Nature and Time

Almost the whole appeal of the little medieval spring song we saw as our first example of nature poetry comes from its rhythm. Here I have marked the “silent e’s,” which were pronounced (“uh”) in the Middle Ages, so that the original rhythm can be heard:

ANONYMOUS

The Cuckoo Song

Sumer is icumen in,

Lhudè sing, cuccu!

Groweth sed and bloweth med

And springth the wudè nu.

Sing, cuccu!

Awè bleteth after lomb,

Lhouth after calvè cu,

Bulluc sterteth, buckè verteth —

Murie sing, cuccu!

Cuccu, cuccu.

Wel singès thu, cuccu.

Ne swik thu never nu!

At first, as we expect in a simple ballad quatrain (a four-line stanza with alternating four-beat and three-beat lines), a four-beat line (“SUmer IS iCUMen IN”) is here followed by a three-beat line (“LHUde SING, cuCU!”), and another four-beat line is followed by a three-beat line, all of them about the renewing of vegetation. But to our surprise, an unexpected three-beat echo-line is added as a fifth line — “Sing, cuccu!”

Then the poem starts up again. Naturally, we expect another 4 / 3 / 4 / 3 pattern, and we find it, yet this second quatrain is not about vegetation but about the renewing of animal life (ewe and lamb, cow and calf, bullock and buck). We might even expect another echo-line, and we receive it — “Cuccu, cuccu.” But this is followed by another surprise — two more three-beat lines, a little congratulation to the harbinger of spring: “Wel singes thu, cuccu. / Ne swik thu never nu!” The lilt of the whole makes us recognize it as a song, even though we find it in printed form.

Besides its rhythmic shape, then, this little two-stanza poem has exhibited a logical shape, separating the vegetative springing of seed and meadow and wood (stanza 1) from the animal springing of bullocks (stanza 2), and it has also made a pleasing alternation between description (“Sumer is icumen in”) and direct address (“Sing, cuccu!”). It has even displayed another shape: in both stanzas some verbs precede their nouns (“Groweth sed,” “Lhouth after calve cu”) and some do not (“Sumer is icumen in,” “Bulluc sterteth”). These changes make for unpredictability, and therefore pleasure, since we derive pleasure in poems, just as in life, not only from pattern but also from the interruption of pattern. If everything were unpredictable we would have chaos, but what we usually find in a good poem is the unpredictable within an overarching purposiveness.

Dave Smith’s poem on spring uses one of the oldest European lyric forms, that of the sonnet. Smith’s sonnet is a hybrid one, with a Shakespearean rhyming ababcdcd octave and a Petrarchan sestet, efefee:

DAVE SMITH (b. 1942)

The Spring Poem

Every poet should write a Spring poem.

— LOUISE GLÜCK

Yes, but we must be sure of verities

such as proper heat and adequate form.

That’s what poets are for, is my theory.

This then is a Spring poem. A car warms

its rusting hulk in a meadow; weeds slog

up its flanks in martial weather. April

or late March is our month. There is a fog

of spunky mildew and sweaty tufts spill

from the damp rump of a back seat. A spring

thrusts one gleaming tip out, a brilliant tooth

uncoiling from Winter’s tension, a ring

of insects along, working out the Truth.

Each year this car, melting around that spring,

hears nails trench from boards and every squeak sing.

Although Smith, in homage to Shakespeare’s spring sonnets (“From you have I been absent in the spring,” etc.), has given his spring sonnet a Shakespearean octave, he has not divided his sonnet neatly, in terms of thought-units, into three quatrains and a couplet, as Shakespeare usually did. Instead, Smith’s poem begins as a reply to the remark by Louise Glück, couching its reply in stern theoretical language about proper and adequate verities. It then announces its own existence: “This then is a Spring poem.”

The rest of the poem is description: an actual present-tense description of the rusting car, followed (in the closing couplet) by a habitual-present-tense description of what happens “each year,” reassuring us that the previous present-tense process has happened before and happens, in fact, every year. But there is one odd moment in the description of weeds, fog, mildew, tufts, back-seat spring, nails, and boards. It is the phrase about the insects who gather on the metal spring: they are “working out the Truth.” The word “truth” is the Anglo-Saxon form of the Latinate word “verity” (used earlier in line 1 in the plural, “verities”), so we know that the insects are experiencing “proper heat and adequate form” and are stand-ins for the poet seeking his verities. As the metal tooth of the spring uncoils, so the weeds and the rest of nature are uncoiling from winter tension, and the poet has to follow along that uncoiling motion, tracing the path of truth as the insects trace the new path afforded them by the newly sprung spring.

