9

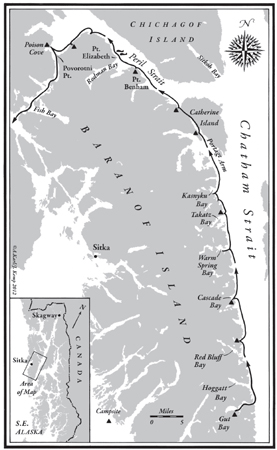

The next day I paddled out of the enclosed alpine peace of Gut Bay and into a headwind. Cove by cove I fought my way north, paused, and fought again. Two miles past the headland of Red Bluff Bay, I pulled out of the wind and into a quiet cove. In the rare sun, a stream ran shallow over flat granite. Yellow marigolds blinked in the grass.

I put the last of the wine to chill in a shaded pool, stripped naked, washed hair, body, and long underwear, and put us all to dry on the warm rocks. Blissfully I sat there and finished a Sunday crossword puzzle, carefully hoarded for a proper moment. I kept watching the whitecapped seas out beyond the cove while my mind played leapfrog.

Up among the trees was a small hollow, like a nest, a place to pitch the tent and curl up for the night, but I felt I ought to push on while the wind was down. Next time you do this, Aud, allow time to stay in good places. Next time! No, I think not. There must be better ways to see this country than 20 percent good stuff and 80 percent bloody hard work and careful survival. A better boat? I didn’t know that this wild country would become a passion, that I would come every summer for the next 20 years, in eight different boats, most of them an improvement over the previous model.

By 11:00 pm the sun had set. I had made a few more miles, but the seas and wind were up again. A small cove showed on the topo before Nelson Bay, but an ebbing tide had barred the entrance, so I came ashore on a gravel spit, set up the tent and sleeping bag, left everything packed, and slept. It was possible to do this only when a careful look at the tide table showed that the tide was going out and would not be up to the level of the boat again until I was awake and ready to launch. Even so, I tied the boat on a long line to a rocky crag. Barring tsunamis and bears, I could sleep uninterrupted.

Up at five next morning, and away at six. By seven, the headwind had risen to 20 knots. I toughed it out until 11 am, then came ashore for lunch. A seal kept popping up close to shore and twitching his whiskers. “What is that I smell? Can it be? It is, it is! It’s Szechuan eggplant!” I giggled, and he vanished.

Three more hours against the wind and I’d covered the mile into Cascade Bay. A massive cataract of white water drained the high lake system and pounded into the sea, pushing an aerated mass out to form a clear line between the green lake water and the blue salt sea. In the bay to my left was a bit of flat land. I maneuvered in to a narrow shore where there were the fewest barnacles. The tide was outgoing, so I had 20 minutes to check for campsites before the boat would be hard aground. Between two big spruce trees I found an open grassy flat, but was there freshwater? My supply was down to a quart, and it would be impossible to paddle close enough to that huge waterfall. Ah, a trickle of a stream close by. As I came back to paddle the boat around, a river otter slid into the water. Not a sea otter, this was a close relative of Gavin Maxwell’s otters in Ring of Bright Water in Scotland. The family includes skunk, mink, marten, weasel, and badger. Ten years later, I would paddle in Scotland and walk down to Camusfearna, the poignant site where Maxwell’s house had burned, killing Edal, his second otter.

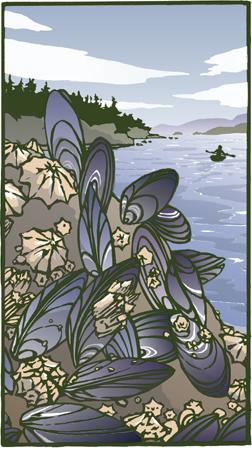

Here in Cascade Bay I built my home: a drift-plank desk propped on two roots of spruce, another drift plank for a kitchen counter, with the bedroom tent beyond them. I sorted through the food sack and decided on a housewarming dinner of cioppino, using fresh mussels from the rocks here. I was hungry enough to want to eat them fast, without shucking each one out of its shell as I ate, so I steamed and shelled them first, using the broth to reconstitute the tomato, wine, and herb sauce that I’d oven dried at home into a leathery slab.

