Ali

BETTMANN/CORBIS

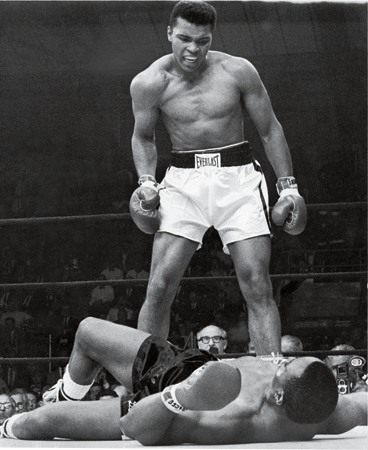

Muhammad Ali stands over Sonny Liston in round one of their rematch and dares him to “Get up and fight.” Liston will not.

HE WAS STILL, TO THE WIDER WORLD, Cassius Clay, the brash young boxing champion from Louisville. He was the kid who had won the gold in Rome and stunned the sports world by dethroning Sonny Liston. He was the comedian, the happy-go-lucky prodder of dangerous men, the preening poet laureate of the ring.

But to himself and some of his closest confidants, he was already someone other. Who this new man was—what he believed, what philosophies and causes he would commit to—would have consequences for the athlete, his sport and, it can be said, society at large. The Cassius Clay story was about to take an enormous and unexpected turn. Another way to look at it: The Cassius Clay story was about to come to its end.

Beneath the public radar, Clay had been pursuing for a few years in the early 1960s a budding interest in Islam, as taught by the Nation of Islam, which at the time was a highly controversial offshoot of orthodox Islam that mixed theology with black nationalism. The Nation’s message of racial pride, self- respect and separation from white “devils” put it at odds with other, more moderate civil rights organizations, and many whites felt threatened by it. At the time, Malcolm X was the movement’s most prominent minister, and until Malcolm’s schism with the Nation’s leadership in March 1964, he and Clay were close friends.

In those first months of ’64, Malcolm X and Clay were both in the national spotlight, though for very different reasons: Malcolm because he had said that the recent assassination of John F. Kennedy represented “chickens coming home to roost,” causing widespread outrage, and Clay because his February 25 title bout with Liston was looming. In fact, skittishness over Clay’s association with Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam threatened to scuttle the fight, so the Clay camp was counseled to downplay the connection.

But the day after becoming world champ, Clay calmly affirmed his beliefs publicly. “I know where I’m going and I know the truth, and I don’t have to be what you want me to be,” he said. “I’m free to be what I want.” Just over a week later, the leader of the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, offered Clay the opportunity to shed his so-called slave name—a name that, ironically, came from the (unrelated) 19th-century abolitionist and politician Cassius Clay—and to take a new one: Muhammad Ali.

The boxer’s defiant enlistment in the Nation’s ranks stunned not only the boxing world and many journalists who covered it but the general public as well. In that tumultuous period of American race relations, Ali’s move challenged long-standing expectations of docility that many whites North and South held for blacks in general and for black athletes and entertainers in particular. It would be years before the fighter’s new name would be widely recognized by the press. (A note in passing: In researching photography for this book in the LIFE archives, the editors found much of it labeled CLAY well into the 1970s.)

As the world heavyweight champion, Muhammad Ali was already a potent symbol of power, and now people also began to see in him a symbol—loved and loathed—of pride, rebellion and generational shift. Something else was happening as well: Ali was transcending the arena. He was not merely a “sports star” anymore, he was a world citizen of consequence who mattered in myriad ways. “People are always telling me what a good example I could set for my people if I just wasn’t a Muslim,” Ali said. “I’ve heard over and over, how come I couldn’t be like Joe Louis and Sugar Ray. Well, they’re gone now, and the black man’s condition is just the same, ain’t it? We’re still catching hell.”

After Ali’s conversion, members of the Nation of Islam became an increasingly prominent and influential presence in the fighter’s camp. Elijah Muhammad’s son Herbert would become Ali’s manager in 1966—a role he would maintain for the rest of the boxer’s career—but even before that, he played the part of matchmaker. In July of 1964, Herbert introduced Ali to twenty-three-year-old cocktail waitress Sonji Roi, and as she later told biographer Thomas Hauser, Ali proposed that very night. They married a little more than a month later. Interestingly, considering that Herbert was the original go-between, Roi’s objections to Islamic rules regarding women’s dress contributed to the marriage’s dissolution in 1966. She told Hauser: “The best times we had together were when everybody else was gone and he could be himself, and it wasn’t necessary for him to be the Muslim.”