From the end of line 4 through line 12, each line spills over into the next one as the scene uncoils before us. Nothing is end-stopped; everything is growing and expanding. (Poems usually indicate a pause at the end of a line either by a break in thought or by the use of a comma, a period, or some other mark of punctuation; when lines “run over,” we are to infer an ongoing rush of thought or feeling.) The last two lines of Smith’s poem, though, because they tell us what happens “every year” instead of what is happening “now,” are a neat couplet; they represent not discovery but summary. Smith has given us first the theory of the spring poem, then the spring poem in action, and finally the spring poem in habitual summary, showing us his three responses to Glück’s demand — “I know the theory, I know the thing itself, and I know it happens every year.” He also shows us that he is aware Shakespeare did it first, while refusing, as a Modernist, to follow the Renaissance neatness of the four Shakespearean separate thought-units, one for each quatrain, one for the couplet.

Keats’s sonnet on the human seasons is written in imitation of Shakespeare, meaning that it has four quatrains and a couplet. Spring happens in quatrain 1, summer in 2, autumn in 3, and winter in the couplet; we can see Keats’s orderly arrangement at work. Since not only this procession of the four seasons but also its analogy to human life (from spring-youth to winter-old age) are all predictable once the subject is decided upon, how will Keats make his (known in advance) process aesthetically interesting?

JOHN KEATS (1795–1821)

The Human Seasons

Four seasons fill the measure of the year;

Four seasons are there in the mind of man.

He hath his lusty spring, when fancy clear

Takes in all beauty with an easy span:

He hath his summer, when luxuriously

He chews the honied cud of fair spring thoughts,

Till, in his soul dissolv’d, they come to be

Part of himself. He hath his autumn ports

And havens of repose, when his tired wings

Are folded up, and he content to look

On mists in idleness: to let fair things

Pass by unheeded as a threshold brook.

He hath his winter too of pale misfeature,

Or else he would forego his mortal nature.

First of all, Keats doesn’t speak of the seasons of the human body — doesn’t say, “Man has his spring of youth, his summer of maturity, his autumn of decline, and his winter of death.” That cliché was too well known. He decides to put the seasons inside man’s mind. Does the mind, like the body, have seasons? And if so, what are they like (since the mind, in the ordinary sense, does not grow old)? Briefly put, what Keats says is that in youth the mind finds an easy pleasure in spanning the whole world, absorbing everything beautiful. In mental summer, man reconsiders the “fair . . . thoughts” of his spring, redigesting them till they dissolve in his soul and become totally internalized, part of himself. During his mental autumn, he rests, folds his wings, and doesn’t try to see everything — he is “content to look / On mists in idleness.” At this stage, he allows fair things to “pass by unheeded,” as a cottager might fail to notice the brook that flows by beyond his threshold. What does the man look on in winter? Not “all beauty,” not “fair things,” not even “mists” — rather, he looks on “pale misfeature.” Why must he look on the diseased and the deformed? Because otherwise, he would “forego his mortal nature.” He would forget that he, too, must grow pale and die, if he looked only on the beautiful or the misty.

This is a brief summary of a complex poem, but it is enough to show the rapid progress of the Keatsian seasonal sketches — the winged fancy of spring, the cud chewing of summer during the pondering of beauty in the soul, the ports and havens for man’s autumn migration, the folding of his tired wings among the mists of uncertainty, the threshold brook passing by unheeded outside the house of (as Keats called himself) the “spiritual cottager.” Keats’s poems often lead us along by a succession of such descriptions. Without the unexpectedness of all these lightly drawn images, the procession of the seasons might be too predictable. And Keats lets each of the first three seasons slip into the next almost imperceptibly, imitating the way of nature. Only winter is unmistakably set apart in the couplet, as misfeature replaces feature.

In Chapter 1, we looked at Shakespeare’s three models of life in Sonnet 60: the steady-state model of successive waves in which each moment of life resembles its predecessor and its successor; the rise-and-eclipse-of-the-sun model that sketches a catastrophic view of life; and the third, worst, model, in which we do not even have time to grow before we are scythed down. This structure in itself would have seemed sufficient to many poets. In fact, it would have seemed too much. Often, poems offer only one model of whatever they are discussing. But Shakespeare found it irresistible, very often, to let each of his quatrains set up a model different from those set up by the others. The intellectual tension thereby generated — “Is life a steady-state procession? Or a single long climb and fall? Or nothing but successive and premature annihilations?” — involves the reader strongly in the progress of the poem:

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE (1564–1616)

Sonnet 60

Like as the waves make toward the pebbled shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end,

Each changing place with that which goes before,

In sequent toil all forwards do contend.