I stayed alert for PSP symptoms, but none appeared, and it was weariness, not poisoning, that staggered the body off to bed for 10 hours of deep sleep.

The north wind on Chatham Strait is up to 20 knots when I wake in the morning. I wait it out: sit and observe cloud patterns, tree forms, grass blades; paddle out into the bay without a load and look up at the high blue glaciers clinging to the spine of Baranof Island; listen to the quiet sounds of this world.

I should travel every other day. Derigging the tent and tarp, packing up the kitchen, carrying gear down to the shore, and packing the boat all takes two hours. Then in the evening two more hours to carry gear, set up camp, fix dinner, and get to bed. It would be better to paddle a long day, come in late, set up just tarp and tent, have just soup, and get to bed. Sleep late in the morning. Have a leisurely day of writing the journal, exploring the woods on shore, studying the chart of the next day’s route, resupplying the water, fixing a fine dinner, doing half the repacking, and then early to bed and an early start in the morning.

At noon, a humpback whale was blowing and moving south out in the strait. At two I began packing and at four shoved off, determined to make Baranof’s Warm Spring Bay that evening. With the wind down to 10 knots, the six miles took three hours. Five yachts and a big seiner, the Sea Comber from Anacortes, in Washington, were there at the small dock.

Warm Spring Bay was just “the way it s’pozed to be.” The photo I’d seen in Stephen Hilson’s book was true, perfectly proportioned and not distorted by a telephoto lens, which foreshortens the distance. The waterfall was huge and thundering. A former resident had moved away, maddened by the constant roar. Eight hot springs oozed out of the slope; three had been tapped for use, to warm the few houses with steam heat, to make hydroelectric power with a Pelton wheel, and, best of all, to fill hot tubs in a funky old bathhouse.

I inquired at the small general store on a high pier above the floating docks. Two dollars for the use of the bath, two fifty with soap, towel, washcloth, and mat. I had earned the deluxe version and had my choice of a plywood or galvanized tub. The metal one was reminiscent of the childhood round washtub, which I could no longer sit cross-legged in. This was different. Searching for replacements for the old plywood tubs, the owner, Wally Sonnenberg, had come across these in a farm catalog: galvanized horse troughs. Long enough to lie full length, shoulder deep when filled with water, nonmolding, and nearly indestructible: These were ideal. You mustn’t turn off the hot water, a sign warned, because compression steam would burst the pipes. The drain was a two-foot-high hollow plastic pipe. When the water was more than two feet deep, it simply overflowed down the inside of the pipe.

I soaked and steamed for an hour, then, clean and limp and blissful, walked the trail up to the lake and back. At dinner aboard one of the yachts, the crew gave me doomsday predictions of the impossibility of this voyage on which I’d already paddled 400 miles. Yachtsmen seldom really comprehended boats this small, with neither sail or motor. Not until the following year did I stay long enough to better know and appreciate Wally and to meet Ben Rowely, the gentle 80-year-old carpenter who lived on his boat and did jobs throughout southeast Alaska. Then, too, I met Curtis Rindlaub from Connecticut, who was paddling south from Glacier Bay. We exchanged campsite information, north for south.

It was getting late. At 10:00 pm I said good-bye and paddled down the bay. In the first cove, a house occupied the only flat ground. In the second, a crunched cabin took up the space. I went on, no campsites, so just kept paddling out of the bay into the night. There were oily swells, but no wind. By flashlight I checked the topo map and chart and plotted a compass course. No offshore rocks or reefs. Keep paddling. By midnight it was too dark to see the water, but I could make out the outlines of the 2,000-foot-high mountains to my left. A wave lifted the boat. OK, so there’s a bit of a swell. It’s not breaking at the top or I’d see the phosphorescence and the white water and feel the wind. Keep paddling. Something bumped the boat hard. It’s just a log; you’ve hit them before. There’s nothing out here you don’t already know. A big splash? Just a seal. I was eating from a bag of chewy candy from the little store and thinking,

“Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

for black licorice.”

Finally, by 4:30 am, I could read the map and chart, and figured by the mountain contours and the coves that I was past Takatz Bay. To my left was a landing beach. Ready for sleep, I pulled in, carried up the gear and then the boat, and set up the tent as a refuge from bugs.

