30. Birth: Why Do This Work When It Sounds So Exhausting?

By the mid-1980s, our birth practice at the Jewish General Hospital had become well established, and our maternity group was active in practice and teaching. Bonnie says that when I came home from a birth, I always looked exhilarated. And I felt that way. A birth is a life-affirming event, no matter how long it takes, no matter if it happens in the middle of the night, no matter how disruptive to my life and practice. It is sometimes a good excuse not to go to an administrative meeting that I did not want to go to in the first place.

Bonnie says that even when the phone call in the middle of the night disrupted her sleep, she experienced a contact high. In birth I see women and partners having an existential, often ecstatic or orgasmic experience. They overcome pain and an exhausting event that brings them closer to their partner and caregiver, and transforms them forever. I never cease to be moved by the power of women, and no matter how many births I have attended (about two thousand), I continue to wonder how women manage to get through it.

When I attend a birth, and then a woman’s second or third birth, when I meet the children I have delivered and especially when I attend a woman whose own birth I attended, I experience a long-lasting and powerful joy. A most extreme satisfaction occurs when a mother whose birth I attended comes for prenatal care with her pregnant daughter. For a practitioner, attending a joyous birth is an antidote to balance the care of patients with cancer or who are approaching death.

It was time to apply the birth research I had done in Oxford to Montreal. Given my background as a neonatologist/pediatrician and family physician, I often found myself working at the interface of the various disciplines involved in birth. It was logical that one of my first post-Oxford research projects should be about birth.

As the hospital was developing its first birth room, I saw an opportunity to study its impact. We decided to do a randomized controlled trial of the new birth room compared to our hospital’s traditional or conventional care. To make sure that I was on the right track, I went to Cleveland to consult with Dr. Marshall Klaus, the doctor who I first met as a medical student whose big-picture approach to mother and infant care I was developmentally unprepared to understand at the time.

As always, I shared my work with my own family. One of the outcomes that I had planned to use involved a newborn neuro-behavioural exam undertaken in the first few minutes of life in the two settings: the birth room versus the conventional setting. One night, as I was sharing the design over dinner, Seth, at age fifteen, said: “The world is on the verge of nuclear destruction, children are starving and you are studying the first few minutes of life? Why don’t you study something important?” I dropped that measurement.

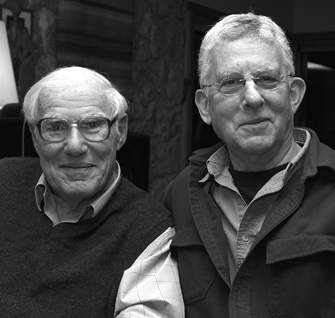

Thinking back on this comment, for me it presages Seth’s critical thinking and his current role as founding director of the BC office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA-BC) in Vancouver. He has continued in this role for more than twenty years. His thoughtful comment on my research fits well with his current work on climate justice, reducing poverty, establishing a living wage and improving the lives of those at the margins.

We thought that the birth room might have a number of positive results for the mother and newborn. However, the results were at times anomalous. In the birth room, the father tended to fall asleep or read the newspaper in the nice double bed, but if the mother was allocated to the conventional setting, the father was on guard to protect the mother from the perceived dangers of a medicalized setting. The birth room was the preferred setting. Our research showed some benefits for the mother in the birth room, compared to the conventional setting, in the form of some reductions in procedure use. Paradoxically, it appeared that the father in the conventional setting had a more positive relationship with the newborn than in the birth room, and this effect lasted for a year. It seemed that the protective behaviour of the father in the conventional setting fostered a more lasting attachment to the newborn.7 Then we found that births in the birth room appeared to be associated with fewer admissions to the newborn ICU, a big result that turned out to be wonky. What really happened was that in the conventional setting, if the newborn was not pink and perfect, he was whisked off to the ICU, needed or not. In the birth room, babies in similar transitional or temporary states were handled differently. In that setting caregivers would tend to stimulate and play with the newborn as the transitional state resolved. All newborns did well, regardless of setting. Overall, it was clear that the birth room did indeed change behaviour, but most importantly couples experiencing the birth room were more positive about their experience and would repeat it in a subsequent birth.