ALI CHANGED HIS LIFE IN EARLY 1964 BUT NOT HIS career. As soon as Liston refused to answer the bell for the seventh round on February 25, there was clamor for a rematch. This was finally set for May 25, 1965, in Lewiston, Maine, and despite the outcome of the first fight, there were high expectations in many corners—and, thanks to the Nation of Islam contretemps, high hopes—that Liston would gain his revenge. But Ali made remarkably quick work of the big man with a fast right to the head and a first-round knockout.

Controversy stained the outcome: Was Liston felled by a “phantom punch”? Was the fight fixed? The turmoil seemed reflective of everything that was going on at the time in American society and, particularly, in Ali’s world. Malcolm X had been assassinated a few months earlier; Ali’s marriage to Sonji was already deteriorating. And then, in February 1966, Ali became eligible for the military draft. He had previously been disqualified for service on the basis of an IQ test, but with the rapid escalation of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, eligibility requirements were being relaxed.

Reporters demanded to know what Ali thought about the war and whether he would comply with the selective service. Flustered amid a hailstorm of questions, Ali blurted, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.” He also questioned the notion of fighting for the rights of people elsewhere while black Americans were being marginalized at home.

Ali first bid unsuccessfully to gain status as a conscientious objector on the basis of his religion, which he said prevented him from fighting in non-Muslim wars. Then, on April 28, 1967, at an induction proceeding, he simply refused to enter the military, stating that doing so would be a betrayal of Islam. Furthermore, he issued a statement saying he disagreed with the idea that he had but two choices: the Army or prison. “There is another alternative,” he wrote, “and that alternative is justice.”

IN THE YEAR SINCE HE HAD BEGUN FIGHTING THE DRAFT, Ali had continued to fight in the ring, masterfully turning back challengers including Henry Cooper (once again), Karl Mildenberger, Cleveland Williams, Ernie Terrell and Zora Folley. But now, with Ali’s formal defiance of the government, boxing authorities across the land moved swiftly to ban him from the fight game. They stripped him of his heavyweight title. Ali’s reaction was as indignant as it was insightful: “Everybody knows I’m the champion. My ghost will haunt all the arenas.”

The next to move against Ali was the judicial system. At his trial in June 1967, he was found guilty of refusing to enter the military. His passport was taken away (shutting down any hope of sustaining himself by boxing abroad) and he received the maximum sentence of five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. During the next four years, Ali would stay at liberty as he appealed the decision all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

He was twenty-five years old, undefeated in 29 professional bouts, and Ali could do nothing but watch his prime fighting years slip away and wonder what incarceration would be like, should his court appeals fail.

There was, however, some light in his world. Ali had grown close to seventeen-year-old Belinda Boyd, an observant Muslim within the Nation of Islam community, and they were married in Chicago two months after his trial. They would have four children and, until Ali’s return to the ring, would make ends meet outside of the boxing world. At one point Ali starred in a Broadway musical, but he found more regular work on the college lecture circuit. Even while his legacy as an athlete was in limbo, his reputation as a man of conviction—a person of substance—was growing.

Ali’s fate, as it turned out, was inextricably tied to the Vietnam War. Sentiment in the United States was increasingly turning against the conflict, and sympathy for Ali, and for what many were coming to regard as his principled stance, was growing. Biographer Hauser put it well: “It had become clear to all that, if nothing else, Ali was sincere. At a time when America was being torn apart, when the government was lying to its people, he was speaking the truth as he saw it, if not as it really was.”

Atlanta was the first city to say he could box there again if he wanted to, and on October 26, 1970, he did—triumphantly returning to the ring and beating Jerry Quarry with a third-round technical knockout. He TKO’d Oscar Bonavena in New York City nearly two months later, winning what was then one of three “official” heavyweight titles. The drumbeat grew loud for him to be matched with the holder of the other two, Joe Frazier.

And so, the Fight of the Century—the first time ever that two undefeated heavyweight champions would meet—was set for March 8, 1971, in Gotham’s Madison Square Garden.