Across a stream, a dark animal, bigger than an otter, with a thick, furry, blond-striped coat, looked at me and unhurriedly, disdainfully, walked into the forest. A red squirrel chattered and ran toward me. Was I a refuge, a better choice than the other animal?

When I awoke three hours later, ready to paddle again, there were parallel scratches on the side of the boat where I had laid a smelly bait herring two weeks before. Later I checked photographs in Alaska Geographic’s book of mammals, and found that my bushy animal was a wolverine, who has a reputation, shared with the tiny shrew, as the most ferocious animal, pound for pound, in the world. A wolverine’s fur is valued for its durability, not for its mythical quality of being frost-repellent.

The tide would be high in another hour, and Portage Arm, where I needed the high tide to cut down the carrying distance across the isthmus, was still nine miles away. At least I had the high to launch with now. Around a curve I passed Waterfall Cove, hearing its roar back in the cleft. Just past Ell Cove was a pearly sand beach that swung me hard left to a tiny shore, 30 feet wide and U-shaped. The rocks on its sides were quiet sphinx paws, furry with black moss, and the head and body of the rock beast wore a matted coat of flattened crowberry – so like our Hawaiian mountain plant that I laughed, “Hello, pukiawe. Nice to see your relatives here.”

Trudging on the fine sand was like walking on sugar: the only place in Alaska I’ve ever seen such a beach. Across eight miles of the pale blue Chatham Strait was the darker blue of Admiralty Island, with everlasting snow on the ridges. Admiralty has one grizzly bear per square mile. I paddled on into Kasnyku Bay to check out the “abandoned lighthouse” marked on the chart. It was outhouse-size, not big enough to use as a shelter cabin.

A skiff came powering up to check me out. Back in a corner of the bay was the modern Hidden Falls salmon hatchery, which the staff proudly escorted me through. I felt grubby and out of place in this world of chrome, plastic, steel, motors, and flush toilets. I took the crew’s recommendations for campsites and paddled on.

That evening I found a good spot. At sunset I gathered mussels, the giant Mytilis californianus, tearing them loose from the byssuses, the threads that held them to the rocks. They were rare this far north. Had we really called them horse mussels years ago in Southern California and only used them for bait? The middle-sized ones were more tender than the seven-inch-long monsters. I made a fire on the beach of driftwood and dead alder sticks, let it burn down to coals, then covered it with a thick layer of fucus. I scooped a nest for the mussels and covered them with more of the seaweed. While waiting, I unpacked the sleeping bag and fluffed it, inflated the air mattress, and laid them inside the tent.

I minced garlic into the smallest pot, put in a chunk of butter, and laid the pot on top of the steaming seaweed. I brought the chilled bottle of wine from the stream, undid the seaweed nest, lifted out each opened mussel and dipped it into the garlic butter. Ah! The smoked, steamed flavor, the taste, smell, and texture of the mussels, the sounds of the sea, and the deep colors of the sky – all five senses were melded in a rich evening harmony.

A day later, just before high tide, I paddled to the east end of Portage Arm. Both chart and topo map indicated a water route through the isthmus, but it did not exist. Not even the highest tide would connect a waterway through the bogs and logs. When the weight of the glaciers over all this land for centuries was gone, the land began rising. Isostatic rebound, the geologists call it.

I tied up the boat and walked to higher ground, scanning ahead for the best route. A neatly trampled path led through the grass. How nice! Oops. I bent a knuckle into the pile of bear crap. Cold. At least she hadn’t been here within the last hour or two, but from the turd size it was probably not she, but a large he. Sing loudly, Aud, as you portage. How about that old French song that sounds like a crew of voyageurs? Lustily, now:

“Chevaliers de la table ronde,

Goutons voir si le vin est bon…”

I picked up the boat and carried it on my head, with a loaded pack frame on my back. The trail disappeared to the right into the woods, so I bushwhacked over logs, through shoulder-high fireweed and cow parsnip, singing loudly, to a point by a spruce tree where I could see water ahead. Two more trips took me through all the verses of “Chevaliers,” all the parts of plucky “Alouette,” and several repetitions of the mournful end of the jolly swagman in “Waltzing Matilda.” Any bear would have fled by now at full gallop.

