chapter 3

Figures and Forms of Analysis Practice

The process that gradually led to the autonomy of musical art during the past three centuries is now well known. Many scholarly studies have described how the musical work was gradually detached from its various social functions to become a purely aesthetic object (Goehr 1992, Weber 2008). However, the consequences of this phenomenon—notably the simultaneous increase in the importance of musical analysis—have not been thoroughly explored. Indeed, it is difficult to know whether analysis is a symptom or a cause of the new ways of representing and talking about music; it is no doubt a bit of both at the same time.

Historians of musical analysis have long limited themselves, in large part, to studying the scholarly discourse that emerged during the nineteenth century. The 1994 publication of a two-volume anthology conceived by Ian Bent marked a decisive step in renewing the history of musical analysis (Bent 1994). Bent’s work considerably expanded the spectrum of sources deemed legitimate and refused to dismiss early analytical texts as crude ancestors of the specialized studies that proliferated during the course of the twentieth century.

In this chapter, I reconsider the history of musical analysis by expanding upon Bent’s propositions. I additionally suggest that although musical analysis principally concerns the musical text, it also surpasses the work to constitute an artistic activity in and of itself—one with links to many fields of thought and to concrete musical practices, both domestic and public.

Indeed, by the end of the nineteenth century, by which time analysis had imposed itself as an indispensable part of musical practice, it also synthesized a range of earlier practices: the scholarly techniques of philology and hermeneutics promoted by Romanticism as keys to modern knowledge; the older intellectual practice of rationally cutting apart objects of study that dated to at least the seventeenth century; new reading skills resulting from the gradual spread of literacy among European populations; and aesthetic assumptions concerning the superiority of the artist’s perspective in matters of artistic creation, whether in the visual arts, in literature, or among music lovers.

From the second half of the seventeenth century onward, musical analysis was deployed in a variety of contexts: in conceptual elaboration, in support of abstract demonstrations, and as a didactic tool. Jean-Philippe Rameau’s writings reflect this triple use, whether in breaking down the mechanism of the vibrating system (corps sonore) (Génération harmonique, 1737); in response to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s examination of the monologue from Quinault and Lully’s Armide (in which Rameau offered an alternative analysis of the same passage that also defended his own musical theories; Observation sur notre instinct pour la musique et sur son principe, 1754); or in listing useful models for the student composer as he does in the third part of his Traité de l’harmonie, where Rameau reduces the art of musical invention to three intervals from which all the principal chords and progressions of the fundamental bass (basse fondamentale) can be derived, in turn determining the rest of a polyphonic texture (Rameau 1722). In all three cases, Rameau’s analysis reveals the structure of objects by taking them apart, naming the pieces, and explaining the nature of their relationship to one another.

The analytical techniques of these early theorists and polemicists remained more or less marginal until the end of the eighteenth century, when the spread of public concerts for paying audiences and the notion of absolute music led to a significant change in the public’s relationship to musical works, in terms of both listening practices and the kind of discourses the music stimulated.1 This new aesthetic context explains how verbal commentaries on the experience of contemplating masterpieces emerged as the dominant form of analysis during the same period—one to which the press and publishers in general devoted ever-increasing attention.

In this story, the question of listening occupies an essential place. It is certainly the musical practice that shows the most important transformation between the middle of the eighteenth century and the end of the nineteenth century. Since the Renaissance, the appropriation of scholarly music had been passed along through its practical proficiency. The amateur heard the music while doing it, and when he was the spectator of the performance of a piece by others than himself, he appreciated it in reference to his experience as a singer or instrumentalist. The invention of musical analysis at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries answers—among other things—the need to train amateurs and professional musicians to meet the new demands of modern art—namely to appropriate works always more virtuosic that would be presented to listeners less able to play them. The analysis is then necessary not only as an intellectual technique for elucidate musical discourse but also as a tool for the education of sensory practices.

In this chapter, I expand the corpus of analytical texts renewed by Bent, adding documents produced in England and France, as well as some further sources in German. These include articles printed in the press, chapters from teaching manuals, and texts found in concert programs, listening guides, and annotated scores, among others. Some of these sources use the word analysis without designating the meaning that became dominant in the twentieth century, and the word itself is absent from other sources that nevertheless played a role in shaping the term’s contemporary use.2 By showing interest in texts that constitute the overwhelming majority of nineteenth-century analytical production—namely a type of discourse targeting the average reader that gradually became part of the daily life of thousands of amateurs and professionals—this chapter does not propose a general history of the theories of musical analysis, a project that has already been undertaken elsewhere.3 Moreover, scholarly musical analysis, which made up a very small part of the analytical discourse produced from the early nineteenth century to the eve of the First World War, receives very little attention in the following pages. Instead, I focus on ordinary analytical knowledge and on the many ties that linked knowledge with intellectual techniques and practices issuing from other domains, often far removed from the world of music, but that persisted through the entire length of the nineteenth century.

The Origins of Musical Analysis in Philology and Hermeneutics

In the early eighteenth century, Germany became a hot spot from which two techniques for examining texts, in philology and hermeneutics, began spreading throughout Europe. The success of these texts spread beyond intellectual circles; indeed, the entire continent witnessed a twofold shift in linguistic and interpretive practices, ranging from the study of scripture to discourses on art, and from scholarly knowledge to daily artistic undertakings. Musical analysis directly benefited from these tendencies.

Philology deals not with languages in general, as does linguistics, but rather with particular languages anchored in particular places and in enunciative contexts. The dominant scholarly model, known as classical philology, consists in the study of written monuments from antiquity, such as medals, inscriptions, or manuscripts, which are deciphered, translated, and interpreted after there is an evaluation of their reliability (often conducted by comparing different variants of a single text) (Cerquiglini 1999).

