8

DEVILS ELBOW TO BARANOF ISLAND

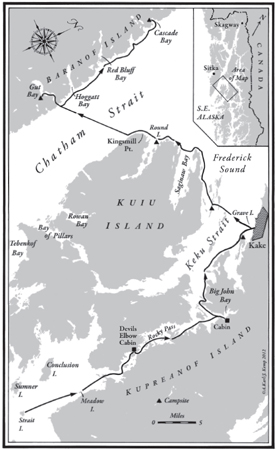

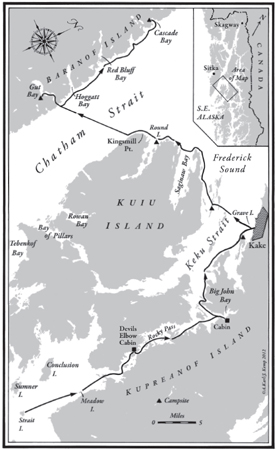

It all worked. At 10 am, I shoved off from Strait Island and in three hours was even with Conclusion Island, where Vancouver completed his northward exploration in 1793, then went back to winter in Hawai‘i before returning here the following year. Later I read Vancouver’s own journal notes about this area:

“On leaving the vessels their [two small rowboats’] route was directed toward Conclusion Island, passing in their way thither, a smaller island that lies nearly in the same direction from Point Baker, distant about four miles. This island is low, and is about a mile long in a north and south direction, with a ledge of very dangerous rocks extending from its south point.”

Agreed, Captain Vancouver. I should have read you first.

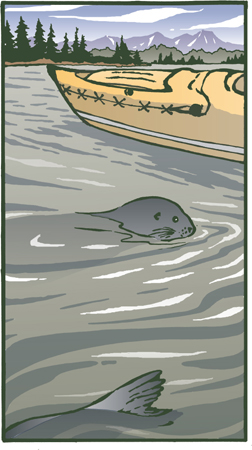

It was raining, and seals sat on every rock, catching their rest before the high tide covered their perch. A southeast wind made steering more difficult, but at least it wasn’t a headwind. During lunch at Meadow Island, I checked the chart, and then headed up past Skiff Island and through a maze of rocks. The seals were keeping up with me for a time, so I sang to them, “I love to go a-paddling, along the ocean track.” Each time they surfaced they were nearer, keeping pace only a few yards away, but finally they dropped behind.

A 20-knot wind blew steadily from astern the last two miles. I searched the shore for any sign of the cabin, then rounded an islet and saw the roof of the Forest Service A-frame ahead, right on the narrow isthmus. The Devils Elbow itself, a right-angled narrow tidal pass of roaring rapids, was a mile off to the east. With my shallow draft I had bypassed it via this other route past the cabin.

I landed on the mud just below the grass and began carrying up the first load. Suddenly I was on the edge of a deep pit of fire, 10 feet wide and nearly to the cabin, charring and sparking through the soil, eating back under the turf where it was sheltered from the rain. I spent the next hour carrying seawater to douse it, then stood knee-deep in the wet ashes to throw more buckets of water back under the ledges. Like the peat of Ireland, this is organic soil, the forerunner of coal, and it can burn underground in all directions if a fire is not thoroughly extinguished. Inside the cabin was a small can of apple juice, open and moldy. There were boot prints in the mud and an entry in the cabin’s log from 10 days before. The visitors had probably started the fire to burn trash. In a few more hours it would have burned down the cabin.

I woke early to a gray and rainy day. The oil stove wasn’t operating, though there was plenty of fuel. Using my vise grips, wrench, and knife, I worked on it for an hour. The line seemed to be clogged between the carburetor and stove intake, and I couldn’t get that section apart. I kept lighting a bit of oil in the stove sump, hoping to dry some clothing still wet from yesterday. I could cook on my small camp stove, but I couldn’t warm the cabin with it.

Five more days to the resupply at Kake, where I would need to pare down to the minimum of gear before the next section. That one would be the longest without resupply, and I would also be carrying a pack frame for the planned portage at Catherine Island. My schedule said 16 nights, but it didn’t allow for wind, or for resting up after rough days, or for enjoying good new places. I needed to plan on 20 or more. No cabins would be on that leg. The only part of the next three weeks I dreaded was crossing Chatham Strait, 12 miles wide.

