12

The morning body had the usual stiffness for the first half hour’s paddling, but soon warmed up. I should have spent two minutes stretching. Two months ago, my pace had been 20 strokes a minute. Now it was 30.

Out and around the first point, then past Point Dougherty with big swells from the south; Hawai‘i was out there, too, in a straight line 2,000 miles away. A bit of shelter in the lee of the Porcupine Islands, then swells again. Once past the rocks ahead I would be halfway to Point Urey. It was hard to maneuver because of the thick kelp. For the first time, I was certain I was seeing sea otters, not seals, as feet showed, not fins, when they humped over to dive. The sun had been shining all morning, and a strange event was happening: Sweat was dripping off my nose as I paddled through the kelp, the first sweat since Hawai‘i.

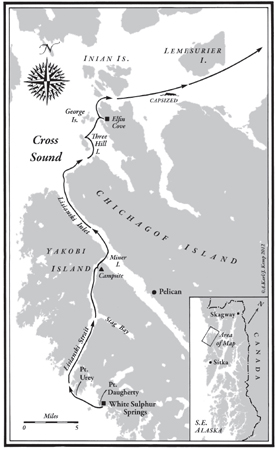

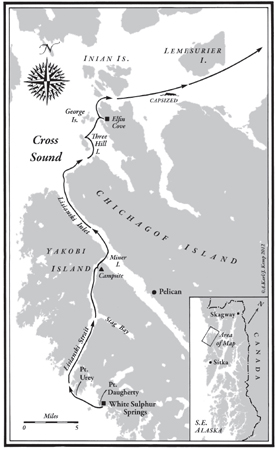

On into the strait named for the Neva’s captain, Urey Lisianski, who also gave names to many of the places near the coast in Alaska. I had a tailwind, an incoming tide, and clear views of the mountains. Far ahead was the snowcapped Fairweather Range with its 15,000-foot peaks.

Salmon had been jumping, and I rigged the fishing gear to troll a line. In three minutes a fish struck hard. Since hooks, fish spines, and inflatable boats are not an advisable mix, I braced the pole between thigh and boat, looked for the nearest beach, and paddled to shore. One hand held the jerking pole; the other paddled, then looped the lifeline to a rock. I played the fish toward the shore while using my free hand to pull the camera off my neck, screw it to the tripod, and set the self-timer to record shots of the action. That eight-pound fighting coho, finally landed and bagged, was going to provide several lunches and dinners.

The wind and tide stayed my way for another two hours, then both slowed. I kept watching the kelp. Rooted to the bottom, the long stems reached up to the surface, buoyed by a bulbous air sac; the long fronds streamed in the direction of the currents, flowing like Rapunzel’s golden hair.

Just short of the charted light at the north end of the strait was a campsite. A stream, plenty of wood, and the shortest haul in a month. There was a strange formation of wispy torn clouds to the west. I built a fire on layers of dry plywood and scrap metal, as a wet moss base doesn’t work, and after Devils Elbow cabin I knew now about organic soil that burned. I seldom build a campfire; it insulates me from the night and the natural world and takes away my night vision, but occasionally I do want the fire warmth that humans have been building for half a million years. I also needed to smoke some salmon. Earlier I had spotted a five-gallon can on shore and brought it along. One end was gone. Perfect. I punched holes in both sides of the can and wired in one side of my grate. Holding the grate in place with one knee, I placed the marinated chunks of salmon, then wired the other side. The fire was down to coals, and I added sticks of half-green alder, placed the can on top, and chinked around the base with wet earth.

Off to bed, with the tent across the stream from the smoke oven. It didn’t feel like bear country, and there was no evidence of any. Nineteen easy miles today.

The red light marking the mid-strait island had been flashing at five-second intervals all night, but at dawn it was obscured by solid fog. So that’s what those clouds meant. The other side of the strait was invisible, half a mile away. Breakfast, then checked the smoke oven. The salmon was perfect, a soft-smoked product that would keep only for a week or so, just long enough to eat it all.

I left in the fog on a magnetic north course, the compass between my knees. A mountain ridge showed softly ahead, and a sun dog, an ellipse of light like a rainbow, lay over the water to the left. I passed Miner Island, where the tides meet and change. The tide was going out now, down Lisianski Inlet, but a northwest wind came up. I crossed the inlet and decided to have lunch and wait out the wind. The sun came out, and so did many fishing boats. There was a clear view all the way southeast up the inlet to the village of Pelican, an unlikely name for a town here, as there are no pelicans in Alaska.