During the first third of the nineteenth century, enthusiasm for publishing texts of antiquity led to the creation of permanent institutions (such as scholarly journals, chairs, schools, and seminaries), as well as to long-term editorial projects that often spanned several decades and required considerable means. These projects initially concerned the literary monuments of the Middle Ages, but they were soon extended to musical works of all periods (Heyer 1980, Hill and Stephens 1997). The Bach-Gesellschaft-Ausgabe, begun in 1851 and published by the firm of Breitkopf und Härtel, was the pioneering enterprise in the domain. Breitkopf would go on to play a determining role in future projects, undertaking the publication of the complete works of Handel (1858-), Palestrina, Beethoven (1862-), Mendelssohn (1874-), Mozart (1877-), and Chopin (1878-). The trend soon spread throughout Europe, leading to publication of the complete works of Jean-Philippe Rameau in France (1895–1924), of André Modeste Grétry in Belgium (1884–1937), and of Domenico Scarlatti in Italy (1906–1910). Alongside these monographs were published a series of anthologies, which were the fruits of competitive emulation stimulated by national pride.4 The sacralization of genius so typical of the Romantic period also fed a fascination with the correction of musical texts (Lowinsky 1964, Murray 1989, DeNora 1995). Considered as a whole, however, the major compilations published from 1850 to 1914 show a great deal of variation: although many critical editions include notes and indicate variants, just as many deliver the text without further explanation.

Hermeneutics, on the other hand, was long associated with apologetics or the rational defense of Christianity, a practice that draws first and foremost from Scripture. A close cousin to exegesis, hermeneutics was an interpretive art that sought to establish the true sense of the sacred texts. Friedrich Schleiermacher is known for having borrowed hermeneutics from biblical study as a tool for interpreting other types of texts and, beyond that, as a means for understanding the world in general (Bowie 2005). Thus, hermeneutics became a way to order a path toward enlightenment that could be applied to all manner of objects under study. It also turned out to be an unending process, since the interpreter finds himself engaged, as Friedrich von Schlegel demonstrated in regard to the writings of Boccaccio (1801), in an endless comparison of texts, of works related to the genre of the texts, of genres related to the whole of a national literary production, and so forth (Schlegel and von Schlegel 1801).

The work of hermeneutics gave rise to the impossibility of understanding—indeed, in 1800, Friedrich von Schlegel published an article-manifesto in the revue Atheneum titled “Über die Unverständlichkit”—an essential theme in Romantic aesthetics and the very reverse of the principles of rationalist philosophy (Mueller-Vollmer 2000). This fruitful dilemma led to a form of what came to be known as the hermeneutical circle. The partisans of a properly conducted interpretation held that it was essential to give an essential place to reason in the studies of language and history, whereby no signification or phenomenon can truly be isolated from its relatives. In other words, the subject cannot exist outside the object one wishes to understand. In this way, hermeneutical practice put an end to abstract explanations in favor of a permanently renewed effort to return the text to its context. It affirms the intimate relationship of the author to his language, above and beyond the community to which he belongs or the tradition within which he inscribes himself (yet another manner of extending the celebrated hermeneutical circle).

In substance, hermeneutical reflection gives an essential place to the empirical world which itself is so closely associated with meaning that it becomes impossible to dissociate the interpretation of meaning from the interpretation of the empirical world at large. Hermeneutical thought is also characterized by its a priori assumption of a text’s obscurity, making it necessary to invent appropriate tools for its clarification. Analysis fulfilled this function in Romantic hermeneutics’ program of educating people to read, offering common ground in the propositions of Schlegel, Ast, and Schleiermacher in spite of their other differences.

German musical periodicals created at the end of the nineteenth century played an essential role in applying hermeneutics to music (Bent 1994, 2:14–19). The brilliant essays of E. T. A. Hoffmann, which were soon translated into many languages, have since eclipsed a less sophisticated literature that had found its source in the numerous music reviews published in late eighteenth-century periodicals. Mary Sue Morrow has studied these reviews, which often included musical excerpts and served to police good taste, delivering their verdicts after undertaking a harmonic or formal dissection of the work in question (Morrow 1997, 154–157). These unpretentious texts, which increasingly considered works as a whole, and not only for interest in particular passages, invented analytical methods that would reach hundreds of music lovers and professional musicians (155).

The Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, published in Leipzig under the direction of Friedrich Rochlitz from 1798 to 1848, furnished analytical models that were soon imitated throughout Europe. A well-known article published in the Berliner allgemeine musikalische Zeitung by its director, the critic Adolf Bernhard Marx, gives an idea of how musical hermeneutics had evolved only a few decades after the appearance of the periodicals studied by Mary Sue Morrow (Marx 1826, Burnham 1990). In his review of the first edition of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, which contains no fewer than eight musical examples, Marx strives to extract the meaning of the musical material and its form, using the words Missdeutung (misinterpretation) and misszuverstehen (to misunderstand) to refer to the need to clear up the ambiguities of a text or of working something out through inductive reasoning. According to Marx, to understand the Ninth Symphony, one must not only pierce the mystery of the “artist’s original intentions” but also seek the traces of his human experience in every measure. For Marx, appreciating Beethoven’s music requires both the careful analysis of his scores and an intimate knowledge of his biography, made possible thanks to the then swiftly expanding genre of biographical literature.5 At the end of his explanation, Marx addresses the musician: “Here is what should, before all else, be kept in mind wherever a performance of this great work is being prepared.” Over the course of his article, the whole of musical practice, from the performance to the listener, is strictly ordered in accordance with two closely related texts: the score and its commentary.

