chapter 5

Travel Writing

Just as opportunities for travel expanded greatly in the nineteenth century, given the increased mobility owing to advancements in transport by train or steamship, combined with rising incomes and the promotion of organized travel by figures such as Thomas Cook (Schivelbusch 1986, Fox 2003, Brendon 1991, Withey 1997), so a plethora of travel literature was created. This took different forms—guidebooks by Baedeker and John Murray, poetry, novels, and essays, but also writings descriptive of travel—all representative, as Kenneth Churchill suggests, of a “thick new layer of literary associations” (Churchill 1980, 64). The contributions that such publications made to the intellectual culture of the nineteenth century were manifold—whether in terms of knowledge exchange, geography, ethnography, cultural identity, philosophy, aesthetics, or historical and political commentary; these texts also offered a range of narrative strategies in documenting the personal travel experience and its relationship with wider notions of authority and authenticity. As nineteenth-century travel developed, so too did a perceived tension between “tourist” and “traveler”; while the former, representative of “the cautious pampered unit of a leisure industry,” was often seen as “a dupe of fashion, following blindly where authentic travelers have gone with open eyes and free spirits,” the latter could display “independence and originality … boldness and gritty endurance under all conditions” (Buzard 1993, 1–2). Not only does this debate resurface in contemporary scholarship on travel (O’Reilly 2005; Lisle 2006, 77–83), but the continued interest in the value of travel literature more generally underscores its cultural significance for modern readers (Hall and Tucker 2004, Pratt 2008, Azariah 2017).

This chapter focuses on writings descriptive of travel from 1800 to 1914; these texts were penned by some of the most significant writers of the age—Goethe and Heine in Germany; Dickens, Gissing, Thackeray, and Kipling in Britain; Flaubert, Nerval, Stendhal, and Gautier in France; and Henry James in America—supplemented by those specializing in the travel experience, along with an increasing number of female literary travelers that included Mary Shelley, Janet Ross, Frances Trollope, Mary Kingsley, and Vernon Lee. The close relationship between some of these texts (Block 2006); the strong presence of musical documentation, discussion, and allusion; and the influence of music on writing style confirm a network of musical discourse suggestive of the significant status of music within nineteenth-century intellectual culture.

Strategies in Documenting Musical Otherness

Ideas of “restless movement, wandering, pilgrimages, quests, and other journeys” in literary form, as C. W. Thompson suggests, are “intimately bound up with Romanticism,” whether motivated by “flights from social and psychological entrapment; expansions of the self driven by desires for change and heroic adventure; or quests for origins, energies, and imaginative riches” (Thompson 2012, 1). One of the primary drivers of nineteenth-century travel literature—in the spirit of the earlier scientific travelers—was to document aspects of otherness, and descriptions of musical practices provide a rich source of information for the musicologist and social historian. Overt examples include comparative listings of singers’ salaries (Inglis 1831a, 2:383); and the costs of attending opera, such as the eighty sequins for a box and thirty-six centimes for a pit seat for regular subscribers at La Scala, noted by Stendhal in 1817 (Stendhal 1959, 22, 24). Others described performance events in fine detail, such as the febrile atmosphere at the second performance of Lohengrin in Paris in 1891:

The French are still bitterly hostile to the Germans, and the Boulangists … determined on a great demonstration against having this German piece given at the Opera. … The audience received the opera not only kindly but enthusiastically, applauding and bravoing every good part. At the end of the first act every one hurried to the foyer and the balconies in front to see the crowd outside. … The open place in front was occupied by a large hollow square of gens d’armes [sic] and behind was a surging mass of men. Every few minutes the police would arrest two or three of them and march them off. In the house when before the second act the stage manager announced that the heavy villain of the opera had a bad cold and that the audience must bear with him, some man downstairs proposed that we sing the Marseillaise hymn so as to help out, and immediately the whole audience rose to their feet and went wild with bravos and hisses. The man was arrested and taken out, and no Marseillaise was sung. (Hamilton 1893, 242–243)

Writers also remind us of the music-making of the travelers themselves—whether the whistling “German commis-voyageur, with a guitar” on Thackeray’s journey from Smyrna to Constantinople (Thackeray 1846, 95); the “sublimely hideous” combination of accordion, violin, and key-bugle described by Dickens on his voyage home from America (Dickens 1842, 2:230); or Nelly Bly’s citing of the superior performing skills of the “second-class passengers” including a poignant rendition of “Who’ll Buy My Silver Earrings?” by a girl with a “sweet, pathetic voice” (Bly 1890, n.p.)—all contributing to a sense of the nineteenth-century soundscape.

More significant than simple documentation, however, is the way in which music is treated in travel writings, which highlights not only some of the central issues in discourses of travel but also some specific literary devices and strategies. To distinguish themselves as “travelers” rather than “tourists,” travel writers needed to confirm their status as a “proper performer of cultural gestures” (Buzard 1993, 97). While a certain cultural accreditation could be established through discussion of familiar tourist sights and artifacts, avoidance of the “beaten track,” combined with a suggestion of a more insightful response to culture—sometimes in the form of insider knowledge—created a more authoritative travel narrative. Hence, writers were keen to highlight their personal connections to composers—whether Goethe’s description of his creative relationship with Philipp Christoph Kayser (1755–1823) (Goethe 1970, 415–420), Heine’s recollecting a performance by “the wondrous boy, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy” in his Reisebilder (Heine 1904, 103), or Mary Shelley’s confirmation that Henry Hugo Pierson (1815–1873) found creative inspiration in the German countryside and was a particular admirer of Les Huguenots (Shelley 1844, 1:233, 248); similarly, James Galiffe’s extended account of a meeting with Rossini noted that the composer’s conversation was “that of a gentleman—with a tint of levity and epicureanism which by no means misbecomes him” and established his preference for Otello and Elizabeth as opposed to the “trifles” Tancredi and L’Italiani in Algeri (Galiffe 1820, 1:219–223). Writers could also affirm their cultural superiority by offering judgments on specific composers and their works; Stendhal, for example, proclaimed his advocacy of the music of Haydn and Cimarosa (representative, respectively, of “harmony, with its transcendent beauty” and “melody with its enchantment of delight”), and “the bright hope of the Italian school, Rossini” (Stendhal 1959, 12, 347).1 If the value of the opera La Testa di Bronzo by Carlo Soliva (1792–1853) proved more difficult to assess, as its “perpetual reminiscence of Mozart” suggested either “a brilliant pastiche” or “a work of genius” (9–10), Paolo e Virginia by Pietro Carlo Guglielmi (1772–1817) created no such dilemmas:

Overture: complex, elaborate stuff, thirty or forty different themes in discordant juxtaposition, all too cramped for the listening ear to grasp, too crowded to awaken the slumbering sensibilities; an arduous, arid and wearisome piece of work, leaving the mind already surfeited with notes before the curtain rises. (Stendhal 1959, 351)

Elsewhere, Goethe revealed his penchant for the vocal music of Morales, Marcello, Palestrina, and his “favorite composer,” Cimarosa (Goethe 1970, 369), Charlotte Eaton responded to Allegri’s Miserere as representative of “music of another state of being” (Eaton 1820, 3:136), and Vernon Lee described the “solemn tenderness” of Ein deutsches Requiem in Meiningen prior to the unveiling of the Brahms monument in 1897 (Lee 1908, 62–68). References to a catalogue of performers offered writers the opportunity to display their musical taste, including the “excellent violinist” Johann Friedrich Kranz (1752–1810) highlighted by Goethe, or Stendhal’s emphasis on the “pure vocal quality” of Angelica Catalani (1780–1849)—despite her lack of stylistic variety (Goethe 1970, 369; Stendhal 1959, 25–26). This led inevitably to discussions of performers’ relative merits; for Stendhal, the “noblest bass voice” of Fillipo Galli (1753–1853)—praised also for his acting skills—was preferable to the “mechanical instrument” of Renier Remorini (Stendhal 1959, 6, 16); Inglis posited the superiority of the soprano Adelaide Tosi (1800–1859) to Catalani in terms of her “sweetness and melody of tone” (Inglis 1831a, 1:108), while Mary Shelley suggested a clear preference for Luigi Lablache (1794–1858) over Ignazio Marini (1811–1873) (Shelley 1844, 1:107). The authority of these cultural pronouncements was heightened by the authors actually being on the spot; as Goethe noted, echoing Kayser’s views on Morales, “it is only here [the Sistine Chapel] that one can hear and should hear this type of music” (Goethe 1970, 478).

As the primary function of travel writing was to “[acclaim] the foreign as gratifyingly dissimilar from the familiar” (Chard 1999, 4), descriptions of music—along with landscape, local custom, food, and speech—proved particularly effective for this purpose. Cataloguing of “strange” musical instruments, for example, was particularly prominent in African travels, whether Mary Kingsley’s discussion of the Bubi tribe (whose music-making involved the elibo—a wooden bell with clappers, the percussive shaking of bullock-hide, and an instrument “never seen in an identical form on the mainland … made like a bow, with a tense string of fibre,” one end being “placed against the mouth, and the string is then struck by the right hand with a small round stick, while with the left it is scraped with a piece of shell or a knife-blade”) (Kingsley 1897, 66–67), or various forms of marimba detailed by Verney Cameron in Manyuéma, M. A. Pringle in Inhambane, and James Grant in Uganda (Cameron 1877, 248; Pringle 1886, 69–70; Grant 1864, 225).2 Closer to home, Janet Ross’s account of the soundscape of the Italian town of Leucaspide included the “cupa-cupa”:

a large earthenware tube, with a piece of sheepskin stretched tight over the top, and a stick forced through a hole in the centre. The player begins by spitting two or three times into his hand, and then moves the stick up and down as fast as he can; this makes an odd, droning sound, rather like a bagpipe in the far distance.

(Ross 1889, 154)

Even more prevalent were descriptions of a distinctive vocality as part of a vernacular musical otherness. Goethe offered a detailed discussion of Venetian gondoliers’ music, where “verses by Ariosto and Tosto” were chanted “to their own melodies”:

The two singers, one in the prow, the other in the stern, began chanting verse after verse in turns. The melody, which we know from Rousseau, is something between chorale and recitative. It always moves at the same tempo without any definite beat. The modulation is of the same character; the singers change pitch according to the content of the verse in a kind of declamation. … The singer sits on the shore of an island, on the bank of a canal or in a gondola, and sings at the top of his voice. … Far away another singer hears it. He knows the melody and the words and answers with the next verse. The first singer answers again, and so on. … The sound of their voices far away was extraordinary, a lament without sadness, and I was moved to tears.

(Goethe 1970, 92)

Combined with the “penetrating tones” of the women sitting on the seashore, singing similar melodies to which “their men reply” (Goethe 1970, 93), as Rodney Stenning Edgecombe notes, this description contributes to an evolutionary stemma for the barcarolle genre (Edgecombe 2001, 253–254). Two striking tropes often combined in these descriptions of a vernacular musical otherness are those of monotony and melancholy. Examples include Flaubert’s description of the singing of a cabin boy in Par les champs et par les grèves—a “slow, monotonous lay … repeated again and again” which “swept softly and sadly over the ocean, as some confused memory sweeps through one’s mind”; Inglis’s references to the “melancholy cast” of the “mountain airs” of Norway or a Spanish muleteer singing “a remarkably beautiful, but somewhat monotonous air”; or Lafcadio Hearn’s description of Mionoseki boatmen in Japan “intoning in every pause a strange refrain of which the soft melancholy calls back to me certain old Spanish Creole melodies heard in West Indian waters” (Flaubert 1904, 51; Inglis 1829, 64; Inglis 1831a, 1:17; Hearn 1894, 1:237). Similarly, the vocalizing over a street organ that George Gissing heard in Cotrone consisted of “rising tremolos, and cadences that swept upon a wail of passion; high falsetto notes, and deep tum-tum of infinite melancholy” (Gissing 1901, 95). Gissing’s adjective—“infinite”—borders on hyperbole, another common literary technique used to highlight the “otherness” of a foreign object by “acclaiming [it] as dramatic, striking and remarkable” (Chard 1999, 4); Eaton’s description of a performance of Allegri’s Miserere as containing “a deeper, more pathetic sound than mortal voices ever breathed … more wonderful … than any thing I could have conceived,” is just one of the plethora of examples of this device (Eaton 1820, 3:136–137).