By the time all of the gear was down to the water again, the tide was in full retreat, too. I would carry a load to a point, and by the time the other bags had been brought there, the water had receded. Leapfrogging loads, I finally caught up, piled the bags in, and then, in water too shallow to float the boat with me aboard, hooked the lifeline to the bow and started towing, wading through the shallows. I was glad that I hadn’t deflated the boat. In the five minutes it would take to pump it up again I would have lost the tide.

At 10:00 pm I came out of the inlet and went along the south shore to get water from a creek, then over to Dead Tree Island. Three cabins were on the topo map, but as usual, none remained. It was windy and cold. I paddled on to Eva Bay for the night.

In the morning’s first sleepy reconnaissance I could see the two-mile-wide entrance from the north-south Chatham Strait into the east-west Peril Strait. It separated Chichagof Island to the north from Baranof Island behind me. I had bypassed the usual ferry and small cruise ship route by angling through Portage Arm.

A skiff was drawn up on shore a half mile away, with only one slim person walking about. Curious, I came across, and we compared notes as soloists. Ted was 18, and he was celebrating his first summer out of school by seeing as much as he could of Alaska in a month. He used a 14-foot skiff with a small motor and tied the heavy boat on shore at high tide each night, then set up his tent. Hmmmmm. A lot could be said for motors, especially against headwinds. He couldn’t portage the isthmus, so would be heading east around Catherine Island. We exchanged campsite information, and I paddled on west into a 15-knot headwind. I made one mile in an hour and a half.

Just ahead, a stream was on the chart. I came ashore saying, “Well, I may be here for a while. May as well find a good campsite.” Though the wind made travel nearly impossible out on Peril Strait, the day was pure sunshine, the fourth whole day of it so far in the 85-day trip.

Tucked back in the trees was a clearing. By 11:00 am I had built a kitchen counter at stand-up height by placing a drift plank across the limbs of two small spruce trees. Drift plywood made a table for dining and library. The tarp made a windbreak wall, the tent was set up for the bedroom, and the wine from the Warm Spring’s store, the juice, and the cheese were chilling in the stream. The laundry was hung to dry, and a piece of seiner netting from the beach provided a hammock, as I’d sent my small one home.

I lay bare in the sun, listening, dreaming, melting like a lighted candle into the earth. It was strange to see my bare feet again. They usually went from boot to bed to boot again, without taking off the socks. They looked quite fragile. My hands, however, are tools – pliers, carabiners, vise grips, antennae, turnbuckles. I should spray them with Rustoleum. No sense trying to grow long nails or putting on polish. Only my toenails are painted pink.

Every hour I’d walk out and look northwest. I could see eight miles – of whitecaps. This was Peril Strait at its loveliest for a sailor in a sloop or ketch going east, but not for me, a paddler with an inflatable canoe going west. The wind continued at a steady 15 to 20 knots.

I was musing about the use of the words canoe and kayak. In Hawai‘i I had always called my boats canoes. Wa‘a is the Hawaiian word for canoe, and it is the indigenous craft, adze-carved from a log and balanced by an outrigger or another hull. In northern Alaska and Greenland, the kayak had evolved – a narrow, fully decked hunting weapon to carry the hunter and his spear within range of a seal or walrus. Now I was in Alaska, but not in kayak country. This was the southeast, where Tlingit and Haida had paddled single-hulled, undecked, adzed boats. My plastic inflatable needed a new word. Until it was coined, I’d continue with both canoe and kayak.

Dinner was a tuna-rice casserole, chablis, and a salad of beach asparagus and goose tongue from the gravelly point beyond camp. Dessert was apple Betty made from stewed dried apples with a granola bar crumbled on top. After dinner I had tea with rum: an affinity there. I might be holed up here for three nights, as on Strait Island, but now I had a stream and at least one day of sunshine.

There is a rhythm to this country: hard paddling and rest, rain and sun, wind and calm, high tide and low tide. A sense of space and the far-off throb of a diesel tugboat. A forest enclosure and the chirp of a tiny brown bird. People and a sense of being human, then a week of being a solo animal in an animal world. A dozen dragonflies hovering, then soaring out of sight. The mite of a red spider crawling over my toe. Strange that I kill mice and carefully move spiders.

