The Master was like a starved urchin in his appetite for games. Shut up in his room with his games, he was doing his heart ailment no good. An introspective person, however, not given to easy switches of mood, he probably found that only games quieted his nerves and turned his mind from Go. He never went for walks.

Most professional Go players like other games as well, but the Master’s addiction was rather special. He could not play an easy, nonchalant match, letting well enough alone. There was no end to his patience and endurance. He played day and night, his obsession somewhat disquieting. It was less as if he were playing to dispel gloom or beguile tedium than as if he were giving himself up to the fangs of gaming devils. He gave himself to mahjong and billiards just as he gave himself to Go. If one put aside the inconvenience he caused his adversaries, it might have been said, perhaps, that the Master himself was forever true and clean. Unlike an ordinary person with preoccupations of some intensity, the Master seemed to be lost in vast distances.

Even in the interval between a session and dinner, he would be at one game or another. Iwamoto would not yet have finished his flagon of saké when the Master would come impatiently for him.

At the end of the first Hakoné session, Otaké asked the maid for a Go board as soon as he was back in his room. We could hear stones clicking as, apparently, he reviewed the course of the game. The Master, now in a cotton kimono, promptly appeared at the managers’ office. With great dispatch he defeated me at five and six matches of Ninuki Renju.

“But it’s such a lightweight game,” he said fretfully as he went out. “We’ll play chess. There’s a board in Mr. Uragami’s room.”

His match with Iwamoto at rook’s handicap26 was interrupted by dinner.

Happy from his evening drink, Iwamoto sat grandly with his legs crossed and slapped away at his bare thighs; and in due order he lost.

After dinner a clicking of stones came sporadically from Otaké’s room; but soon he came down for rook-handicap games with Sunada of the Nichinichi and myself.

“When I play chess I have to sing. Excuse me, please. I do like chess. I ask myself and ask myself, and for the life of me I can’t understand why I became a Go player instead of a chess player. I’ve been at chess longer than Go. Must have learned it when I was four, maybe not quite, and a person ought to be stronger at the game he learned first.” He would sing happily away at his own versions, dotted with puns and innuendoes, of children’s songs and popular songs.

“I imagine you’re the strongest chess player in the Association,” said the Master.

“I wonder. You’re rather good yourself, you know, sir. But no one in the Association has made even the First Rank at chess. I imagine I’ll always get first play when I play Renju with you. I don’t even know the standard moves. I just elbow my way ahead. I believe that you are Third Rank, sir?”

“But I doubt if I could beat even a First Rank professional. Professionalism gives a person strength.”

“The Master of Chess, Mr. Kimura—how is he at Go?”

“Possibly First Rank. They say he’s improved lately.”

Otaké hummed happily as he did battle with the Master at a no-handicap game. The Master was seduced into humming with him. Such levity was not usual with the Master. His rook having been promoted,27 he had a slight edge.

In those days the Master’s chess games were cheerful and lively, but as illness overtook him that ghostlike quality became apparent. Even after the August 10 session he had to have games to divert him. To me it was as if he were suffering the torments of hell.

The next session was scheduled for August 14. But the Master was far weaker and in great pain. The managers urged suspending the match. The newspaper had resigned itself to the inevitable. The Master made a single play on August 14 and a recess was called.

Seated at the board, each player first took his bowl of stones from the board and set it at his knee. The bowl seemed too heavy for the Master. The players in turn, following the earlier course of the match, laid the stones out as at the end of the last session. The Master’s stones seemed about to slip through his fingers, but as the ranks took shape he seemed to gain strength, and the click of the stones was sharper.

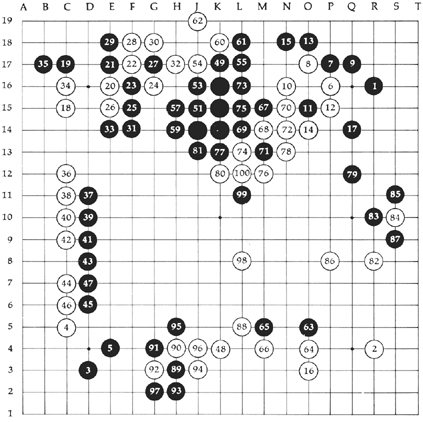

Absolutely motionless, the Master meditated for thirty-three minutes over his one play. It had been agreed that White 100 would be sealed.

The First Hundred Plays

“I can play a little more, I think,” said the Master.

No doubt he was in a mood for battle. The managers held a hasty conference. But a promise was a promise. It was decided to end the session with the one sealed play.

“Very well, then.” Even after he had sealed his White 100, the Master gazed on at the board.

“It has been a long time, sir, and I have caused you a great deal of trouble,” said Otaké. “Do care for yourself.”

“Yes,” was all the Master said. His wife answered at greater length.

“Exactly a hundred plays. How many sessions?” Otaké asked the recorder. “Ten? Two in Tokyo and eight here in Hakoné? Exactly ten plays a session.”

Later when I went to take leave of the Master he was looking vacantly into the sky over the garden.

He was to go immediately into St. Luke’s Hospital, but it seemed unlikely that he could get train accommodations for some days.