So far, the trip had seemed to be more labor and pain and problems than good times. I’d said that five bad days to one good one was a tolerable ratio, but it felt as if it had been ten to one. Four days alone now, and I was standing at the window staring out at the rain wishing for company. I pushed my chin up with one thumb, and went back to evaluating what to send home from Kake. I was remembering that chin-up gesture from a long time back, back to the early days after the divorce: four children, and calluses under the chin.

Hah! I knew what was wrong. I couldn’t lay a fire for the next visitor – no wood stove.

In the morning I packed and carried the four loads of boat and gear, plus two spare garbage bags of empty bottles and cans, through hideous, sucking mud up over my boots. Kayakers should leave here at very high tide, or else from the east side of the north cove, where the rocks extend to the water.

In a steady rain, I launched my garbage scow and paddled out to the deepest water I could find on the chart, then sank the cans and bottles, one by one. It’s the best system I can figure. Burying doesn’t work, as some animal always digs them up. At sea, they’re out of sight, and burning the cans first, down on the tidal flat, destroys some of the coating so they’ll rust faster in saltwater. My diver friends have agreed with burial at sea, but only if I sink it all 40 fathoms deep, beyond the depth a diver can reach.

I headed north up the pass. It’s Keku Strait on the chart, but the local name is Rocky Pass, and for good reason. Buoys or markers were frequent, showing where a boat must turn to avoid a shoal or rocky ledge. The tide was not a problem, and paddling seemed to go so much faster when there was a goal each quarter or half mile.

A year later, all the markers would be gone. The budget of the Coast Guard would be cut, so they would evaluate all the sea routes in Alaska, knowing that not all of the aids to navigation could be maintained and that without maintenance, buoys would drift, lights would go out, and mariners would have no way of knowing which markers were still accurate. All those in Rocky Pass, a route less used than many others, were simply removed. Some things are worth paying taxes for. I’d trade the cost of a few missiles for Coast Guard buoys and markers, the Youth Conservation Corps, a better Tongass National Forest policy, and the Forest Service cabins.

Just ahead was where the tides meet. These places in the middle of a long channel are like a continental divide, where the water flows away to the ocean on each side. Beacon Island had a light that a boat crew could see when coming up from the south or in from the west and know it was the turning point. My chart tersely described the dredged channel there: “5 ft for width of 150 ft April 1966—Conclusion Island, Feb 1977.”

I veered off the usual boat route, heading east of Horseshoe Island. Crab pot floats were bright spots in the bay, and pairs of loons came close, but the camera was out of film and impossible to load in the steady rain. One of the most common animals of the whole trip was here, too, one I was unlikely to communicate with: the huge, two-foot-wide orange jellyfish Cyanea, which came pulsing by every mile or so. Their tentacles are toxic, and I gave them plenty of room, so as not to accidentally scoop one up with the paddle.

A long tidal flat lay ahead. It was only half an hour to high tide, and I could run out of paddling depth before reaching the Big John Bay cabin. One brief experience in the mud was enough, but there was deeper water off McNaughton Point. Around a spit to the north I looked for likely spots for a cabin, then saw the roof in a clump of trees to the right. Back around and up the slough, marked accurately on the topo map, almost to the doorstep.

On the open slope below the cabin was a field of fireweed, brilliant fuchsia against the lime green tidal grasses and the darker green of the hemlock and spruce. I stood there with a sudden grin, savoring the moment of awareness and color, then hauled up gear and was ecstatic to be there, out of the rain, despite an oil stove with only one cup of oil. This stove worked, and there were 10 gallons of fuel at Devils Elbow where it didn’t. Ah well, my clothes would keep me warm, and my own Optimus stove would cook my food.

The pile suit under the foul-weather jacket and pants had been warm enough during the day’s steady rain, despite a wet seat (seal that front-fly zipper), cuffs, ankles, socks, and head. I dried off and changed to dry clothes before dinner. After so many years in Hawai‘i it was a pleasure to wear a wool sweater. As a shift from dehydrated rations, I ate a can of pork and beans that someone had left here. More sugar than pork, said the label. Then I had a cheese fondue, and hot Jell-O for dessert. Between courses, I made up a glass of Tang with Lemon Hart 151-proof Demerara Rum. Umm! Everything is relative. Food I might scorn at home I purr over here.