A similar phenomenon could be observed in Paris, London, and Berlin, where an enthusiasm for the new relationship with the musical work as encapsulated by Marx in 1826 quickly spread. The musical press began to regularly publish “musical analyses,” with concert reviews that devoted a large part of their coverage to dissecting scores and providing “interpretation”—a term that began to supplant “execution” during the same period (Campos 2014). Its parallel in the art world during the same period is striking: in increasing numbers, art lovers began to master the technical vocabulary of pictorial analysis in preparation for constructing and sharing their judgments with peers who were art connoisseurs (Hamilton 2009).

The beginning of the nineteenth century saw publication of a steadily increasing number of pamphlets and newspaper articles concerning techniques of interpretation. In the art world of this time, interpretation alternated between two complementary ambitions: penetrating the artist’s reasons and understanding the work as a whole. These twin ambitions were the core program for musical analysis as well, regardless of the type of publication, the analytical methods employed, or the place of publication. This program owed its fortune to an ability to respond to new aesthetic needs prompted by the adoption of philology and hermeneutics as general models for artistic practice.

Music Reduced to Text

The history of music created during the long nineteenth century has been presented as a series of aesthetic revolutions and momentous scandals, the most celebrated being the Paris premieres of Tannhaüser in 1861 and Le Sacre du printemps in 1913. Considering artistic practices instead of works reveals a quieter but no less profound upheaval; in this case, it is the disappearance of a fluid conception of the musical experience that prioritized improvisation, in-the-moment ornamentation, and adjustment to the instrumental or vocal means at hand, in favor of a fixed conception of the work that aims, first and foremost, to reproduce the creator’s intentions as faithfully as possible. In other words, music was increasingly reduced to a text to be respected at all costs. In accordance with this, the musical world fell under the influence of what Jack Goody has called “graphocentrism” (Goody 1977).6

Indeed, musical analysis is emblematic of the new way in which works were now being understood, and critics writing for the press were among the first to take up this campaign. In reviews published after an opera premiere, it had become traditional, from the end of the eighteenth century onward, to include what was called an “analyse de la pièce,” or a summary of the plot, as well as commentary on the musical numbers, with the end of the article rapidly touching on the performers or the staging and in general limited to a discussion of the sets and costumes. From the 1830s onward, however, the complexity of certain operas, such as those of Giacomo Meyerbeer, caused music writers to publish not just a series of their impressions as listeners but also a veritable analysis of the score, sometimes accompanied by musical citations.

In a review published after the February 29, 1836, premiere of Les Huguenots at the Opéra de Paris, for example, Berlioz qualified the work as an “encyclopédie musicale,” and alerted his readers that “several attentive listenings are absolutely necessary for the complete understanding of a score of this nature.”7 Remarks on the exceptional demands of the opera regularly turn up throughout the article. To appreciate the elements of the admirable libretto exploited by Meyerbeer, “one must first have had the time to study this immense work in depth, one in which Mr. Meyerbeer has sown musical riches enough to assure the fortune of twenty operas.”8 To gauge the boldness of the Septet of the Duel, the fourth act Duo, or the fifth act Trio, “we once again request time to reflect upon our impressions, to analyse them and understand their causes.”9

Indeed, some of the innovations in Les Huguenots are so great that they caused Berlioz to momentarily lose his senses. In the third act, where Meyerbeer superposes three choruses after having presented them separately, Berlioz writes that, at the moment of superposition, “the ear experiences a sensation comparable to the one produced upon the eyes by an overabundance of light, the ear is dazzled.”10 To resolve this unprecedented difficulty, Berlioz extended his analysis to a second article and two other texts he published in a second journal at the end of the same year, including a new analysis made with the score in hand (Berlioz 1836b, 1836c, 1836d).11

A particularly audacious effect of Meyerbeer’s catches Berlioz’s attention in the opera’s second act: the movement from a D major chord to an andante in E-flat that is played with a particularly original distribution between orchestra and the vocal parts. Taking stock of this passage, Berlioz speaks of “the difference that separates musical impressions as received by the ear alone from those that we perceive by the ear aided by the eyes.”12 He challenges Meyerbeer’s blurred modulations, but concedes that “it is probable that the flaw does not exist for Mr. Meyerbeer; from today onward it will even be less prominent for me because I have read the score, and in future I will hear, like the author, the preparatory chord that he placed in the orchestra and which is impossible to notice without having been warned.”13

In Berlioz’s considerably developed paragraph devoted to aligning the experience of listening with the knowledge drawn from studying the score, he estimates that it is not possible to make an aesthetic evaluation of the new opera before having scrupulously read its text. The double articles of November and December 1836 also bear witness to a new temporality in musical practice. In a world where it was increasingly easy to repeatedly hear works that had entered the repertoire, prevention of sonorous misunderstandings was of capital importance. As creators began to explore uncharted territory with each new work, listening also meant drawing upon preparatory analytical work drawn essentially from score study.

During this period, writing analyses remained the domain of a critical elite consisting essentially of professional musicians: in Paris, men such as Hector Berlioz, François-Joseph Fétis, and Adolphe Adam; in Germany, Robert Schumann and Richard Wagner; in London, the organist and music critic Joseph Bennett, and so forth. Music publishers soon adopted the habit of sending these important figures in the musical trade their orchestral scores or piano reductions in anticipation of premieres, so as to guarantee that the works in their catalogues would be judged in sufficiently serious terms according to the new criteria of analytical appreciation.

Amateur musicians and music lovers were also affected by these new interpretive techniques, because they counted among the readers of the press, but also because they used the new commentary-laden scores that became increasingly popular as the century progressed. The emergence of these publishing innovations can be explained as the conjunction of several factors: composers’ ever-tighter control of their musical gestures and intentions; the sacralization of the text, conferring greater responsibility on the performers; and the arrival of Beethoven’s works, which challenged many musicians who called for guides so as to prepare for their performances.