Down the inlet I paddled, around the white water at the base of the rock steles of Column Point, and out into the rolling swells of Cross Sound. Far out to the northwest, beyond Cape Spencer, was the open sea route to Lituya Bay, where an earthquake and a gigantic landslide on July 9, 1958, had caused a 50-foot displacement wave to rise up the spur ridge across the bay, stripping it of trees to a height of 1,720 feet. Three boats were in the bay at the time, and two miraculously survived. Four years later, I would hear the story of the wave and of one of those boats, the Edrie, from its competent skipper, Howard Ulrich, who had been on that boat with his six-year-old son and who now was captain, cook, and mate of the Forest Service boat Sitka Ranger. The Lituya Bay story is also well told in the book Land of the Ocean Mists, by Francis Caldwell and Robert DeArmond, and also in Wildest Alaska, by Philip L. Fradkin.

Beyond Lituya was the long route to Yakutat, with rows of breaking surf, making it impossible to land and launch my boat. That would be the outside route to the northwestern point of the Alaskan Panhandle. I was going the inside route to the northeastern point, Skagway.

I turned right – “Starboard, you lubber,” I corrected myself – heading for the Elfin Cove settlement. Ahead was a rock island covered with gulls. As I sat watching, a 15-foot whale with a hooked dorsal fin rolled by for a quick glimpse of this yellow animal. It looked like the minke whale on my sheet of silhouette identifications. I paddled on to Three Hill Island, with its clear water and eroded columns.

The crew of a powerboat, the Hunky Dory, asked if I needed help.

“No, I’m fine. Just taking photos.”

Ten minutes later, a troller with poles spread at a 45-degree angle and lines running back from the gurdies, the power winches, asked if I wanted a tow. These Elfin Cove people were a rare breed!

“No, thanks very much.”

I should have accepted. He was the first fisherman to invite me. I couldn’t learn about Alaska-style fishing and how it differed from the Southern California albacore fishing I had done for those three years long ago unless I were aboard. But towing is a risky business: hooks, lines, cables, the curling waves of the wake, all could tear and dump my rig. Better to stay solo at my own slow pace.

I was tiring now, knowing I was overdoing it, but paddled slowly across the three miles and into the narrow entrance of the cove. Civilization again, the first town since Sitka, but the year-round population of about 40 wasn’t city size.

At the dock I tied up between skiffs and walked up the ramp. Tony, the efficient cook at the Elf Inn, made a $6.50 hamburger that was worth the price. I laughed to realize that even after my exotic haute-cuisine meals, I still went straight for a hamburger when I came into town.

A pair of booted fisherman on the next swivel stools asked, “You come off a boat?” I nodded and pointed an elbow toward the small yellow craft.

“Where’s your big boat?”

“That’s it.”

“Were you the one out in Cross Sound?”

Mouth full, I nodded.

“Where’d you come from?”

I mumbled, “Ketchikan.”

“In that?!”

Nod.

“Alone?”

“Yes.”

After they had commented on insane women, I got good advice about the next day’s crossing of Icy Strait.

A buyer barge was at the end of the floating dock with a supply store for the fishing boats. While buying my own supplies I had my first look at a king salmon, a very impressive animal, and it only confirmed my decision that I would limit my own fishing to the smaller species and that I’d keep my knife handy to cut loose anything that felt like this size.

Next morning I mailed off the kelp pickles, then wandered up to meet Augusta and Roy Clemens, whom I’d heard about back at Point Baker. They were another of the old-time capable Alaskan couples scattered throughout the southeast in the small settlements or in isolated nooks. The Elfin Cove street was a boardwalk clinging to the cliffside, maintained by the highway division of the State of Alaska. I walked along the planked lane past old wooden houses. The boardwalk became a trail; the houses perched on the slope. There were spruce needles underfoot, ferns and berries along the way in the dim light under the trees. Augusta was accustomed to visitors; she continued cutting halibut and salmon into three-inch squares to smoke over alderwood. Kelp pickles, pies, and cookies were on the table, and the scent of freshly baked bread came from the ovens. I had samples of warm raspberry jam, good coffee, and took pages of notes for feeding myself even better.

My six kayaking friends arrived in Elfin Cove and arranged a ride for themselves on the Kris, a fishing boat, across the treacherous South Inian Pass and Icy Strait to Glacier Bay. I paddled off solo in the early afternoon to catch the incoming tide through the Pass, where the outgoing current can reach nine knots. I went through at low slack with an imperceptible current, and headed toward Lemesurier Island to camp. A few miles later, the Kris with its crew plus the kayakers caught up.

I was holding a line from their boat, talking to the group, deciding whether to paddle or ride or tow for a bit. The skipper picked up speed only slightly, and I slacked off on the line to fall back into a side tow. It was just enough to let their heavy boat’s bow wave come back between my light craft and theirs, enough to lift my port side and roll me neatly and precisely upside down.