A mousetrap was in the cupboard, and I set it before bedtime. About 2:00 am it snapped, and, half awake, I lurched over, found the mouse still scrabbling, dropped mouse and trap outside on the deck, and went back to the sleeping bag. In the morning I found the trap on the ground with the dead beastie, wee and thin and sodden from the rain. Once, long before, I had found a nest of mice in a cabin, carried them out to the river that flowed by the door, and tossed them in. One small mouse was still paddling valiantly in the chill water as she disappeared around the bend. Filled with self-loathing, I had gone back to the cabin. No mice scampered over my food and hair that night, but I kept asking, “Did you have a better right to the place than the longtime residents?” and “Mice have a place in the food chain. They eat seeds, convert plants to protein, and are food for the wolves and bears. Are you as useful?”

Now this second arrogant mistake. Communication with endearing creatures is supposed to be one of the themes of this journey. No more mouse murders. Just hang my food. I’ll put some cheese and oats outside for them from now on. Nice philosophy, Aud. When I tried it later, it took the mice out to the yard and lured a bear to the doorstep.

Journal, Day 42: Still raining. Fifty degrees now, and indoors without wind it is warm enough. My long underwear pants are Australian wool. They work well, and the top half is ideal, an old cashmere sweater. The boat needs a wash, so I’ve set it out on the deck to let it partially fill from the rain-gutter spout. I swab it out with the washcloth, empty some water out, deflate it halfway, and swab out the seams. I need a washing machine and dryer or some sun or a stove with lots of heat. I have plenty of fresh saltwater. I could do some writing about this trip while waiting for the rain to stop. In Tahiti once, in a small café, the restroom toilet wasn’t working. “Ca ne marche pas” said the proprietor. Ever since, my daughter Noelle and I express doubt by asking, “Will it march?” Can the tender feeling for this country emerge from the physical inconvenience? Will it march?

I was now 20 miles from Kake and the next resupply, a long trip for one day. I had one big meal left, a Spanish paella that called for mussels. Where could I find them in this mud-flat country? At least there was a large cast-iron skillet hanging on the wall. My six-inch-square aluminum frying pan would never march.

I needed binoculars. Flocks of sparrow-size birds were feeding on the muddy shore, running fast, their white bellies showing when the flock wheeled in midair. At noon it was still raining. This was Kupreanof Island I was on. Oh. It didn’t make much difference where I was. The only reality was the distance I could see. In the afternoon, I walked south and found mussels for the paella. Tomorrow I’d really have a light load – for one day. The sun came out; it lasted 15 minutes.

I paddled out, looking for the Goldstein Trail, marked on the map – I wondered if hiking this trail would save miles of paddling. I saw a swath through the woods, but it was deep in grass, with logs down across it. Struggling half a mile of it with even one load and I’d be happy to paddle a full day around the other way. Both wolf and bear tracks were on the mud flats near the trailhead. I took photos, comparing the size of my boot print to the bear’s paws. Same length, 10 inches. I had a book of animal pawprints, showing the differences between those of grizzlies and black bears.

Back at the cabin I pulled out the recipe for paella by Moira Hodgson in the New York Times. It was a combination of chicken and seafood cooked with rice and saffron that I had often made at home. Translating the ingredients into dried or canned items to pack and mail ahead had not been difficult. So now I made up the chicken broth from bouillon powder, stirred in the chopped fresh onion from Point Baker, and added the saffron, those expensive dried wisps of the stigma of Crocus sativa that give the whole dish flavor and a yellow color. Someone once said you could get a similar color and flavor using dried marigold petals. I tried it. Ugh! The chicken was canned, and the shrimp, parsley, peas, and bay leaves were dried, but the garlic, lemon, wine, and mussels were all fresh and pungent. The final steaming skillet had juicy mussels in their shells up-ended in golden rice that was slightly crusted on the bottom. Fresh lemon wedges alternated with strips of Spanish pimento across the top. A foil flagon of Australian wine sat next to it, beach asparagus was the side dish, and dessert was apples and blueberries flambés.

I packed to leave in the morning.

Journal, Day 43: It was a much better day. Had I really considered scratching the whole trip and taking the ferry out of Kake? I had. When I was wet and cold and shivering, nothing mattered but getting warm and dry. When I achieved that, the expedition was possible. Warm and dry with sunshine, I would tackle anything.