Thus was one of the most ferocious, riveting rivalries in sports history joined.

ALI HAD WON HIS FIRST TWO COMEBACK BOUTS, BUT it was clear that time off had taken a physical toll. Notably, his once-confounding speed had dimmed. As a result, he was getting punched like never before. Yes, he was demonstrating, for better or worse, a surprising ability to absorb blows, but nevertheless—he was a different boxer.

His mouth, it’s worth noting, was still in fine shape. “Fifteen referees,” he said during the run-up to the bout. “I want fifteen referees to be at this fight because there ain’t no one man who can keep up with the pace I’m gonna set except me. There’s not a man alive who can whup me. I’m too fast. I’m too smart. I’m too pretty. I should be a postage stamp. That’s the only way I’ll ever get licked.” Ali’s taunting was pitched at a new level as it tapped into the racial turbulence and social upheaval of the times. He painted Frazier as dumb, an Uncle Tom, a boxer that only whites would be rooting for. The words cut Frazier deeply, and the wounds would fester for decades and perhaps never completely heal.

Frazier, also an Olympic gold medalist, was inarguably a fine fighter, a brutal brawler with a stinging left hook; whether he was a usurper of Ali’s rightful crown or a legitimate world champ would be decided in the ring. The two men pummeled each other from the get-go, and the heavy action seemed to wear on Ali. At times he rested against the ropes, and in the 15th and final round he was sent to the canvas by a mighty left. Frazier won the fight by unanimous decision and was well satisfied with the accomplishment. Ali “had a lot of mouth, and his lips got in the way of his hands,” Frazier told Hauser years later. “But I shut his mouth. Yes, I did.”

Shortly after his loss to Frazier, Ali won a more important fight when, on June 28, 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court, ruling unanimously in United States v. Clay, overturned his draft-dodging conviction. As if in celebration, he went on a 10-bout winning streak before being beaten in a split decision by upstart Ken Norton. Ali avenged that result with his own split-decision win in the rematch, and avenged his loss to Frazier when, on January 28, 1974, the two returned to Madison Square Garden. Ali won that decision unanimously after 12 rounds.

Why was the bout slated for only 12 frames rather than 15? Well, because neither man was champion (title bouts are routinely scheduled for 15 rounds, while other fights might be 10 or 12). A year earlier, Frazier had been stopped cold in the second round by the enormous George Foreman. Foreman had dismissed Norton in two rounds as well.

Now Ali had earned the right to face this twenty-five-year-old titan.

Most boxing observers figured the bout versus Foreman was to be the inglorious swan song for the thirty-two-year-old Ali.

They were only hoping he’d survive.

PHOTOGRAPH © HARRY BENSON 1974

Ali with his mother, Odessa, and wife, Belinda, in 1974.

BOB GOMEL/THE LIFE IMAGES COLLECTION/GETTY

THESE ARE TWO SCENES FROM 1964. In March, Malcolm X snaps away from behind a lunch counter in Miami, taking a picture of the new heavyweight champion of the world, the recently renamed Muhammad Ali. (Actually, the day after the Liston fight, the boxer adopted a temporary name, Cassius X, before announcing on March 6 that Elijah Muhammad had bestowed upon him the soon-to-be-famous name, which means “praiseworthy one.”) The rift that grows between Malcolm and Muhammad this year is hurtful to Malcolm when Ali sides with Muhammad; Malcolm will be assassinated on February 21, 1965. The picture below was taken later ’64, in November, as Ali and his wife, Sonji, take a stroll in Boston. Their first date had been at a Nation of Islam fund-raiser that July, an assignation that went so well that Ali proposed on the spot. There are two things about this photograph that are interesting in light of what Sonji has said contributed to the dissolution of their brief union: her fashionable knee-length coat (hardly standard garb for Muslim women) and the looming presence, behind her left shoulder, of their Muslim chauffeur. Once Ali converted, the Nation of Islam was ever present in his life. This was fine with Ali but not with Sonji.

FRED KAPLAN/SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

THOMAS HOEPKER/MAGNUM

FOR MUCH OF AMERICA IN THE MID-1960s, pictures such as these existed somewhere between the foreign and the frightening. Above: In 1966, Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad speaks with Ali in Elijah’s Chicago home.

