14

Looking out from the shelter of the small offshore islands I saw the seas had gone down overnight – down to four feet – but still big enough to demand attention to each wave. I angled over to Point Howard and kept going four more hours. Rain and a tailwind. There was supposed to be a float house in a cove opposite Point Retreat, but when I arrived at low tide, no house, so I tied up and walked into the estuary, then around a curve to a large boggy area. No buildings were in sight, but float house locations are designed to be temporary.

Six miles later I stopped to fill the water bag. It was a good campsite, but there were dozens of salmon swimming upstream, half-eaten ones on the bank, and a pile of bear crap every 20 feet. Go! As I launched from shore, one paddle blade snapped off at the shaft. Was it already cracked from the strain of 80 days under way? Had I hit a rock underwater without knowing it? The broken blade was floating, and I grabbed it. Using one paddle and the old canoeing J stroke, I moved along the shore to a curving beach a quarter mile from the stream. At the end of the beach was a rock cliff. Around it I would be out of the bay, but out into rough water again. With one paddle? Not advisable.

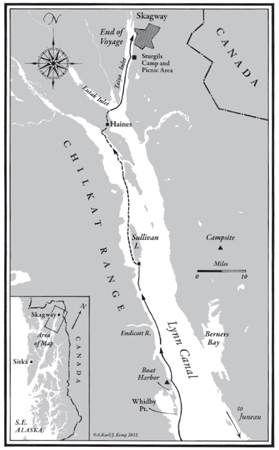

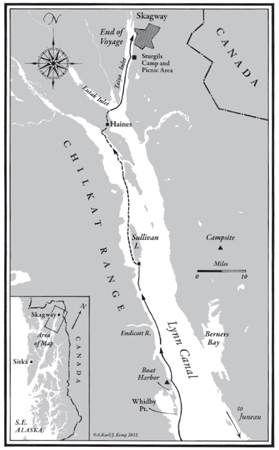

I set up camp, confident that I’d be able to repair the broken paddle, but I needed daylight for the precise careful work if I were not to botch the whole job irredeemably. I couldn’t rely on anyone else. I had seen no boats all day, up and down the 40 visible miles of Lynn Canal.

All three pairs of socks were wet, so I wrapped my feet in a pair of wool underwear and wore the spare longies to bed. I was also wearing the wool cap that my sister, Marge, had knitted. A professor of home economics, she was mostly concerned with the administration of a department and with the training of graduate students. Unlike some academic types, she also practiced the skills of carpentry, architectural design, good cooking, and knitting wool caps. On the whole trip, that cap had been the single most useful item. It was my thermostat. Body too warm? Take off my cap. Feet cold? Put on the cap. Fifty percent of a body’s heat can be lost through a bare head. I wore it every night, and could therefore use a lighter-weight sleeping bag.

The tarp was overhead, the tent was zipped up, the wool pants and the pile suit were under and over the air mattress for insulation. That Stebco three-quarter-length mattress deserved a citation. It had been left at my house 10 years before by an unknown guest, and since then it had been my bed on coral, on lava, on twigs, and it still endured. It made all the difference between a good night’s sleep and mere survival. When it finally wore out, five years later, I could find no comparable lightweight product. Soon after, Cascade Designs had invented the Therm-a-Rest mattress, not the soft comfort of an air mattress, but better insulation.

Propped on my elbows, I looked through the tent screen. Across the channel, Herbert Glacier flowed ponderously down the slope, and the sky was almost clear. On my side of Lynn Canal, Mt. Gulab rose starkly bare above the curve of the beach. I stood looking at it for a long time as it grew dark, watching also for any movement of bears back at the stream across the bay. No tracks were on the sandy beach here. Nineteen miles today; I needed sleep.

The sun rose at 6:00 am. Sunshine – for the moment. I took my mug of coffee out to the beach to see the mountain better. At my feet was something else. A bear’s pawprint, seven inches across. Indented in the sand was a paw path, coming toward the tent, then turning toward the sea and back toward the stream. It did not seem from the tracks that this bear had come closer than 50 feet, and it was reassuring to think that they had a set distance. Perhaps she had been curious, had not smelled food as mine was dried and sealed airand watertight, and had decided that I was female without cubs and therefore not a threat. So she had not needed to be fearful or aggressive, and had gone back about the bear business of catching fish upstream in the shallows. So far, the coexistence theory was working.