I left at nine o’clock on an outgoing tide, paddling down past McNaughton Point, hugging the starboard shore. A steady rain lasted past Horseshoe Island, and then, as the big Keku Strait opened up to the west, the rain stopped. Twenty-five miles ahead, across Chatham Strait, were the snowy peaks of Baranof Island. There was no wind and the water was calm. A cabin marked on Entrance Island was gone. Up to Point Hamilton and over to Hamilton Island. No cabin, though one had been marked on the topo. The isthmus was too thick with alder jungle to think of portaging across, so I paddled down the length of the island.

Three teenagers in a skiff came by and told me of the facilities in Kake. Where were the post office, groceries, gasoline? By the end of Hamilton Island I’d made 18 miles. A room and a shower would have been wonderful, but I wasn’t up to three more miles and hauling all the gear through town from the dock in search of accommodations.

The campsite I found in a small bight was fine. I checked the high tide time and simply pitched the tent on a Salicornia meadow. High tide was within 20 feet, but that was as high as it would be for the next 12 hours. Finish off the paella and off to bed to write the journal.

Whenever I woke during the night it was from some dream of great drama, full of emotional conflict, anxiety, and indecision. Often that just meant I was too warm. No rain. The body woke at six o’clock, and I unzipped the tent and stood up in the opening. The high glaciers over on Baranof were framed between the tips of islands. Off to the right was Grave Island, an ancient burial ground. I could hear the hum of the generators of Kake. I breakfasted, packed, and paddled toward Kake, aiming for the pier of fishing boats.

“Where can I do laundry?” I asked a fisherman.

“Right up there at the cold storage.”

Up at the plant I asked again.

“It’s for all fishing boat crews.”

OK, so I’m a fishing boat, in a small way. I walked in with a high school girl who worked there during the summers. Six dollars an hour to gut, clean, freeze, glaze in ice, and ship the fish. Next year the plant would have its own plane and would be able to fly fish out fresh, get them all the way to Chicago within 24 hours of the time they’d been pulled from the sea. I did a laundry load and took a shower in the women’s dressing room, repacked the boat down on the rocks, and paddled on to the main part of town.

Heading in to a small floating dock, I looked for the float where skiffs tie up, as they are the lowest docks to reach up to with my arms and lift myself out of the boat. Shores were easier places to debark, but on floating docks I didn’t have the problem of tides leaving the boat stranded or out of reach in deep water. Up at the head of the long pier and a road, I could see a U.S. flag and the green portable building that meant post office.

I tied the boat bow and stern with bowline knots and walked up the ramp. Half of its width was cleated with inch-high wooden strips; the other half was covered with rough sandy decking material for traction. High tide meant an easy slope, but now at low tide the ramp was steeply angled up from its rollers on the floating dock. Coming from Hawai‘i with its maximum two-foot tides, this was all a new system. Ingenious.

Striding along the dusty gravel road, I enjoyed walking on level land for the first time since Craig.

“I’d like some General Delivery mail, please. For Sutherland.”

“Oh, you’re Sutherland!”

The postmaster was happy to get rid of the pile: six packages and 10 letters. I bought supplies and wandered around happily, feeling at ease in this place. As at home in Hale‘iwa, I was one of a Caucasian minority. Kake is a native village where the population of about 700 is organized in an effort to provide jobs and good living conditions for all of the residents. I lugged everything down to the dock, where I sorted and stuffed and packed a box to mail home of gear, maps, and charts I no longer needed. Ahead were three weeks and 200 miles of no cabins, no towns, a portage, and the infamous Sergius Narrows.

A fishing boat, the 60-foot Sea Bound, slid in along the dock, tied up, and began unloading. The big Tlingit skipper walked over. By now I could predict the conversation.

“Where’d you come from?”

“Ketchikan.”

“In that?”

“Yes” with a wry smile.

He looked around for the rest of the expedition, then said, incredulous, “Alone?”

Sometimes the next comments were about insanity, but Sam Jackson knew the sea and small boats, and knew it could be done. He took me aboard, introduced his crew, and gave me instructions for reaching Gut Bay.

“Aim for Mt. Ada. The entrance to the bay is narrow, but if you cross Chatham Strait using the mountain as a landmark, you’ll come right into the mouth of the bay.” “Thanks, Sam. You know, you look to me just like the Hawaiians at home.”