As Nigel Leask reminds us, as part of a “curiosity” at the heart of travel writing there is a tension between a “socially exclusive desire to possess the ‘singular’ object” and “an inclination to knowledge which will lead the observer to a rational, philosophical articulation of foreign singularities” (Leask 2002, 4). This is particularly prescient in Western travelers’ portrayal of the East where, as Helen Carr suggests, the balance between a “complicity with imperialism” and the “anxieties, uncertainties … the profound doubts about the continuation of Western progress, indeed doubts about the possibility of progress at all” is often fragile (Carr 2002, 73). Descriptions of music often reflect these tensions. Bennett Zon, focusing on texts such as Edward Lane’s An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (1836), has highlighted how the “overarching concept of simplicity” (often conflated with animality, and the language of violence, passion, and excess) is frequently used as a “trope for degeneration” in representations of music in Orientalist travel literature (Zon 2007, 212). Hence, while children are able to learn Egyptian music “very easily and early,” and “most of the popular airs of the Egyptians … are very simple,” Lane also suggested how, being “excessively fond of music,” the Egyptians were “generally enraptured with the performances of their vocal and instrumental musicians,” regarding musical study “as exercising too powerful an effect upon the passions, and leading a man into gaiety and dissipation and vice” (Lane 1836, 2:59–61). Other writers dismissed “native” music through suggestions of unpleasant and overly dissonant noise. Charles Doughty’s characterization of Bedouin singers in Travels in Arabia Deserta cited a “nasal braying” that created “a hideous desolation to our ears,” accompanied by “stern and horrid sounds” from the one-stringed rabeyby (Doughty 1888, 1:263); if the bagpipe and “scraping fiddle” in Cairo was “extremely irritating to the nerves” of Gérard de Nerval (Nerval 1929, 1:5), John Carr was disturbed by the “screaming sounds … from the strained throats” of Russian sailors (Carr 1805, 360), while Nelly Bly noted a “strange, weird din” of “dire confusion and discord” at a Singapore funeral, and the “alarming din upon samisens, drums and gongs” that accompanied the “unbearable” nasal singing of geisha girls in Japan (Bly 1890, n.p.). Despite Isabella Bird’s attempts to attain a critical balance in Unbeaten Tracks in Japan (“in many things … the Japanese are greatly our superiors, but … in many others they are immeasurably behind us”), she was dismissive of music-making in Tochigi; “kotos and samisens screeched and twanged,” songs included “jerking discords” that were “most laughable,” the Shinto festivals consisted of “dissonant squeaks and discords,” and evening music-making included “an agonising performance, which they call singing … which sounds like the very essence of heathenishness” (Bird 1880, 1:352, 97, 134–135). For the American writer Lafcadio Hearn, however, Japan represented a “romance” forcing him “to doubt whether the course of our boasted Western progress is really in the direction of moral development”; reveling in the Japanese musical soundscape, his “other” is, in contrast, something to be celebrated:

It is strangely difficult to memorize the melody of a Japanese popular song, or the movements of a Japanese dance; for the song and the dance have been evolved through an aesthetic sense of rhythm in sound and in motion as different from the corresponding Occidental sense as English is different from Chinese. We have no ancestral sympathies with these exotic rhythms, no inherited aptitudes for their instant comprehension, no racial impulses whatever in harmony with them. But when they have become familiar through study, after a long residence in the Orient, how nervously fascinant the oscillation of the dance, and the singular swing of the song!

(Hearn 1894, 1:272–273)

In terms of African travel, as Tim Youngs concludes, any “humanitarian postures” in Henry Stanley’s travelogue In Darkest Africa are often undercut by his “reinforc[ing] western superiority” (Youngs 1994, 106). Musically, Stanley provides a positive account of the Wanyamwezi tribe, and highlights the excitement of the drummers of the Bandussuma phalanx dance: “accomplished performers, keeping admirable time, and emitting a perfect volume of sound which must have been heard far away for miles,” with “accuracy of cadence of voice and roar of drum” (Stanley 1890, 1:436–437). However, this musical expertise is undercut by Stanley’s negative generalizations elsewhere, reducing the sound world to “minor dances and songs” that are “either dreadfully melancholiac [sic] or stupidly barbarous,” or “more subdued, a crude bardic, with something of the whine of the Orient” (Stanley 1890, 1:436). It was left to other writers to promote the more positive qualities of African music; Mary Kingsley, aiming to offer “an honest account,” described the “elaborate tunes in a minor key” of the boat songs of the M’pongwe and Igalwa tribes (Kingsley 1897, viii, 180), while James Grant documented a seven- or eight-string “nanga” in Karague whose tunings of a “perfect scale” and “full harmonious chord” suggested “that the people are capable of cultivation” (Grant 1864, 183).

The same tensions are evident in writings with a colonial bias. Given music’s clear role as a marker of culture, the lack of musical activity highlighted in Frances Trollope’s trip to America in the 1830s is pointed; describing “dull” evening parties where there was “very little music, and that little lamentably bad,” she claimed: “I scarcely ever heard a white American, male or female, go through an air without being out of tune before the end of it; nor did I ever meet any trace of science in the singing I heard in society” (Trollope 1832, 2:132–133). The emigrant Susanna Moodie suggested that while Canadian women possessed “an excellent general taste for music,” it was “seldom in their power to bestow upon its study the time which is required to make a really good musician” (Moodie 1852, 1:222); and Dickens was critical of the lack of street music entertainment in New York:

But how quiet the streets are! Are there no itinerant bands; no wind or stringed instruments? No, not one. By day, are there no Punches, Fantoccini, Dancing-dogs, Jugglers, Conjurers, Orchestrinas, or even Barrel-organs? No, not one. Yes, I remember one. One barrel-organ and a dancing-monkey—sportive by nature, but fast fading into a dull, lumpish monkey, of the Utilitarian school. (Dickens 1842, 1:209)

This lack of musicality extended to American audience behavior, where the spitting involved in chewing tobacco led Trollope to exclaim: “If their theatres had the orchestra of the Feydeau, and a choir of angels to boot, I could find but little pleasure, so long as they were followed by this running accompaniment of thorough base” (Trollope 1832, 2:195). Related to some of these descriptions were perceptions of progress, or lack of it, and just as Chard has highlighted how in travel literature “the past is always poised to resurge disquietingly within the contemporary topography”—often through the destabilizing presence of the ruin (Chard 1999, 140), so authors frequently reflected upon the loss of an idealized musical past. In his Irish Sketchbook, for example, Thackeray invoked a former time when singing was common in the home, whereas now it was rare for the head of the house to “strike up a good old family song” (Thackeray 1857, 66). Other writers extended this idea by associating music with memory itself; while the familiar tune of a Romantic song led Henry Holland to being “carried back … to the shores of the Faxé-Fiord in Iceland” where he had “unexpectedly caught the sounds of this very air, played on the chords of the Icelandic langspiel” (Holland 1815, 323), Heine typically offered a more poetic example of music’s association with the vanished world of youth:

And then the rosy-cheeked boys will … place the old harp in my trembling hand, and say, laughing, “Thou indolent gray-headed old man, sing us again songs of the dreams of thy youth.”