Oatmeal for fortitude, and time now to tackle the paddle. I unscrewed the broken stub, pulled it off the aluminum shaft, and put it away. It was surplus now, but that stub of plastic might have a use. I examined the broken blade, and dug out the foam that had kept it floating yesterday. At the base of the foam core was an inner ridge of hard plastic that stopped the end of the shaft at its original depth. OK, I’d have to either make the shaft smaller or the blade hole larger to reconnect the two. I could try heating the end of the metal shaft on the stove and ramming it into the hole to melt the plastic ridge. I refueled the stove, put on a glove as a pot holder, and carefully heated the shaft, then quickly rammed it into the blade, turning as I shoved it down. I could melt and ream out an eighth of an inch at a time, then pull the shaft out, scrape the melted edge with the knife blade, and reheat the shaft. I got about two inches done of the four inches needed. On the last insertion, I didn’t keep turning it fast enough, and it stuck. I tried heating the shaft and pulling. I tried holding the shaft and pushing with both feet on the shoulders of the blade. It was firmly stuck. Fine. If it’s really going to stay there, I’ve achieved the objective.

I took the paddle down to the water’s edge and stroked it hard back and forth in the cold sea. Would the coldness contract the sections so that it would come apart? It did not. A month later, at home in Hawai‘i, I lifted the paddle off its wall hooks, and the blade fell off. Sometimes you are certain that your gear has a brain and soul of its own.

All the time I was working, a corner of my mind was still wrestling with bears. This was to be the last pawprint, the closest I would come to actually seeing a grizzly on this voyage. All of the concern and worry, all of the snapping twigs, all of the evidence, and yet not even a distant sighting of one.

A death or two and several maulings do occur each year in Alaska, but it was not until two years later that I had a close meeting. I was to camp at an old cabin in Holkham Bay, 50 miles south of Juneau, en route to the fjord known as Fords Terror. I took my pot of pasta outside and sat there, reading and watching the turquoise icebergs float across the seas. My journal records the episode:

There was no sound, no twig snapped, but I turned and looked over my shoulder. A grizzly bear was standing on the path, 18 feet away, looking at me with golden eyes. It wasn’t a big bear, perhaps only 400 or 500 pounds. I stood up slowly. Don’t run from a bear – they run 30 miles an hour. Why scream – no one will hear you. Don’t startle this bear. Try a quiet conversation.

The usual rapid-fire words were slow and precise.

“How come you’re so close? The literature says bears stop at 75 feet, turn sideways and pose to show you how big they are. You’re messing up the literature, and do you mind if I come two steps closer to get my camera hanging by the door? I’ll need a photo of what ate me.”

She looked at me calmly, then turned around, moving stiffly and precisely as if she, too, was uncertain in this situation. At the click of the camera she glanced back, I snapped a second photo then she padded slowly away on the trail through the bushes. She didn’t seem aggressive, just visiting and checking to see who was in her territory.

Three days later I would return from Fords Terror, unpack, and walk that trail to the stream. I had thoroughly established my scent on that path four days ago. Now, walking the trail, I sang loudly.

“The bear went over the mountain, the bear … ”

I stopped. There was a large bear pile on the path, precisely erasing my spot, thoroughly reestablishing her territory.

Two-thirty in the afternoon I was having lunch, inside the cabin this time. The doorknob rattled and turned, five feet from my table. I could see her head through the thin plastic sheet on the door, holding the knob in her teeth and turning it. I snatched the camera and took photos, talking all the while.

“Really, this is too much. No, I’m not going to open the door and invite you in. Tomorrow I’ll be leaving and the territory will be all yours again. Now go away.”

She turned and ambled off down the beach.

I had expected her head to butt clean through the plastic sheet, and later included a huge bear-face photo like that in slide shows.

