THE PRIESTS IN MARY’S CHAPEL WORE VESTMENTS OF WHITE AND gold on Whit Sunday 10 June 1549. The Protectorate – Somerset, Archbishop Cranmer and their allies – had banned ashes on Ash Wednesday and palms on Palm Sunday. Every church candle, save two on the altar, was snuffed out by political decree. Now, a new religious service had been commanded. Written in English it reflected the view that Christ was not present, body and blood, in consecrated bread and wine. This was an attack on the heart and soul of Catholic belief. Mary had been arguing that her father’s religious settlement could not be overturned while Edward was a minor. Central to this was the Mass. For Mary the time had now come for an act of defiance. The full Henrician Mass was being celebrated in public at her house of Kenninghall in Norfolk according to the Sarum Rite, said in the British Isles for 500 years.

Across England other congregations listened to the words from the new Book of Common Prayer with growing anger. They had been taught to obey royal decrees as a religious duty, for God had appointed the king to rule over them. Yet their king was only a boy, and what was being asked of them was sacrilegious. The following day, at Sampford Courtenay in Devon, villagers forced their parish priest to say Mass once more. Their rebellion spread rapidly and by 2 July there was violence across the Midlands, the Home Counties, Essex, Norfolk and Yorkshire, while in the west Exeter was under siege. Only ten days later Norwich was also threatened, with an army of 16,000 rebels at its gates, but there it was largely those receptive to the new religious ideas who had joined the rising. The great men who had benefited from the lands confiscated from the church under Henry VIII had continued to expand their estates, and were enclosing the common land that saved the landless from starvation when paid work dried up. ‘The pride of great men is now intolerable, but our condition miserable’, ran the Rebel’s Complaint; ‘We will rather take arms, and mix heaven and earth together than endure so great a cruelty.’

In the end foreign mercenaries were paid to crush the rebel armies. Some 2,500 farm boys were killed in the west and 3,000 in the east, where John Dudley, Earl of Warwick used Germans used to particularly dirty and difficult work. As a percentage of the population the deaths that summer are equivalent to the entire English military casualties of World War II. It left much of the country cowed, but come October Somerset realised he was also under threat from erstwhile allies on the council. They blamed the scale of the risings on the duke delaying the use of force and ignoring advice, even from Henry VIII’s former private secretary, William Paget, who had helped plot his rise to power as the old king lay dying.

The unfolding coup was a frightening experience for Edward, who had just turned twelve. Somerset told the boy that the plotters would kill them both if they succeeded in their plans. Edward was seen riding from Hampton Court to Windsor with his uncle, waving a little sword from his horse, begging those on the roadside, ‘My vassals will you help me against those who want to kill me?’ When the guards came to Windsor to arrest Somerset and entered Edward’s chamber he reacted with terror. He was soon reassured, however, and there were no plans, as yet, to execute Somerset, who was lodged in the Tower. He was merely replaced by a Privy Council now chaired by John Dudley, who would be named Lord President a few months later.1

The son of Edmund Dudley, one of the most notorious of Henry VII’s henchmen, John Dudley was a devoted family man adored by his wife and children. He could, however, also be extremely intimidating. He had clawed his way up the greasy pole in the shadow of his father’s execution at the outset of Henry VIII’s reign and it was later said that he ‘had such a head that he seldom went about anything, but he conceived first three or four purposes beforehand’.2 The Imperial ambassador judged him a pragmatist and hoped the overthrow of the Protector would be good for Mary. She told him doubtfully on 7 November that ‘the councillors have not as yet pressed her or exacted from her anything against her will . . . and so . . . she is awaiting the upshot of the matter, not without apprehension’.3 Meanwhile, at Mary’s turreted house of Beaulieu in Essex on 26 November, she prepared to receive her cousin, Frances Brandon, who was accompanied by her daughters.4

A slim, elegant woman, Frances was the elder daughter of Mary’s late aunt, the French queen, and only a few months younger than Mary.5 She had served in the princess’ household when her eldest child, Lady Jane Grey, was a baby. Mary recalled with gratitude the support Frances’ mother had given Katherine of Aragon against Anne Boleyn. But Frances found the arguments of Swiss and German religious reformers inspiring and she was amongst those who most welcomed the religious changes that Mary opposed. Having carefully erased all mentions of the Pope and Thomas Becket from a Book of Hours she had inherited from her mother, she now found all the images of saints and devotions of the Virgin so distasteful that she would give it away the following year.6 Her daughters Jane, aged twelve, Katherine nine, and Mary Grey, four, were all being raised as what we could now term Protestants and she was particularly close to Jane, who she helped with her studies.7 An exceptionally clever child, Jane was also proving passionate about her faith. According to the Protestant martyrologist John Foxe, Jane even deliberately insulted Mary’s belief in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist while she was staying at Beaulieu.