ROGER MALLOCH/MAGNUM

Also in 1966, Louis Farrakhan with Ali at a Nation of Islam meeting. Contemporaneous notes found on the backs of certain photographs found in the LIFE Picture Collection refer to events like these as supremacist rallies, and one of those notes bothers to say, “Muhammad, leader of Black Muslims, preaches hate. Muhammad has become a ‘father’ to Clay.” The quotation marks around the word father represent, lest the point be missed, a pronounced sneer—as does, of course, the use of the name Clay, who now goes by the name Ali.

THOMAS HOEPKER/MAGNUM

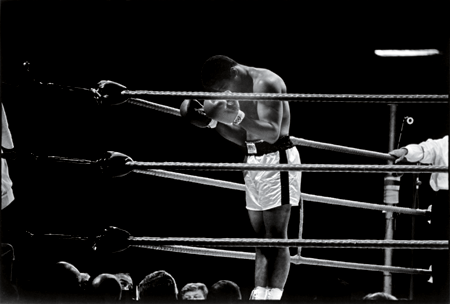

In the ring, the fighter, then aged 24, prays to Allah before scoring a victory against Brian London, 32, at a minute and 40 seconds of the third round in August 1966 in London, England. As said earlier, many Americans were chilled by these images. Ali, by contrast, held that “Followers of Allah are the sweetest people in the world . . . They don’t tote weapons. They pray five times a day.” He believed this sincerely and would remain a Muslim for the rest of his life.

PHOTOGRAPH ©HARRY BENSON 1964

ALI LOVED MUSIC AND, BELIEVE IT OR NOT, HAD a brief fling at a singing career in the 1960s. He was better suited to the listening end, as here at home (above) not long after claiming the heavyweight crown, and in Las Vegas in November of 1965, flirting with the women at a record store during a break in training (below). He was in Sin City to prepare for a title defense against former world heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson, who had been deposed by Sonny Liston. Patterson, a theretofore gentlemanly competitor, upped the ante in anticipation of the bell when he said, “Cassius Clay is disgracing himself and the Negro race.” That comment certainly cut deep, but more damaging still, surely, was the great Joe Louis saying at the time that Ali was “unfit” to hold the title. Louis, the former heavyweight champion known as the Brown Bomber, was considered by many the greatest fighter ever and was an idol in the African American community roughly equivalent to Babe Ruth. The boxing establishment and even fellow blacks were turning on Ali. His response was to lash out with his fists. He punished Patterson mercilessly for round after round before laying him low with a technical knockout in the 12th round. He admitted afterward that the extent of his savagery was due to Patterson’s refusal to call him by his name—which, he pointed out yet again, was Ali.

LEE BALTERMAN/SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

TED POLUMBAUM/NEWSEUM COLLECTION

SONNY LISTON HAD CLAIMED, IN REFUSING TO COME OUT for the seventh round in the first bout, a shoulder injury. The subsequent suspicion that the fight had been thrown caused many boxing authorities to insist upon a rematch, and this was scheduled for late 1964 in Boston. But Ali suffered a hernia strain while training and was hospitalized. Here, his mother combs his hair during a visit. The fight was eventually rescheduled for an arena in the small Maine town of Lewiston.

HERB SCHARFMAN/THE LIFE IMAGES COLLECTION/GETTY

ON NOVEMBER 2, 1964, ALI HAS RECOVERED FROM his hernia surgery and is back hitting the bag in preparation for the Liston rematch. The man watching the workout is not an associate of Angelo Dundee’s but, rather, Stepin Fetchit, the comedian and film actor. He, too, converted to Islam in the 1960s, and he struck up a close friendship with Ali. Below is the beginning of the end of the second Clay-Liston fight. We say “beginning of the end” because the conclusion of this bout was a confused, drawn-out affair—and stands as one of boxing’s most controversial incidents. Just two minutes had elapsed in the first round when Liston went down; few in the crowd of 2,434 who were jammed into Lewiston’s small arena, including those at ringside, saw the punch that had floored him, although film replays will indicate that Ali had connected with a quick right. Even the champ didn’t act like he had delivered any kind of knockout blow. He refused to move to a neutral corner and stood over Liston, glowering and shouting. The referee, former world heavyweight champion Jersey Joe Walcott, was confused by the chaos, and 17 seconds passed before Liston, back on his feet, started to throw punches again. But then Nat Fleischer, publisher of the boxing magazine Ring, shouted at Walcott from ringside that Liston had been down for longer than a 10 count. Walcott declared a first-round knockout, and pandemonium ensued.

