executive director and the community board, put the network into receivership and take over running the health centres.

We knew that the community board would have to fire us if we contacted the Health Department over their heads, but that was a small price to pay. So the next morning we called the New York State Health Department and detailed the situation, urging them to come in urgently, take over and save the health centres. Then we notified the board and executive director of our actions and, as expected, were fired on the spot.

While Dennis and I were packing up our things, the New York State board came in rapidly and fired the community board and the executive director, took over our network and saved the health centres. The whole story can be found in the administrative case studies at the Sloan School of Management at MIT in Cambridge. What a way to be famous.

I last visited Rochester in 2009. Two of the three centres were still running and doing well. One of my old patients, who was a nurse, was now the director of one centre. It felt good. At a recent meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group, I noticed the label Westside Health Services: Brown Square, one of the three original centres, on the lapel of a young family physician presenting a paper at the meeting. I introduced myself. “Oh, you’re Michael Klein. I’m using some of the health education pamphlets you wrote way back in the 1970s.” Did she know anything about the saga of the centres and my firing? No, she did not. Organizational memory is thin.