Drowning in Cash

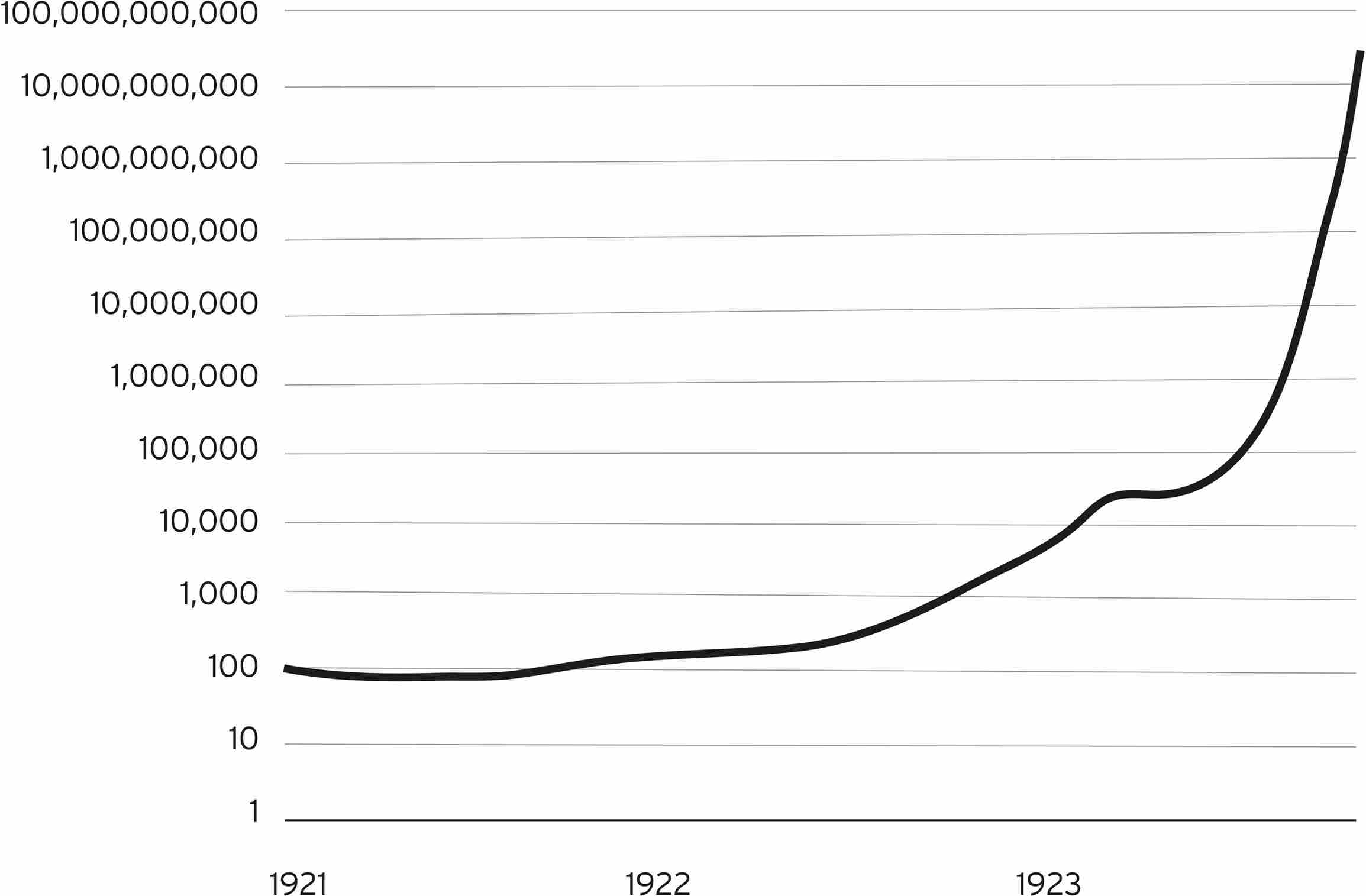

One of the specters that haunts economics is hyperinflation. Central bankers’ nightmares feature grainy black-and-white photos of women carting wheelbarrows full of cash through the streets of Weimar Germany to buy bread. Runaway inflation arises from a confluence of factors, but the most notorious culprit is a government that prints too much money. Loading up the money supply devalues the currency, requiring the government to print even more, further devaluing the currency, etc. In Germany after World War I, prices rose so fast that restaurants stopped printing menus—they went out of date between the appetizer and dessert.

Could it happen here? The U.S. government spent its way out of the Covid recession, making an unprecedented injection of money into the economy. It worked, but printing cash to solve problems is a hard habit to break. And by late 2021 it was clear that inflation was on the rise. A little inflation isn’t such a bad thing; for debtors, it has a bright side—when money is worth less, debts are, too. But hyperinflation destroys economies.

It may be that modern economies are not subject to this risk in the same way early industrial societies were. And certainly, our political climate, as bad as it might feel, is nothing like that of 1920s Germany. At that time, Germany saw hundreds of political assassinations and occupation by the French military, which was seeking reparations payments. But “this time is different” are famous last words.

84

Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany

Annualized rate of inflation, log scale

Source: Financial Times.