On the altar in an antechapel, at right angles to the main chapel at Beaulieu, there was the exposition of the Blessed Sacrament: that is, the consecrated host was displayed after the Mass in a golden sunburst stand known as a monstrance.8 For Mary the host was the transformed body of Christ. Jane saw it as nothing more than the idolatrous worship of a piece of unleavened bread. When one of Mary’s servants dropped to one knee in genuflection as they passed the chapel, Jane asked her sarcastically ‘whether the Lady Mary were there or not?’ The servant retorted that she had made her curtsey ‘to Him that made us all’. ‘Why’, Jane commented acidly, ‘how can He be there that made us all, [when] the baker made him?’9

On 29 November, three days after Frances’ arrival at Beaulieu with her daughters, their father, Harry Grey, Marquess of Dorset, was appointed to the Privy Council. Described as ‘an illustrious and widely loved nobleman’, Harry Grey was much admired for his learning and his patronage of the learned. But he had all the arrogance of the ideologue and the Imperial ambassador described him as being without good sense.10 He had never previously been trusted with a council place, and that John Dudley had now given him one was taken, correctly, as a signal that Dudley had decided to base his regime on the most enthusiastic reformers.11 Edward VI, like his mother Jane Seymour, was by nature keen to please, and Dudley had discovered that Edward’s tutors had been successful in raising a reformist prince. An enthusiasm for further reform would help him to gain Edward’s trust. Within a month orders had gone out to destroy all Latin service books. By mid-January the Imperial ambassador was expressing fears that the new regime would ‘never permit the Lady Mary to live in peace . . . in order to exterminate [the Catholic] religion’.12

Over the next few months reform was driven fast and hard, with Harry Grey and John Dudley spearheading action on the council, along with Katherine Parr’s brother, William, Marquess of Northampton. Statutory approval was given for clergy to marry, stone altars destroyed and replaced with simple wooden Communion tables, organs were ripped out of churches and elaborate music expunged, while in Oxford the Edwardian bonfires appear to have consumed nearly every book in the university library.13 Mary also found that she was under attack for continuing to have Mass said publicly in her chapels, but she was determined to hold fast. Who could better defend the Catholic beliefs of her brother’s subjects than the most senior adult royal in England? She could not be as easily disposed of as the peasants of Norfolk and Devon. She had to show courage and hope that one day, soon, her brother would overthrow his erstwhile guardians.

Harry Grey and William Parr were at Edward’s side that Christmas of 1550, when Mary came to court to see the king. At thirteen Edward was growing up and like his father dressed magnificently, favouring reds, whites and violets embroidered with pearls.14 This helped disguise the fact he was small for his age, slightly built and, like Richard III, he had one shoulder distinctly higher than the other. He may have inherited scoliosis with his Yorkist blood. Edward had once told Mary that she was the person he ‘loved best’. But instead of fraternal kisses, Mary was subjected to a tirade, with Edward demanding to know why she still held the Mass in her chapels. Shocked, she burst into tears. This, in turn, prompted Edward to cry. He would have preferred that she understood her duty to him better and that they need not quarrel. He found it painful: that much was obvious to Mary, who was convinced that Edward had been put up to making his comments.

The following year Mary continued to use her influence to defend her father’s religious settlement – and her influence was considerable. To her servants and affinity Mary was a quasi-sacred figure, who cared for them body and soul as their sovereign princess, sitting before them daily under a cloth of estate, in rooms hung with tapestries that boasted her royal lineage. Of Mary’s four grandparents, three had been reigning monarchs and all were the senior representative of their royal house. She was, above all, heir to the throne. In March 1551, when Edward called Mary to Westminster for a further dressing-down, she arrived in London in force ‘with fifty knights and gentlemen in velvet coats and chains of gold afore her, and after her four score gentlemen and ladies’. Each of them carried their banned rosary beads, prominently displayed.15

Mary soon discovered, however, that she had failed to intimidate the regime. Edward would turn fourteen that year, the age at which a boy could marry under common law. John Dudley and the council had decided this would mark his majority. The implication would be that she was no longer defying them, but that she was defying the king. At Easter 1551 several of Mary’s friends were arrested after attending Mass in her house. By July she feared she was on the point of being imprisoned, or even murdered. Matters came to a head in August 1551, just as Edward began attending his first council meetings. Three of Mary’s servants were ordered to go to Beaulieu and prevent other members of the household from hearing Mass. They refused and were duly imprisoned. Mary was obliged, nevertheless, to give way. As she noted, if they arrested her chaplains too she could not hear Mass, however defiant she remained. Mary made it clear, however, that she would lay her head on the block before she heard the Prayer Book service.

Come the autumn the aggressive attacks on Mary began, mysteriously, to recede. The reasons were not immediately obvious, but behind the scenes John Dudley was facing a threat on which he was obliged to focus his attention. Edward had been ill over the summer and, although he had soon recovered, it was a reminder that Mary remained only a heartbeat away from the crown. There was anger amongst the political elite over the way the heir to the throne was being treated. The Protector Somerset, who had been released from the Tower in February 1550, was hoping to take advantage of this to bring Dudley’s regime down. Dudley intended to deny Somerset that support and strike first.