Sam looked thoughtful. “Maybe I am part Hawaiian. My family is half Haida, half Tlingit, and we have a tradition that some of our ancestors paddled to Hawai‘i and returned here centuries ago.”

I thought of the 2,000-mile double-canoe voyages between Hawai‘i and the Society or Marquesas Islands to the south, dating from the fifth century or earlier, and how even the earliest Hawaiians had legends about a people who had preceded them, a smaller race who built stone walls and fishponds with miraculous speed. There had been a single tantalizing find of skeletal remains on the island of Kaua‘i that some scientists had thought showed Asian characteristics. Certainly it was possible. Although I had not heard before of Tlingit or Haida voyages in Hawai‘i, I was to hear many more times, here in Alaska and later in British Columbia, of the tradition of a Hawaiian connection. One Tlingit woman said of the voyagers, “Oh, yes. They brought back bamboo.”

Eager to be off while the seas held calm, I packed all the gear without really organizing it and shoved off into the placid water, heading for the Keku Islands. Now and then I stopped, let the boat slowly turn, and with a smile inhaled the whole circle of space and magnificence. In a mass of kelp I found a floating Japanese glass ball and took it aboard. I really had no space for souvenirs, but it is impossible to leave a glass ball.

I heard a whale breathe. She surfaced and went down 100 feet to my right. I stopped paddling and waited. Again she came up and blew, about 70 feet behind the boat, then again to my left, about 50 feet away. No flukes were showing as she dove. The last time, I took a photo as her back surfaced, and another as the dorsal fin came up. She was so long that there was time to advance the film between shots. White hide was visible under the mouth. Later I studied the photos and identified her as a fin whale; they grow to a length of 70 feet. She was definitely circling me, and I wondered if it was the yellow color of the boat or the rhythm of the paddle strokes that had attracted all the whales so far.

Rhythms are basic, from the time of the first heartbeat felt within the womb. Footsteps, bass viols, poi pounders, drums, the beat of a bird’s wings, the cadence of a crawl stroke – so many rhythms are part of our lives. Was it the paddle pulse or the possibility of a small yellow whale on the surface that had brought this fin whale to meet me? I knew only that I wanted to be swimming in the water with one someday. Roger Payne, in his book Among Whales, says that people spook out when they’re 10 feet from a whale in the water, and cannot force themselves closer.

I went on with a high sense of well-being, as if I were paddling 10 feet above the water. Small islands were ahead. I passed one with dazzling white beaches, like a South Pacific atoll, then the next one spun me toward it as if magnetized.

These were narrow limestone islands, and I had heard of quarries here. A physical oceanographer could look at my chart, #17368, and make some hypotheses about glaciers, and about sea floor tectonic plate movement, from the elongated northwestsoutheast island ridges and the ocean depths. There was so much to learn that I wasn’t learning in this steady push for distance, and with only my own data bank for reference.

I paddled in to barely floating depth, braked with the right blade to swing the boat parallel to shore, and swung out a booted leg. I stood up in the shallows and looked around. It felt right. I took the lifeline off my shoulder, lifted the bow of the boat onto the coarse sand, and carried a large rock close enough to loop the line over for a temporary mooring. I walked up to the forest edge, through the tall cow parsnips and ferns, and found a small clearing on the point of the island. It was invisible from shore, but something had said it was there. I went back and carried up the three loads of gear, then the boat.

From the new bottle of wine, which had been wedged in the bow, chilling as I paddled, I poured a plastic glassful, took it and the bottle down to the point, and nestled them in the rocks. The two liquids caught the slanting sun rays, refracting prismatic lights onto the wet pebbles. I went back and set up the tent, returned to the wine, walked back and sorted food, came back to the sea and sat there, sipping wine, eating Camembert and crackers and swiveling to watch the whole scene.

To the east the land was darkening. Night does not fall. It rises from the earth as the sun sinks low, sets, and embraces the land with its shadow. How could I describe this place? Words could only be read and the scene imagined. Even a photo could only be seen. It would not include the sound of the water on the stones, the scent of the spruce trees, the coolness of sea wrack under my hand, or the weary satisfaction of just sitting there after paddling six hours that day, and six weeks before that. The size of these islets and their details of sand, shell and rock beach, grass, driftwood, and flowers, the small woods back of the shore – these are proportioned to kayaks and close-ups, not big cruise ships or ferries. Those get a far outline of the shore, but their only close-ups are of the docks and the towns. This country is made for the pace of a kayak.