I came to the surface instantly, tethered to my boat by the lifeline over my shoulder. The water was numbing; Icy Strait it was, indeed. The boots didn’t pull me down, but they were full of water and sliding down, about to come off and sink. The bags of gear were still under the boat. I was on the same side as my lifeline. I needed to swim around to the other side, leading the line up and across the bottom of the boat so as to pull the line taut and flip the boat upright. I swam to the end of the boat, keeping my knees bent tightly to hold the boots on, thinking I could flip it from the stern, but I couldn’t get enough leverage. Hell, just wait.

The fishing boat circled and was back to me in two minutes, the kayakers standing along the side, aghast. I handed up the boots, then the bags, paddle, and the line to my boat, and then climbed up, and we pulled the boat over the side to the deck. Judy fired up the cabin’s oil stove, and I went below to strip and rub dry, shivering violently. I unpacked my clothes bag, put on the dry wool underwear, a sweater, wool pants, dry socks, and dry shoes. Nothing was lost, not even the wool cap, only a bit of pride.

It was a good lesson. I needed to rig a clip loop for the boots and hang it from the boat. Alone, I’d need to get the gear out from under the boat, or flip the boat up and off the gear to right it. I needed to hold the paddle line and lead it, too, over the boat to assist in flipping it. These inflatables had three major safety advantages over fiberglass boats. They rested on their buoyant sides when capsized, draining out all the water. When flipped upright, no water remained inside. Second, they were far easier to climb back into than most rigid boats, with their narrow cockpits and rolling hulls, where you always felt you needed knees that bent the other way. Third, these boats had their own buoyancy. You didn’t have to take up cargo space with air bags, or use an alternate system of weighty bulkheads, which often seemed to twist and leak through their walls or through their hatches.

The decision to paddle or to ride the remaining 18 miles past Lemesurier Island and on to Glacier Bay had been made by my own error. I kept watching the rough seas of Icy Strait, and was glad to be aboard.

“When you get to Skagway you can’t count this as mileage paddled, Aud. For sure not.”

I kept reliving the capsize in my mind. All the literature said you could live for 30 to 45 minutes in 40-degree water, depending on your body fat, wool clothing, and ability to hunch into a fetal position so as not to lose heat from armpits and groin. But it might be only 10 minutes until I was so numb that my body could not respond to my mind’s commands. I had often climbed back into the boat in Hawai‘i, but there I was wearing fins and bikini, so that I could roll out and swim along, towing the boat while viewing the underwater scene. The idea then was also to use some leg muscles as a change from arm-and-shoulder paddling stress.

I had better practice capsizing while wearing boots, pile pants, shirt, foul-weather bib pants and jacket, gloves, and a cap, with all the bags of gear in the boat. I had to get the boat upright, then get into it. To slide into the boat I had to first kick my legs up parallel to the surface, reach across and push down on the far side while I slid in across the near side. Mental rehearsals were fine – I was gyrating in body English as I thought through the steps – but the brain-muscle circuits had to be trained also. Practice it a dozen times, in 20-knot winds, with all gear and cold-water clothing, until you don’t have to think, just act.

At the dock of Bartlett Cove in Glacier Bay National Park, I thanked the boat skippers, contributed for fuel, then offloaded my gear and paddled down to the parklike campground. I walked back carrying a soggy load of clothes for the lodge’s washer and dryer, then back again to set up camp, putting most of my food into the log cache, fortified against bears. Tent and tarp up, I walked the winding trail on a different route to the lodge, noting wild strawberries near the beach.

Away from shore it became a fairy-tale forest. Less than 200 years before, the land had emerged from under the retreating glaciers. When Captain George Vancouver sailed through Icy Strait in 1794, still searching for a Northwest Passage to connect with the Atlantic Ocean, there was not even a bay to be seen; the five-mile-wide mouth of Glacier Bay was covered with ice. Then, rapidly for glaciers, the ice had retreated. First lichens appeared on the bare rocks, then other plants. Dryas was one of the pioneers, a delicate, puffy-seeded plant, blowing in the wind, blowing its seeds across the rocks and into the tiny pockets of newly formed silt and dried lichen. Alder sprouts contributed nitrogen to the land to nourish other plants. Finally, the spruces and hemlocks grew up to top the alder, and it disappeared, except in thickets along the shore.

I was walking though a young forest. None of the trees had matured enough to shed old branches or to drop of old age in the usual jumble of fallen giants. You could walk in this forest, softly stepping on the moss to kneel down and examine a mushroom. And now, at last, another of my voyage’s themes, the quest for edible fungi along the route, was coming to pass.