But now, on this first voyage, with only the rueful awareness that the bears knew me pretty well and I didn’t know them at all, I packed and launched with the incoming tide, out around the rock cliffs named the Lynn Sisters. Farther south, down in Frederick Sound, are The Brothers. As always, I wondered what the Indian names for all these places were, and that led me to wondering what the name for the inhabitants of the Americas would have been if Columbus had not believed that he had reached an outlying island of India.

Did John Cabot, looking for a route to Mecca, call them Indians? Cabot himself was an Italian, Giovanni Caboto of Genoa, who moved to London and was commissioned by Henry VII to explore “the islands west of Ireland.” What did the Vikings call them? Did St. Brendan of Ireland have a name for the people he found in the New World? There should be some better name for the native peoples of the Americas. DEAP, Descendants of Early Aboriginal Peoples, seems unlikely to come into popular usage. Inuit means simply “the People.” “Americans” has been assumed by the residents of the United States of America, but there are also the United States of Brazil and the United States of Mexico. It seems doubtful that we shall ever achieve the United States of the World.

Musing, I kept paddling, and the sun kept shining. Around Whidby Point I stopped and spread out the sleeping bag, tent, and tarp to dry. The wool socks were laid out too, but they would take longer. Impregnated with saltwater, they’d need to first be thoroughly rinsed with freshwater. By the time I got to a stream again, there would probably be no sunshine.

The tide had turned and was now moving strongly against me. It took three hours to paddle the four miles to Boat Harbor. There was supposed to be a beach a mile beyond it. The harbor itself looked good on the topo, but the entrance was narrow, half the width of the slot into the bay of Hole in the Wall, near Point Baker, and the tide was racing out like rapids in a river.

At 8:30 pm the sun had set, and it was getting dark. Now, in September, there were no more long twilights. I made a small bet that within 20 minutes of landing at the beach ahead, I would have the gear and the boat carried up to a flat area and would be sipping hot soup. I won the bet, had the kitchen laid out on a long chunk of 12 by 12 timber, had a small log to sit on and a branch wedged upright to hold the water bag. Those wine-box bags were wonderfully adaptable; the bag that held my water had an ingenious one-hand spigot; the one I used for a seat was filled with air instead of water, and its aluminized surface reflected my body heat. If I’d had a crab trap, I’d have used a spare bag as a buoy for the line. Two of them laced together could make a float to stick one end of my paddle into; the other end, atop the boat, forming an outrigger to steady the boat for reentry in case of capsize. A float with a hook might hold your bathing suit while you skinny-dipped – a dissertation could be written on the use of wine-box bags.

The tent and tarp went up while dinner cooked. When the full moon rose over the mountain ridge across Lynn Canal, I took a timed photo. It had been an eventful two days. Widow maker, bulldozer squirrel, wolf, bears, a broken and mended paddle, sunshine, and now a moonrise for the first time in a month of clouded skies.

Being alone was still satisfying. After so many years of jobs and children, not coping every day with dozens of problems was a luxury. Space to think. May Sarton has said, “With another human being present, vision becomes double vision, inevitably. We are busy wondering, what does my companion see or think of this, and what do I think of it? The original impact gets lost or diffused.” The concept of meditation recognized the need; if you couldn’t be physically isolated, you could try for a mental space. Americans are said to have a love affair with automobiles, but it may be only their need for solitude, if one of those enclosed boxes is the only place they can achieve it. There has to be some time when the brain can synapse the ideas already there into lateral and diagonal connections without constant new bombardment.

“But are you safe alone?” people ask. I’m certain that I am safer.

Safety is more good judgment than reliance on people. Each day as I packed I kept going through the what-ifs, and preparing for them. “When in doubt, don’t” was a good rule. Alone, I could meticulously prepare for launching, checking how and where to stow each item, keeping the emergency gear at hand. No one rushed or distracted me. Nothing except tide or wind timed the departure or told me what to do. I didn’t have to risk my life rescuing someone else. On earlier group expeditions I had loaned critical gear because people neglected to bring their own. They snapped my knife blade, left my books and charts in the rain, burned the nozzle off my foot pump using it as a fire bellows, and sliced my boat dragging it out of their way. Animals were less dangerous than humans.

