In This Chapter

Understanding breathing basics

Understanding breathing basics

Detailing yogic breathing mechanics and techniques

Detailing yogic breathing mechanics and techniques

In the ancient Sanskrit language, the word for “breath” is the same as the word for “life” — prana (pronounced prah-nah) — which translates into what is known as vital force, your life force. This gives you a good clue about how important yoga thinks breathing is for your well-being. Yoga practiced without conscious breathing (which awakens prana) is like putting an empty pot on the stove and hoping for a delicious meal.

In this chapter, you discover how to use conscious breathing in conjunction with the yoga postures. This chapter also introduces several breathing exercises that you do seated either on a chair or in one of the yoga sitting postures (if you’re up to that).

Breathing Your Way to Good Health

Most people’s breathing habits are quite poor and to their great disadvantage. Shallow breathing, which is common, doesn’t efficiently oxygenate the ten pints of blood circulating in your arteries and veins. Consequently, toxins accumulate in the cells. Before you know it, you feel mentally sluggish and emotionally down, and eventually organs begin to malfunction. Poor breathing is also known to cause and increase stress, which itself shortens your breath and increases your level of anxiety.

You can help alleviate stress through the simple practice of yogic breathing. Among other benefits, breathing loads your blood with oxygen, which, by nourishing and repairing your body’s cells, maintains your health at the most fundamental level. Is it any wonder that the breath is the best tool you have to profoundly affect your body and mind?

The masters of yoga discovered the usefulness of the breath thousands of years ago and have perfected a system for the conscious control of breathing. In yoga, consciously regulated breathing has three major applications:

- In conjunction with the various postures, to achieve the deepest possible effect and to prepare the mind for meditation

- As breath control (called pranayama, pronounced prah-nah-yah-mah), to invigorate your vitality and reduce your anxiety

- As a healing method in which you consciously direct the breath to a particular part or organ of the body, to remove energetic blockages and facilitate healing

During your normal breathing, you may notice a slight natural pause between inhalation and exhalation. This pause becomes important in yogic breathing; even though it lasts only one or two seconds, the pause is a natural moment of stillness and meditation. If you pay attention to this pause, it can help you become more aware of the unity among body, breath, and mind — all of which are key elements in your yoga practice. With the help of a teacher, you also can discover how to lengthen the pause during various yoga postures to heighten its positive effects.

During your normal breathing, you may notice a slight natural pause between inhalation and exhalation. This pause becomes important in yogic breathing; even though it lasts only one or two seconds, the pause is a natural moment of stillness and meditation. If you pay attention to this pause, it can help you become more aware of the unity among body, breath, and mind — all of which are key elements in your yoga practice. With the help of a teacher, you also can discover how to lengthen the pause during various yoga postures to heighten its positive effects.

Practicing safe yogic breathing

As you look forward to the calming and restorative power of yogic breathing, take time to reflect on a few safety tips that can help you enjoy your experience:

- If you have problems with your lungs (such as a cold or asthma), or if you have heart disease, consult your physician before embarking on breath control, even if you’re under the supervision of a yoga therapist.

- Don’t practice breathing exercises when the air is too cold or too hot. Also avoid practicing in polluted air, including the smoke from incense.

- Don’t strain your breathing; remain relaxed while doing the breathing exercises.

- Don’t overdo the number of repetitions. Stay within the guidelines for each exercise.

- Don’t wear constricting clothing.

Reaping the physical benefits of yogic breathing

Besides benefiting your mental outlook, yoga breathing techniques offer many benefits to your health. Here are a handful of them:

- Metabolism: Breathing well supports the function of the digestive, respiratory, circulatory, and hormonal systems and may be helpful in promoting metabolic balance.

- Detoxification: When you exhale, you release carbon dioxide (a waste product of your body’s natural metabolism) that has been passed from your bloodstream into your lungs. By expelling air from the deepest recesses of your lungs, you expel more carbon dioxide and you enable your lungs to take in more oxygen.

- Oxygenation: The supply of oxygen to your brain and the muscles of your body increases. Oxygen enables your body to metabolize vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients.

- Organ massage: Each time you inhale, your diaphragm descends and your abdomen expands. This action massages your intestines, heart, and other organs near your diaphragm. Proper breathing helps to promote improved circulation in these organs. What’s more, it helps to strengthen and tone your abdominal muscles.