AP

Immediately there were suspicions that Liston had thrown another fight, perhaps having bet against himself so he could pay off his underworld creditors. Years later, Liston, in an interview, told boxing writer Mark Kram that he had taken a dive because he feared reprisals from extremist Black Muslims. No corroboration of any threats has ever come to light.

THOMAS HOEPKER/MAGNUM

ELIJAH MUHAMMAD HAD HEADQUARTERED THE Nation of Islam in Chicago, and so that is where Ali relocated; these three photographs were taken in the Windy City in 1966. Ali gets a trim (above) and (below) a love tap from local legend Johnny Coulon, the world bantamweight champion from 1910 to 1914. Coulon, known as the Cherry Picker from Logan Square, followed up his boxing career by training hundreds of fighters at Coulon’s Gymnasium on the South Side; at about the time this picture was taken, the five-footer could still leave a ring by leaping over the ropes and could walk the length of the gym on his hands. He died in 1973.

THOMAS HOEPKER/MAGNUM

THOMAS HOEPKER/MAGNUM

His first marriage now on the skids, Ali flirts with Belinda Boyd in the bakery where she works. A year later, she would become the champ’s second wife and change her name to Khalilah Ali. There was a behind-the-scenes development in Chicago in 1966 as well. When Ali’s contract with the Louisville Sponsoring Group expired, he chose Elijah Muhammad’s son Herbert to manage his career, which Herbert did until Ali retired. To return to tonsorial topics for a moment: In Chicago, Ali was a customer in good standing at the Hyde Park Hair Salon, a pillar of community life at the corner of East 53rd Street and South Harper Avenue. In 1985, a young political organizer arrived in town and chanced into the barbershop. Barack Obama, too, became a regular at the salon, dropping in on an almost weekly basis for 20 years. The establishment was forced to relocate in 2007 when the University of Chicago sold the building in which it was housed to a commercial developer.

BETTMANN/CORBIS

TROUBLE BREWING: ON APRIL 27, 1967, A MONTH after his most recent successful title defense, Ali loses in federal court in Houston when a judge tosses out his last legal effort to avoid being drafted into the Army. As he gazes skyward upon leaving the courthouse, he knows he will refuse to step forward when called at the following morning’s induction ceremony, which will lead to prosecution by the Justice Department and instantaneous banishment by boxing’s governing authorities.

BETTMANN/CORBIS

FROM THE SPRING OF 1967 UNTIL THE AUTUMN OF 1970, ALI WAS TO be denied the ring, but he could not be completely kept from the spotlight. He showed up at peace rallies, including one in San Francisco in April 1968, where he was offered a token gift of flowers from a few of the estimated 12,500 people who marched to San Francisco City Hall to culminate a week-long draft protest. Ali later drew boos from some in this assembly when he spoke of the Black Muslim belief prohibiting racial intermixing. Such views were more readily accepted by audiences like the one at the annual convention of the Nation of Islam in February 1968, where Ali’s oratorical skills were featured (below, with Elijah Muhammad listening). At this time, any given American’s opinion of Ali was almost entirely dictated by his or her political position, and it is impossible to fully appreciate these many years later the virulence of the criticism leveled at him. The governor of Illinois, where Ali lived, considered him “disgusting,” and the governor of Maine, where Ali had fought Liston, stated that he “should be held in utter contempt by every patriotic American.” Ali was unwavering in the face of such attacks and never considered capitulation. “I’m giving up my title, my wealth, maybe my future,” he told Sports Illustrated in 1967. “Many great men have been tested for their religious beliefs. If I pass this test, I’ll come out stronger than ever.”

