1

Every Alaskan has a bear story. Should I start with a true one of mine? “The grizzly bear stood there, five feet away, his enormous head visible through the thin plastic sheet over the window in the old cabin door. He was turning the doorknob with his teeth. In a moment he would burst through.” Naaah, I’ll tell about it later.

I first saw the 600-mile length of southeastern Alaska from the air and then on shore while on a business trip, as part of my job counseling high school students about career choices. As we landed and took off from the five main towns, I looked down on islands: tiny one-tree rocks; islets with sand beaches and coves; a 10-acre isle with a pond, huge trees, and a point for watching both sunrise and sunset; islands with no one on them.

An island is a finite thing, a concept of romance and solitude, from Calypso’s island, Ogygia, in Homer’s Odyssey to Suvarrow in Tom Neale’s An Island to Oneself. Southeastern Alaska has more than a thousand islands. Four of the five largest towns are on islands.

For years I had searched for a combination of mountains, wilderness, and sea, and here it was. Clear quiet water, snowcapped ridges and peaks, small bays – all in the Inside Passage, sheltered from the storms of the open North Pacific. Ferries, freighters, fishing boats, and cruise ships all used it. So could I. Most of the land was within the boundaries of the 16-million-acre Tongass National Forest, the largest national forest in the United States.

There seemed be total wilderness only 10 miles away from any town, and the towns were more than 100 miles apart. That left a lot of space to paddle and explore and camp. Since 1967, between jobs, or whenever I could squeeze in a vacation, I’d been voyaging in inflatable canoes. Most of my trips had been along the more remote shores of the Hawaiian Islands: Kona, Na Pali, Hamakua, and Hana, with many along the 3,000-foot-high cliff coast that forms the north shore of Moloka‘i. I’d written a book about that coast, Paddling My Own Canoe – now in its ninth printing. There had also been paddle trips in Samoa, Norway, Greece, Scotland, and Maine.

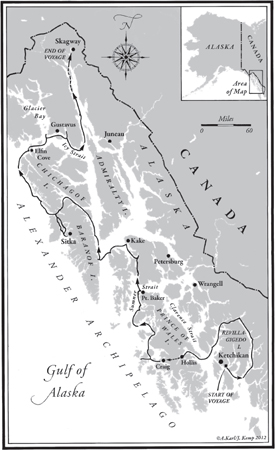

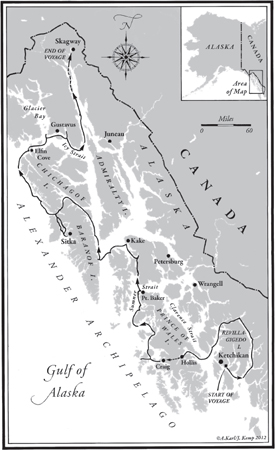

The choices were clear. I could paddle solo from Seattle to Skagway, an established route for fishing boats, ferries, and gold seekers. The two names together had a twangy alliteration. Both were Native American, reminders of the Haida and Tlingit people who had paddled cedar canoes for centuries along the misty shores. Skagway was a suitable destination. A classic photo showed hundreds of men toiling up the icy slopes of the Chilkoot Trail who later paddled down the Yukon River to the goldfields.

The second choice would be to go gunkholing, as boaters say, prowling in and out of tiny coves, omitting all of British Columbia for now, and instead starting at Ketchikan, the southernmost town, and meandering north to Skagway, the northernmost. I could connect a roundabout route of hot springs, old cabins, small islands, and resupply towns. I could trace parts of the historic voyages of Cook, Lisianski, Vancouver, and Muir; find the locales of some favorite books; search for mushrooms; and try to communicate with such endearing animals as whales, otters, and loons. I wasn’t yet figuring to communicate with grizzly bears.

A theme to weave into the Alaska trip would be one I’d practiced on each of my previous expeditions. Part of the fun and art of long-distance paddling and camping trips has been the reverse twist of being able to carry elegant cuisine instead of gruel and granola – each week’s international menu of delectable meals weighing no more than 10 pounds. In Alaska I could also add berries, mussels, and salmon.

On either route, the distance would be more than 800 miles. If I launched from Seattle, I’d be paddling north inside the protection of Canada’s Vancouver Island, with cities and towns, for the first 200 miles, then following the long narrow channels to Prince Rupert. I would then recross the Canadian border and hug the shores up through the Alaska Inside Passage.

If I made the other choice, starting at Ketchikan and routing via Sitka, I’d have no cities or suburbs; there would be some inside waters, but also open sea north of Sitka. In Hawai‘i, I’d had strong winds, rough seas, two-foot tides, and dumping surf, but 74-degree water, and I could hug the coast around each island. Alaska had calmer seas and rarely any breaking surf, but 48-degree water and often a range of 20 feet between low and high tide. En route to Sitka I couldn’t always hug a coast. There would be four dangerous straits to cross, each one 8 to 12 miles wide. Either choice would be a race against time. I couldn’t start until June, and by the end of August I needed to be back on the job in Hawai‘i.

Once I’d visualized the themes and the places and put the choices into words, the decision made itself. I would go meandering, starting in Ketchikan.

My nine-foot-long inflatable canoe would be some sort of first, the smallest boat to go the distance, an impertinent toy compared to Indian cedar-log dugout canoes and modern fiberglass kayaks. It appeared to be a mocking spoofery of all serious expeditions.

“You’re paddling 800 miles in Alaska in that?” said a man on the beach one day in Hawai‘i.

He looked at the limp, shapeless roll of plastic on the sand. I attached the hose of the air pump to a valve. “You must be a real nut!”