- Posture: The breathing techniques encourage good posture. Poor posture can be a cause of incorrect breathing.

According to the yoga tradition, each person is allotted a certain number of breaths, and after you exceed this number, your time on earth is finished. People who breathe hurriedly and shallowly use up their allotment of breaths quickly, but if you breathe slowly and consciously, your breath allotment lasts for many years. Let this thoughtful idea remind you how valuable and life-expanding each breath may be. Developing a breath that’s balanced, steady, and rhythmic — one that’s never forced but deep and full — helps you live a long and healthy life.

According to the yoga tradition, each person is allotted a certain number of breaths, and after you exceed this number, your time on earth is finished. People who breathe hurriedly and shallowly use up their allotment of breaths quickly, but if you breathe slowly and consciously, your breath allotment lasts for many years. Let this thoughtful idea remind you how valuable and life-expanding each breath may be. Developing a breath that’s balanced, steady, and rhythmic — one that’s never forced but deep and full — helps you live a long and healthy life.

Understanding the emotional benefits of yogic breathing

Psychologically, people tend to use the diaphragm as a lid to bottle up their undigested or unwanted emotions of anger and fear. Chronic contraction of the diaphragm makes it inflexible and blocks the free flow of energy between the abdomen (the nether region of the bowels) and the chest (the feelings associated with the heart). Yogic breathing helps restore flexibility and function to the diaphragm and removes obstructions to the flow of physical and emotional energy. You can then experience liberation of your emotions, which can lead you to integrate them with the rest of your life.

Deep breathing not only affects the organs in your chest and abdomen but also reaches down into your gut emotions. Don’t be surprised if sighs and perhaps even a few tears accompany the tension release your breath work achieves. These are welcome signs that you’re peeling off the muscular armor you have placed around your abdomen and heart. Instead of feeling concerned or embarrassed, rejoice in your newly gained inner freedom! Yoga practitioners know that real men (and women) do cry.

A Variety of Yoga Breathing Techniques

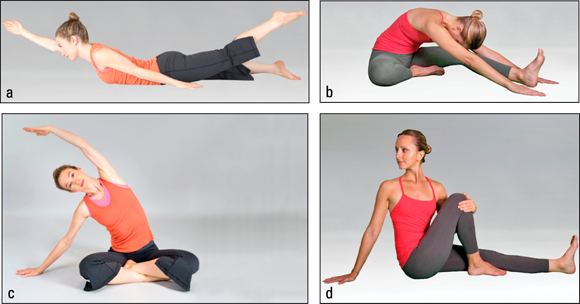

The breathing techniques presented here are designed to relax and energize you. You can practice these breathing techniques by themselves or as you do your yoga routines and workouts. Get to know each technique so that you can call on it when you need it. After experimenting for a while, you discover the breath that feels best to you while you’re working out. Although several workouts in this book offer a suggestion for a certain breath, feel free to substitute a breath you prefer. You can also do these breathing techniques while you’re sitting, lying down, or standing.

No matter which breathing technique you undertake, follow these basic breathing guidelines:

No matter which breathing technique you undertake, follow these basic breathing guidelines:

The Complete Breath

Most people are either shallow chest breathers or shallow belly breathers. Yogic breathing incorporates a complete breath that expands both the chest and the abdomen on inhalation either from the chest down or from the abdomen up. The Complete Breath engages your entire respiratory system. Besides raising and gently opening your collarbone and rib cage area, you engage your abdomen evenly and activate your diaphragm naturally, thus creating a full and deep breath. If you do no other yoga exercise, the complete yoga breath — integrally combined with relaxation — can still be of invaluable benefit to you.

Ideally, you should inhale and exhale six times per minute when using the Complete Breath. Breathing through your nostrils, you inhale four to six counts at minimum, and you exhale six to ten counts at minimum. Of course, this is the ideal, but if you’re new to yoga, inhale as many counts as you can without straining, and try to reach the four- to six-count minimum.

Yogic breathing involves breathing much more deeply than usual, which, in turn, brings more oxygen into your system. Don’t be surprised if you feel a little lightheaded or even dizzy in the beginning. If this situation happens during your yoga practice, just rest for a few minutes or lie down until you feel like proceeding. Remind yourself that you don’t need to rush.