Up in the morning to leisurely packing, and to a fresh-food breakfast. I reread all yesterday’s mail. The schedule said Kingsmill Point that night and crossing Chatham Strait the next day. The weather might say something different.

People have asked, “What was it like, those long hours of paddling alone?” Each day the first half hour in the boat was full of protest, a feeling of awkward stiffness, and a certainty that I just wouldn’t be able to paddle far that day. Slowly the muscles warmed up, the brain became less aware of the body, and the automatic pilot took over, so that the steady rhythmic stroke went on and on like breathing, with no conscious direction or effort. After eight hours, the beat would still be steady and strong. It was stamina, not muscular strength, that kept the expedition moving.

Ahead there was always a goal. It might be a cove on a far island that I could see only on the chart, one I’d planned to reach when checking the map and chart the previous night. Before I’d be able to find the island, there would first be that far, pale blue point to pass. A darker ridge in front if it was about eight miles away, and before that, there might be the deeper blue-green outline of an islet only four miles away. At two miles I could discern an individual tree; at a mile I could see branches. Fifty yards in front of the boat, a gust of wind would hit the water, riffling it into a crumpled blue tissue, and I’d dig in with the paddle, anticipating the force of the wind. Always I was watching for a swirl of white water or an eddy indicating a rock just below the surface, and all the while my conscious mind was planning the building of a shanty in some hidden cove. Let’s see, eight by eight, a shed roof…

The wind stayed low and the paddling was easy, threading through the Keku Islands and crossing Saginaw Bay. En route was the second bear sighting: a black bear, hard to photograph against the dark rocks. A mile later, two humpback whales were leaping and twisting. They mate in the winter in Hawai‘i, but this looked like courtship behavior. They separated, and one came toward me, slapping her flukes. I was leery of a bedazzled whale who came straight toward me without circling, and I backed off into a kelp patch until she left.

At dusk I turned into Security Bay and found a spot on Round Islet. There was an 8.5-foot tide when I camped, and it wouldn’t be that high again until after nine the next morning, when I would be long gone. I slept warm and dry, and with a small islet’s assurance that bears were less likely to be wandering through.

At 5:00 am my internal clock said, “It’s time.” Cool daylight and a breakfast of oatmeal, but no fluids before the long crossing ahead. I loaded and pushed off. Chatham Strait was quiet, and the spire of Mt. Ada was clear. I pulled out a sheet of lined yellow paper, a letter from Hawai‘i I’d received in Kake.

“E ka moana nui, kai hohonu.

E lana malie kou mau ‘ale

E ka makani nui, ikaika

I pa aheahe malie ‘oe.

O great sea, deep ocean,

Let your waves float quietly.

O great strong wind,

Blow softly and quietly.”

I slid the paper into the clear plastic bag. On one side the folded chart showed an inset of the morning’s route. By flipping the bag over I could see the topo maps of Kingsmill Point and the edge of Baranof Island – and this incantation. I needed all the mystical power I could touch for the crossing ahead. With such a gentle sea, the 12 miles should have been a four-hour crossing, but my right arm was painful, and six hours was not enough sleep. I sang and stroked, chanted and dozed until the narrow mouth of Gut Bay opened ahead. Once inside, I laid the paddle across the boat and said a soft “Mahalo,” thanks. I paddled in, marveling at the sheer 1,000-foot granite walls, and at the starfish, each hanging limp by one arm just above the low tide mark. A lopsided smile. They looked the way I felt.

The fifth hot spring of the quest was supposed to be in Gut Bay. “First stream on the north side,” said the NOAA and USGS manuals. First from the mouth of the bay or from the head? I wondered, but turned toward the first one in. It was a big alpine creek, splashing down clear and cold through fallen trees and tumbled rocks. I landed and searched. Very cold. I went up a hundred yards and found an eight-foot-deep pool at the base of the long slide of a waterfall. Did it look a bit cloudy in the middle? The scientific way to test it would be with water samples, thermometers, and chemical analysis. Unscientific was to peel off and dive in. It was not hot. I shivered back into my clothes, launched, and paddled south to an island shown on the topo. No landing was possible on the sheer rock sides, but there was a small bay beyond. A stream bounced white riffles into the sea; lupine and high grassy areas indicated a clearing. I checked first for the seaweed and driftwood marking the high tide line, and then to be sure that there were no bear signs, and set up my home.

