A FEW MORE LINES FROM THE AUTHOR

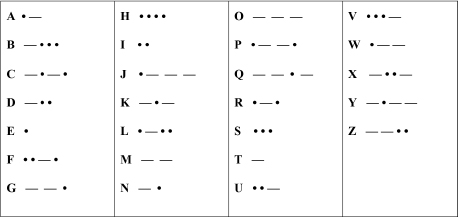

There has been positive proof of time travel ever since 1836, when Samuel Morse invented Morse code. Ever since then, had anybody bothered to look, they would have found Morse code messages in the three-thousand-year-old hexagrams contained in one of the world’s oldest books, China’s I-Ching: The Book of Changes.

Nobody bothered to look.

It doesn’t surprise me that it was two middle-school kids who finally made the discovery. Middle schoolers are still intellectually curious, and they have not yet been taught that some things are impossible. (Or, if they have been taught this, they know enough not to believe it.) Finding Morse code in the I-Ching is the same as finding a cell phone in King Tut’s mummy case, or a fossilized snow-blower in the La Brea Tar Pits, or a battery-powered nose-hair trimmer in the ruins of Machu Picchu. This is why the title is The Book That Proves Time Travel Happens. You can’t argue with hard evidence.

What do we know about the time traveler who created the I-Ching hexagrams and their cleverly concealed Morse code messages?

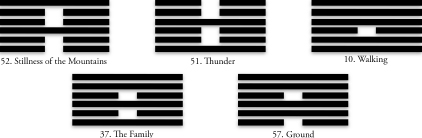

We know a lot. For one thing, he made his base in the mountains. Hexagram fifty-two, called Stillness of the Mountains, contains the Morse code for base. He was also an avid follower of the weather—hexagram fifty-one, called Thunder, contains the Morse code for sleet. He liked to leave his dwelling for an occasional stroll—hexagram ten, Walking, contains the Morse for out. And his parents apparently came from two very different backgrounds—hexagram thirty-seven, The Family, contains the Morse for mix.

And, how appropriate is it, considering China’s notorious rainy season, that hexagram fifty-seven, known as Ground, should be turned by its Morse into mud?

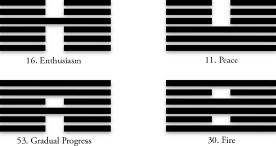

If you’re thinking this is all just coincidence, our time traveler was sometimes exuberant—hexagram sixteen, Enthusiasm, is full of sass, as so many of the enthusiastic are, and when he was at peace, he hummed—hexagram eleven, Peace, contains hum—and he felt that change for the better almost always takes place in small increments, otherwise why would hexagram fifty-three, Gradual Progress, contain the tiny measurement of mites? He also, quite sensibly, preferred his seafood cooked, rather than raw, since hexagram thirty, Fire, is full of tuna.

Added to the hexagrams mentioned earlier in the book—Trouble containing erase; Observing containing miss; Decay containing dead; and, most telling of all, Travel containing times—we have irrefutable proof that someone from the future visited, and probably made his home in, China at the time of the Zhou dynasty.

I am eagerly awaiting notification that I have won the Nobel Prize for time-travel research. To my mind, there are no other contenders.

Exactly half—thirty-two—of the I-Ching’s sixty-four hexagrams contain Morse code messages that relate to the topic of the hexagram they occur in. The I-Ching is all about opposites: yin versus yang, chaos versus order, hello versus goodbye. So, whoever created the I-Ching made a deliberate artistic choice to put messages in only half of the hexagrams: meaning vs. nonsense. Of the thirty-two nonsense hexagrams, most contain no messages whatsoever, while a few contain gibberish. (There is, for instance, no sensible reason why hexagram twenty-one, Chewing Up and Spitting Out, should contain the Morse code for Tibet, unless the I-Ching’s creator was making a veiled critique of modern-day China’s internal policies.)

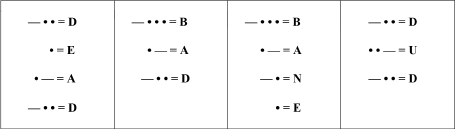

A few of the hexagrams contain more than one message, depending on how the dots and dashes are read. Here, for example, is hexagram eighteen, Decay:

It can be read from top to bottom in four different ways:

All four words can relate to Decay, but dead is the most appropriate. The other three choices are just the I-Ching’s creator showing off, something he did fairly often. (For instance, hexagram fifteen, Modesty, contains either the Morse code for hers, or seers, and since it would be sexist to suppose that modesty is only appropriate to the female, he had to have meant that seers—fortune-tellers such as himself—should show a little more humility, which he easily could have done by being a little less clever.)

Do I believe all this?

Of course.

So should you.

It will make your world that much more intriguing.

The point here—or maybe it’s a dot, possibly a dash, maybe even a dot and a dash—is that patterns are everywhere. Some patterns are easy to find; we’re all aware of them. Other patterns are more complex, and we need artists, musicians, writers, and scientists to find them and point them out to us. Usually, once these people show us the patterns, the patterns make our lives a little richer: We say, cool, I like that song; this painting moves me; what you just said helps me understand the universe a little bit better, or it makes me laugh, or both.

When the scientist Sir William Ramsay first isolated the element helium in 1895, he did it by studying the patterns in something called a spectrogram. Spectrograms are a series of lines; they look like I-Ching hexagrams on steroids. Sir William’s discovery of helium made modern MRI medical scanners possible, and has resulted in birthday balloons being 98 percent less droopy. (I like to think that Sir William ran out of his laboratory shouting, “I’ve discovered helium! I’ve discovered helium!” but that’s just me.) His discovery would never have been made without his ability to recognize patterns.

The artist Pablo Picasso once removed the seat from a bicycle, welded a set of bicycle handlebars to the seat, hung it on a wall, and everybody who saw it said, “Ah! the head of a bull!” The handlebars became the horns, the seat became the bull’s long face. The pattern was there; Picasso saw it first, and once he pointed it out, everybody could enjoy it, except possibly the guy who owned the bicycle. What Picasso did is called a visual pun. (People who hate puns call it found art.) It is very similar to seeing the dots and dashes of Morse code in the hexagrams of the I-Ching. (Am I comparing myself to Picasso? No, but I am saying my bull is every bit as good as Picasso’s bull.)

Patterns are everywhere. In clouds, in junkyards, in human behavior. We read to find patterns. If you’ve read this book, you’re a pattern-seeker, and that’s a very good thing to be. Some of the patterns in the book were deliberate—puns form a type of pattern; stories of prejudice through the ages form another—but I’m sure there are patterns within this book that the author was unaware of. Different readers will see different things. This is how books work.

Dear reader, new patterns are out there, waiting to be found, and waiting for their finders to show them to the rest of us.

Who will find them?

I’m betting it’s you.