At 8:00 pm the temperature was a pleasant 53 degrees in the shade. If I’d had any thought of night paddling, I dropped it. The seas were still whipping by at 20 knots. Under my elbow as I wrote, the space was filled five inches deep with pieces of spruce cones that a squirrel had carefully shredded. Pine nuts from piñon trees I knew, but spruce nuts? The mind was reluctant to let go of the day, but the body said it was time to sleep.

I woke at four o’clock and from the tent door saw the trees bending in the wind. At six I went stomping out to the shore in boots, jacket, and long underwear. Wind. OK, back to bed and slept until eight, then up to a cloudy sky. A ferry came up the strait from the northeast, timing the tide to get the noon slack at Sergius Narrows. Coffee to warm my hands. How different the mood when there is no sun. It’s about 24 miles to Poison Cove, my next goal. One day of tailwinds, two normal days, and who knows how many of this kind.

A leisurely breakfast of an omelet with a topping of crumbled bacon, smoked salmon, and onions. By 10:30 am the sun was out briefly, and my morale was back in high gear. Even against the wind I should be able to make the seven miles to Rodman Bay.

Getting into the boat for takeoff was always a precise maneuver. After everything was stowed and the boat afloat, I’d take the end of the lifeline off the anchor rock and loop it over my shoulder. From the left side always, like getting on a horse, I’d swing up my booted right foot, shake off the water, put it across, sit carefully in, then swing up my other foot, let it drip, and place it on the gunwale. Only in Alaska, where there was such quiet water on the shore, could I do such a neat takeoff. In Hawai‘i, where the surf was usually breaking, it was always a system of timing the wave sets for a lull, throwing the body into the boat, and paddling madly before the next wave crashed. No precision, just get the hell offshore.

An incoming tide, an outgoing wind, and five hours of paddling got me to the edge of four-mile-deep Rodman Bay on the south side of Peril Strait. There was a small beach and a clearing, with the sun coming through an old partially logged area to the south. There was no creek, but I had brought three quarts in the water bag, which still smelled faintly of the wine it used to hold. On shore was a bundle of 23 logs strapped together. In the parlance of logging, the specific name really is bundle, I found out later. Across the strait was a logging camp, and False Island, a Young Adult Conservation Corps camp. I sat on a rock at the edge of my clearing and looked out. A sailboat went by, main and jib raised, making good time. I wondered where they would anchor, or if they would sail all night.

I awoke at 5:00 am to solid fog with 50-foot visibility. I unfolded the chart and figured a compass course. Point Benham to Point Elizabeth, 280 degrees uncorrected, 252 degrees corrected, allowing for an easterly compass variation of 28 degrees. My course was often zigzag in this rudderless boat, but there was no wind. I was powering the stroke and figured two hours for the four miles. I overcorrected the course a bit so as to hit land and then turn right, rather than err to the right and keep going up the strait for miles in the fog.

In less than two hours trees appeared suddenly in the mist. As happy as a navigator seeing land ahead after crossing an ocean, I turned right and rounded Point Elizabeth while the sun burned through the fog, then clouded over again. Another two miles, and I saw a huge rusty winch on the shore. Was it from some shipwreck or from an old logging camp? I paddled toward shore to see it closer and to make a pit stop, but I was floating on something solid – fish.

I secured the boat, rigged the pole, and cast out. Ten casts brought me a five-pound humpy salmon. Five more casts brought an eight-pounder. By now I was wearing boots full of water from wading out deeper than my boot tops to unhook the lure from the kelp. Could I have gone ashore and peeled off the socks and trousers first? Of course, but one does not always act rationally when converted from gentle paddler into mighty predator. At least the $36 for the nonresident fishing license had paid off. Cleaning the fish, I found that both had eggs. Ah, caviar for the morning omelet.

En route again, I met and talked with a friendly couple aboard the Skookumchuck, a ketch from Seattle. I was so bedazzled I forgot to offer one of the fish. Around Nismeni Cove was a small stream, a good place to cook dinner. I filleted the smaller fish and had two big slabs of meat. The grill was scarcely large enough for this size of beast, but I cut chunks, swabbed them with butter and shoyu, and kept pushing alder coals under the grill. I dipped the red roe into boiling water for a few seconds, then scraped the eggs from the membrane, salted them lightly, and bagged them.

