In mid-summer 1863 the end appeared near for the Confederate States of America. Lee had returned from Gettysburg, his army mauled and shaken. Grant had captured Vicksburg; the River Mississippi ran ‘unvexed to the sea’. In the crucial middle ground in Tennessee, Union General William Rosecrans stood poised to advance on Chattanooga, the gateway to the Confederate heartland.

The commander-in-chief of the Confederate military, President Jefferson Davis, reassessed strategic options. He invited his most trusted general, Robert E. Lee, to Richmond for a conference. Lee favoured another try in Virginia. His senior Lieutenant General, James B. Longstreet, disagreed. Longstreet wrote: ‘I know but little of the condition of our affairs in the west, but am inclined to the opinion that our best opportunity for great results is in Tennessee.’ Longstreet’s ignorance of ‘affairs in the west’ was an affliction infecting the entire Confederate high command. Congressmen representing the western Confederacy charged that the Davis government overly ignored the west and concentrated too much attention and resources in Virginia. They maintained that in consequence the Mississippi River had been lost. More recently, General Braxton Bragg, the commander of the Army of Tennessee, had been manoeuvred out of Tennessee. But proponents of a western strategy lacked Lee’s stature. As a Virginian, Lee, in turn, had great difficulty in looking beyond his beloved state’s defence, and as a consequence his fixation on Virginia dominated the strategic mentality of the government in Richmond. Then came Gettysburg.

Following that terrible defeat, the western lobby gained Davis’ ear. The government paid attention when Longstreet proposed going on the defensive in Virginia so as to allow one infantry corps to be transferred west to Tennessee. Longstreet even hinted strongly that Bragg lacked the confidence of his men and that he, Longstreet, should go west to replace him. This step was more than Davis could accept. Instead, Davis asked Lee if he would take command in Tennessee. Lee was reluctant, and upon further reflection Davis too questioned such a transfer. Lee held a mastery over the Federal generals who dared to invade Virginia. His skill would be particularly needed if his army were weakened by the transfer of substantial forces to Tennessee. Looking disaster squarely in the eye, Davis embarked upon a colossal strategic gamble: he would reinforce Bragg by stripping forces from all the other major Confederate armies. Thus strengthened, Bragg would try to destroy Rosecrans’ army and reverse the tide flowing against the Confederacy. Longstreet would go west with two divisions, not as a replacement for Bragg, but to help him regain Tennessee. As Longstreet mounted his horse to depart, Lee said, ‘Now, general, you must beat those people out in the West.’ Longstreet replied, ‘If I live; but I would not give a single man of my command for a fruitless victory.’

The Confederate Army of Tennessee was indeed a hard-luck outfit. Following the battle of Shiloh in 1862 the defeated army retreated to Corinth to reorganize. Two events coincided to mark the western army with misfortune: Bragg rose to the top command, and the one-year enlistments ran out. Many who had patriotically volunteered wanted to go home. Instead they found themselves conscripted for the duration. For this injustice they blamed Bragg, although he had nothing to do with the decision. An enlisted man recalls that henceforth, ‘. . . a soldier was simply a machine, a conscript . . . We cursed Bragg, we cursed the Southern Confederacy. All our pride and valor had gone and we were sick of war.’

A charismatic leader could have overcome such attitudes, but when Bragg began to impose his stern discipline on the unhappy ranks their morale plummeted. For crimes ranging from desertion and sleeping on guard to departing the ranks for a short visit home, Bragg ordered men to be shot or whipped and branded. He restored discipline – an English tourist, Colonel Freemantle, called this army the best disciplined in the Confederacy – but only at the price of crushing his men’s spirits. They neither loved nor respected him. Furthermore, events would show him to be a poor provider for his mens’ basic needs. Hunger was a constant companion for the soldiers of the Army of Tennessee.

The Battle of Murfreesboro (Stones River) pitted 33,500 rebel infantrymen and gunners against 40,100 Yankees. Each side lost about 12,000 men. This staggering rate of losses – 35 and 30 per cent respectively – was in sharp contrast to those of the battles fought in the east. (US Library of Congress)

Yet they fought with amazing courage. In blundering stand-up fights, most recently at Murfreesboro in December 1862, they traded casualties with their opponents at a rate that was proportionally much bloodier than the more famous battles in the east. It went for nought. Letters to the soldiers from their families under-scored the sense of despair. A family letter of an Arkansas colonel said, ‘It has been a gloomy and ill-boding summer to the Confederate cause and Army. God only knows what is to be the result.’ Indeed, what the soldiers gained on the battlefield seemed to be sacrificed by the strategic incapacity of their leaders.