I was now on the topo map I had been astonished by months before. Of all my maps, this one showed the most contrasts and features, but the reality far surpassed the map. Across the bay the wooded ridges rose to 2,500 feet, but behind me, the gray Matterhorn shape of Mt. Ada was nearly twice that. An icefield came almost down to camp. I could have walked up and chunked ice into my wine glass, but the 38-degree stream was cold enough. I used the awl of my Swiss Army knife to skewer marinated artichoke hearts from their jar.

A powerboat was coming, a sportfishing type, but it went on up the bay, not noticing my camp. If I wanted privacy, maybe I should have hidden the boat, but I usually left it conspicuous, in case I was eaten by a bear and friends had to search for a missing paddler. At 8:30 pm there was another boat, a small sloop under mainsail and outboard, which seemed to be a single-hander, but it, too, went on up the bay.

Gut Bay. By now I realized that gut had several meanings, one of which was “a narrow passage or gully as of a stream or bay.” Was that where gutter came from? I went off to bed to small stream sounds, gurgle, giggle, plink, and a throaty chuckle. I went to sleep laughing. No pressure tomorrow.

During the night I looked out to check the sounds. This was Baranof Island – Russian history, alpine scenery, hot springs – and, along with Admiralty and Chichagof, the other ABC islands, it was also known for grizzly bears.

It lightened into a misty morning, but by ten o’clock the sun was above the shoulder of Mt. Ada, shining bright on the shore across the bay and filtering through the hemlocks and blueberries here. I gave the arm some hot-water-bottle-in-the-sleeve therapy, as I couldn’t close my hand when I awoke. Slowly it became more flexible, though still numb. Maybe it needed soaking in the Baranof Warm Springs. I hoped their tubs were deep ones, not U.S. standard, but they were still 30 miles away.

The single-hander sloop came by again. I yelled and he came in close, so I paddled out, and we exchanged stories. Glen Crum had taught himself to sail on a Montana lake, then put the boat on a trailer to the coast and started a voyage north from Vancouver. We took my canoe aboard and sailed three miles up to the head of the bay. Glen hiked upstream while I caught my first fish of the trip, a three-pounder. It was not until weeks later that I could identify it as a Dolly Varden. Glen came back, admired the catch, and offered to bring a chilled wine to a fish dinner. Yes! Fillets poached in butter, Lyonnaise potatoes, steamed plantain from the shore, mussels in marinade, wine, Hawaiian coconut-haupia pudding with blueberries, and then brandy to toast the place, the sea, the day, and the solo travelers. After dinner I took Glen to his boat, and gave him the glass ball I’d found near Kake.

As darkness rose to meet the coral clouds, I paddled on through a narrow slot just west of my camp, into an inner harbor, a cathedral place in which to talk to the ancient Tlingit gods. Slowly, soundlessly, I moved back to camp, carried up the boat, heated some milk, and sat sipping it, postponing sleep, not wanting this day of sun and glory to end. I came to Gut Bay not knowing what it would be, not knowing it would surpass the map.

2 ½ cups water

3 packets chicken bouillon

2 teaspoons saffron

1 chopped onion

¼ cup olive oil

1 12-oz. hot Portuguese sausage or 5-oz. can ham or both

4 cloves garlic, minced

1 can Spanish pimento, diced

1 ½ cups short-grain rice

3 teaspoons chopped parsley

1 bay leaf

1 cup dry white wine

2 teaspoons lemon juice

1 cup freeze-dried peas

2 dozen fresh mussels

1 5-oz. can of chicken, shrimp, or clams

Heat water; add bouillon, saffron, and onion. Simmer 15 minutes. In a big skillet, heat oil, add sausage, ham, garlic, pimento. Stir in rice. Add broth, parsley, bay leaf, wine, lemon juice and cook 10 minutes. Salt to taste. Bury in rice a canful of chicken or shrimp or clams or all three. Add mussels so that thier edges will openfacing up. Cover with foil and bake at 325°, or cover and cook on the stove over low heat, until liquid is absorbed and mussels open. Remove foil, decorate with lemon wedges and parsley or fresh wild herbs or Salicornia.