Clay

STEVE SCHAPIRO/CORBIS

The young professional boxer at his mother’s house in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1963.

OUTSIZE TERMS ARE OFTEN APPLIED TO those who have lived outsize lives—terms such as mythic . . . or titanic . . . or transcendent.

Usually, upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that the actual life falls short of the modifier. Not so in the case of Muhammad Ali, a legend in his own or any other time. The high drama he enacted in the arena was more than matched by the drama he generated outside of it. A national hero as a broad-smiling Olympic champ, he came to be detested by many of his countrymen for his religious and political beliefs, then rose again as an idol not just in America but throughout the world. Indeed, it was said that he was, as the 20th century ended, perhaps the best known and most beloved figure in the world. Yes, it was an altogether extraordinary journey—from his birth as Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., on January 17, 1942, in Louisville, Kentucky, to his death, in Phoenix, Arizona, from complications of Parkinson’s disease, on June 3, 2016.

As millions mourned his passing, they returned to the story of his life and found themselves thrilled anew. He came from modest circumstances: His father, Cassius Marcellus Clay Sr., earned a living painting signs and the occasional mural, while his mother, Odessa Grady Clay, at times worked as a housekeeper. Cassius’s youth in segregated Louisville was far from easy, though his lot was better than that of many other black children in town. Although his family didn’t have much money, Cassius and his younger brother had food to eat, Sunday-best clothes (they were raised as Baptists, in their mother’s tradition) and a home that was lit with affection, though not without its problems. Years later, the parents’ marriage would be strained to the point of separation by Clay Sr.’s woman-chasing, along with drinking and occasional violence, but when Cassius was a child, the tensions were light.

He was, as you might imagine, an exuberant boy: talkative, restless, a clown. He’d have his brother throw rocks at him just so he could dodge them. “By the time he was four, he had all the confidence in the world,” Odessa Clay told Thomas Hauser for his 1991 biography, Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times. “Everything he did seemed different as a child. He even had measles and chicken pox at the same time. His mind was like the March wind, blowing every which way. And whenever I thought I could predict what he’d do, he turned around and proved me wrong.”

Cassius found his way to boxing through an incident involving a bicycle—a brand-new red-and-white Schwinn with a headlight and whitewall tires. He was twelve years old on the day that he and a friend left their bikes outside and went into the Louisville Home Show, a local black bazaar held in the Columbia Auditorium, to escape a downpour and take advantage of the free hot dogs and popcorn. When they exited the bazaar, they found that Cassius’s bike had disappeared. During a frantic search for it, the boy was told that there was a police officer in the boxing gym in the auditorium’s basement. Tearful, he went to report the theft. It was clear to the officer, Joe Martin, that the boy was looking to get even, and he made the suggestion that, first, it would be good to learn to fight.

The policeman ran not only the gym but also a local boxing TV show called Tomorrow’s Champions. He taught the boy some beginner’s moves, and six weeks after joining the gym, the 89-pound Cassius Clay went on the show and swung clumsily to Victory No. 1—a split decision in a three-round bout. He took home four dollars.

He announced, not for the last time, that he was destined to become the heavyweight champion of the world.

THE ADOLESCENT CLAY EARNED A REPUTATION FOR single-minded intensity and a dogged devotion to training. He worked six days a week, building on raw talents: sharp reflexes and exceptional foot and hand speed. He learned to use the ring to stymie and wear down opponents. His style was unconventional and deceptively weak-looking, as he relied on his legs and kept his hands low and his head seemingly exposed to punches. When those punches were thrown at him, he would reel straight back to narrowly avoid the blow and then spring forward with a punch of his own.

By the age of eighteen, he had built an impressive amateur record: 100 wins, eight losses, six state and two national Golden Gloves championships and two national Amateur Athletic Union titles. He graduated from high school—barely—in 1960 and set out that summer for the Rome Olympics. Terrified of flying, Clay bought himself a parachute to wear on the airplane. The flight went smoothly enough, and so did the fights: four of them, en route to the gold medal. In a harbinger of the ever-entertaining relationship he would long enjoy with the world’s press, Clay, when asked by a reporter from the Soviet Union how he felt about winning gold for a country in which blacks were barred from eating in many restaurants, responded: “Tell your readers we got qualified people working on that problem, and I’m not worried about the outcome. To me, the U.S.A. is the best country in the world, including yours.” A poem that the eighteen-year-old wrote on the return trip home, which would be published in a black paper in Louisville, amplified those sentiments:

To make America the greatest is my goal,

So I beat the Russian, and I beat the Pole,

And for the USA won the Medal of Gold.