The command dissension stemming from battlefield defeats tore the army apart. After Murfreesboro Bragg and his top subordinates – most notably generals Polk, Hardee and Breckin-ridge – feuded instead of preparing a defence of middle Tennessee. Even after substantial reinforcements had arrived, the consequences of previous command dissent remained an uneasy spectre in the background. Kentuckian Simon Buckner arrived to command a new corps. He quickly assumed Breckinridge’s role as leader of the implacably anti-Bragg clique. Daniel Harvey Hill replaced Hardee. Hill was irascible and quick to take affront, in other words he was much like Bragg. It was inevitable that the two would have at best an uneasy relationship. From Virginia came Longstreet, never the easiest of subordinates. Longstreet had read about Murfreesboro in the Richmond press and thereby developed a strong bias against Bragg. As if these strong personalities were not enough to cripple Bragg, in August Breckinridge returned. In sum, as the army began the Chickamauga campaign, the anti-Bragg group was near its apogee.

Since the Christmas of 1861 Federal commanders in the west had understood the vital importance of Tennessee. At that time General Henry Halleck had announced that the army’s ‘true line of operations’ required a move through Tennessee. Progress had been slow. The most recent Union advance had been arrested at Murfreesboro. For the subsequent seven months Rosecrans rested and refitted his Army of the Cumberland. Then he launched a cleverly conceived quick-striking offensive that cleared several mountain and river barriers and captured the key town of Chattanooga. Over-confident, Rosecrans allowed his army to become scattered in pursuit. Simultaneously, Bragg received substantial reinforcements.

Bragg planned to attack and overwhelm isolated elements of Rosecrans’ army. His strategy was good but the execution was lamentable. On 11 September 1863 and again on the 13th, Bragg’s subordinates balked and thereby permitted the Union troops to escape. These failures angered Bragg. Worse, the close calls alerted his opponent to his danger. Rosecrans ordered his corps to concentrate. By 17 September Rosecrans’ four corps lay along a 20-mile front on the west bank of Chickamauga Creek. Bragg’s better concentrated army was on the opposite bank. Refusing to relinquish the initiative, Bragg resolved to cross the creek and strike a blow before Rosecrans could concentrate further. He planned to advance against the Union left and thus cut off three Yankee corps from their base at Chattanooga. Rosecrans, correctly divining Bragg’s strategy, ordered forced marches to reinforce his left. On the evening of 18 September the two great rival armies massed on what would become the greatest western battlefield of the war.

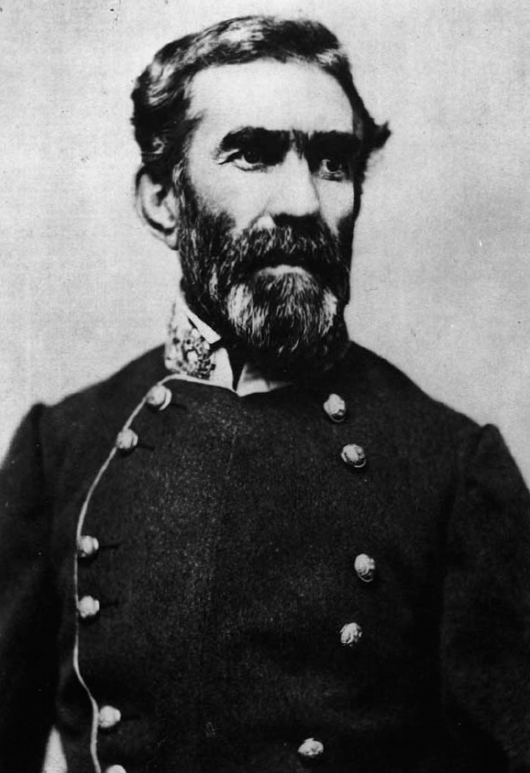

A British visitor described Braxton Bragg, a West Point graduate and Mexican War hero, as ‘the least prepossessing of the Confederate generals’. He was thin, stoop-shouldered and of a cadaverous, haggard appearance. Only his bright, piercing eyes indicated his inner fire. A private observed him and said, ‘. . . his countenance shows marks of deep and long continued study . . . he is a remarkable-looking man, and what I would call a hard case’. A harsh disciplinarian, hated by many of his men, he was unsurpassed in preparing a Confederate army for campaign. Capable of devising sound strategies, he was incapable of earning subordinate loyalty. On the battlefield, when things began to go awry, he proved inflexible. Most of his battles ended in naked frontal assaults upon well-defended Union positions. (Library of Congress)