These published scores with commentary began as brochures meant to be used with the score open on the same table or music stand, as in a back-and-forth movement suggested by the pioneering work of Thérèse Wartel: Leçons écrites sur les sonates pour piano seul de L. van Beethoven (Wartel 1865). In her foreword, Wartel solemnly declares “We live in an eminently analytical century.”14 To fully understand what she considered the indivisible whole of the thirty-two sonatas before playing them, Wartel became familiar with Beethoven’s oeuvre during “a long stay in Germany, during which I, one might say, lived in familiarity with his memory” (x). Wartel also abundantly cites Beethoven before settling down to a critical discussion of the more or less erroneous performance traditions that have obscured the true meaning of the sonatas. She then charges the pianist-reader to copy the structural divisions and expressive suggestions of her essay into his or her score.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, it was no longer possible to count the number of interpreters who were incorporating analytical commentary or technical advice into scores and where the additional information soon occupied more space on the page than the musical text. Raoul Pugno, Édouard Risler, Blanche Selva, or Alfred Cortot annotated the classic masterpieces, armed with the experience and knowledge they had acquired in years of concertizing and teaching.

One of the most representative of these commentary editions is the series conceived by the pianist Georges Sporck. Sporck’s scores are heavily annotated between each system, detailing every episode of the work’s formal structure. In the margins, further notes from the interpreter gloss the remarks already inserted in Beethoven’s score (see figure 3.1). Sporck even conceived a second volume containing information on the history of the work, offering a host of indications on how the music was conceived, analytical remarks, and annotated figures that could be placed alongside the score. Ultimately, there remained not a single measure, not a single note of Beethoven’s score that was not an object of commentary. Alas, the apprentice pianist could be crushed under the textual apparatus that was intended to ease the task of interpretation.

Figure 3.1 Édition moderne des classiques. Sonate op. 27 no 2 pour piano. L. van Beethoven analysée par Georges Sporck

In the space of a century, philology and hermeneutics had taken residence in the heart of daily musical practice. Music became increasingly confused with the score, which could now exist without being played when the critic, but also the instrumentalist or singer, studied it for itself. Even when placed on the music stand, the text with notes now underwent a labor of unprecedented volume. Examined, dissected, endlessly probed, its significance only emerged through an analysis that followed the linear unfolding of performance. The analytical reading of the score competed with the production of sound, becoming a complex technique that every musician was expected to learn and apply with personal conviction.

These analytical practices were not limited to the wealthy or the closed circles of intellectual art lovers. Indeed, the place of music might be compared to that of literature: during the second half of the nineteenth century, when familiarity with the works of the national pantheon of writers played an essential role in the education of children in most European countries from very early age (Howard 2012). Regardless of class, the daily practices of amateurs progressively aligned with their scholarly models.

Analyses for Better Listening

During the nineteenth century, the musical situation was a spectacle defined in terms like those of an exhibition of masterpieces—a musical museum, be it of classic or modern works. Amateurs and professionals alike transformed the most intimate qualities of their perceptive tools in order to best appreciate the “objects on display”; for music, this was in terms of the density of their construction and their relative newness at first performance (Weber 1999, Rehding 2009).

Historical studies of musical listening patterns have been thoroughly renewed in the past thirty years. The many publications on the subject agree that the way audiences listen underwent significant transformation between the end of the eighteenth century and the middle of the nineteenth century. In a well-known study, William Weber characterizes the earlier mode in terms of music in constant competition with other noises and a discontinuous form of listening that was endlessly challenged by other activities—in other words, a form of listening that, by present standards, could hardly be considered listening at all (Weber 1997). Gradually, the practice of reconciling attendance at a concert or opera with other social and worldly demands was replaced in favor of exclusive, attentive, silent listening (Leppert 2002, Riley 2004, Müller 2014).

Throughout the nineteenth century, the music of Beethoven again provided an important new terrain for experimentation (Bonds 2014). A further step came in 1876, with the construction of the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, where audiences were plunged into darkness and forced to face the stage in seats fastened to the floor or in the rare boxes situated behind the rest of the audience. As a whole, Wagner’s theater was conceived to eliminate the social interactions that had been encouraged by horseshoe-shaped Italian opera houses (théâtres à l’italienne), as well as to impose a particular reception of the work in a literally structural gesture—one inspired by the Romantic theories to which Wagner gave decisive form in his ideas on the Gesamtkunstwerk (Brown 2016).

Analysis played an essential role in concert life as well, whether in program notes or separate brochures, to which Leon Botstein first drew musicologists’ attention (Botstein 1992). These textual crutches were written by music writers, passionate amateurs, and often by composers for their own works. They accompanied the music in its technical evolutions during a period when composition by motif and the infinite development of Beethovenian or Wagnerian inspiration became widespread practice. This permanent attention to the sound of music itself called for a new kind of listening on a systematically microscopic level. Thus, disoriented listeners turned to the auditory prosthetics provided by the authors of the works themselves or by specialists in aiding reception of these masterpieces from the repertoire.

One among many potential examples is a several-page note written by Camille Saint-Saëns for the May 19, 1886, premiere of his Third Symphony, commissioned by the Royal Philharmonic Society and premiered at Saint James’s Hall in London (Saint-Saëns 1887a). Illustrated with numerous musical excerpts, Saint-Saëns’s listening guide also followed his score across the English Channel for the Parisian premiere of the symphony at the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire the following January.