BETTMANN/CORBIS

UPI/CORBIS

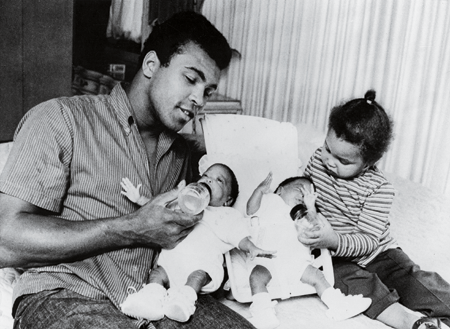

THERE WAS TIME TO ENJOY THE HOME FRONT. In 1970, daughter Maryum helps Dad feed the twins, Rasheeda and Jamillah.

HULTON/GETTY

Ali trains in 1971 with the three girls. Four times married during his lifetime, Ali obviously had issues at various times as a husband, but by accounts he was a caring, if often absent, father. Hana Yasmeen Ali, third youngest of his nine children, was very close to her father—she helped him write his memoir The Soul of a Butterfly—and told Beliefnet.com in an interview: “My dad was gone a lot. So when he was home, my dad gave us 100 percent of his attention. There was never a time when we were shunned, quieted or asked to leave the office. We went everywhere with him. I’m grateful for the time we had. He was a great father because we felt love, and that’s the most important thing.” Ali was of course able to spend more time with his kids during his exile from sport, but by the time these photos were taken, that situation was changing. The Vietnam War had, since Ali had first refused induction, become much more unpopular in the U.S., and there had been a thaw in boxing’s attitude toward Ali. His return to the ring would, in fact, come even before the Supreme Court exonerated him, declaring that his opposition to military service was indeed a product of his religious principles.

JOHN SHEARER/LIFE/THE PICTURE COLLECTION

IT WAS DUBBED THE FIGHT OF THE CENTURY even before the bell was rung. There was reason for this, since the scheduled bout presented a wholly unprecedented matchup: two undefeated heavyweight champions of the world. Ali, who had lost his crown not to a boxer but to men in suits, sported a professional record of 31–0 with 25 knockouts. The titular titlist Joe Frazier’s line read 26–0 and 23 KOs. And then there was all the subtext: the “draft-dodger” versus the presumed patriot; the “black supremacist” against the champion without agenda or complaint; the loudmouth opposing the modest man; the Louisville Lip mixing it up with Smokin’ Joe. For some, particularly in white America, this was nothing less than a sinner fighting a saint. As these LIFE covers (on the pages that follow) indicate, few stories in the country were larger in the waning weeks of 1970 and the first ones of ’71 than Ali’s comeback and his anticipated showdown with Frazier. Ali, reborn as a boxer but with a lingering bitterness lending a harder edge to his personality, took his prefight shtick to new depths; he chided Frazier in a manner that was even meaner than that with which he had gone after Liston. As mentioned earlier in these pages, Frazier admitted years later that Ali’s words were wounding, but at the time he was forced to play along (the staged photo that opened this section being a glaring example) in order to keep the drumbeat loud in the lead-up to the fight. During the hours just before the March 8, 1971, set-to in New York City, that drumbeat was deafening—not only in Madison Square Garden but across the land. In the arena, all manner of celebrity was present, two of them, the writer Norman Mailer and the singer-turned-photographer-for-a-night-so-he-could-get-a-ringside-seat Frank Sinatra, were on assignment for LIFE. Others were there as much to be seen as to bear witness. Elsewhere, people packed movie theaters coast-to-coast to watch a closed-circuit broadcast, with Burt Lancaster providing color commentary behind Don Dunphy’s blow-by-blow. In Chicago, fight fans tried to wreck the theater when they were told the fight wasn’t coming through. There would be riots this night in many other American cities—all because of a prizefight.

