13

Two days later and 10 miles east, I launched into the turbid Salmon River of the Gustavus glacial plain. Doris Howe watched, sitting quietly on the bank as I paddled down between the grass and mud shores toward the sea. The wind was rising with a steady light rain, my foul-weather jacket and pants were leaking, and that wind was from the southeast, its usual direction when I was heading southeast. What a beginning for the final week!

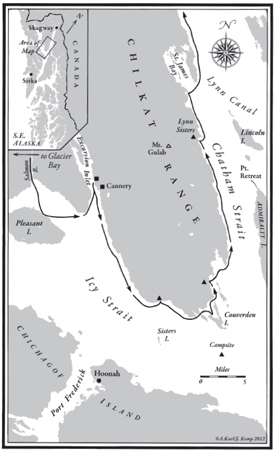

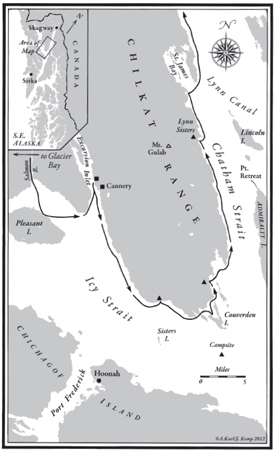

I tried lining the boat, walking on shore and towing it, but even a slow paddle was faster. There were mud flats ahead, so I crossed to Pleasant Island, named by John Muir and the missionary Hall Young in 1879. Lunch was a granola bar and a new batch of smoked salmon from Ann and Jim Mackovyak of Gustavus, another pioneer couple with the independent lifestyle that Alaskans treasure. After a few miles along the lee shore of the island, I headed out again into Icy Strait and east to the long peninsula, looking now for campsites, but all were rocky and none was flat.

Excursion Inlet ahead was supposed to have a good store. What else was up there, and why hadn’t I researched it? Through the rain I paddled toward the lights, which slowly enlarged into a cold storage plant with people up on the pier busily loading fish. Farther on was a small-boat dock; there I unpacked the bags and lifted the boat onto the float, as the surge was too strong to leave it bouncing and rubbing the dock.

Don McLean, the night watchman, kindly gave me use of a dormitory that was being built for the cold storage and cannery workers. His cheese omelet at breakfast demonstrated his wintertime profession of cook. My voyage from Ketchikan didn’t mean much to him, nor the destination of Skagway, as he’d flown to Alaska from Seattle and didn’t know the distances, but he understood that I’d been traveling since June and thought I’d gone about 700 miles so far.

At the store I bought a few supplies and loaded up. It was easy paddling, with the wind down from yesterday and a thin sun through the drizzle. This was a well-known fishing ground called the Home Shore, and many boats were out, the small hand trollers designated by H.T. lettered on the side. They had a cheaper license, fewer regulations, and the winches were cranked by hand, not power. Maybe my boat ought finally to be christened, if not Kaymaid or Selchie, then perhaps the H.T. Puffer.

The route was north, but I had to go south first, down to the end of the peninsula, then east to Lynn Canal. Out three miles to the right was the Sisters Island light. Hour by hour I moved around the curve, moving that light toward my stern. Already it was time to find a camp; the days were getting shorter. The next landing beach had a Forest Service sign, “Bald Eagle Nest Tree,” but neither eagles nor nest were aloft. Fine, I wasn’t about to camp under either one. A cabin had been here long before, with old boards and a rusty washbasin the only remnants.

Dinner was going to be a celebration. Once around the tip of the peninsula tomorrow, I’d be in Lynn Canal, the final waterway to the final goal of Skagway. No more resupplies. This was it, the last lap.

I pulled out the bag of ingredients for beef hekka, mailed from Hawai‘i by my cosmopolitan friend Trixie. The strings of dried gourd were six feet long, but I soaked them, and then, in an improbable maneuver, tied them in a series of overhand knots and cut between them. The freeze-dried pieces of tofu had the flavor and consistency of small sponges, so I scattered them for the squirrels, but ate the good stewed gourd, sauce, and shiitake mushrooms.

Why such an emphasis on food throughout this trip? There were few physical pleasures – rarely any clean clothes, seldom any warmth of sun, firelight, or a bath, and no time to build any warm human communication. Food was pleasurable to the taste, provided sheer warmth in the belly, and had the satisfaction of a creative art form, the craft of cuisine. There was also the half-spoof goal of the gourmet kitchen, and the real need of the body for fuel to power the 48,000 pounds of water moved in paddling each day.

I could have foraged more. David J. Cooper, in his book Brooks Range Passage, describes gathering much of his food from plants as he walked the 120 miles to the Arrigetch Peaks. But only a limited variety of plants grew on shore here, and I needed the time for traveling, not foraging. Sometimes during the long hours of steady paddling I envisioned a different kind of trip. No gadgets or plastic bagged meals. My three-pound tent was adequate to keep bugs out, but the Gore-Tex fabric, once clogged with salt air, no longer shed water, and I had to rig the tarp over it each night. The open tarp keeps the rain off, but the air that blows under is so heavy with water and salt that nothing stays dry unless I leave it bagged. I would design a new tent myself, large enough to stand in, with walls. I think I could design and build a tiny portable woodstove also, as I had a fireplace for the VW bus in Europe years ago. Take fishing gear, a Bic lighter not matches, an old pot, a saw, coffee, a skillet and grate, and a kayak of longer, lower proportions.