The brochure, printed separately by the publisher of the score, opens with an message to French listeners following the London custom of “offering audiences a succinct analysis, exempt of criticism, of works presented in a concert.”15 According to the composer, this practice has an important advantage “from the perspective of musical intelligence.” Saint-Saëns distinguishes his text from the sort of analysis typically practiced by journalists who were intent on issuing judgments, affirming that his is an objective analysis offered to the listener through an account of how the work was composed. Throughout his description of the symphony, Saint-Saëns qualifies the thematic material from an expressive point of view, never using terms of aesthetic value (after an introduction of “a few plaintive bars” “the initial theme, sombre and agitated in character” “leads to a second subject marked by a greater tranquillity”; the theme of the Adagio is “extremely quiet and contemplative” the coda of which is “mystical in sentiment,” etc.).16 The composer’s program note is radically different from a journalist’s review in the sense that it describes the artist’s project rather than seeking to capture an individual listening experience (“The composer has sought, by these means, to avoid … ,” “The author, thinking that …”). In large part, it serves to clarify the successive transformations imposed upon the initial material within the context of a work conceived according to the principles of cyclical development.

Saint-Saëns’s analysis traveled beyond the brochure printed by the publisher, also appearing in the musical review Le Ménestrel a few days before the Paris concerts of January 1887 (Saint-Saëns 1887b). The introduction to this version of the text refers to “a rapid, preventative analysis” destined to allow listeners “to orient themselves more easily within this extremely interesting work” (1887b, 6). As with a Wagner drama, listening to Saint-Saëns’s symphony means recognizing and remembering functional melodic fragments so as not to become lost in the modern music’s oceans of continual development (Thorau 2009).

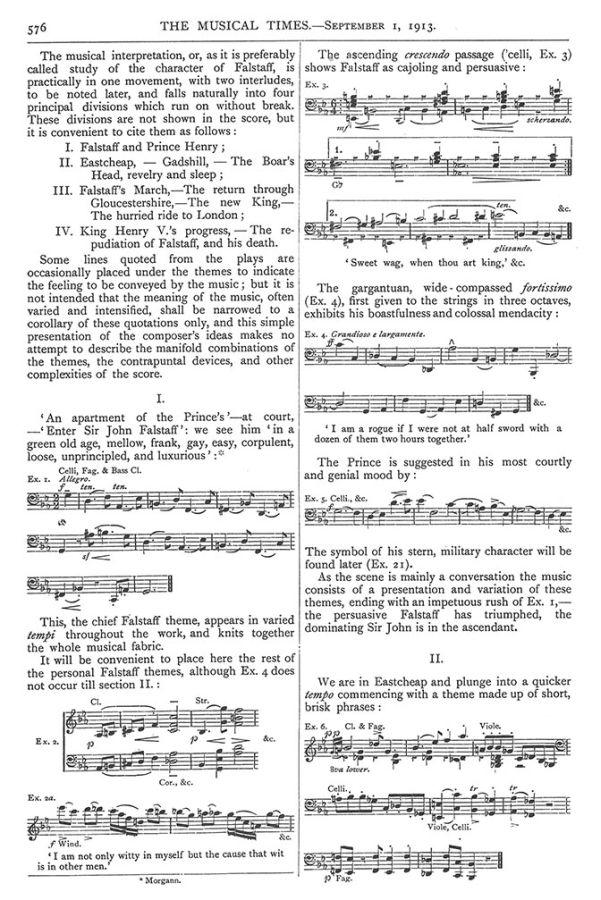

Notes by composers were not limited to premieres, and their pronouncements could wield determining influence years after they had been published, as evidenced in the case of Edward Elgar’s Falstaff, a symphonic study in C minor. In 1913, the composer wrote the article for The Musical Times (Elgar 1913). After outlining the sources for the work and the debate among specialists concerning the character of Shakespeare’s Falstaff, the composer set forth the general concepts of his score and guided the reader through the score, page by page (see figure 3.2). Elgar’s text does not concern itself with the tonal plan or give an explanation of his compositional process, nor does it allude to the orchestration (a third of his musical examples refer only to the main instruments used). Most of the text is given over to a systematic inventory of musical motives as they are heard, in chronological order, and in close coordination with the steps of the narrative program. In other words, Elgar’s article offers a sort of textual reduction of his work that uses a lexicon he deemed accessible to concert audiences. In the end, the article assumed the form of a performance, following the unfolding of the work in a more condensed manner to better guide future listening.

Figure 3.2 Excerpt from the Musical Times, September 1, 1913

Some fifteen years later, in the summer of 1929, a polemic concerning the way in which audiences should listen to the composer’s “symphonic study for orchestra” began, published in the same journal. Each episode in this debate placed the program notes at the heart of its arguments. The debate began with a review of Percy A. Scholes’s The Listener’s History of Music, citing a passage in which Scholes doubted that most listeners are capable of following the rapid sequence of the events and passions represented in Elgar’s Falstaff, even with “the programme book” in hand. Disagreeing with Scholes, the author of the review explained that some of his musician friends who had initially disliked Elgar’s score changed their minds when they learned of the numerous details it contained, concluding “A point-to-point setting doesn’t always call for a point-to-point hearing. Falstaff is gorgeous in sum because of its extraordinary wealth of detail. Our concern is with the sum” (G. H. 1929).

Thereafter, the debate over Falstaff centered on several matters: the classic argument about music’s ability to portray a literary program; more recent theories about the nature of musical listening; and a dispute about the utility of an analysis written by the composer. Scholes replied in The Musical Times, first defending the authors of program notes, who, since 1913, had always written with the authority of the composer. Then, reviewing Elgar’s prose word by word, he showed that if the composer had pointed out so much in his work and then chosen to bring that detail to the public’s attention, then it must be useful to the public (Scholes 1929), finally returning to his theory that Falstaff was “the musical equivalent of a magnificent but much too rapid cinematograph film” (698).

