“I think I would like if possible to finish today,” the Master said to the managers on the morning of December 4. In the course of the morning’s session he said to Otaké: “Suppose we finish today.” Otaké nodded quietly.

The faithful battle reporter, I felt a tightening in my chest at the thought that after more than half a year the match was to finish today. And the Master’s defeat was clear to everyone.

It was also in the morning, at a time when Otaké was away from the board, that the Master turned to us and smiled pleasantly. “It’s all over. Nothing more to be done.”

I do not know when he had called a barber, but this morning he resembled a shaven-headed priest. He had come to Itō with his hair long and parted, as in the hospital, and dyed black; and now, suddenly, it was cropped short. One might have seen histrionics in this refashioning; yet he seemed young and brisk, as if a layer of aging had been washed away.

December 4 was a Sunday. There were one or two plum blossoms in the garden. Since numbers of guests had come to the inn on Saturday, the session was held in the new addition, in the room that had always been mine, next to the Master’s. The Master’s room was at the far end of the new building. The managers had the night before occupied the two rooms directly above. They were in effect protecting the Master from incursions by other guests. Otaké, who had been on the second floor of the new building, had moved downstairs a day or two before. He was not feeling at all well, he said, and it was a trial to climb up and down stairs.

The new building faced directly south. The garden was wide and open, and direct sunlight fell near the Go board.

His head inclined to one side, his brows wrinkled and his torso sternly upright, the Master gazed at the board while Black 145 was being opened. Otaké played more rapidly, perhaps because he knew he had won.

The tension of the final encounter at close quarters is unlike that through the opening and middle stages. Raw nerves seem to flash, there is something grand and even awesome about the two figures pressing forward into closer combat. Breath came more rapidly, as if two warriors were parrying with dirks; fires of knowledge and wisdom seemed to blaze up.

It was the time when, in an ordinary game, Otaké would be going into his sprint, playing a hundred stones in the course of his last allotted minute. He still had a margin of some six or seven hours, and yet, as if riding the wave of his aroused nerves, he seemed intent upon keeping his momentum. He would reach for a stone as if whipping himself on, and then, from time to time, he would fall into deliberation. Even the Master would sometimes hesitate when he had a stone in his hand.

Watching these last stages was like watching the quick motions of a precisely tooled machine, a relentless mathematical progression, and there was an aesthetic pleasure too in the order and the formal propriety. We were watching a battle, but it took clean forms. The figures of the players themselves, their eyes never leaving the board, added to the formal appropriateness.

From about Black 177 to White 180, Otaké seemed in a state of rapture, in the grip of thoughts too powerful to contain. The round, full face had the completeness and harmony of a Buddha head. It was an indescribably marvelous face—perhaps he had entered a realm of artistic exaltation. He seemed to have forgotten his digestive troubles.

Perhaps too worried to come nearer, Mrs. Otaké, that splendid Momotaro of a baby in her arms, had been walking in the garden, from which she gazed uneasily toward the game room.

The Master, who had just played White 186, looked up as the long siren sounded from the direction of the beach. “There’s room for you all,” he said amiably, turning toward us.

The autumn tournament having ended, Onoda of the Sixth Rank was in attendance. Others too were watching as the battle pressed to a close: Yawata of the Association, Goi and Sunada of the Nichinichi, the Itō correspondent for the Nichinichi, the managers and other functionaries. They were crowded together just inside the anteroom, and some were beyond the partition. The Master was inviting them to watch from nearer the board.

That Buddha countenance lasted for but a moment. Otaké’s face was alive again with a lust for battle. The small, beautifully erect figure of the Master as he counted up points seemed to take on a grandeur that stilled the air around him. When Otaké played Black 191, the Master’s head fell forward, his eyes were wide, he moved nearer the board. Both men were fanning themselves violently. The noon recess came with Black 195.

The afternoon session was moved back to the usual site, Room 6 in the main building. The sky clouded over from shortly after noon, and crows cawed incessantly. There was a light above the board, a sixty-watt bulb. The glare from a hundred watts would have been too much. Faint images the color of the stones fell across the board. Perhaps in special observance of this last session, the innkeeper had changed the hangings in the alcove for twin landscapes by Kawabata Gyokushō.45 Below them was a small statue of a Buddha on an elephant, and beside that a bowl of carrots, cucumbers, tomatoes, mushrooms, trefoil parsley, and the like.

