Born in 1874, the Master had celebrated his sixty-fourth birthday a few days before with a modest private gathering appropriate to a time of national crisis.

“I wonder which of us is older, the Kōyōkan or I,” he remarked before the second session.

He reminisced upon the fact that such Meiji Go players as Murase Shuho of the Eighth Rank and Shuei, Master in the Honnimbō line to which he himself belonged, had played in this Kōyōkan.

The second session was held in an upstairs room which had the mellow look of Meiji about it. The decorations were in keeping with the name Kōyōkan, “House of the Autumn Leaves.” The sliding doors and the openwork panels above were decorated with maple leaves, and the screen off in a corner was bright with maple leaves painted in the Korin fashion. The arrangement in the alcove was of evergreen leaves and dahlias. The doors of this eighteen-mat room had been opened to the fifteen-mat room next door, so that the somewhat exaggerated arrangement did not seem out of place. The dahlias were slightly wilted. No one entered or left the room save a maid with flowered bodkins in a childlike Japanese coiffure who occasionally came to pour tea. The Master’s fan, reflected in a black lacquer tray on which she had brought ice water, was utterly quiet. I was the only reporter present.

Otaké of the Seventh Rank was wearing an unlined black kimono of glossy habutaé silk and a crested gossamer-net cloak. Somewhat less formal today, the Master wore a cloak with embroidered crests. The first day’s board had been replaced.

The two opening plays had been ceremonial, and serious play began today. As he deliberated Black 3, Otaké fanned himself and folded his hands behind him, and put the fan on his knee like an added support for the hand on which he now rested his chin. And as he deliberated—see—the Master’s breathing was quicker, his shoulders were heaving. Yet there was nothing to suggest disorder. The waves that passed through his shoulders were quite regular. They were to me like a concentration of violence, or the doings of some mysterious power that had taken possession of the Master. The effect was the stronger for the fact that the Master himself seemed unaware of what was happening. Immediately the violence passed. The Master was quiet again. His breathing was normal, though one could not have said at what moment the quiet had come. I wondered if this marked the point of departure, the crossing of the line, for the spirit facing battle. I wondered if I was witness to the workings of the Master’s soul as, all unconsciously, it received its inspiration, was host to the afflatus. Or was I watching a passage to enlightenment as the soul threw off all sense of identity and the fires of combat were quenched? Was it what had made “the invincible Master”?

At the beginning of the session Otaké had offered formal greetings, after which he had said: “I hope you won’t mind, sir, if I have to get up from time to time.”

“I have the same trouble myself,” said the Master. “I have to get up two and three times every night.”

It was odd that, despite this apparent understanding, the Master seemed to sense none of the nervous tension in Otaké.

When I am at work myself, I drink tea incessantly and am forever having to leave my desk, and sometimes I have nervous indigestion as well. Otaké’s trouble was more extreme. He was unique among competitors at the grand spring and autumn tournaments. He would drink enormously from the large pot he kept at his side. Wu9 of the Sixth Rank, who was at the time one of his more interesting adversaries, also suffered at the Go board from nervous enuresis. I have seen him get up ten times and more in the course of four or five hours of play. Though he did not have Otaké’s addiction to tea, there would all the same (and one marveled at the fact) come sounds from the urinal each time he left the board. With Otaké the difficulty did not stop at enuresis. One noted with curiosity that he would leave his overskirt behind him in the hallway and his obi as well.

After six minutes of thought he played Black 3; and immediately he said, “Excuse me, please,” and got up. He got up again when he had played Black 5.

The Master had quietly lighted a cigarette from the package in his kimono sleeve.

While deliberating Black 5, Otaké put his hands inside his kimono, and folded his arms, and brought his hands down beside his knees, and brushed an invisible speck of dust from the board, and turned one of the Master’s white stones right side up. If the white stones had face and obverse, then the face must be the inner, stripeless side of the clamshell; but few paid attention to such details. The Master would indifferently play his stones with either side up, and Otaké would now and again turn one over.

“The Master is so quiet,” Otaké once said, half jokingly. “The quiet is always tripping me up. I prefer noise. All this quietness wears me down.”