Several readers of The Musical Times responded to Scholes’s article in the following issue, including someone who signed his piece “A Student of Music”:

I suggest that Elgar intends his admirable prose study to be regarded as a commentary on his symphonic study by those who are sufficiently interested to go deeply into the subject, and not as a mere programme note of which the thousandth word should coincide with the last note of the music. (In treating of this, Mr. Scholes makes a little slip: the mendacity theme does not appear in Section 1.) Goodness knows, an analysis which is “at once so copious and so felicitous in its expression that it would be an impertinence on the part of any other writer to attempt an analysis of his own” is needed by a public whose ignorance of and indifference to the world’s greatest dramatist is notorious”. (Musical Times 1929)

This response helps to understand that Elgar’s text was not merely a verbal transfer of the score but also a veritable hermeneutical aid (as proved by its mention of the emerging interpretive conflict embodied in the reference to the “mendacity theme”). It also raises (again) the question of the appropriate scale for listening to Falstaff, pointing out the limited capacities of the average listener in a concert setting. The modern work seems to surpass the moment of performance because the density of its motivic and formal content is such that the amateur must devote hours of preparation to its untangling. The listener also must seek out and hear the score as many times as possible in order to align his aural sensations with its content. Coming to know a work had become a time-consuming labor that involved memorization of the text and its incorporation, in the literal sense of the term—an activity later somewhat facilitated by radio and high-fidelity recordings.

The chain of glosses on Falstaff has continued over the years. In 1932, the amateur Robert Lorenz published a study that benefited from “the original commentary the composer wrote for The Musical Times in 1913, which is not only a model of lucidity but a distinguished example of English prose” (Lorenz 1932). More recently, J. P. E. Harper-Scott created a “Table of Motives” based on Elgar’s text (Harper-Scott 2005).

The Rise of Musical Literacy

If Elgar’s gloss remains inseparable from his work, it is not only because composers have continued to present themselves as supreme authorities in the musical world but also because our use analytical texts has changed very little.17 During the entire twentieth century, identifying the order in which motifs appear, naming them, and describing their place in the harmonic and formal development of a work—in short, the entire apparatus of a cursory reading-listening—remained meaningful to most concert-goers and record-lovers. During a time when scholarly analysis became increasingly legitimate, this form of analysis for the ear prospered; although simpler from a technical point of view, it proved incredibly effective in intensifying the aesthetic pleasure of the listener.

Analyses for general audiences profited from a favorable economic and social context. Greater development of amateur instrumental and vocal activities was encouraged with a decline in the cost of instruments and scores, thanks to their increasingly efficient production. Wider populations adopted the social practices of the aristocratic classes, whose education and social life had always reserved an important place for the arts. Even as early as the first third of the nineteenth century saw the number of private teachers explode, while public education in the schools and conservatories was becoming accessible to tens of thousands of children across Europe. At the same time, musical institutions such as choral societies, brass bands, and symphonic associations multiplied and were playing an important role in the education of battalions of music amateurs.

In due course, artistic policy responded to this expanding musical economy made possible by the spread of musical literacy and, more specifically, by a desire for personal liberty that captured the spirit of the previous century’s Enlightenment ideology and intellectual life.18 This individual emancipation was not without certain ambiguities, however; although many insisted on the ability of musical practice to improve one’s condition (and to become better integrated in an egalitarian society), others imagined that music might be used to serve the goals of political conservatism. Indeed, during the first half of the nineteenth century, powerful philanthropic movements undertook projects to use music as a means of moral control and of maintaining social order. Europe was filled with orchestras and choirs composed of amateurs who were encouraged and funded by aristocratic or bourgeois elites (Gumplovicz 2001, Menninger 2004, McGuire 2009). After that first step of placing an emphasis on basic musical instruction (learning to read music and the rudiments of instrumental or vocal technique) came the time for a deeper intellectual education.

The United Kingdom was a sort of laboratory for such a socio-artistic project involving the development of musical appreciation (Rainbow 1984, Tyrrell 2012). Although the genre that dominated the field until the 1850s and 1860s was the program note, as Catherine Dale has shown, this was not a homogenized corpus of texts (Dale 2003, 36). Program notes included articles published in the press before concerts (for example, in The Harmonicum, The Musical World, or The Musical Times) but also separate sheets offered as programs on the day of the concert or in brochures sold at the door of the main concert halls, not to mention the texts sold in bookstores. These analyses were as often purely textual, as they were enriched with musical examples, or they were topics of public lectures. This considerable variety in presentation was the result of an exponentially increasing demand that was being satisfied by individual musical institutions, without particular concern for presenting a unified, emerging field of knowledge.

English proponents of musical analysis invested in public and private schools in order to reach future musicians at as early an age as possible. One of the primary figures to write on the subject was John Stainer (1840–1901), with the title of “Inspector of Music in the Training Colleges and Elementary Schools of the Kingdom”; he noted, “Our real want in England at this moment is not professional performers or even composers, but intelligent hearers” (Stainer 1892, 57). His assistant, William Gray McNaught (1849–1918), also held that the purpose of schools was not to produce composers and performers but to issue “armies of trained listeners.”19

The American term music appreciation was imported to England at the beginning of the twentieth century.20 Beginning as far back as 1908, Mary Agnes Langdale, who deplored the fact that children’s education focused merely on the gymnastic education of their fingers, wrote that “we are not training them to become intelligent listeners, or enabling them to make in their afterlife any extended acquaintance with that great literature of music which should be open to all” (Langdale 1908, 202). According to Langdale, the ideal content of an education in music appreciation included the following:

The laws of musical form or design, of harmonic colouring, the outlines of musical history and development—these things are just as vitally necessary for the rational enjoyment of music as are the perception of line and form and colour for the appreciation of a great picture. (Langdale 1908, 203)

The recommended repertoire included works by Corelli, Haydn, Mozart, and Purcell, as well as recent modern works some of which came from the Russian, French, or Scandinavian schools. For the most advanced students, Dale recommended classes in analytical harmony and formal approaches, completed with the requirement of attending concerts of chamber music.