Italians said, “You’re greater than the Cassius of Old.”

We like your name, we like your game,

So make Rome your home if you will.

I said I appreciate your kind hospitality,

But the USA is my country still,

’Cause they waiting to welcome me in Louisville.

Welcome him they did, in high style, with a police escort downtown, cheering crowds, photo ops, a plethora of WELCOME HOME signs. The hoopla greatly pleased Clay, who showed off his medal with pride. He kept it with him at all times, wearing it around his neck at meals and even to sleep. But something was about to happen that would complicate Cassius Clay’s notions of American exceptionalism, and that would come to involve the medal as an enormous symbol.

Even as he was still being celebrated by greater Louisville, Clay and a friend were denied service in one of the city’s restaurants. “We don’t serve Negroes,” a waitress told them, as he recalled in a 2004 autobiography, The Soul of a Butterfly: Reflections on Life’s Journey.

“Well, we don’t eat them either,” Clay joked, before setting the waitress straight about whom, exactly, she was refusing to serve. Her refusal stood.

Clay and his friend left the restaurant, and what happened next has always been hard to pin down. In The Greatest: My Own Story, a somewhat fictionalized memoir written in 1975, Ali claimed that a racist white motorcycle gang followed the two from the restaurant and tangled with them briefly on a bridge over the Ohio River. The boxer then walked to the side of the bridge and, in anger and disgust at everything that had transpired, tossed his gold medal into the flowing waters below.

He told the story various ways through the years, maintaining sometimes that the medal was simply lost. Then, late in life, he returned to a dramatic rendition, writing in The Soul of a Butterfly: “Over the years I have told some people I had lost it, but no one ever found it. That’s because I lost it on purpose. The world should know the truth—it’s somewhere at the bottom of the Ohio River.”

He elaborated: “From that moment on, I have never placed great value on material things . . . If I had kept that medal I would have lost my pride.”

Regardless of the medal’s true fate, the day-to-day racism suffered by Clay was real and it was corrosive, greatly tarnishing the luster of pride he had been feeling. Clay had been deeply affected, and his feelings for his hometown and his country had been roiled.

THE NAME IS TUNNEY HUNSAKER AND YOU CAN LOOK it up. That was the name of Cassius Clay’s first victim as a professional—Tunney Hunsaker, police chief of Fayetteville, West Virginia, loser of a unanimous six-round decision to Clay on October 29, 1960. Hunsaker was the first, Herb Siler the second, Tony Esperti the third, Jimmy Robinson the fourth, Donnie Fleeman the fifth, LaMar Clark the sixth, Duke Sabedong the seventh . . .

Clay was building a reputation as a solid pro fighter, a reputation that was overshadowed, it must be said, by his growing renown as a fast-talking self-promoter: the Louisville Lip. “I’m not the greatest, I’m the double greatest,” he said in 1962. “Not only do I knock ’em out, I pick the round. I’m the boldest, the prettiest, the most superior, most scientific, most skillfullest fighter in the ring today.” Before taking on Henry Cooper in London in 1963, he told the world, “I’m not training too hard for this bum. Henry Cooper is nothing to me. If this bum go over five rounds, I won’t return to the United States for 30 days, that’s final.” He TKO’d Cooper in the fifth.

It was, of course, well-played shtick—ring theater that had been inspired by the antics of the over-the-top professional wrestler Gorgeous George. In point of fact, Clay’s antics cloaked what was a relatively quiet, amiable and youthfully innocent nature. If Clay was cocksure, he was also undeniably sweet.

As he climbed the heavyweight ladder, he now had the fearsome Sonny Liston in his sights. With the win over Cooper, he would get his shot.

Many fight-game observers considered it thoroughly unwise to taunt the fierce Liston in any way, shape or form, but Clay was Clay. “He’s too ugly to be a world’s champ,” he declared. “The world’s champ should be pretty like me.” Also: “I’m going to put that ugly bear on the floor, and after the fight I’m gonna build myself a pretty home and use him as a bearskin rug. Liston even smells like a bear. I’m gonna give him to the local zoo after I whup him.”