Then I will grasp the harp and my old joys and sorrows will awake, tears will again gleam on my pale cheeks. … I will see once more the blue flood and the marble palaces and the lovely faces of ladies and young girls—and I will sing a song of the flowers of Brenta. (Heine 1904, 128)

As travel narratives represent a “textual, physical, and cultural space for an exploration and affirmation or reconstitution of identity” (Youngs 1994, 3), it is not surprising that one of the main issues in European travel literature was that of competing levels of national musicianship. For Edmund Spencer, the high-level discussions of music in Austrian periodicals were particularly striking (“if the Austrians were as well informed on every other subject as they are on music, they would be the most intellectual people in Europe”) (Spencer 1836, 157–158), while Thomas Hodgskin, along with many nineteenth-century travel writers, underlined the importance of music to the German psyche:

From knowing the great partiality of the Germans to music, and how extensively it is cultivated by them, I was not surprised to hear this ragged lad talk of music-clubs in villages, nor to hear him regret that he was no longer able to frequent them. Music is to the Germans what moral and political reasoning is to us;—the great thing to which all the talents of the people are directed; and it is as natural that Handel, and Haydn, and Mozart, and Beethoven, the greatest of modern composers, should have been Germans, as that Hume, and Smith, and Paley, and Bentham, and Malthus, the greatest reasoners and political writers of the age, should have been Britons. (Hodgskin 1820, 1:40)

In promulgating other national stereotypes, William Dean Howells’s travels in Britain highlighted “the singing of the angel-voiced choir-boys” in Exeter Cathedral and the vocal prowess of Welsh miners in Malvern: “I asked myself if such heavenly sounds could issue, at this remove, from the bowels of the Welsh mountains, what must be the cherubinic choiring from their tops!” (Howells 1906, 31, 246).

An overview of the various travel writings by the indefatigable Henry Inglis reveals a range of opinions on standards of national music-making. Inglis posits a general lack of musical ability in the ladies of Norway (“some of them possess a little knowledge of music; but a few waltzes, imperfectly played, generally exhaust it”); dismisses “monotonous” and badly executed Swiss airs in Zurich; observes “no symptom of musical taste, either in public performances, or amongst the people generally” in the Tyrol; suggests a lack of musical encouragement in Jersey; and concludes that the “national vanity of the French” is the only explanation for their attending the Academie de Musique “to listen to the worst music in the world” (Inglis 1829, 178; 1831b, 1:41; 1837, 139; 1831b, 2:68). In contrast, he is full of praise for music-making in Munich; here, “scarcely a lady in the middle ranks of life is to be found, who is not a pianist,—and the number of amateur clubs is innumerable,” while the lower classes had regular opportunities to enjoy the music of the military bands, including “the compositions of Haydn, Mozart, Romberg, or Ries” (Inglis 1837, 64). A hyperbolic “language of intensification” (Chard 1999, 84) was also applied to the music of Spain; not only was the organ of Seville Cathedral “the most perfect in the world,” contributing in the morning service to an effect “almost too overpowering for human senses,” but this was matched by executant skill, with Inglis never having “heard an organ touched with so delicate a hand, as in the Convento de las Salesas” (Inglis 1831a, 2:75, 1:258).

Levels of musical appreciation were also symbolic of a nation’s musicality. Thackeray noted that the audience for a Lablache concert in Dublin was less than a hundred, with any encores restricted to “a young woman in ringlets and yellow satin, who stepped forward and sung [sic] ‘Coming through the rye,’ or some other scientific composition, in an exceedingly small voice” (Thackeray 1857, 360). Similarly, at an opera house in Rome, Goethe described how the “seats of the German artists” were “fully occupied as usual” (a marker of cultural awareness), and how, with his compatriots, he managed to “silence the chattering [Italian] audience by crying ‘Zitti!’—first softly and then in a voice of command, whenever the ritornello to a favourite aria or number began”; the German contingent were suitably “rewarded” by the singers by their “addressing the most interesting parts of their performance directly to us” (Goethe 1970, 396).

This is an example of another common device used in travel literature to highlight “otherness”—“binary opposition,” where, “proclaiming a power of comparison conferred by the experience of travel, the speaking subject adopts his or her own native region as a constant point of reference” (Chard 1999, 40). This could work to the writer’s national disadvantage, with Inglis bemoaning the lack of patriotic drinking songs in England when compared to the Norwegians’ “Gamlé Norgé,” or comparing expensive opera admission prices in London with those of Munich (Inglis 1831a, 2:246; 1837: 57–58). Alternatively, the observer could distance him/herself by avoiding his or her country of origin in any oppositions. Describing how a performance in Venice was marred by an Italian conductor “beat[ing] time against the screen with a rolled sheet of music as insolently as if he were teaching schoolboys,” for example, Goethe added “I know this thumping out the beat is customary with the French; but I had not expected it from the Italians” (Goethe 1970, 83). Binary strategies could even be developed into ternary devices—hence, Stendhal’s ideal opera orchestra consisting of a French string section, a German wind section, “and the rest, Italian—including the conductor” (Stendhal 1959, 18). Or it could be as in Inglis’s comments on the feast of Saint Lorenzen in the Tyrol: “In France, if the music be bad, the instruments are often tolerably played; if in Germany, the execution be somewhat indifferent, the music is good; even in England, a barrel organ is found to grind in tune, if not in time; but here, music, instruments, execution, all were bad” (Inglis 1837, 244). Charlotte Eaton’s adoption of this device ranged ever more widely:

Italy is still the second musical country in the world; it must at least rank after Germany. In England … music is an exotic … entirely confined to the metropolis. … The English are not naturally a musical people. Neither in France … in Holland, nor in Belgium, in Great Britain nor in Ireland have I ever heard anything that deserves to be called music. (Eaton 1820, 3:257)

However, the most common direct musical comparison in European travel literature concerned the relative merits of German and Italian music, and opera in particular. Italy, notionally the climax of the Grand Tour and the perceived “source and center of Western civilization since the Renaissance” (Porter 1991, 164), provoked a variety of responses; if Goethe experienced a “rebirth” on entering Rome (given that Italy was “central to his conception of what Germany should be”) (Goethe 1970, 148; Beebee 2002, 323), Dickens highlighted Rome’s decline, describing a “desert of decay” (Dickens 1846, 162). Discussions of Italian music reflected this complexity. For John Eustace, although Italy represented “the great school of music, where that fascinating art is cultivated with the greatest ardour” [sic], the castrati were redolent of “ardor oftentimes carried to an extreme, and productive of consequences highly mischievous and degrading to humanity” (Eustace 1813, 1:504–505). Despite the beautiful sounds of the papal choir, the theatricality of Italian church music was problematic, hence Eustace’s warning to the traveler:

Music in Italy has lost its strength and its dignity. … It tends rather by its effeminacy to bring dangerous passions into action, and … to unman those who allow themselves to be hurried down its treacherous current … at all events it neither wants nor deserves much encouragement, and we may at least be allowed to caution the youthful traveller against a taste that too often leads to low and dishonourable connections. (Eustace 1813, 1:xxx)

These perils of emotional excess associated with a foreign musical “other” could also be identified in Italian opera, dismissed by Joseph Forsyth as an “extravagantly unnatural” genre, and by Hector Berlioz (as part of the “Grand Tour” of his Memoires) as representative of “nothing but … exterior forms … sensual pleasure, and nothing more” (Forsyth 1813, 61–62; Berlioz 1966, 183). However, not all were disturbed by Italian musical otherness. Mary Shelley noted early on in her travels that “In spite of the enchantment of the Zauberflaüte” she felt “happy and at home … at the Italian Opera, after several visits to that of their rivals in the art” (Shelley 1844, 1:177), and a later “enchanting” Der Freischütz apparently did not change her mind: “There is something very antagonistic in the German and Italian operatic schools. They despise each other mutually. Professors mostly side with the Germans, but I am not sure that they are right” (Shelley 1844, 1:255).

Similarly, proclaiming that “An opera must bear the appearance of having been made at one dash,” James Galiffe was critical of German opera’s sudden interpolations, which were “utterly disagreeable to those who remain faithful to the Italian—the only good school” (Galiffe 1820, 221); and Heine berated his own countrymen for their negativity toward Italian music:

The scorners of the Italian school … will not escape their well-deserved punishment in hell, and are perhaps damned in advance to hear through all eternity nothing but the fugues of Sebastian Bach. It grieves me to think that so many of my friends will not escape this punishment, and among them is Rellstab, who will be damned with the rest, unless before his death he is converted to the true faith of Rossini. Rossini! divino Maestro! Helios of Italy, who spreadest forth thy rays over the world, pardon my poor countrymen who slander thee on writing and on printing paper!

(Heine 1904, 231–232)

Having experienced Fidelio, Der Freischütz, La Cenerentola, and The Magic Flute in Munich, Inglis attempted to suggest complementary forms of otherness; while the music of Italy was “graceful and tender; expressive of hope and joy, and of the tender emotions; smooth and flowing; framed to soothe and tranquillize,” German music was “impassioned, rather than tender; abrupt, rather than flowing; expressive of despondency, rather than of hope; of melancholy, rather than of joy; and in place of soothing, it excites the mind to feelings of sublimity,—and diffuses over it, sentiments of solemnity and awe” (Inglis 1837, 58–59). In his more direct and extended comparison of Rossini and Mozart (both cited as representative “of the Italian school” though differing “widely in … character”), ultimately privileging a Mozartian depth over a Rossinian simplicity, Inglis underlined his own credentials as a cultural commentator:

The characteristics of Rossini’s music, are variety, grace, playfulness, and simplicity: I say simplicity; for although in his style, he is ornate, yet, in his original conceptions, he is simple;—as a simple idea is often expressed in flowery language. Rossini is never sublime,—seldom even bold; for if sometimes he seems to be the latter, it is mainly owing to the variety and rapidity of the movements. … Deep sentiment, he rarely attempts; and when he does attempt it, he fails. … The genius of Mozart seems to me of a higher order. With more elegance than Rossini, and with equal sweetness, he is master of the passions. Lofty and solemn conceptions are presented to us. … The compositions of Mozart, when he chooses to address our sensibilities, draw tears,—whilst those of Rossini rather call into our cheek, the smile of pleasure. I suspect that with the musician, as with the poet, a touch of melancholy is needed, to imbue his compositions with that greatness which survives the caprices of fashion.

(Inglis 1837, 59–60)

Music and Writing Style

Travel writers were keen not only to describe and comment on music as a cultural object but also to invoke music through metaphor or thematic parallel, indicating that the medium of prose was insufficient to convey a requisite depth of feeling. The use of musical repertoire to characterize landscape was suggestive both of a readership’s musical knowledge and of the proclivities of the author. Hence, the shameless advocacy of Handel’s music in Samuel Butler’s description of his Italian travels, Alps and Sanctuaries. While Primadengo villagers brought to mind the Dettingen Te Deum and L’Allegro ed Il Penseroso, and the valley of Ticino suggested “of them that sleep” from the Messiah, the streams of the valley of Mesocco ran “with water limpid as air, and as full of dimples as ‘While Kedron’s brook’ in ‘Joshua’” (Butler 1882, 23, 20, 260). There are parallels here with Kipling’s invocations of Arthur Sullivan’s Savoy operas in Burma (“at every corner stood the three little maids from school, almost exactly as they had been dismissed from the side scenes of the Savoy after the Mikado was over”) and Japan (“the rickshaw, drawn by a beautiful apple-cheeked young man with a Basque face, shot me into the Mikado, First Act”) (Kipling 1899, 1:207, 293), and Henry James’s characterization of a hotel scene at Cadenabbia in terms of an operatic stage (James 1909, 93); in James’s essay “Italy Revisited” (1877), as Buzard notes (1993, 210), James “smash[es] … his own picturesque fancies” by confirming that a young man, who initially appeared “like a cavalier in an opera,” was in reality “unhappy, underfed, unemployed” and “operatic only quite in spite of himself.” Similarly, Thackeray highlighted “that diabolical tune in Der Freischutz” [sic] to characterize the Irish landscape on the road to Killarney (Thackeray 1857, 115), and was overt in suggesting the inadequacy of prose—in comparison to poetry or music—to describe the natural beauty of the bay of Glaucus:

it ought to be done in a symphony, full of sweet melodies and swelling harmonies. … The effect of the artist … ought to be, to produce upon his hearer’s mind, by his art, an effect something similar to that produced on his own by the sight of the natural object. Only music, or the best poetry, can do this. … After you have once seen it, the remembrance remains with you, like a tune from Mozart, which he seems to have caught out of heaven, and which rings sweet harmony in your ears for ever after! (Thackeray 1846, 157–158)

For Mary Kingsley, the “various scenes of loveliness” that made up the Ogowé could only be described in symphonic terms—“as full of life and beauty and passion as any symphony Beethoven ever wrote: the parts changing, interweaving, and returning”—with the additional suggestion of parallels between the placement of “papyrus” and “sword-grass” and Wagnerian “leit motifs” (Kingsley 1897, 129–30). This association of musical imagery with depth of feeling can also be found in Belloc, where the sight of Como was “like what one feels when music is played” (Belloc 1902, 288); or Heine who, describing the “sublime spectacle” of a sunset in Brocken, imagined himself as part of a “silent congregation,” listening as “Palestrina’s everlasting choral song poured forth from the organ”. He also invoked music when overcome by the beauty of the ladies of Trent, noting how “that silent music of the whole body, those limbs which undulate in the sweetest measures … these melodiously moving forms, this human orchestra as it rustled musically past me found echo in my heart, and awoke in it its sympathetic tones” (Heine 1904, 40, 228). Given these examples, it is not surprising to find music at the center of a literary device associated with the unconscious mind—the set piece of the altered state or dream interlude. While Heine’s unconscious conjured up “dreary and terrifying fancies” of “a pianoforte extract from Dante’s Hell” followed by “a law opera, called the ‘Falcidia,’ with libretto on the right of inheritance by Gans, and music by Spontini” (Heine 1904, 49), the sleeping Butler indulged in the grandeur of a Handelian vision as the landscape assumed musical shapes:

And the people became musicians, and the mountainous amphitheatre a huge orchestra, and the glaciers were two noble armies of women-singers in white robes … and the pines became orchestral players … a precipice that rose from out of the glaciers shaped itself suddenly into an organ, and there was one whose face I well knew sitting at the keyboard, smiling … as he thundered forth a giant fugue by way of overture. I heard the great pedal notes in the bass stalk majestically up and down, as the rays of the Aurora that go about upon the face of the heavens off the coast of Labrador. Then presently the people rose and sang the chorus “Venus laughing from the skies”; but ere the sound had well died away, I awoke, and all was changed.

(Butler 1882, 86–87)

Elsewhere there is a more direct conflation of music and prose, where writers resorted to musical notation to illustrate their descriptions of musical otherness. Butler’s plethora of Handelian excerpts aside, examples include Inglis’s illustrations of the “wilder and uncommon character” of Norwegian song, and the music of the African boatmen in Pringle’s A Journey in East Africa (Inglis 1829, 64, 243 [facing]; Pringle 1886, 127–128; see also Lane 1836, 1:80–93). Janet Ross (1889, 185–186), explaining the importance of the tarantella in curing those infected with the tarantula bite (“I was assured that if musicians were not called in, the fever continues indefinitely, and is in some cases followed by death”), transcribed a “favourite air” that she “learnt from an old peasant” (figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Janet Ross, The Land of Manfred, Tarantella extract

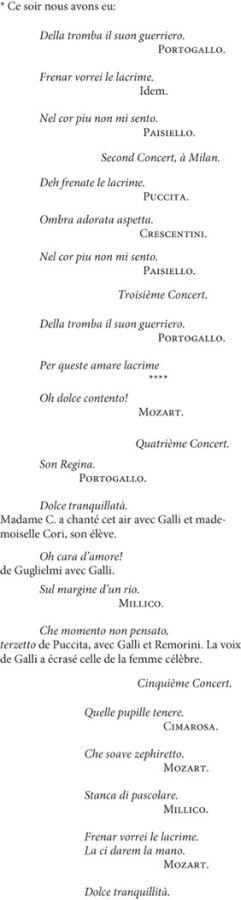

Stendhal’s Rome, Naples et Florence en 1817 went further, however, in inviting parallels between musical and literary structure and style. As Thompson suggests, given the prominence of Rossini in Stendhal’s musical discussions, not only might parallels be drawn between the importance of improvisation in their respective creative processes, but the “speed and pace” of the literary text, with its “abrupt attack, clipped transitions, and flickering ironies,” is suggestive of one of the composer’s “famous overtures” (Thompson 2012, 52–53). Thompson also highlights Stendhal’s awareness of “the possible analogy between the vertical (as well as horizontal) disposition of Western music in bars and the vertical ordering of print blocks on a page”; as a development of the musical illustrations in his Vies de Haydn, de Mozart et de Métastase (1814), Stendhal’s extended footnote describing Catalani’s relatively limited repertoire (figure 5.2) is representative of a “non-linear musical reverie” (Thompson 2012, 53–54).

