31. Caring for the Religious Jewish Community of Montreal

One day a very distraught young Orthodox Jewish woman appeared in the office. She had almost continuous vaginal spotting. I examined her and found that she had a small erosion on her cervix. This is a minor problem, easily resolved by cauterizing the areas of the cervix that are bleeding.

Having sexual intercourse is an obligation in that religious group, with women required to have lots of children, sometimes up to ten or twelve children. It is not unusual for women in this community to be having babies well into their forties. But spotting is also a big issue in that community because a religious dictum prevents sexual intercourse during bleeding. Moreover, when bleeding stops, even briefly, the woman has to go to the mikveh (the ritual bathhouse), where she is ritually cleansed and made ready for intercourse. Many times per month, this poor woman was running between home and the mikveh, becoming exhausted and depressed. But I was not permitted to do the needed resolution without permission from the rabbi. What was critical was that it was clear that the bleeding came from the cervix and was not menstrual bleeding. The prohibition of intercourse while bleeding pertained only to bleeding from the womb. When I explained this distinction to the woman, she asked me to contact her rabbi to explain her dilemma.

I called. An obviously older man answered in a heavy Eastern European accent that was a bit hard for me to understand. I explained the problem, and the distinction between the blood flowing from the cervix and the menstrual blood flowing from the womb. There was a long pause while he considered the problem. It was news to him, so, surprisingly, he asked me to fax him a picture. I did. The picture showed the location of the bleeding and my plan to resolve it. I received permission to proceed.

A more grateful patient is hard to remember. But that one case led to an avalanche of other patients from the religious Jewish community. When we eventually left Montreal for Vancouver, my colleague and friend Dr. Perle Feldman took over the care of this community. In Vancouver, I applied the same approach to some issues in the Muslim community. Some Muslim women felt uncomfortable having their birth attended by a male doctor. Our birth group was a mix of male and female family doctors. At first we honoured the request for a female birth doctor, but in time this became too hard on the women in our call group—as they needed to be on duty not only when taking their turn but also in a secondary call group for Muslim women’s births. What to do? I called the local imam and explained the problem. He authorized his congregation to have male birth attendants when needed.

A Strange Role

Circumcision is performed among Jewish newborns because of a biblical command to do so. A ritual accompanies it, in which the mohel (ritual circumciser) performs the surgical procedure of removing the foreskin, and there is much rejoicing (not by the baby) and some food, typically sponge cake. In general, I discouraged the procedure, as the evidence shows it is not needed and complications do infrequently arise. It was extremely rare for a circumcision to be needed in an older uncircumcised child or adult because of complications of infection or urinary obstruction. There continues to be a debate about the pros and cons of the procedure, with national pediatric organizations giving contradictory recommendations.

Perhaps two thousand years ago in the desert it was a useful procedure. One can imagine that getting some sand under the foreskin could be a problem. But in modern society, in my opinion, there is no longer any scientific justification for the procedure. The ritual continues because of the history and biblical requirement, and as a way to distinguish being Jewish from other societal and ethnic groups.

The Montreal ritual circumcisers were under the control of the city’s chief rabbinical authorities. Thus, although I worked at the Jewish General Hospital, I had no role in doing circumcisions for Jewish families. When non-Jewish couples in my practice insisted on circumcision, or even when other doctors would send their patients to me for the procedure, I would try very hard to change their minds. If I failed to persuade them, I would do the procedure, using the same simple tools as the mohels. My practice was to give the newborn some ritual wine on cotton in a bottle nipple. I kept a bottle of Manischewitz, the official, very sweet sacramental kosher wine in my desk drawer. Then, unlike the mohels, I did a nerve block on the newborn penis. Usually, the baby slept through the procedure, rather than screaming in pain. Doing the procedure without local anaesthesia, in my opinion, is barbaric. News travels fast. I developed an unwanted circumcision practice.

But there was a special group for whom I had a particular affinity: couples who were of mixed religion. Generally, the father was Jewish and the mother was not. Since Jewish identity is matrilineal, the rabbinate refused to allow the mohels to officiate in the procedure for such mixed marriages. For those couples, frantic to find someone to do the procedure, I felt an obligation. But not being a religious Jew, I felt it was inappropriate for me to conduct the religious ceremony that accompanies the procedure. For that reason, I joined forces with my own rabbi, Ron Aigen, who would do the religious part while I was a sympathetic technician. After a while, my rabbi got tired of that role and taught me a minimal ceremony that he assured me was adequate, as he explained that even the father could do it if necessary.

Too Well Known

A pregnant Jewish couple entered the practice. They had a ten-year-old girl from a previous marriage. In their previous lives, they were not very religious. They each had experienced a birth in their prior non-religious lives, and in that previous birth, the father was deeply engaged and hands on with the labour, massaging his labouring partner and otherwise supporting her. Things had changed. The father was now also a rabbi and a Hebrew school teacher. They both wanted the intimacy that they had experienced before, but the rules of the very religious group that they had now joined forbade the presence of the father after the wife’s water had broken. At that time, she was considered religiously “unclean.” I told them I would think of what to do.

A couple of weeks later, the same elderly rabbi who had okayed me to cauterize the cervix of the patient with continuous vaginal spotting was on the line. Without even a hello, he said: “Doctor, how can it be that a woman would need to be touched during labour?” I knew what he was driving at. It could only be a result of the desires of the recent couple.

I told him that touching could be beneficial, shortening labour and even leading to a better labour outcome. There was a very long pause.

“What about the baby?” he inquired

“There could be a better outcome for the baby and the mother,” I answered.

There was a long pause while he digested the information.

I finally asked, “What are we deciding?”

The rabbi said, “We are deciding that you are deciding.”

The rabbi had invested me with the religious authority to act on his behalf in this situation. I understood, but given my lack of religious attachment, I felt like a fraud.

On the next visit, the couple inquired if the rabbi had called. Yes, he had called and invested me with the power to make a determination as to the need for touching. In the Jewish religion, the health of the baby trumps everything. Without realizing it, I had said the magic words: “better outcome for the baby.”

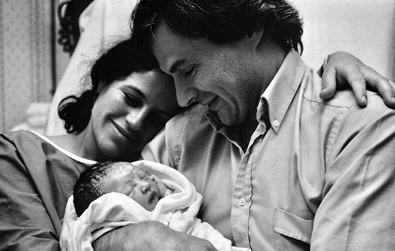

Several weeks later, the woman went into labour. The father was pacing the hall and reading from the Bible. The woman was beginning to be distressed by the pain. “Is it time yet?” she asked. “It’s time,” I said. I invited the father to come in to give hands-on support. All went well.