He predicted the fight would end in the eighth round and composed a poetic narrative for any who might not be able to catch it. It ended thusly:

Now Clay swings with a right

What a beautiful swing

And the punch raises the bear

Clear out of the ring

Liston is still rising

And the ref wears a frown

For he can’t start counting

Till Sonny comes down

Now Liston disappears from view

The crowd is getting frantic

But our radar stations have picked him up

He’s somewhere over the Atlantic

Who would have thought

When they came to the fight

That they’d witness the launching

Of a human satellite

Yes, the crowd did not dream

When they lay down their money

That they would see

A total eclipse of the Sonny.

I am the greatest!

And yet, Clay was scared. He admitted years later to biographer Thomas Hauser that after all he had done to get Liston’s blood boiling, he feared a pummeling: “He was fixing to kill me.”

But Liston didn’t—couldn’t—deliver the beating. The early rounds of the fight saw Clay not only alive and dancing but actually wearing down the champion. Then, suddenly, in the fourth round, Clay’s eyes began to burn. Although some believed it was accidental contact with a substance that had been used to treat a cut under Liston’s eye, David Remnick, in his 1998 biography, King of the World, writes that a close friend of Liston and of Liston’s lead cornerman Joe Pollino (both of whom are now dead) told Remnick that the fighter ordered Pollino to “juice” his gloves with a substance that would impair Clay.

At the end of the fourth, Clay retreated to his corner and asked trainer Angelo Dundee to end the fight. Dundee washed out his fighter’s eyes instead and pushed him back into the ring, offering one word of advice: “Run!”

That’s what Clay did in the fifth, attempting to keep Liston at bay until his eyes cleared. When they did, Clay roared back in the sixth round, and in a stunning conclusion, Liston didn’t leave his corner at the start of the seventh.

Out on the canvas with his feet shuffling and arms outstretched above his head, Clay exploded in victory.

BILL STRODE/COURIER-JOURNAL

Louisville Central High School student Cassius Clay, 17.

AP

CLAY’S FAMOUS APPRECIATION OF HIS OWN GOOD looks was instilled very early on. In his book The Soul of a Butterfly: Reflections on Life’s Journey, Ali recalled that his mother used to tell him that he had been such a pretty baby, people thought he was a girl. Above is a portrait of the boxer as a young man, in 1954, during preparations for his initial amateur bout against a fellow novice, Ronnie O’Keefe—the very first of so many victims.

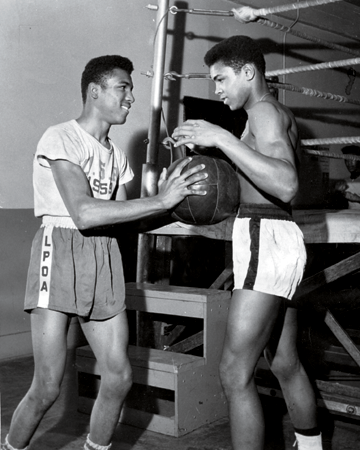

TOM EASTERLING/COURIER-JOURNAL

Brother Rudy helps Cassius harden his stomach muscles with a medicine ball.

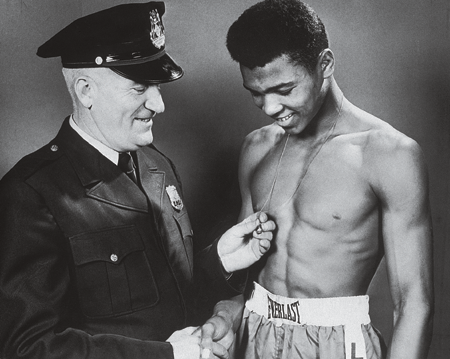

AL BLUNK /COURIER-JOURNAL

THESES PHOTOS WERE TAKEN IN 1959, A YEAR WHEN Cassius’s career took large strides. In the group shot, he is in the top row, with a trophy won on February 18 in Louisville. The following month he would travel to Chicago to take the national Golden Gloves title in his weight class, then in April he would become the National AAU light heavyweight champion. The policeman admiring Clay’s diamond-studded Golden Gloves pendant is Joe Martin, the young boxer’s coach throughout the 1950s. Martin once said of the teenage Clay, “He stood out because he had more determination than most boys. He was a kid willing to make the sacrifices necessary to achieve something worthwhile in sports. It was almost impossible to discourage him. He was easily the hardest worker of any kid I ever taught.”