Otaké was much given to jesting when he was at the board; but since the Master offered no sign that he even noticed, the effect was somewhat blunted. In a match with the Master, Otaké was unwontedly meek.

Perhaps the dignity with which the real professional faces the board comes with middle age, perhaps the young have no use for it. In any case, younger players indulge all manner of odd quirks. To me the strangest was a young player of the Fourth Rank who, at the grand tournament, would open a literary magazine on his knee and read a story while waiting for his adversary to play. When the play had been made, he would look up, deliberate his own play, and, having played, turn nonchalantly to the magazine again. He seemed to be deriding his adversary, and one would not have been surprised had the latter taken umbrage. I heard one day that the young player had shortly afterwards gone insane. Perhaps, given the precarious state of his nerves, he could not tolerate those periods of deliberation.

I have heard that Otaké of the Seventh Rank and Wu of the Sixth once went to a clairvoyant and asked for advice on how to win. The proper method, said the man, was to lose all awareness of self while awaiting an adversary’s play. Some years after this retirement match, and shortly before his own death, Onoda of the Sixth Rank, one of the judges at the retirement match, had a perfect record at the grand tournament and gave evidence of remarkable resources left over. His manner at play was equally remarkable. While awaiting a play he would sit quietly with his eyes closed. He explained that he was ridding himself of the desire to win. Shortly after the tournament he went into a hospital, and he died without knowing that he had had stomach cancer. Kubomatsu of the Sixth Rank, who had been one of Otaké’s boyhood teachers, also put together an unusual string of victories in the last tournament before his death.

Seated at the board, the Master and Otaké presented a complete contrast, quiet against constant motion, nervelessness against nervous tension. Once he had sunk himself into a session, the Master did not leave the board. A player can often read a great deal into his adversary’s manner and expression; but it is said that among professional players the Master alone could read nothing. Yet for all the outward tension, Otaké’s game was far from nervous. It was a powerful, concentrated game. Given to long deliberation, he habitually ran out of time. As the deadline approached he would ask the recorder to read off the seconds, and in the final minute make a hundred plays and a hundred fifty plays, with a surging violence such as to unnerve his opponent.

Otaké’s way of sitting down and getting up again was as if readying himself for battle. It was probably for him what the quickened breathing was for the Master. Yet the heaving of those thin, hunched shoulders was what struck me most forcefully. I felt as if I were the uninvited witness to the secret advent of inspiration, painless, calm, unknown to the Master and not perceived by others.

But afterwards it seemed to me that I had rather outdone myself. Perhaps the Master had but felt a twinge of pain in his chest. His heart condition was worse as the match progressed, and perhaps he had felt the first spasm at that moment. Not knowing of the heart ailment, I had reacted as I had, probably, out of respect for the Master. I should have been more coolly rational. But the Master himself seemed unaware of his illness and of the heavy breathing. No sign of pain or disquiet came over his face, nor did he press a hand to his chest.

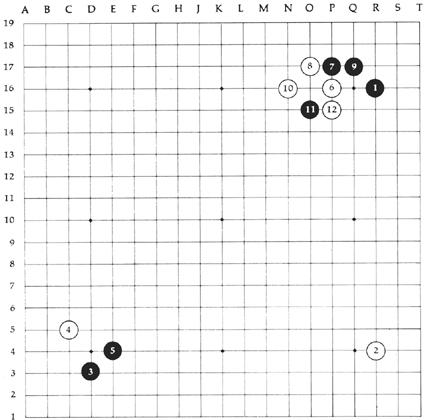

Otaké’s Black 5 took twenty minutes, and the Master used forty-one minutes for White 6, the first considerable period of deliberation in the match. Since it had been arranged that the player whose turn came at four in the afternoon would seal his play, the sealed play would be the Master’s unless he played within two minutes. Otaké’s Black 11 had come at two minutes before the hour. The Master sealed his White 12 at twenty-two minutes after the hour.

The skies, clear in the morning, had clouded over. The storm that was to bring floods in both the east and the west of Japan was on its way.10