This cause was taken up, in turn, by Steward MacPherson, professor of harmony and counterpoint at the Royal Academy of Music in London, who wrote Aural Culture based upon Musical Appreciation (editions in 1912, 1913, 1918) with his closest disciple, Ernest Read. MacPherson’s work as an activist teacher brought him to create special courses for the Streatham Hill High School for Girls, in 1908. His program prioritized the intellectualization of the listener’s relationship with music: “to stimulate the hearing sense, and to cultivate the power of taking in music intellectually instead of as a mere “general impression,” largely the result of physical sensation” (MacPherson 1908, 11).

In concert societies, in the press, and in English schools (although the observation holds for other countries as well), there was an ever-increasing enthusiasm for listening guides, whether printed or orally transmitted. Composers, music-writers, pedagogues, and amateur musicians were all called upon to contribute to the genre (yet another explanation for the varied nature of approaches described here). Every concert had its program note, hardly an issue of a journal was printed without including an analysis of a work, and few were the classes on music that did not seek to educate the ear on the history of musical languages and forms.

The grammar of listening that was spread during this period grew from the basic concepts of musical notation (“principes de musique”) that were often printed at the beginning of instrumental or vocal manuals and treatises, up until the middle of the nineteenth century. Then, the rules of solfège were replaced with the precepts of analytical reading, with basic harmonic principles or with biographical and historic knowledge. In the space of a century, an educational culture was set into place—one shared by thousands of children and adults. Thanks to the action of activists in aural education, this common knowledge surpassed the distinctions of social class. The literature accompanying musical activity had become as universal as the works it analyzed.

In the Composer’s Workshop

The Romantic aesthetic and the avant-garde discourses of the twentieth century have accustomed us to considering the artists’ words as of capital importance for understanding the meaning of their works. This situation seems further confirmed by other indicators. For example, until only recently, little notice was given in the musical world to the performer’s or listener’s point of view. Indeed, I have purposefully saved my consideration of composers’ analyses for the final section of this chapter.

Artists’ writings—be they as voluminous as those of Richard Wagner or as slight as those of certain painters and architects—have long eclipsed activities behind the scenes for producing the auctorial word. Musicologists have only recently taken interest in the content of the composition classes that many composers gave during their lives.

In Conservatoire curricula, the titles given to composition classes do not always reveal the fact that analysis occupied an important part of their instruction. That the transmission of compositional craft is largely an oral process further complicates the historian’s task, making it necessary to reconstruct teaching practices using indirect evidence and recollection. Finally, in published treatises, it is often difficult to distinguish between content corresponding to teaching practices and theoretical constructions invented after the fact. With a few precautions, it is nevertheless possible to recreate, often only fragmentarily so, the analytical tools used in classes of musical composition (classes d’écriture).

The most frequent activity involves reading and commenting upon worthy examples. The teacher, seated at the piano with his students and with the score open on the stand, takes apart the mechanism of the work. More generally, it is the sort of reading that had long been practiced in the rhetoric classes of the lycées, where a craft was learned by contact with classic texts, according to the principle of imitating the ancients. In the nineteenth century, the libraries founded in the early days of Europe’s principal music schools played a primordial role, serving as near-inexhaustible reservoirs of commendable models. During the first half of the nineteenth century, those responsible for the continent’s principal public collections (such as Siegfried Dehn at the Königlischen Bibliothek in Berlin, or Gaetano Gaspari at the Liceo musicale of Bologna) spent considerable sums of money to create libraries of musical literature that were as complete as possible. Works of early music were placed alongside the latest scores, transforming these music libraries into gigantic depots of ideal forms—the musical equivalents of plaster copies of antique and Renaissance statues in schools of fine art or anthologies of the best works of literature, published and distributed in schools.

At the Paris Conservatoire, professors regularly found their teaching materials in the music kept in the institution’s library. Léo Delibes, head of a composition class from 1881 to 1891, regularly visited the Conservatoire library to borrow scores by Richard Wagner, using them as examples in his classes (Pougin 1911, 271). For the entire nineteenth century, analysis was inseparable from an artisanal vision of the composer’s craft, in which the rules of the trade were transmitted by example—or in other words, through the analysis of tried-and-true solutions found in earlier works. This practice began to evolve at the beginning of the twentieth century, however. Without abandoning the modes of transmission inherited from the ancien régime, more and more composers gave an increasingly important place to the role of analysis in their lessons.

Two figures embody the didactic model that was gradually imposed in twentieth-century Europe: Vincent d’Indy and Arnold Schoenberg. In France, d’Indy transformed the Schola Cantorum (founded in 1894) into a school rivaling the Paris Conservatoire, one characterized by the fact that it was organized around composition classes led by d’Indy himself (Campos 2013). The essential part of d’Indy’s teaching, apart from the time devoted to correction of student works, involved analysis at the piano of the more or less celebrated works of an immense music history. This was presented to show the progressive emergence of modern compositional tools or, more exactly, the tools useful for the affirmation of d’Indy’s Wagnerian-Franckian aesthetic (a synthesis of Gregorian rhythms, tonal theory, motivic development, and so forth). This educational structure, captured in the form of a treatise published in several volumes and compiled with the assistance of d’Indy’s faithful pupil, served as a model for classes of teachers as different as René Leibowitz and Olivier Messiaen some fifty years later (Campos 2009).