Figure 5.2 Stendhal’s vertical listing of Catalani’s repertoire

The Musician as Travel Writer

Unsurprisingly, musical references are particularly prevalent in travel writings by musicians. The music critic Edward Holmes’s A Ramble Among the Musicians of Germany (1828) offered a wealth of musical description—discussing double bass tunings and orchestral forces; describing performances of opera, choral, chamber, and orchestral music; highlighting vocalists and instrumentalists (including the clarinettist Heinrich Baermann, the trombonist Carl Queisser, the cellist Josef Merk, and the pianist Johann Schneider); noting private musical societies and examples of harmonie musik; and offering opinions on composers from Beethoven to Weber; in addition to detailing the manuscript of Mozart’s Requiem and the music at Beethoven’s funeral (even transcribing the Miserere), Holmes described his meeting with Hummel—whose “unaffected simplicity” belied his status as “the most … original extemporiser on the pianoforte that exists” (Holmes 1828, 261–262). As with other travel writers, Holmes took the opportunity to denigrate foreign musical taste (“the people of Vienna” were not only “mad” for Rossini but “for his worst imitators”), and to promote music-making at home:

The plain recitative at the opera in Vienna is not well accompanied; and I heartily wish the performer could hear the fanciful and exquisite manner in which Lindley does this at our Italian Opera-house. The chords are indeed struck upon the violoncello (without that arpeggio and brilliancy, the unique excellence of Robert Lindley), but their effect is tame. (Holmes 1828, 116, 129)

While the musical references in Marquis Chisholm’s travelogue focused primarily on his own performances on piano and harmonium in Australia and the Far East (and his opportunistic composition of a “musical poem” based on the deaths of the explorers Robert Burke and William Wills) (Chisholm 1865, 14–18), Granville Bantock and Frederick Aflalo’s Round the World with “A Gaiety Girl” (1896) documented the repertoire performed on tour in America and Australia by the George Edwardes Company for which Bantock was musical director; detailing aspects of musical theatre life, Bantock’s primary frustration was that of American musical protectionism:

Musical Unions are rife all over the country. … The executive clique naturally enough favour the pretensions of their own countrymen, to the exclusion of ofttimes more deserving foreigners. … The conductor of a local theatre is permitted but little authority over the band, which is selected for him by the Union, and he is placed in the unenviable position of having to entreat rather than to command.

(Bantock and Aflalo 1896, 83–84)

Jacques Offenbach’s earlier account of a visit to New York and Philadelphia also noted how the “vast and powerful organization” of American musicians had constituted “a society, outside of which there is no salvation,” as “anyone who wishes to join an orchestra must become a member” (Offenbach 1877, 58). In his more detailed description of American musical life, Offenbach praised the high standard of American orchestras (“two rehearsals” with a 110-strong orchestra in New York were “always sufficient to insure a most brilliant rendering” of his compositions), but bemoaned the fact that there was “no permanent opera in New York, no comic opera, nor even a theatre for operettes” [sic], advising that “two operas and one literary stage” plus “a well-appointed conservatory” were needed to help “dramatic art and American composers and authors” (60, 80, 83). In addition to the familiar cataloguing of vocalists (59–60), Offenbach highlighted some of the American music critics (including Mr. Schwab at the New York Times, Mr. Connery of the New York Herald—a “musical critic of great ability,” the “brilliant feuilletoniste” Mr. Wheeler at the World, and John Hassard of the New York Tribune, “a fanatic admirer of Wagner”);3 and offered a series of character sketches of leading figures in American musical life (135–137, 141–152). These included the theatre manager Maurice Grau (1849–1907), the impresario Max Maretzek (1821–1897), the Spanish harpist Esmerelda Cervantes (1862–1926), and the conductor Theodore Thomas (1835–1905). Although Thomas had “done so much to popularize classic music in America,” Offenbach suggested that his interpretations of Rossini, Auber, Verdi, and Hérold were “without force or animation” (147).

However, in terms of composers’ assimilation of travel literature, it is the writings of Berlioz that are the most significant. His European travels, published in serial form before finding their way into the Memoires, as Inge van Rij suggests, can be understood as a blend of the “Grand Tour” tradition and “beachcomber” narratives (van Rij 2015, 39). If the German travels betray the influence of the writings of the Prussian explorer Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), van Rij demonstrates how the Second Epilogue of Berlioz’s Evenings with the Orchestra—an account of the Irish composer William Vincent Wallace’s encounters with otherness in New Zealand—may have been based on the French explorer Dumon d’Urville’s Voyage de la corvette l’Astrolabe (van Rij 2015, 14–47).

Given composers’ engagement with and awareness of literary descriptions of travel (Berlioz 1966, 6–7 confirmed that his “interest in foreign countries … was whetted by reading all the books of travel, both ancient and modern” that he could “lay hands on at home”), as I have suggested elsewhere (Allis 2012, 245–289), it is possible to apply some of the strategies adopted by travel writers as outlined here, offering the genuine potential to reassess specific musical works. Just as discussions of literary descriptions of travel have highlighted a plethora of titles (including “Sketches, Notes, Diaries, Gleanings, Glimpses, Impressions, Pictures, Narratives … Tours, Visits, Wanderings, Residences, Rambles”) which suggest intent, content, and even narrative style (Pemble 1988, 7; Genette 1988; Kautz 2000, 177), so we might view musical compositions in the same way: whether the Devon-based composer John Pridham’s relaxed Holiday Rambles (1892) for piano, Gustav Charpentier’s wide-ranging Impressions d’Italie (1890), the move from documentation to devotional journey in Liszt’s titular revisions (Album d’un Voyageur to Années de Pèlerinage), and even the use of prepositions to intimate immediacy—as in Elgar’s In the South, Henry Hadley’s In Bohemia, or Massenet’s Devant la Madone (Souvenir de la Campagne de Rome)—or distance (Strauss’s Aus Italien, Elgar’s From the Bavarian Highlands).4 The procession of nineteenth-century musical souvenirs is redolent not only of memories of events experienced as part of the travel process (Francis Bache’s Souvenirs de’Italie and the more prosaic Souvenirs de Torquay) but also of the music encountered there—hence, the national airs that form the basis of works such as Czerny’s Souvenirs d’Angleterre, Bochsa’s Souvenirs de Voyage, or Moscheles’s Souvenirs de Danemarc.