CHAS. KAYS/COURIER-JOURNAL

BETTMANN/CORBIS

HAVING ARRIVED IN ROME, CLAY IS A happy 18-year-old light heavyweight on the 1960 U.S. Olympic boxing team. If his smile seems appreciably broader than those of his teammates, it’s because he is relieved to have survived the Atlantic crossing. “It was a pretty rough flight,” Joe Martin’s son later told the Louisville Courier-Journal. “He was down in the aisle, praying with his parachute on.”

POPPERFOTO/GETTY

THE COLD WAR WAS AT its most frigid when Clay defeated the U.S.S.R.’s Gennady Schatkov en route to the Olympic finals. There, he beat Zbigniew Pietrzykowski of Poland to win the gold.

HULTON/GETTY

During the medal ceremony, are Clay with Pietrzykowski on his left and joint bronze medalists Giulio Saraudi of Italy and Anthony Madigan of Australia on his right.

AP

On Rome’s Via Veneto, the locals are attracted to Clay’s charisma and his spoils. So gregarious was he, he was anointed the Mayor of Olympic Village—an early, but not his “Greatest,” sobriquet.

BETTMANN/CORBIS

CLAY AND THAT MEDAL WERE INSEPARABLE—UNTIL they weren’t. Any tourist would be a fool not to come home with a nice pair of Italian shoes.

COURIER-JOURNAL

The conquering hero returns gloriously to Central High, which he barely graduated from earlier in the year. As we have learned previously in these pages, whether or not subsequent events in Louisville caused him to toss his medal into the Ohio River shortly after this photograph was taken will, in all probability, never be known for certain.

JEAN A. BARON/COURIER-JOURNAL

HAVING RECEIVED A $10,000 signing bonus from the Louisville Sponsoring Group after turning pro in October 1960, Clay enjoys an Elvis moment and buys his parents a pink Cadillac. There is testimony that at least once that month he would borrow the car. “He was sure a brassy young boy when I fought him,” remembered Tunney Hunsaker, who on October 29 would become Clay’s first professional victim. “He drove to the Louisville Fairgrounds in a brand-new pink Cadillac.”

STEVE SCHAPIRO/CORBIS

FAMILY MATTERS: IN LOUISVILLE IN 1963, CASSIUS is at his mother’s home, all smiles, having already won the Olympic gold medal and amassed a professional record of 18 wins, 15 of them by knockout; mom Odessa can be seen in the background.

STEVE SCHAPIRO/CORBIS

Outside the family house, the well-dressed champ takes a spin with his young fans.

STEVE SCHAPIRO/CORBIS

That same year, Odessa keeps the fuel coming, and the strapping Clay brothers tower over their paternal great-grandmother, Patsy Greathouse, as they escort her to her 99th birthday celebration (below). Odessa raised her two children as Baptists, but both would convert to Islam, and Rudolph Valentino Clay would become Rahaman Ali. He, too, was a boxer, turning professional the night after his brother claimed the heavyweight title in 1964. His career record as a pro was 14 wins (seven by knockout), three losses and a draw.

CHARLES FENTRESS/COURIER-JOURNAL

STEVE SCHAPIRO/CORBIS

The above photo is also a “family matter,” though it seems to involve nothing more than some neighborhood kids hobnobbing with the local celebrity in 1963. The 5-year-old girl in the picture is Lonnie Williams, whose family lived across the street from the Clays. As we will learn in more detail in our book’s final chapter, many years later, in 1986, Lonnie would become Muhammad Ali’s fourth and final wife.

UPI/CORBIS

POLICE CHIEF TUNNEY HUNSAKER DUCKS Clay’s strong left hand during their six-round bout in Louisville, a fight won by Clay in a unanimous decision.

FLIP SCHULKE/BLACK STAR

Clay in 1961 with Angelo Dundee, who became his cornerman that year and stayed with him for life. Their teaming was very much initiated by the boxer and is pure Cassius Clay. He heard that Dundee, already a successful trainer and manager, was in Louisville with one of his boxers, Willie Pastrano. Clay made up his mind and took his shot, as Dundee later recalled: “We were in the hotel room when the phone rang. It was this kid—‘Mr. Dundee, my name is Cassius Clay.’ He gave me a long list of championships he was planning to win and wanted to come up to meet us. I put my hand over the mouthpiece and said to Willie, ‘There’s a nut on the phone; he wants to meet you!’” Clay did meet Pastrano, then joined him in Dundee’s stable; the two fighters were occasional sparring partners in the early 1960s and Pastrano actually became a world champion before Clay did—in the light heavyweight class in 1963. Dundee, for his part, worked with no fewer than 15 champions at various times, including Sugar Ray Leonard, George Foreman and Jimmy Ellis, as well as Clay and Pastrano. He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1994 and died in 2012.