Nativity, once in the main of light,

Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crowned,

Crooked eclipses ’gainst his glory fight,

And Time that gave doth now his gift confound.

Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth,

And delves the parallels in beauty’s brow,

Feeds on the rarities of nature’s truth,

And nothing stands but for his scythe to mow.

And yet to times in hope my verse shall stand,

Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.

Each of Shakespeare’s three models of Time is a mini-poem in itself. The first model displays itself in balanced ceremonious full uninterrupted lines, like successive waves, making its analogy calmly, as a sermon might:

Metaphor (in simile-form) |

Like as the waves . . . shore, |

Literal truth |

So do our minutes . . . end, |

Elaboration |

Each changing . . . before, In sequent toil . . . contend. |

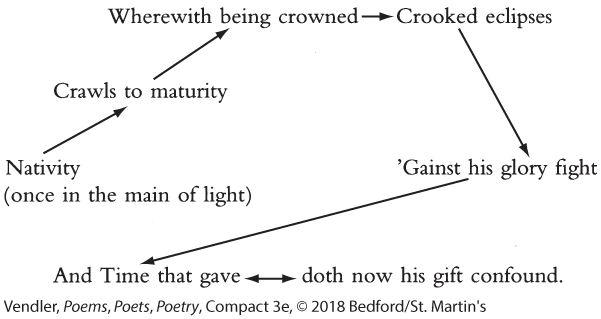

The next model is far more troubled, and its pace is charted by its governing words in cr: “crawls,” “crowned,” “crooked.”

We see nativity crawl up to crowning, then crookedness fight it to death. Time gives on the left, takes away on the right. This is what we think of as the tragic model embedded in those of Shakespeare’s plays that show the rise and fall of a character like Macbeth or Othello. It is completely different from Shakespeare’s steady-state model in quatrain 1.

Shakespeare’s third model consists neither of steady-state waves nor of rising and eclipsed sun. It shows us a drastic speedup in the rate of extinction. It took three lines for the sun to be extinguished; now the deaths occur at the rate of one per line for two lines, and then several per line:

Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth,

And delves the parallels in beauty’s brow,

Feeds on the rarities of nature’s truth,

And nothing stands but for his scythe to mow.

These destructions take place with appalling rapidity, but, what is worse, the way they are related by the syntax of the clauses puts death before lived life. Transfixing precedes flourishing, wrinkles (delved “parallels”) precede the appearance of the beautiful brow, devouring precedes the growing of the rare items in nature’s garden. Finally, life itself is seen to exist for scything, and for that alone: “Nothing stands but for his scythe to mow.” The poet Gerard Manley Hopkins was later to say bitterly, remembering this line, that man was born for death: “It is the blight man was born for.”

Shakespeare’s three mini-poems, three incompatible models of life, have now been sketched in his sonnet. They are all about Time, and how nothing stands. The couplet, in revenge, shifts from “Time” to “times,” and makes them “times in hope” — that is, the envisaged future. The couplet also shifts from “nothing stands” to something standing. In future times (“times in hope”), when the organic world has died, the inorganic world of art, which the scythe cannot mow down, will stand:

And yet to times in hope my verse shall stand,

Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.

This boast might seem to vanquish Time, if the poem did not end with the hand of Time itself, characterized by an adjective — “cruel” — which opens with the same cr- of doom that we remember from the tragic series “crawls,” “crowned,” “crooked.” “Cruel” comes from the Latin cruor, “blood” — and Time’s bloody hand is set over against the “hand,” or handwriting, that creates verse praising worth. It is something of a standoff — but even that is a victory for the rarities of art’s truth. After the three competing models of natural life, each more destructive than the last, Shakespeare has closed his sonnet with a model of the endurance — not forever, but at least to “times in hope” — of his verse.

This second look at our original poems suggests that one can’t fully understand a poem until one sees the various shapes into which meaning has been arranged. We have seen steady-state shapes and shapes of increase and decrease; shapes of contrast and alternation; shapes of series, both internally consistent and inconsistent; shapes of pointed metrical emphasis, of space and time. There is no lack of shapes for poets to imitate — every human action conducted over time offers such a shape, of success or failure, of stasis or catastrophe, of contest or conciliation. The dynamism of such shapes gives dynamism to poetry.