“But aren’t you afraid alone?” Of what? Fear is of the unknown. I had almost learned what the boat, the gear, and the body could do. Even the sea and the weather followed patterns. I was still learning, but all the percentage figures said I was safer here than in a city or on a highway.

In a few days the voyage would be over. What would be next? Before I left home I had rewritten the lists: income and outgo for the next five years, 25 things I really wanted to do, how much they would cost, and their priorities on a one to five scale. What was the five-year plan, the 25-year plan? How much time could I reasonably expect to have before physical deterioration set in? When I was five years old, the time-was-there-was-time palindrome of endless years stretched ahead. One year was a big 20 percent of my whole life, so a year was a very long time. By the time I was 30, the ratio had shrunk. One thirtieth of my life was a very short time, and it whizzed past.

What were the main issues I believed in, the big problems the world faced? By now I didn’t believe the world was getting better, only more complicated and less likely to survive. Still, we all need to go down fighting, lost cause or not, backs against the wall. The biggest issue seemed to me to be overpopulation. OK, go home and enlist in the battles. I was an unlikely Cyrano or Don Quixote, and there were many truly valiant and capable people doing battle.

Age was also relative. At 29 you say 30 isn’t old, but 40 is. At 59 you say 60 isn’t old, but 70 is. At 89, a lovely friend is saving for her old age. Some mornings after I’ve been in the ocean in Hawai‘i, I feel 14, and when I glance in a mirror I stop, stunned. “Who is that?”

Part sun, part cloud, a little rain, and the vast empty channel with its high snowcapped ridge of peaks on the far side. On my side I was too close in to see beyond the first slope up to the high spine of mountains that I knew was there from the maps. Ahead was Danger Point, and as I paddled close I could understand the name. A ledge jutted far out into the channel, just under the water for much of the tidal range, just deep enough to be unseen, and shallow enough to tear the bottom out of a boat. It was good mussel habitat, though, the crust of shells so thick I couldn’t see the rock. I nudged up to the opalescent, deep-blue wall that towered over my head on this low tide, estimated that it would be three feet under at high tide, and backed away from the sharp lips of the shells.

Ahead was the Endicott River and a tidal flat, a fan-shaped delta of gravel and rocks brought down by the flows of centuries. I had planned to stop at four o’clock, when the tide would turn against me, but by three a southeast wind was blowing enough to offset the tide. It was 10 more miles to Sullivan Island and a reported house. In another hour I’d be able to see the shape, far ahead. The tailwind was 15 knots, the seas only three feet, and the rain was light, so I kept moving. I was using painkillers every day now, knowing that I might be doing permanent damage to muscles and tendons, knowing also the recuperative power of this body, trading off the possibility of damage against the desire to reach the goal of Skagway.

I passed Sullivan River, but the freshwater was far upstream. The house ahead looked big and elegant. Would it be a summer home for residents of Haines or Juneau, all furnished and bolted against stray paddlers? Only as I made a backwater stroke and glided to a halt at the shore could I see that the windows were gone and that it was only the shell of a very old building.

I carried up the first load, set it down outside, and walked quietly into the presence of all the adults and children who had once lived there. Peeling wallpaper in the bathroom revealed newspapers and comic strips of the 1920s. It was like the house where I lived when I was five, near the railroad station in Zelzah, now Northridge, in southern California. This one, too, had a fireplace, a pantry, and a wide stairway up to bedrooms on the top floor. I set up my kitchen here on a similar second-story sun porch, then walked again through the house with a pot of pasta primavera in hand, listening to the remembrance of things past. At the foot of the stairs I paused, seeing in my mind a pool of blood. Weak from kidney disease, my father had crashed backward, hitting his head on the bottom step in that childhood house. After his death we moved away, but the plan of the house, the fig tree with sheltering branches to the ground making a leaf-walled playhouse for a small girl, Papa milking the cow in the barn, the pines of the mountains where we spent the summers – the images were forever implanted.