During those same years, first in Vienna and then in Berlin, Arnold Schoenberg gathered a group of students that included Anton Webern, Egon Wellesz, Erwin Stein, Heinrich Jalowetz, and Alban Berg (Johnson 2010, 5). The principles behind his teaching became public knowledge with the publication of his Harmonielehre in 1911, although the volume did not have the intension of divulging its author’s teaching techniques; rather, it was to present his theoretical positions (Schoenberg 1911). To best grasp Schoenberg’s oral pedagogy, one must turn to the recollections of his former students. Notes taken in Schoenberg’s classes by Alban Berg, for example, show that the order of subjects and exercises listed in Schoenberg’s treatise of 1911 correspond to the order of the lessons Berg received as a young musician (Calico 2010). In the memoirs of Egon Wellesz, one learns that Schoenberg “makes his pupils analyse [the works of the great masters, from Bach to Brahms]. He also urges his pupils to examine their own compositions and discover for themselves wherein lies any fault or clumsiness; he then points out better solutions—not one, but many—in order to show them clearly the abundant possibilities of realisation.”21

Like d’Indy, Schoenberg’s teaching principles viewed works of the past not as cadavers destined for dissection but, rather, as living things that could nourish the analyst’s own creative activity. This conception of the past as a resource explains why both of these composer-teachers did not hesitate to apply anachronistic ideas to works from the past. In the case of Schoenberg, this included notions of Grundgestalt (defining a motive according to both morphological and functional criteria) and of developing variation (Dudeque 2005, 174). Just as Schoenberg’s own theories of music during this period were very much a synthesis of ideas borrowed from his predecessors—in particular from the thinking of A. B. Marx on musical form (Die Lehre von der musikalischen Komposition, 1837–1847) and that of Simon Sechter on harmony (Die Grundsätze der musikalischen Komposition, 1853–1854)—his analytical technique was not entirely self-invented (Wason 1985, Krämer 1993, Krämer 1996). In large part, it drew upon the traditional practice of collective reading of classics under a master’s supervision.22

Schoenberg’s real innovation was to extend the benefit of his commentaries to a public much larger than the circle of apprentice composers assembled in his studio. Further, these apprentices later became disciples who participated in a broad diffusion of Schoenbergian analytical methods. The same was true in Paris, where Vincent d’Indy’s students Albert Groz, Georges Loth, and August Sérieyx published analyses of new works composed by musicians with ties to the Schola Cantorum. Perhaps the best-known example in this domain is Alban Berg’s guide to Schoenberg’s recently completed Gurrelieder (Berg 1913). In his guide, Berg applies the rules of descriptive analysis (motivic dissection, harmonic divisions, orchestration techniques) as he learned them from his master:

I have tried to speak with cool objectivity about the different things in the music as they appear: in one place about harmonic structure (as in the discussion of the Prelude), in other places about the construction of motives, themes, melodies, and transitions; about form and synthesis of large musical structures, about contrapuntal combinations, choral writing, voice leading, and finally about the nature of the instrumentation. (Berg 2014, 11)

Berg’s analysis is based on 129 musical examples, which for the most part are orchestral reductions on two staves. To sort out the complicated polyphony, many are even noted on three staves and with up to three voices per staff. The analytical work is therefore in constant tension between schematic reduction with an eye to simplifying discursive proliferation and the restitution of the greatest amount of information possible in the name of preserving Schoenberg’s characteristic abundance. Berg’s analysis consists of the most literal description of the score imaginable, focusing on the distribution of motives within the orchestra and the course of their evolution in the time of the work’s performance.

Berg published three other thematic analyses of his teacher’s works (one devoted to the Kammersymphonie, opus 9, and two others to Pelleas und Melisande, the second an abridged version of the first) (Berg 1993). And Schoenberg himself wrote a lot of analyses of his own works (Krones 2011). These analyses are inextricably linked to the new concert practices mentioned earlier, as well as reflecting the aesthetic debates of the period, as they no longer separate the performed composition from the analysis that sheds light on its form. These analyses helped composers consolidate their musical control by publicly displaying the demiurgical capacity for rationalizing their own production and imposing the keys to its interpretation. Igor Stravinsky’s provocative declarations of the 1930s on the virtue of the phonographic recording as the sole means of permanently capturing his artistic will (at the risk of reducing musicians to reading automatons) are well known examples of this phenomenon (Stuart 1991).

Thus, long before the prescriptive use of the recording emerged in the second half of the twentieth century, the most advanced composers had already set into place effective means of control through analytical verbalization. This exercise of control ultimately had important consequences on compositional methods themselves: as composers anticipated needing to justify their creative process or aesthetic intentions, they began to increasingly document their work as they composed (it became more and more common for composers to save their drafts and sketches)—sometimes using what were once the products of analysis, such as motivic tables or harmonic schemas, as compositional tools in their own right (Campos and Donin 2005, Donin 2012). Today, musicologists continue to debate the meaning of the motives that Richard Strauss wrote in the autograph scores of his symphonic poems, or the function of the annotations in the librettos of his operas, the margins of which often include musical motives, melodic lines, rhythmic ideas, or indications of key areas.23 Were these notes used in the course of compositional activity? Or were they anticipations of the sort of information that would need to figure into future listener guides?

The analytical activity of the most inventive composers at the start of the twentieth century was forged at the intersections of several situations, of several interwoven projects. It is at once the exemplification of theoretical framework, a pedagogical tool, a means of communicating with and justifying work to general audiences, and an instrument of composition. This elastic usage of analysis would continue through the twentieth century, encouraged by new conceptions of the composer’s social function. Carried along by a wave of intellectualization that swept the artistic professions, the modern creator was increasingly expected to demonstrate his or her capacity for mastery in a variety of domains, from conducting to public speaking, not to mention having institutional knowledge, doing pedagogical work, and applying analytical capacities.24

The ability to empirically dismantle musical scores is part of a longstanding artisanal tradition, in which analysis is a logical tool to unpack models and to imitate great masters. The sole recent innovation in analysis, beyond the evolution of the musical languages in question, is its abandonment of closed circles of specialists and its adoption of larger public arenas in which the analyst competitively proposes ideas to colleague-competitors and, especially, to audiences that must be persuaded to choose one side or another. In the final episode of hermeneutic conversion, those who claim to hold musical authority are expected to compose both the works and the minds of their listeners.