FLIP SCHULKE/BLACK STAR

THREE MONTHS AFTER WINNING AT THE OLYMPICS, Clay, now a professional, moved to Miami to train with Dundee. In that city was a young photographer named Flip Schulke whose work was getting noticed, not least by the editors of LIFE. Schulke knew a good subject when he saw it, and he immediately identified one in Clay. “I fell in love with the guy,” remembered Schulke, who would shoot the boxer over three extended sessions between 1961 and 1964. Schulke’s most famous photos of Clay are the underwater shots taken for LIFE in the pool of the Sir John Hotel in the summer of 1961 (above and below). They are the product of a ruse: Clay told Schulke that he trained underwater—a fib—because he thought shots like the two shown here would look very cool, which of course they do. Less amusing stories that Schulke told later had to do with the racism the photographer saw Clay encounter in Miami; on one occasion, Schulke recalled, the famous fighter was not allowed to try on a shirt in a department store because he was black. It’s unsurprising in retrospect that Schulke was sensitive to such slights: He went on to renown as one of the great photographers of the civil rights movement. For his body of work on that subject he was awarded the Crystal Eagle Award by the National Press Photographers Association.

FLIP SCHULKE/BLACK STAR

HAROLD P. MATOSIAN/AP

The most brazen manifestation of Clay’s cheerful bravado was his predilection for prediction. On the chalkboard he presages that the great but aging Archie Moore will fall in four in 1962. In fact, Clay did stop Moore with a technical knockout in the fourth round of their bout in L.A.

MARVIN LICHTNER/PIX INC./THE LIFE IMAGES COLLECTION/GETTY

The three fingers indicate that Powell will go down in three in ’63, and again Clay made good on his promise with a third-round knockout.

MARVIN LICHTNER/PIX INC./THE LIFE IMAGES COLLECTION/GETTY

YEARS BEFORE THE ATLANTA MEDIA MOGUL and braggadocio yachtsman Ted Turner was dubbed the Mouth of the South, Clay could have claimed that title. But his given nickname, the Louisville Lip, served just as well. When expounding on any aspect of boxing, or indeed any aspect of life itself, as depicted in this picture (above) of the bare-chested boxer taken in a Pittsburgh hotel room before his fight with Charley Powell in 1963, the fighter’s jaws got a workout as intense as anything Dundee could throw at him in the ring.

MARVIN LICHTNER/PIX INC./THE LIFE IMAGES COLLECTION/GETTY

CLAY’S OUTER BRASHNESS AND SELF- celebrated vanity were entertaining because, somehow, the young man’s inner sweetness always shone through; he was clearly in on the joke (until the joking turned overly mean-spirited in his rivalry with Joe Frazier). Here, Clay primps in his hotel room before heading out to fight Powell. The jazz albums by organist Jimmy Smith and saxophonist John Coltrane reflect Clay’s musical tastes at the time.

JAMES DRAKE/THE LIFE IMAGES COLLECTION/GETTY

THREE PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE early months of 1963 well illustrate the duality of Clay’s approach to the fight game. He loved to spar with the press both before and after fights, which led Angelo Dundee to tape his fighter’s mouth shut at the weigh-in for a March 13 bout in New York City against Doug Jones (which Clay would win by unanimous decision after 10 rounds).

GEORGE SILK/LIFE/THE PICTURE COLLECTION

MARVIN LICHTNER/PIX INC./THE LIFE IMAGES COLLECTION/GETTY

But such antics are altogether absent in the photograph above, taken in a Pittsburgh locker room as Clay gets his hands taped for his fight with Powell. As his first trainer, Joe Martin, observed: No one was more dedicated to craft than Clay, and it was a grave mistake for any opponent to consider the man more an entertainer than an athlete. This was not yet a widely held view in 1963; the showboating certainly contributed to Clay’s being considered a huge underdog when he would finally get his shot at the crown. But from the vantage point of years, it is evident that Clay, far more than just a clown, was an Einstein of the sweet science, an absolute master of the brutal art of boxing.