By the end of the first day at the campground, out on a beach log near the tent, were a dozen jars, cups, and cans, each covering a mushroom cap which was slowly dropping its spore print onto a sheet of paper in individualized patterns, with the colors to help in the identification. Soon I had six firmly named and rated as edible, good, or choice selections for dinner. Some were old friends, some new. One of the most easily identified and delicious was Dentinum repandum, with toothlike nodules instead of gills. Another was a vivid purple one, shaped like coral, but purple food seemed very strange. Still, bears made purple piles from blueberries …

No single mushroom reference book was adequate, and I used the park library to cross check, meeting there another new friend, Doris Howe, volunteer librarian and wife of the former park superintendent, Robert Howe.

Glacier Bay was a national park that lived up to all the writers’ superlatives. No way could you swing by the place while driving on a blurry vacation to include seven parks in six states in five days. You went to Glacier Bay on purpose, by plane and bus, by cruise ship, or by private boat. There were kayaks to rent within the park; a few people, like my friends, brought their own, but there probably weren’t more than 30 kayaks that year paddling into Glacier Bay Park from another area.

Meanwhile, the daily film showings, nature walks, and pamphlets from the desk in the lodge were answering the questions I’d been storing up for two months. The naturalists were knowledgeable, helpful, and delighted with their jobs.

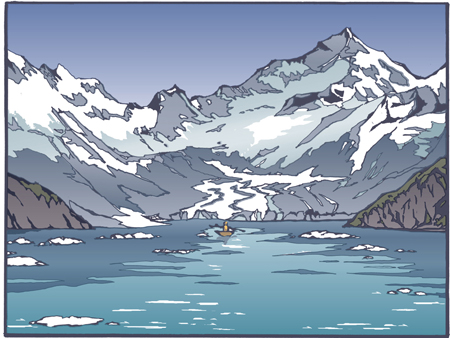

To see the glaciers, still melting in retreat, I would need to go up one of the arms of the bay. It would be 60 miles, six to eight days of bare cold country; there were as yet no forests up the bay. I mashed down the Scottish soul, bought a ticket for the daily cruise ship, and rose at six the next morning and dressed in all the layers of clothes I owned. We cruised up past the Beardslee Islands, past Strawberry Island, emerging from forested land into a barren country with its own stark beauty, like the lava fields of Hawai‘i. Mike Rivers, our onboard ranger-naturalist, explained what we were seeing. Then we moved in close to the Marble Islands. Birds! Pigeon guillemots, cormorants, common murres, murrelets, black oystercatchers, and who could help being delighted by the real thing from the poem:

“There once was a puffin shaped just like a muffin

Who lived on an island in the deep blue sea”

If you aren’t a bird-watcher when you come to Glacier Bay, you become one. Sea creatures had always seemed more enchanting than birds, but here the birds were sea animals. A sea otter had been my ideal reincarnation form, or perhaps a selchie, the mystical half human, half seal of the Outer Hebrides, but after Alaska that changed. Next time around I would be a loon or merganser, or a pigeon guillemot. They can all swim a long distance under water and fly.

Throughout the whole voyage I had been watching guillemots. When I came within 50 feet they would suddenly decide it was too close, paddle rapidly away, and then flap their wings, trying to get airborne. The red feet would keep paddling as they rose, beating the water in a frantic toe dance, like the hippopotamus en pointe in Disney’s classic film Fantasia.

The endearing marbled murrelet, with its single peep like a baby chick, was smaller, and usually dove to escape, but sometimes it flew off, the stubby little body hitting the water several times before it was aloft, like a child’s flat stone skipping on a pond. Now there is a whole book about the marbled murrelet, Rare Bird, by Maria Mudd-Ruth.

At Muir Point we dropped off 12 teenagers with six kayaks, then dropped and picked up more at Riggs Glacier. The cost of a drop-off was the same as a tour, $27. At Riggs, the captain turned off the engine, and we floated there in the silence, listening to the voice of the glacier, snapping and cracking and sometimes calving off a wall of ice, the birth of an iceberg. Because of its crystalline structure, the glacial ice absorbs all colors except blue, which it reflects. The passengers stood quietly on deck, rapt, awed. Near me a woman breathed, “Thank you, Lord.”

That was what we had come so far to see and feel. The faces were the same as those watching an eruption of lava in Volcano National Park in Hawai‘i. This wasn’t just a quiet piece of scenery. It was a living, breathing, birthing part of the earth.

In my tent that night I reread Dave Bohn’s Glacier Bay: the Land and the Silence. I envied him. The years that went into it, and the book that came out of the years, were more than enough to fulfill a lifetime: It doesn’t matter what he did before or after. A book like that justifies an author’s place on earth for 90 years.