PHOTOGRAPH BY GORDON PARKS. COURTESY OF ©THE GORDON PARKS FOUNDATION

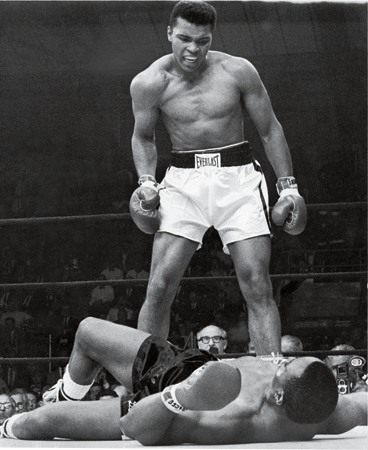

NO BOXING MATCH COULD LIVE UP TO THE ferocious hype, but this one very nearly did. Ali was a mite slower than he had been before his ban, but only a mite. His elegant gifts were on display early as he landed fast jabs to Frazier’s hulking form, meanwhile staying relatively clear of the champion’s storied left hook. But that hook landed in the fourth, and Ali, against the ropes, took severe punishment. He rallied in the next several rounds, and as kids across America stayed glued to their transistor radios to hear the read-back of the action after each round finished, the outcome was anyone’s guess. And yet, Ali, who had trained long and hard before the fight (above), seemed to be tiring, a fact confirmed in the 11th round when Frazier landed a massive blow that staggered his foe. Frazier kept up the momentum, and it seemed that if the tide wasn’t turned in the 15th and final round, he would retain his title. In that round, early on, the left hook was unleashed yet again, and Ali went down. The sight of this superhuman on the canvas (below) was stunning to fight fans. Then Ali rose and finished on his feet. None of Ali’s backers could dispute the unanimous decision in favor of Frazier, though all were left to wonder what might have been had these two met a couple of years earlier. One thing seemed certain: They would meet again.

FRED MORGAN/NEW YORK DAILY NEWS/GETTY

AP

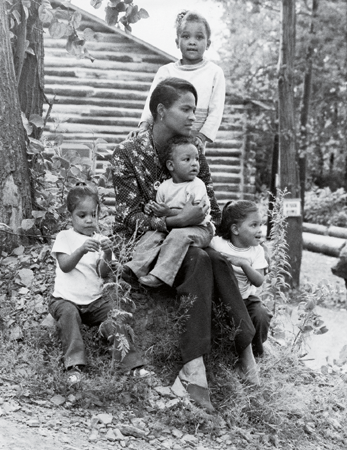

CASSIUS CLAY’S LIFE WAS RELATIVELY STRAIGHT-FORWARD: Eat, sleep, train, brag, box. In this second act of the man’s sporting career, the day-to-day was more complicated. The photographs on these pages, taken in 1972 and ’73, well illustrate the three principal facets of Ali’s existence at the time. Here we see two pictures taken on the grounds of a training camp that the fighter has just purchased for $200,000 in Deer Lake, Pennsylvania. (“The only log cabin gym in the world!” Ali enthused.) He bought the camp so that his family, now living outside Philadelphia, would be nearby and could visit him often as he went about his work. Above: Mom Khalilah (formerly Belinda) sits surrounded by her brood; Muhammad Jr. is in her lap, daughter Maryum is standing, and the twins are Rasheeda and Jamillah. Above: While Dad takes a break, he has a young visitor. The third element of Ali’s life, along with his roles as father and professional athlete, concerned his faith.

©1978 GUNTHER/MPTVIMAGES

UPI/CORBIS

In early January 1972, he prays inside the Holy Mosque in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, during a New Year’s pilgrimage to the spiritual center of the Muslim world. After visiting the Prophet Muhammad’s tomb in Medina, Ali said that he had become convinced while there that he could defeat Joe Frazier if they met in a rematch. So as we see, each aspect of Ali bled into the next.

NEIL LEIFER/SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

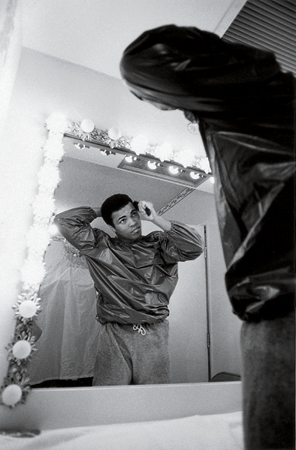

ALTHOUGH HE HAD LOST A FIGHT, ALI WAS BACK in the limelight; he had regained his status as an American celebrity of the highest order. As such he had a responsibility to look good, and he always did. Above, wearing a sauna suit while fixing his hair in the dressing room before his successful fight versus Joe Bugner at Caesars Palace Hotel in Las Vegas in February 1973. Below: Later that night in the ring, he is helped by trainer Angelo Dundee. Ali is wearing a robe given to him by Elvis Presley, proving, perhaps, that what’s begot in Vegas, stays in Vegas. Or maybe that: What was once the King’s, is still the King’s.

NEIL LEIFER/SPORTS ILLUSTRATED