The plastic canoe squirmed slowly out of its wrinkles into a tube shape. I moved the hose to the other valves.

“Where’s the Donald Duck head and clown feet?”

I kept pumping. The second side and the hull assumed a boat shape, a bit like a canoe-shaped doughnut. Eighteen pounds, bright yellow, with red, white, and blue racing stripes down the sides. Its cruising speed was two knots. Racing stripes, indeed!

Why was I using this tiny boat? The answer was clear, if only to me: I already owned it; it would roll up into a duffel bag that I could take on the plane from Hawai‘i; I had paddled enough rough open-ocean miles in it to know that it was seaworthy; and, above all, it was light enough to carry by myself up the beach and above high tide each night.

My yellow color scheme was reinforced when the catalog order of foul-weather gear arrived. I put it on and walked around my Hawai‘i living room. The coconut palms swayed in the warm trade winds outside, but in oilskins and sou’wester I was on deck in Conrad’s Typhoon, battered by a cold Cape Horn sea with Dana before the mast, and racing for the America’s Cup.

I laughed at the images and knew again that I had two incompatible careers. One was a full-time job: “Education Coordinator,” the job description said, but I was also a vocational counselor, helping people decide what to do with their lives – which only led to my wondering whether I knew what to do with my own. The other job was roaming off to some place I’d read about, some nook of the world as isolated as I could get to, given the bounds of little money, an aversion to sponsors, and a strong preference for going alone. Recently, I’d taught a series of how-to-kayak classes for the University of Hawai‘i and had given slide shows about the vagabond career.

I asked for two months’ time off from the job, leave without pay. I didn’t need to get “away.” I needed to get “to.” To simplicity. I wanted to be lean and hard and sunbrowned and kind. Instead I felt fat and soft and white and mean. Years of a desk job in a bureaucracy can do that even if you like the job. Summer was a school vacation for the high school and college students and teachers I worked with, and a less busy time on my job, so the request seemed reasonable.

I ordered 24 ocean charts from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and 49 U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps. The topographic map for the Port Alexander C-3 quadrangle was a joy. Some musicians can look at a sheet of music and hear the melody and the rhythm. Their faces light up as they read down the page, hearing it so clearly. This map told me of the mountains and bays of southern Baranof Island.

“Look there at the head of Gut Bay,” I said to myself. “You could follow the stream up to the lake, but I wonder how much underbrush there is. Look, you could bushwhack this pass over to the next lake and the next.”

My excitement was building.

“That stream would take you down to the Great Arm of Whale Bay and you’d be across Baranof Island.” (I found out later that small planes take this route across Baranof Island when its higher peaks and passes are clouded in.) “Plotnikof, Rezanof, and Davidof Lakes. Who were those Russians and who named the lakes? Three Forest Service recreation cabins are on the lakes, so the fishing must be good, but I can’t paddle to them or even hike. No trails and a thick forest. I’d have to charter a seaplane. Look at all the glaciers. How steep Mt. Ada is, and it’s 4,000 feet high. Maybe you could climb it from this shoulder twisting up to the south from the shore of Gut Bay.”

A notation on the map showed a hot spring in Gut Bay. As closely as I could from the brief description, I marked its location, along with eight others that I could reach on my meandering sea route.

My request for the two-month leave came back disapproved. I went home and looked at the Five Year Plan on the wall: income and outgo for each year, the list of important home factors, the morale-building list, the 25 things I most wanted to do in order of importance. Paddle Alaska, number one. I walked into the bathroom and looked at the familiar person in the mirror.

“Getting older, aren’t you, lady? Better do the physical things now. You can work at a desk later.”

The next day, I handed in my resignation, effective in two months. Sometimes you have to go ahead and do the most important things, the things you believe in, and not wait until years later, when you say, “I wish I had gone, done, kissed …” What we most regret are not the errors we made, but the things we didn’t do.

My voyage was now more open-ended, limited not by the job but only by the arrival of the Alaskan winter, in September. All four children were grown, I had been divorced years before, and I had saved enough money to last for more than a year. I was truly free.

I started planning the route in detail, using three main sources: Exploring Alaska and British Columbia, by Stephen Hilson, Coast Pilot #8, from the NOAA, and the map of the Tongass Forest that showed the 50 sea-level Forest Service cabins.

During those next weeks I reserved and paid for cabins where I could stay for 10 nights of the 80-plus days the trip would require. I mailed some of my gear to friends in Ketchikan, the capable Castle family. Each evening, as I drove the 30 miles home from the job, out through the traffic from the Federal Building in Honolulu, down through the pineapple and sugar cane fields, I planned the evening’s work. I dried food and packed it, along with the charts and maps, using a separate box for each segment of the route, then mailed these resupply boxes to myself at five post offices that I had never seen – Ketchikan, Craig, Kake, Sitka, Gustavus. On each box was a note: “Postmaster, please hold for paddling expedition to arrive approximately (date).”

I added hours on the job, preparing for my replacement. I packed away the chaos at the old beachfront home, making it ready for a summer tenant, the rent paying my plane fare. I made copies of the daily route, one for family and one for the Castles, so they’d know where to start a search if I didn’t check in along the way. Every detail was taken care of, down to the pencil that had one-inch notches on one side to measure a mile on the topo maps, and notches on the other side to measure a nautical mile on some of the ocean charts.

On a Friday in June, I cleaned my desk and walked out of the office. All was ready. At 11:00 that night I was on the plane heading north.

Adventure. The word is ad-venture, to venture toward. No big declarations of peril, challenge, daring, conquest. No guarantee of making it. Just trying toward.