I would have no schedules, avoid towns and people. Use more outside routes; take one island, Baranof or Kuiu, and go around it, into every bay. Listen and look and smell until I forgot the body and felt like just another animal, wary but capable of living in this country, the senses alert, the animal instincts reborn.

Doing what you want to do isn’t a question of can you or can’t you, yes or no, but deciding what your ultimate desire and capability is and then figuring out the steps to accomplishment. It’s “I’m going to. Now how? What gear will I need? What skills will I need? What will it cost? When will it happen? When I succeed, what next?”

Coming back to the present, I used the rusty washbasin as a base for a wood fire and warmed the clammy sleeping bag, while heating hot sake. Not for me a thimblesize sake cup. The quarter-cup of rice wine could be heated directly over the flame in my two-cup enameled mug, which was large enough to cover my nose while I sipped, sending the pungent hot fumes up my nostrils while the hot wine went down my throat: double-duty value.

September 1. More mushrooms had popped up overnight from the autumn season and the rain. In the usual two hours I was under way. At home, where I know precisely where everything is, I can lay out clothes and a thermos of coffee the night before and fix a blender breakfast in the morning. Not here, where I unbuild the house first.

At least the packing was now a well-rehearsed ballet: The tide is incoming, so estimate the distance it will rise up the beach. Carry the small items and the four large bags down to the staging area, about 20 feet from the water. Try to lay them on seaweed or on bare rock so they won’t adhere to sandy gravel and drop it in the boat. Untie the boat from its forest mooring, carry it down, and lay it with just the bow in the water. Loop the lifeline over a rock. Stuff the wine bottle – if one has lasted this long – into its cool cellar in the bow. Put the water bag on top of it, then the foot pump. The boat needed as much weight as possible in the bow and stern to offset the sag of my weight in the center.

All this I do straddling the boat and facing shore, with the water calf-deep on my boots. That way I can pull all the gear firmly toward me under the bow spray cover. Then I lay in the heavy blue waterproof bag, which contains the library, tools, clothing, and kitchen. Tuck the day’s water bottle just behind the inflated seat cushion. Snaphook the clear plastic chart holder to a side loop and lay it on top of the blue bag. By now, the water is amidships.

Straddling the stern, I load in the tapered plastic kayak bag, which holds lunches and dinners, carefully tucking it back over the boat’s air valves so as not to get a sudden whoosh of deflation. Pick up the fourth bag, which contains tent, tarp, air mattress, and sleeping bag. Snaphook one end of a line to its bottom grommet and the other end to a spray-cover lacing. That fourth bag is my treasured black rubber Navy bag, which also serves as a backrest.

Put on the yellow, bibbed foul-weather pants. Lay the yellow jacket on top of the black bag if it’s not raining. If it is, I’ll already be wearing both, put on just before I derigged the overhead tarp. Loop the strap of the camera over my head and under my right arm. Now the boat is afloat. Lay the paddle crosswise on top of the chart bag. Check to see that the paddle line is hooked to the boat, as I left it last night. The paddle will float, but with no spare, I can’t afford to lose it. Unhook the lifeline from the rock and loop it over my head and under my left arm. Move the boat out to an eight-inch depth. Get in and paddle out, watching carefully for submerged rocks.

Someday I’ll manage to do it all just that neatly, instead of having an outgoing tide leave the boat stranded aground just as I’ve got it all packed, so that I have to unpack and start again. You don’t drag these fragile craft.

I moved out past the boats that were fishing in an oval pattern along the coast. My chart was a large-scale one that stopped out in midchannel, but somewhere across Icy Strait, in the pale outline of land that I could see, was the town of Hoonah.

I paddled past a “cabin” on the topo map. No sign of it. On to a reef point covered with the silver gray of gulls. They eyed me warily, then lifted off like a feathered flying carpet, leaving only the barren rocks. I cleared Ainsley Island to my right, then paddled on into a tide race at the north tip of an islet. Powering through and landing, I searched for a camp, but all sites were miserably wet and rocky. The only asset was a bed of beach asparagus to pick for dinner, but I wasn’t looking for delicacies, only necessities. A camp or cabin was rumored to be in the bight of Couverden Island, so I paddled down against the wind and rain, but found only bog. Under the alders I sat on a wet rock, visor dripping, and lunched on crackers, tuna, and Tang.

One hundred and two years earlier, John Muir, Hall Young, and a group of Indians had paddled through this area, also en route from Glacier Bay up Lynn Canal. Even when wet and cold during his travels, Muir was using such phrases as “the wind made wild melody,” “the shining weather in the midst of rain,” and “the glad rejoicing storm in glorious voice was singing through the woods, noble compensation for mere body discomfort.” As I hunkered down, glum, soggy, and disconsolate, I thought of Muir’s writing, then suddenly exploded with laughter, spewing wet cracker crumbs onto the yellow pants. Muir had made his voyages between 1879 and 1899, but it was not until 1914 that he wrote his journals into the book Travels in Alaska. The previous spring I had obsessed over the beauty of this country. Already forgotten was the memory of what bloody hard work a short expedition had been only the summer before. Possibly even the great Muir, who had often gone into the wilderness with only a blanket and a crust of bread, had forgotten some of the misery as he wrote his book 15 years later in front of a fireplace in California.