EXPRESS/HULTON/GETTY

STRIDING THE STREETS OF NEW YORK CITY IN THE SPRING of 1963 , Clay, who is ostentatiously and very purposely dressed in Savile Row–style finery, signals that his next bout is to take place in Merrie Olde England—in London, to be precise, on June 18 against the formidable Brit Henry Cooper. Clay will win the fight (although he will be knocked down by the heavy-punching Cooper), and the fifth-round TKO will earn him a shot at the heavyweight crown.

JAMES DRAKE/THE LIFE IMAGES COLLECTION/GETTY

These nuns in the library of Louisville’s Nazareth College (today, Spalding University), where Clay had once briefly earned extra money by sweeping the floor, are charmed by the local legend’s visit, also in ’63. If the good sisters are knowledgeable about boxing in the least, they surely pray long and hard for Clay, since the man he hopes to dethrone next year is the fearsome Charles L. “Sonny” Liston, a.k.a. the Big Bear, an ex-con with ties to organized crime and a constant scowl. In Liston’s previous two fights, he had taken the heavyweight title from the talented Floyd Patterson with a first-round knockout, then successfully defended the crown with another knockout of Patterson—this one taking two seconds longer to accomplish. The odds against Clay beating Liston are established at seven to one.

PHOTOGRAPH © HARRY BENSON 1964

WHEN IT COMES TO WEIGHT OF fame per frame, pound for pound, this photograph, from mid- February 1964, is hard to top: five of the most famous pop-culture figures of the 20th century hamming it up. The Beatles are in Miami Beach at the absolute height of their global celebrity when they visit Clay, who is training in the neighborhood a week before the Liston fight. Well, they don’t exactly “visit” Clay; they are brought to him by Harry Benson, the photographer who will make this famous picture. John Lennon (second from left) had agreed to an audience with Liston and was firmly opposed to the band’s posing with Clay, “that big mouth who’s going to lose.” But Liston refused to meet with those “bums,” and so Benson twisted some arms and set up what, historically speaking, would prove to be a much more important summit. Once at Clay’s camp, the Beatles nearly walk out. Then the fighter emerges from his dressing room bellowing, “Hello there, Beatles. We oughta do some road shows together. We’ll get rich.” The Fab Five then proceed to horse around for Benson’s camera for several minutes, with the musicians falling en masse to a mighty blow from the boxer. “Degrading,” one of the Beatles says to Benson afterward. “You made a fool of us.” Lennon won’t speak to Benson for two weeks. A postscript: Benson, a Scotsman who was at the time working as a Fleet Street photographer, had earlier made the equally famous pillow-fight photo of the Beatles.

CORBIS

DESPITE THE COCKINESS EXPRESSED IN HIS poems and predictions—“The man needs boxing lessons,” he said in the run-up to the Liston bout—Clay, who was, as we have said, a most serious sportsman, was not one to underestimate an opponent. He went into training for the title fight with characteristic earnestness and intensity. In hindsight, it can be considered an advantage for the challenger that the event was booked for the Miami Convention Center, which meant home cooking at the Dundee encampment (where Clay monitors his moves in a mirror five days before the February 25, 1964, bout). After a workout, Clay would leave the enclave and drive a busload of his supporters over to the Liston training camp, where he would taunt “the big, ugly bear.” This time, he predicted an eighth-round knockout—but few, if any, were buying. Noted sportswriter Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times wrote, “The only thing at which Clay can beat Liston is reading the dictionary.” The New York Times’s boxing writer, Joe Nichols, didn’t even travel down to Miami to cover the match, assuming it would be brief and predictable, ending with Clay on the canvas.

MARVIN LICHTNER/PIX INC./THE LIFE IMAGES COLLECTION/GETTY

HERB SCHARFMAN/SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

REALIZING THAT LISTON will not answer the bell for the seventh round, Clay exults and flies into his “I shook up the world!” dance. Cornermen Drew “Bundini” Brown (hugging the champ) and Angelo Dundee join the celebration. But not all in the Clay camp had been optimistic: His own sponsors had failed to plan a victory celebration, and by the time they cobble together some arrangements after the fight, Clay is in Malcolm X’s hotel room, happily eating ice cream and partying with the Black Muslim leader, football legend Jim Brown and others. With this scene, the first chapter of Clay’s life draws to a close, although no one could have predicted at the time how emphatically this would be so. He is only 22 and is now the champion of the world. But he is also on the verge of cutting ties with much that had come before—with, in fact, himself. He will say goodbye to Cassius Clay and begin life as Muhammad Ali. That will change almost everything. Almost. There will be one crucial constant: boxing. The man will continue to box, as marvelously as anyone ever has.