More overt examples that parallel the literary necessity of making the “other” fundamentally different from the familiar can be found in Strauss’s incorporation of “Funiculì, Funiculà” in the finale of Aus Italien under the mistaken impression that this was an Italian folk song, or Holst’s incorporation of holiday-inspired Algerian street music in Beni Mora (1908–1912)—particularly the obsessive reiteration of the musical material in the final movement, “In the Street of the Ouled Naïls.” Related examples include Liszt’s incorporation of a melody by the sixteenth-century composer Louis Bourgeois (c.1510–1561) in “Psaume—de l’église à Génève” at the end of the first book of the Album d’un voyageur, or the aim of the paraphrases in the third book to represent “a series of airs (‘Ranz-des-Vaches, Barcaroles, Tarantelles, Canzone, Hymns, Magyars, Mazurkas, Boleros’), which I shall elaborate to the best of my ability, and in a style appropriate to each, which shall be characteristic of the surroundings in which I have stayed, of the scenery of the country, and the genius of the people to which they belong” (Liszt 1916, preface). Similarly, “Venezia e Napoli” from the later Années de Pèlerinage included paraphrases of Peruccini (“La biondina in gondoletta”), Rossini (“Nessun maggior dolore” from Otello), and Cottrau in “Gondoliera,” “Canzone,” and “Tarantella.” How authentic these examples of otherness are is less important than their being labeled or perceived as representative of a musical “other”—whether the striking “melopées ardentes” of the sixty-six–bar passage on unaccompanied cellos that opens Charpentier’s Impressions d’Italie (figure 5.3), the “canzone entonnée a pleine voix par le mulattiere” of the cello theme in the third movement, “A Mules” (whose minor key reflects the melancholic trope of the musical vernacular described here), or the musical “vibrations éparses” that populate the finale (Charpentier 1900, preface).

Figure 5.3 Gustave Charpentier, Impressions d’Italie, opening

As Chard reminds us, otherness can be created “through some form of rhetorical ‘duperie’”—hence, Elgar suggesting that his “Canto popolare” episode from In the South was an imperfect aural transcription, but later admitting that he had manufactured the tune himself (Chard 1999, 2; Newman 1906, 171).

Of the additional literary strategies highlighted here, a binary opposition is clear in Elgar’s musical contrast between the chromaticism of “E[dward] E[lar] and family musing” and the diatonicism of the Italian landscape in In the South (an overt North/South musical divide), and the injection of a typically Elgarian sequence within the Turkish religious otherness of In Smyrna (figure 5.4)—both examples suggestive of the composer’s “presence” within the musical scene to add authority by being on the spot. Similarly, in the opening movement of Strauss’s Aus Italien, the E-flat major theme, designated as “memories of home” by Richard Specht (Strauss 1931, preface), impinges upon the G major of the Italian scene; these binary tensions have parallels with Berlioz’s “negotiations of the relationship between civilisation and barbarism” in his song “La captive” (van Rij 2015, 42). Hyperbole can be identified not only in the sustained musical excitement at the opening of Elgar’s In the South (“Maybe the exhilarating out-of-doors feeling arising from the gloriously beautiful surroundings”)5 but also in the exuberant representations of Napolese entertainments in the finales of Charpentier’s Impressions d’Italie and Massenet’s Scènes napolitaines; there are also examples of the past impinging upon the present in the second movement of Aus Italien, “In Roms Ruinen” (“Fantastic images of vanished splendour, feelings of melancholy and sorrow amid the sunshine of the present”; Strauss 1931, preface).

Figure 5.4 Elgar, In Smyrna, mm. 18–25

While the absorptive power of the foreign scene in literary descriptions of travel finds obvious parallels in Saint-Saëns’s Une nuit à Lisbonne or Massenet’s Devant la Madone, structural models in travel literature—where a succession of first-person chapters invoke successive scenes of otherness for the literary gaze—have musical equivalents in the separate scenic movements of works such as Raff’s Hungarian Suite (“At the border”; “On the puszta”; “Amongst a parade of the Honvéd”; “Folksong with variations”; “At the czárda”—even if this was representative of second-hand travel); Saint-Saëns’s Suite algérienne (“Prélude (En vue d’Alger)”; “Rhapsodie Mauresque”; “Rêverie du soir (à Blidah)”; “Marche militaire Française”); Massenet’s various musical Scènes (napolitaines, hongroises and alsaciennes); d’Indy’s Tableaux de voyage, ops. 33/36, Poème des rivages, and Diptych méditerranéen; the contrasting locations of Strauss’s Aus Italien; the progression of genius loci and cultural artifacts in Liszt’s Années de pèlerinage. The scenic division within the one-movement structure of In the South is offset by the recurrence of Elgar’s opening motif, providing authorial unity.

Just as final chapters of travelogues often indulge in nostalgic musing that revisits significant moments of the foreign experience, so the conclusion to the op. 33 thirteen-movement piano version of d’Indy’s Tableaux de voyage (“Rêve”) recalls both a fragmentary reference to “Lac vert” and a fuller return to the opening movement (“?”).6 We might even be encouraged to explore music’s mirroring of specific travel texts—whether Joseph Schneer’s guidebook Alassio: “A Pearl of the Riviera” and Elgar’s juxtaposition of the tramp of the Roman legionnaires, “strife” (“a sound picture of the strife and wars … of a later time”), and a return to reality in In the South (Allis 2012, 276–277); or as David Larkin suggests, Strauss’s invocation of a boatman’s song in the third movement of Aus Italien (“Am Strand von Sorrent”) and Goethe’s description of fishermen in Italienische Reise (Larkin 2009, 102–103). Given the titular connections often suggested between Liszt’s Album d’un voyageur and George Sand’s Lettres d’un voyageur, one might invoke further parallels between the instability of these texts in relation to their publishing histories and their shared central themes of music’s close relationship with Nature and its primacy as an artistic form (Garnett 1994; Searle 1954, 23–24).7

Music therefore had a prominent place in nineteenth-century travel literature, not only in terms of documenting the musical “other” but also in allowing authors to attain cultural accreditation for their discussions of the relative merits of composers and performers, notions of musical progress and evolution, and the competing musicality of nations. While tropes of melancholy, monotony, simplicity, animality, and discord were utilized for various purposes, literary strategies used in relation to other cultural artifacts of otherness (art, architecture, landscape, food)—including hyperbole, binary opposition, and on-the-spot reportage—were applied effectively in a musical context. As a marker of emotional depth, often associated with the unconscious mind, music’s status as a meaningful art within nineteenth-century intellectual culture was promulgated through thematic reference, and the visual juxtaposition and conflation of musical and literary texts on the printed page confirmed a close music-literature relationship in this period.

However, we should not ignore the implications of this rich discourse for musical composition; just as composers and musicians were inspired to pen their own literary descriptions of travel, so their musical works can be interrogated meaningfully in terms of those same literary strategies. This targeted hermeneutic tool can help us to explore not only how musical representations of foreign travel were communicated but also how they might be further understood.