Heartened, I paddled out of the bight. A powerboat, the Tiller Tramp, chartered for fishing out of Juneau, came in from what they described as a “rough channel” and anchored. I paddled out from the quiet shelter of the tip of Couverden into Lynn Canal, the water under my elbow changing in 10 strokes from calm blue bay to a steep, sloppy green sea with a south wind of 25 knots. I looked south, upwind, judged the seas, figured the boat could handle them, and headed north, seas breaking around the boat as it slid down the face of the waves. This boat had no rudder, but with its rocker bottom, like a white-water kayak’s, it was responsive instantly to a pull, a brace, or a backwater stroke. We slewed and skidded and raced along, just far enough to see the long coastline to the north, then came ashore.

I shoved through the thick alder and tangled shore brush into a young spruce forest. The only spot that was flat and clear enough to pitch a tent was in the middle of a small path. There were no bear-crap piles or tracks. It looked like a mink or deer trail. It was getting dark at nine o’clock these evenings, especially in a dark forest like this. Still raining.

After rigging three corners for the tarp, I looked for an overhead branch to toss a line over to pull the center loop into a four-sided roof. In the dim light one looked suitable. I tied a rock to the end of a line, threw it up and over the branch, knotted the other end to the tarp loop and hauled. The branch bent down and released a huge dead treetop that had fallen and snagged on the branch. It hurtled past my shoulder and crashed on the side of the tarp, puncturing it with a jagged limb and snapping one corner line. Loggers call them widow makers, justifiably.

I cleared the debris, taped the tarp, rerigged the lines, and made a fast dinner by candlelight.

September 2. I was fixing breakfast and heard a squirrel chatter. Like a small kid trying to pull a big beach umbrella, she was dragging a giant mushroom by the stem, until it broke off. Undaunted, she grabbed one edge in her teeth, ran forward, looking to me like a small Ubangi bulldozer with the mushroom as her lip disk, and disappeared with her prize. (Later I read an article that said it wasn’t the Ubangi, but the African Sara and also South American Suya, who wore lip disks; I often think that half our information is misinformation.)

Half an hour later I had the tarp down and was derigging the tent, standing sideways on the trail. A dark shape came up over the rise to the north. I gasped in surprise, gave an ohh of appreciation, and froze. The black wolf came loping home from the morning hunt, tongue swinging, alert, assured. I straightened, skin prickling in a primitive reaction. His glance took me in with instant comprehension of all that I represented. His fluid pace did not slacken nor his paws miss a step, but he veered off the trail, through the forest, and was gone. The camera was hanging on a tree. I stepped toward it, then dropped my hand.

Like the encounter with the orca, this was a treasure to hold in my mind, forever to recall with gratitude. I had always thought of wolves as gray and the size of a German shepherd. This one was black and the size of a Great Dane. I had read David Mech and Lois Crisler, and later I would read Of Wolves and Men, by Barry Lopez. “Many people in Alaska,” he wrote, “hunters, biologists, native people – volunteered the information that the biggest wolves they’d seen were blacks.” And: “Here is an animal capable of killing a man, an animal of legendary endurance and spirit, an animal that embodies marvelous integration with its environment. This is exactly what the frustrated modern hunter would like: the noble qualities imagined; a sense of fitting into the world. The hunter wants to be the wolf.”

I wasn’t and I didn’t, but I felt akin to the wolf. It seemed somehow as if we recognized each other in that brief meeting, acknowledged each other without fear as solo animals of different breeds, and went our separate ways. We weren’t communicating in human words, but in the tone of voice, gesture, stance, scent, and movement. Was all this a part of some system of interspecies awareness? As much as anything else on this voyage, I wanted that sense of fitting in, coexisting with the animal world.

Two years later I read in a newspaper item that in Alaska the mass killing of wolves from airplanes and helicopters had been approved “in order to save an adequate number of moose.” An adequate number for the hunters. I knew it was supposed to be part of a carefully researched plan to maintain populations of animals, but the methods were hard to accept. Maintain which populations for whom?

Mussels Neapolitan

1 cup of dry pasta

3 large or 15 small mussels

¼ cup olive oil

3 cloves garlic, minced

¼ teaspoon hot pepper flakes

4 to 6 dried sliced tomatoes

½ cup dry white wine

2 cans rolled anchovies with capers parsley or wild greens

Cook pasta and drain. Steam mussels and remove from shells. Save water. Heat oil. Add garlic, cook briefly. Add pepper flakes, tomatoes, wine, and ½ cup mussel water. Cover and cook 10 minutes. Add anchovies, capers, and parsley. Add mussels. Heat only to boiling. Serve over pasta.