I rigged the tarp outside in a ground hollow to catch rainwater, put the sleeping bag and mattress in the back pantry, where there was the least wind blowing through, and wrote the journal for the day. My hand was tingling and numb; a paddling callus inside the thumb gripped the pen. The dirt under the fingernails was Alaska dirt, and I was already homesick for each campsite of the voyage.

Twenty miles north and a day later in the town of Haines, the radio forecast was for a 25-knot northerly wind. It sounded like the onset of winter, the beginning of the noted storms of Skagway, coming down from the Arctic through the Yukon territory and funneling down the valley through Skagway into Lynn Canal. Today I had planned to paddle the final 17 miles. Could I get to Skagway ahead of the storm? There were no landings, no beaches along this last gorge. Weather forecasts were usually accurate as to content. Only the time of arrival of the wind and rain varied from the reports. If I couldn’t make it into a northerly wind, at least I could turn and come back downwind.

I headed out and across Lutak Inlet, then around the point. No outlets were ahead, no straits, no exits, only land up there at the end of Taiya Inlet, the northeast final arm of Lynn Canal. There was a 10-knot northerly headwind and an outgoing tide the first hour, then a gradual tide change. I crossed the mile over to the east side in the steady rain. There were no landings for going ashore, just steep rock walls. Only once did I find a rock low enough so that I could climb out for a pit stop. Steady paddling. Lunch of a granola bar, a mint patty, and an orange I found floating. The boat had two quarts of water in it from the rain, but there was no place now to stop and unload to turn it over and empty it. I sopped up what I could with the sponge and squeezed it overboard.

The ferry Columbia passed me, heading south. I was fearful of the wake, but she was out in midchannel, her waves only two feet high, and not steep or breaking at this distance of half a mile. I had run off my last chart, but figured where I was on the topo map from the shape of the waterfalls and the angles of their steep courses down the cliffs.

I kept watching ahead through the rain, counting ridges. There were at least three to pass, plus a doubtful one that might be the last toe between Skagway and the old town of Dyea where the Chilkoot Trail of the 1898 gold rush began. Knowing the total distance, I figured I should be in Skagway by 6:00 pm. Finally a small boat ahead turned right and disappeared in front of the last ridge. I knew now. There was only an hour left of the voyage.

To my right were a cleft, a stream, and the familiar brown and yellow carved wooden sign of the Forest Service. I came ashore on the rocks. Sturgils Camp and Picnic Area, the lettering said. A trail wound inland, and heavy wooden tables were set up on a small flat with a view down the inlet. I went back to the boat and pulled out from the bow the wine that I bought the previous night in Haines. I climbed back up to the tables, uncorked the bottle, held it out in salute to Lynn Canal, then drank a toast to that one view and to all the memorable views I had seen. I toasted the whole voyage, the rain, Alaska, the dark forests, all the animals I had met and all the ones I hadn’t, the sea, and finally:

“To Aud. You did OK.”

The rain eased into a mist. The mountains were clear. Each needle, each scent, each pebble was sharp and singular. Across the inlet a glacier spilled over a high ridge, its crevasses an electric blue. I recorked the bottle, mist and tears and wine dripping off my chin, then went back to the boat and paddled on. The wind had shifted. On this last mile I would have a tailwind, a final gift from the sea.

I rounded the last point. A warehouse was ahead, then the huge bulky stern of a cruise ship. Only a few passengers were on deck in their raincoats, slouch hats, and plastic bonnets. They scarcely glanced down at my boat and its soggy 60-year-old paddler. Adventure was only relative. The ship was theirs, this boat was mine, and I would not trade. I slowed the stroke, savoring, and paddled on into the small boat harbor. Then, barely moving, I stroked around the cemented dock, past the moored skiffs, and glided to a stop at the foot of the shore ramp.

I put the paddle up on the dock, then a knee, and rolled out. I unclipped the lifeline, used it to tie the boat to a cleat, and looked around, north toward the Arctic, up at the mountains. The first snow of winter was on the slopes, the alders were turning gold, the last flowers of the fireweed were at the top of the stalk, and the journey was over. I pulled out the half bottle, uncorked it and looked down at the yellow boat. Eighty-five days, 850 miles.

I poured the last of the wine over the bow.

“Well done, small boat.”