Anne Boleyn’s daughter Elizabeth wore this ring after she became queen.

Katherine Parr, attributed to Master John.

Funeral effigy of Margaret Douglas and four of her eight children.

James VI of Scotland, aged twenty.

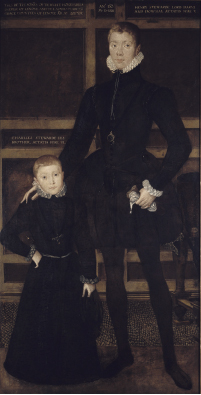

The spoilt, vicious, doomed, Henry Lord Darnley – later King of Scots – and his brother Charles.

During the second week of October the young king was given the shocking news that his uncle Somerset was planning to murder Dudley and Katherine Parr’s brother, William Parr. Edward promptly empowered Dudley further, by creating him Duke of Northumberland, his ally Harry Grey, Duke of Suffolk, and William Parr’s brother-in-law, William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke. William Parr already had the great title of Marquess of Northampton. Five days later Edward saw his uncle arrive at court at Whitehall, noting in his diary that he was ‘later than he was wont and by himself’. Edward then added the chilling comment, ‘After dinner he was apprehended.’ The former Protector was returned to the Tower, and this time he would not be released. Somerset was to be executed early in the following year.16

Mary soon found she was again being invited to court. The pretext was a reception given in November for Mary of Guise, the widow of her cousin James V, who had died in 1542. Mary declined the invitation, perhaps because she feared being asked to attend a religious service with the king. Instead, Edward’s diary records that he sat on Mary of Guise’s right, under a shared cloth of state, while on the other side were his cousins Frances Brandon and Margaret Douglas. Frances was often at court, because her husband, Harry Grey, was regularly at the king’s side, but Margaret and her husband Lennox had also maintained cordial relations with Edward and his councillors. They were discreet about their conservative religious inclinations and Lennox was useful to Edward, running an effective network of spies in Scotland.17 The women dressed to flatter Mary of Guise, in the Scottish style with their hair loose, ‘flounced and curled and double curled’.

Strikingly, the princess Elizabeth was no more present at the reception than her elder sister, Mary. But she made her presence felt when she did appear at court, by dressing so plainly that it was ‘to the shame of them all’.18 Edward had recently received a work promoting modesty of dress in women, and Elizabeth was keen to remind him that, in contrast to Mary, she was the good Protestant princess her reformist governess had raised her to be, as well as (less convincingly) modest and chaste. It did her little good. While Edward noted Lady Jane Grey’s attendance at the reception, he made no mention of his half-sister’s presence on any of the days when Mary of Guise was being welcomed and entertained. It seems he was not encouraged to be any closer to her than he was to Mary.

That Christmas, after Mary of Guise had left, there were further entertainments to be enjoyed at court with plays, masques, tournaments and a tilt on the last day, 6 January, which Edward enjoyed enormously. John Dudley had ensured Edward had been taught to ride and handle weapons, and Edward had begun ‘arming and tilting, managing horses and delighting in every sort of exercise’, although he did not yet take part in the competitions.19 Dudley was extremely astute in his handling of Edward. According to the French ambassador, Edward revered Dudley almost as if he was his father. Yet Dudley was careful to emphasise that, as Lord President of the king’s council, he was only a senior member of a team working for Edward, whom he involved ever more deeply in matters of state.

In March a core of the king’s senior servants began to meet with him each Tuesday to brief him on policy matters. High on the agenda was the work that was about to begin on a new and more radical prayer book, which would rename the Eucharist the Lord’s Supper, have Communion tables brought into the church chancel or nave so people could stand around them as for a communal supper, and where they were given bread in their hands rather than unleavened wafers in their mouths. It would also rewrite the baptism and confirmation service, and remove all mention of prayers for the dead at burial services. Edward’s cousin Margaret Douglas remained at court, but in early April there was a measles and smallpox outbreak and on 7 April she asked permission to return to Yorkshire.20 Even Edward had fallen ill, but happily by the 12th, when Margaret was heading north, Edward was reporting that ‘we have shaken that quite away’, and in the summer Edward was hunting again.

That October, when Edward turned fifteen, a famous Italian astrologer was invited to cast the king’s horoscope.21 He predicted Edward would reign a further forty years and would achieve much. The revised Book of Common Prayer, published in November 1552, was to be followed by the publication of forty-two articles of faith that would become the basis for the Elizabethan thirty-nine articles that today remain the founding beliefs of the Church of England.22 The future would not be untroubled: the country was suffering dire financial problems, stemming in part from the wars of the 1540s against France and then Scotland. Cranmer and Dudley had fallen out over the execution of Somerset and the push for a further confiscation of church assets. But the longer-term prospects were bright: it was, the astrologer assured Edward, all in the stars.