Yogic breathing involves breathing much more deeply than usual, which, in turn, brings more oxygen into your system. Don’t be surprised if you feel a little lightheaded or even dizzy in the beginning. If this situation happens during your yoga practice, just rest for a few minutes or lie down until you feel like proceeding. Remind yourself that you don’t need to rush.

Belly-to-chest breathing

In belly-to-chest breathing, you really exercise your chest and diaphragm muscles as well as your lungs, and you treat your body with oodles of oxygen and life force (prana). When you’re done, your cells are humming with energy, and your brain is grateful to you for the extra boost. You can use this form of breathing before you begin your relaxation practice, before and where indicated during your practice of the yoga postures, and whenever you feel so inclined throughout the day. You don’t necessarily have to lie down as described in this exercise; you can be seated or even walking. After practicing this technique for a while, you may find that it becomes second nature to you.

-

Lie flat on your back, with your knees bent and your feet on the floor at hip width, and relax.

Place a small pillow or folded blanket under your head if you have tension in your neck or if your chin tilts upward. Place a large pillow under your knees if your back is uncomfortable.

- Inhale while expanding your abdomen, your ribs, and then your chest; pause for a couple of seconds.

-

Exhale while releasing your chest and shoulder muscles, gently and continuously contracting or drawing in your abdomen; pause again for a couple of seconds.

- Repeat Steps 2 and 3 from 6 to 12 times.

You can greatly enhance the value of this exercise and others by fully participating with your mind. Feel the air fill your lungs. Feel your muscles work. Feel your body as a whole. Visualize precious life energy entering your lungs and every cell of your body, rejuvenating and energizing you. To help you experience this exercise more profoundly, keep your eyes closed. Place your hands on your abdomen and feel it expand upon inhalation.

You can greatly enhance the value of this exercise and others by fully participating with your mind. Feel the air fill your lungs. Feel your muscles work. Feel your body as a whole. Visualize precious life energy entering your lungs and every cell of your body, rejuvenating and energizing you. To help you experience this exercise more profoundly, keep your eyes closed. Place your hands on your abdomen and feel it expand upon inhalation.

Chest-to-belly breathing

Folks in the West sit in chairs and bend forward too much. The daily sitting routine begins in the early morning when they go to the bathroom and then lean over the sink to brush their teeth and then continues throughout the day, usually ending as they sit in front of the television at home until their eyes get blurry. The chest-to-belly breathing emphasizes arching the spine and the upper back to compensate for all this bending forward throughout the day, and it also works well for moving into and out of yoga postures. Chest-to-belly breathing is also an excellent energizer in the morning; you can do it even before you hop out of bed. Don’t do this exercise late at night, though, because it’s likely to keep you awake.

You can practice the following exercise lying down, seated, or even while walking.

-

Lie flat on your back, with your knees bent and your feet on the floor at hip width, and relax.

Place a small pillow or folded blanket under your head if you have tension in your neck or if your chin tilts upward. Place a large pillow under your knees if your back is uncomfortable.

- Inhale while expanding the chest from the top down and continuing this movement downward into the belly; pause for a couple of seconds.

- Exhale while gently contracting and drawing the belly inward, starting just below the navel; pause for a couple of seconds.

- Repeat Steps 2 and 3 from 6 to 12 times.

The Abdominal Breath

Do the Abdominal Breath when you’re feeling tension, stress, or fatigue. This breath relaxes you. A few minutes of deep abdominal breathing can help bring greater connectedness between your mind and your body. The goal is to shift from upper chest, short, shallow breathing to deeper abdominal breathing. Concentrate on your breath and try to breathe in and out gently through your nose. With each breath, allow any tension in your body to slip away. After you start breathing slowly with your abdominals, sit quietly and enjoy the sensation of physical relaxation.

Follow these steps to practice the Abdominal Breath:

- Lie on your back or sit comfortably in a chair.

- Place one hand on your abdomen just above your pubic bone and below your navel; place your other hand on your solar plexus right beneath your breastbone.

-

Listening to your breath, inhale slowly and deeply through your nostrils — so deeply that your belly expands and you feel a wave of breath moving into the bottom, or lowest recesses, of your lungs.