An hour later, full, I waddled back to the boat and paddled away from the kitchen site, wondering why waddled and paddled don’t rhyme. Thoughts of bears were always there. I should cook and eat at one place, sleep at another when I’m wafting odors of salmon.

Two big ferries have gone by today. I’m right on their route and their radar wouldn’t pick up this PVC plastic boat, but I’m safely hugging the shore and out of their way.

Just past Rocky Point I found a camp spot, drank hot milk with brandy, studied the topos and the charts, and recalled all the advice for Sergius Narrows, two days from now. Three miles ahead a ferry came out from behind Povorotni Island, indicating the route.

I put the second fish into a heavy double-folded plastic bag, then weighted it with rocks in a stream pool to refrigerate. Building a smoke oven to preserve it could be a full day’s project. I went off to bed in a dry tent – there’d been very little rain for two weeks.

Breakfast was salmon poached in butter and the caviar omelet. Plenty of protein. I felt like some Russian czarina, but they never got to Alaska. Are there salmon in Russia, or did Catherine the Great have only sturgeon-roe caviar? The Japanese now have red ikura on their sushi, imported from Seattle and Alaska. But Aleksandr Baranov – manager of the Russian-American company that established a fur trade based in Sitka, who built a “castle” on the most prominent waterfront hill and after years of hardship finally furnished it with luxuries from Europe and Asia – surely Baranov found that the little bubbles of salmon caviar burst in your mouth with intense flavor.

A big tug with a barge was heading toward Sitka. A 400-foot ferry would be difficult enough to get through the angled route of the narrows, but a barge on a tow line cuts corners like a trailer. Ah! The tug paused and shortened the towline, winching it in so that what was three tug lengths between them was now less than one. It disappeared around Povorotni Island as I packed and launched.

I angled over to Poison Cove to see if a cabin marked on the topo was still there. In 1799 a team of Baranov’s men, hunting for sea otter furs, camped in the cove – a colorful group of small agile Aleuts in their skin kayaks, fierce local Tlingits in cedar log canoes, and burly Russian overseers. They are said to have feasted on mussels, and over 100 men died from the effects of a “red tide.”

Now the cove was filled with floating logs, tightly corralled and waiting for a tug to haul them out. The cabin was there and occupied by Paul and Susan Hennon, who were doing research on the cedar trees. Throughout southeastern Alaska, cedars had been dying; in some forests, every bare tree was a dead cedar. The Hennons were investigating: checking aerial photos back to 1927, making microscopic examinations of live and dead tissues, collecting fungi, and doing root excavations of live, dying, and dead trees. They were especially trying to find if this was a problem caused by humans.

It was my first long conversation, except with myself, since Gut Bay. We talked with the ease of old friends about fungi and hot springs, botany and history, food and fishing. They had been at Poison Cove since June, and were coexisting with the brown bears that seemed to live across the cove. As I walked back along the shore to my campsite, I checked the sand carefully for pawprints. So far on the trip I had seen two black bears from afar, but it was the brown bear, the grizzly bear, who had the well-deserved reputation for an unpredictable temper; for attacking and chewing up people; in short, for most of the gruesome bear stories that are told everywhere in Alaska. Ursus arctos, formerly horribilis: a creature of nightmares that come true.

At six in the morning I sorted maps, packed, and carried gear to the boat. Neatly imprinted in the sand were bear tracks that had not been there the evening before. They led up to the edge of the forest, 30 feet from the tent, and then went back along the shore, past the cabin, toward the other side of the cove. It was reassuring to think of a bear on an evening stroll, simply coming to check out a new scent, and then returning on her usual route. Still, how far had she come padding into the forest on the soft duff where I could not see her tracks? Did she sniff at the tent screen, a foot from my head?

1 18-oz. jar chunky peanut butter

1½ cups honey

1½ cups or more powdered skim or whole milk (not instant)

Mix together into a stiff dough. Add nuts, raisins, or chopped dates if desired. Pat firmly into two nine-by-nine-inch pans. Cut into bars or squares. Wrap each piece in foil. Pack in ziplock bags. Make and wrap at home no more than two days before departure. Make them too far ahead and you’ll eat them all before you go.

Two of these every day for lunch, plus dried fruit, fruit rolls, nuts, gorp, granola bars, and juice or water will keep you paddling.