The last stages of a grand match, I had heard, were so horrible that one could scarcely bear to watch. Yet the Master seemed quite unperturbed. One would not have guessed that he was the loser. A flush came over his cheeks from about the two hundredth play, and he seemed a trifle pressed as for the first time he took off his muffler; but his posture remained impeccable. He was utterly quiet when Otaké made the last play, Black 237.

As the Master filled in a neutral point, Onoda said: “It will be five points?”

“Yes, five points,” said the Master. Looking up through swollen eyelids, he made no motion toward rearranging the board. The game had ended at forty-two minutes past two in the afternoon.

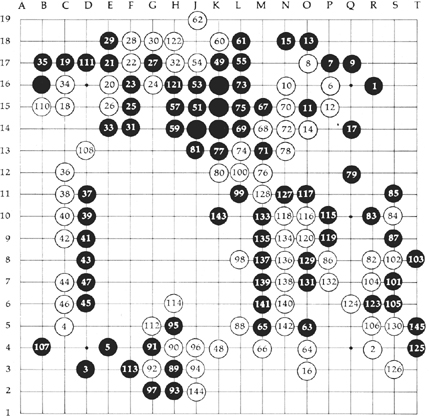

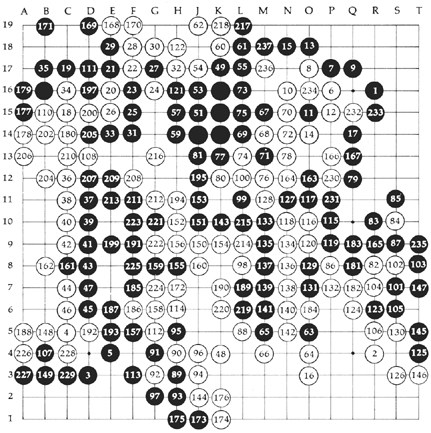

Black 201 and 203 (B-13 and C-13) had been captured with play of White 206, and White 210 placed on C-13, originally occupied by Black 203.

White 196 and 198 (F-10 and E-10) had been captured with play of Black 221, and Black 223 placed on E, originally occupied by White 196.

“I judged before they had redone the board46 that it would be five points,” said the Master, smiling, when the next day he had given his thoughts on the game. “I judged it would be sixty-eight against seventy-three. But I think if you actually redid the board you would not find that many.” He rearranged the board for himself, and came to a score of fifty-six for Black against fifty-one for White.

Until Black succeeded in destroying the White formation after that fatal White 130, no one had predicted a five-point difference. It had been careless of the Master not to take the offensive and cut at R-247 with perhaps White 160, the Master himself said, for he lost a chance thereby to reduce the proportions of Otaké’s victory. One can see that such a play would have narrowed the difference to perhaps three points, even with that unfortunate White 130. What would have been the outcome, then, if the Master had not blundered and the “earthshaking” changes had not come? A defeat for Black? An amateur like myself cannot really say, but I do not think that Black would have lost. I had come almost to believe as an article of faith, from the manner, the resolve, with which Otaké approached the game, that he would avert defeat even if in the process he must chew the stones to bits.

But one may say too that the sixty-four-year-old Master, gravely ill, played well to beat off violent assaults from the foremost representative of the new regulars until the moment late in the game when the initiative quite slipped from his hands. Neither was he taking advantage of poor play by Black nor was he unfolding a grand strategy of his own. The natural flow led into a close and delicate match. Yet perhaps because of his health the Master’s game lacked persistence and tenacity.

“The Invincible Master” had lost his final match.

“The Master seems to have made it a principle to put everything into a game with the next in line, the one who might succeed him,” said a disciple.

Whether or not the Master himself had so stated the principle, he acted upon it throughout his career.

The next day I went home to Kamakura. Then, scarcely able to finish my sixty-six newspaper installments, I went as if fleeing the battlefield on a trip to Isé and Kyoto.

I have heard that the Master stayed on at Itō, and gained weight, some four pounds, until he weighed upwards of seventy pounds; and that he visited a military convalescent home with twenty sets of Go stones. By the end of 1938, hot-spring inns were being used as convalescent homes.