Get down to the bottom of your lungs with this inhalation, going as low and as deep inside your lungs as you can. You can feel the rounding of your abdomen in your hands such that your hands rise a bit and your abdominal cavity pushes upward. Meanwhile, your chest opens and expands gently as if your abdomen is a balloon filling with air evenly and equally in all directions.

-

At the top of your inhalation, find the point of transition where the inhale becomes an exhale.

At the top of every breath is a point of passage, the place where the inhale ends and the exhale begins. Find that place within your lungs and pause a moment to notice how your breath gently begins to shift in a new direction.

-

To a count of six to eight (or more) seconds, exhale fully through your nostrils.

Feel your whole body releasing tension and letting go. Allow your body, including your arms and legs, to relax and go limp.

Do ten slow, full Abdominal Breaths.

The Abdominal Breath is very relaxing. It really works when done well, and for that reason, you may not want to practice it while you’re driving.

The Abdominal Breath is very relaxing. It really works when done well, and for that reason, you may not want to practice it while you’re driving.

The Ocean Breath

The Ocean Breath — sometimes called “rib breathing” or the “upward-moving breath” — oxygenates your blood, stimulates your circulation, and gives you a burst of energy.

You emit a sound during the Ocean Breath — the sound (you guessed it) of an ocean breeze. You stay in your chest and fill your lungs from the diaphragm upward. To stay inflated, your lungs rely on a vacuumlike action inside your chest, and then you push out a full, deep, and complete exhalation through your nostrils. This breath is different from the Complete Breath because you mostly engage your chest and rib cage, and you gently contract your abdomen.

Follow these steps to practice the Ocean Breath:

- Stand or sit comfortably with your spine straight.

- Place your arms on your chest with the fingers of your right hand tucked into your left armpit and the fingers of your left hand tucked into your right armpit.

- Close your eyes or gaze straight ahead with your windpipe open, your jaw and mouth relaxed, and your chin pointing gently downward.

-

Inhale to a count of six to ten, engaging the sipping muscles in the back of your throat as if you’re sipping through a straw, and feel your ribs opening and your breath filling to the top of your lungs.

Inhale to whichever count you can manage best.

Pay attention to the tip of your nose as you inhale. It enhances the sensation of filling your chest all the way up.

Pay attention to the tip of your nose as you inhale. It enhances the sensation of filling your chest all the way up.

-

Gently, but with some commitment and determination, exhale steadily through your nostrils until the exhale is complete.

Feel your breath passing from the back of your throat, across the roof of your mouth, and out your nostrils. You hear a hissing sound, something similar to the sound of a hose when you turn it on and the water begins rushing out.

Never push too hard; this breath is dynamic, but never forced. Feel yourself releasing the air. When you push the air out, your abdominal muscles come into play a bit more. The exhale is something like a volcanic eruption that begins at the diaphragm and rises with increasing strength.

Take 10 Ocean Breaths; pause to rest; do 10 more; pause to rest again; and if you like the results, do 10 more for a total of 30 breaths. Then you can let your abdomen relax and your breath normalize once again.

Perfecting the Ocean Breath takes time, especially when you try smoothing out the transition between inhaling and exhaling, but stick with it. As yoga teacher Sherri Baptiste says, “Breath into breath, moment into moment.”

The Balancing Breath

The object of the Balancing Breath is to develop a conscious control of your breathing. Try this simple breathing technique when you feel tired or overwhelmed or when you just want to clear your head for a moment.

Follow these steps to practice a Balancing Breath:

-

Sit, lie down, or stand with your shoulders, mouth, and jaw relaxed.

Your choice: Gaze softly straight ahead or close your eyes. Make sure your back is erect but not rigid.

-

To a count of four, slowly inhale through your nose.

Feel your breath expanding into your abdomen, mid-body (the diaphragm area), and upper chest. Without forcing, engage and gently fill your lungs to their full capacity.

-

To a count of four, exhale slowly through your nose, drawing your abdomen gently in and up to help send the breath smoothly out.

Although your breath empties from your lungs, focus on releasing it first with your abdomen, and then with your diaphragm, and then with your upper chest. Emit all the air from your lungs.

Practice the Balancing Breath six to ten times — inhaling to a count of four and exhaling to a count of four — pause to rest for a moment, and then do another six to ten Balancing Breaths.

The Cleansing Breath

The purpose of the Cleansing Breath is to clean and clear out your lungs. This breath is unique, because instead of exhaling through your nose, you exhale through your mouth as you purse your lips. Pursing your lips creates pressure on your airways and helps keep them open so stale air can exit your lungs. It feels almost as though you’re releasing pent-up emotions when you do the Cleansing Breath. In effect, you emit a “sigh of relief.”

If you can, practice the Cleansing Breath outside in the fresh morning air. Follow these steps to practice a Cleansing Breath:

-

Inhale a Complete Breath comfortably through your nostrils to the count of four to six.

You can find the Complete Breath in the section “The Complete Breath” earlier in this chapter.

-

Gently purse your lips as you strongly exhale to a count of four.

Exhale vigorously so you make a loud whooshing sound. Feel your breath rising from the bottom to the top of your lungs in a dynamic and complete release. Refreshing, isn’t it? You feel as though you’re cleansing your entire system.

Gently contracting your abdominal muscles as you exhale helps push the air out.

Gently contracting your abdominal muscles as you exhale helps push the air out.

Complete this breath four to six times.

The Vitality Breath

The Vitality Breath sends energy to all parts of your body and makes you feel more alive.

Follow these steps to practice the Vitality Breath:

-

Stand upright with your feet spread wider than your hips and your toes pointing forward.

Make sure your body weight is well-balanced between both legs.

-

While inhaling a Complete Breath through your nostrils to the count of four, extend your arms straight out in front of you, palms facing upward.

This is the starting position.

For an explanation of the Complete Breath, refer to the section “The Complete Breath” earlier in this chapter. Although you hold your arms in front of you, you should hold them in a relaxed manner.

-

Exhale slowly through your mouth or through pursed lips as you draw your hands toward your body along the sides of your rib cage and gradually contract the muscles of your arms and hands.

By the time your arms and hands reach the sides of your body, contract your muscles so that your fists are clenched. Put some force into it. At this point, your fists should be tightly clenched, and you should feel a driving force or sense of inner release as you exhale.

-

Relax your arms and hands as you deeply inhale, slowly unclench your fists, and return to the starting position (see Step 2).

Imagine that you’re taking in this breath through your hands and heart.

Repeat Steps 2 through 4 six to eight times to complete six to eight Vitality Breaths.

Understanding breathing basics

Understanding breathing basics Detailing yogic breathing mechanics and techniques

Detailing yogic breathing mechanics and techniques During your normal breathing, you may notice a slight natural pause between inhalation and exhalation. This pause becomes important in yogic breathing; even though it lasts only one or two seconds, the pause is a natural moment of stillness and meditation. If you pay attention to this pause, it can help you become more aware of the unity among body, breath, and mind — all of which are key elements in your yoga practice. With the help of a teacher, you also can discover how to lengthen the pause during various yoga postures to heighten its positive effects.

During your normal breathing, you may notice a slight natural pause between inhalation and exhalation. This pause becomes important in yogic breathing; even though it lasts only one or two seconds, the pause is a natural moment of stillness and meditation. If you pay attention to this pause, it can help you become more aware of the unity among body, breath, and mind — all of which are key elements in your yoga practice. With the help of a teacher, you also can discover how to lengthen the pause during various yoga postures to heighten its positive effects. Yogic breathing involves breathing much more deeply than usual, which, in turn, brings more oxygen into your system. Don’t be surprised if you feel a little lightheaded or even dizzy in the beginning. If this situation happens during your yoga practice, just rest for a few minutes or lie down until you feel like proceeding. Remind yourself that you don’t need to rush.

Yogic breathing involves breathing much more deeply than usual, which, in turn, brings more oxygen into your system. Don’t be surprised if you feel a little lightheaded or even dizzy in the beginning. If this situation happens during your yoga practice, just rest for a few minutes or lie down until you feel like proceeding. Remind yourself that you don’t need to rush. The Abdominal Breath is very relaxing. It really works when done well, and for that reason, you may not want to practice it while you’re driving.

The Abdominal Breath is very relaxing. It really works when done well, and for that reason, you may not want to practice it while you’re driving.