Finland is a land of lakes, forests, and open countryside. The Finns call their forests “green gold,” as they provide the raw material for the paper and cellulose industries, both of which are major sources of wealth for the economy. Finland also leads in the international field of forestry research and sustainable development.

Most of the country is topographically low, with the highest hills located in Lapland. Eastern and southeastern Finland are characterized by a large number of lakes, while the west coast is very flat and prone to flooding. A glacier molded the countryside during the last Ice Age; you can see the large granite boulders that were left behind after the glacier melted.

The total area of Finland is 130,500 square miles (338,000 sq. km). The distance from the southernmost town of Hanko to the northernmost village of Nuorgam is measured at 719 miles (1,157 km), while the furthest distance east to west is a much narrower 336 miles (542 km). Finland is situated in the north of Europe between latitudes 60° and 70° and between longitudes 20° and 32°. he Arctic Circle runs through northern Finland, just north of Rovaniemi, and most of Lapland lies above it.

Finland shares a 381-mile (614-km) land border with Sweden to the west, and a 457-mile (736-km) border with Norway to the north. The eastern border with Russia is the longest at 833 miles (1,340 km) and is patrolled by both Finnish and Russian border guards. This border marks the boundary of the European Union with the Russian Federal Republic and has been the backdrop for many spy novels set in the Cold War era. In the south, Finland borders on the Gulf of Finland and in the west the Gulf of Bothnia, both of which are part of the Baltic Sea. The length of the entire coastline is about 2,860 miles (4,600 km).

Water makes up around 10 percent of the total area of Finland. Forests, mainly pine and spruce, cover 68 percent, and 6 percent of the land is under cultivation, with barley and oats as the main crops. The remaining terrain includes a great deal of marshy land. There are 187,888 lakes in total, so the name “land of a thousand lakes” is no myth, but rather an incredible understatement. Finland’s 179,584 islands range from small skerries and outcrops to those with large inhabited towns. Nearly 100,000 of these islands are located in the lakes. Owning an island—or even several—is not unusual in Finland, and every Finn dreams of a house on a lake or by the sea.

Europe’s largest archipelago lies off the southwest coast of Finland, and includes the Åland islands (Ahvenanmaa in Finnish), which are an autonomous province of Finland situated between Finland and Sweden. Their status as a demilitarized zone was decreed by the League of Nations in the 1920s. More than 90 percent of the population speak Swedish as their mother tongue.

The largest lake, Saimaa, is situated in southeast Finland. The main Finnish lakes form five long, navigable networks—in fact it is difficult to determine where one lake stops and another starts. There are still some car ferries in the more remote parts of the lakes, but bridges have replaced them in more densely populated areas. It is worth remembering that roads have to go around the largest lakes, making journeys long.

The numerous rivers provide hydroelectric power for the country. Salmon gates have been built on the traditional salmon migratory rivers. There are 5,100 rapids in Finland, the largest being at Imatra on the Russian border. These are now harnessed, but are sometimes released on a Sunday for the pleasure of tourists, and are a magnificent sight. From nearby Lappeenranta you can travel along the Saimaa Canal to Vyborg. If you want to do this trip, check with the tour company about whether or not you need a visa. The canal is leased to Finland by Russia, and runs through Russian Karelia to the Gulf of Finland, providing access from inland lake harbors to the oceans of the world. The city of Viipuri, which was the second-largest city in Finland before the Second World War, was ceded to Russia after the war.

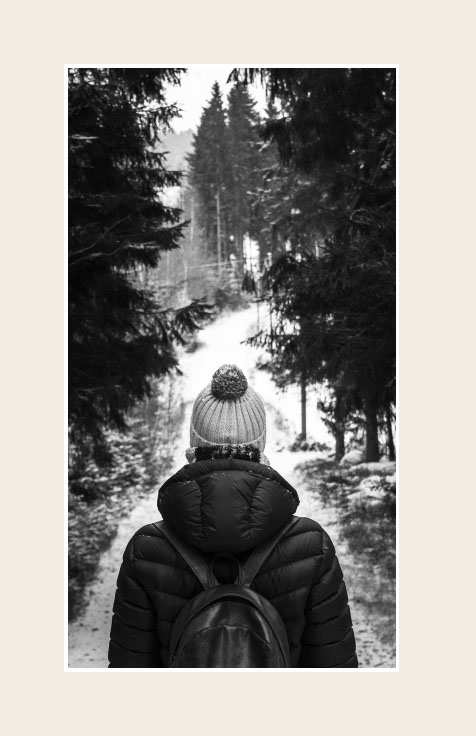

There are four distinct seasons in Finland, and they are startlingly different from one another. The longest season is winter, when frost and snow turn most of the countryside into a picture postcard. In Lapland the first snow can fall as early as September, and the winter does not come to an end until April or May. In the south the winter is much shorter and milder. Inland, the country is much colder and drier than the coastal areas. The temperatures in the north can fall as low as -40°F (-40°C). Lakes and coastal waters freeze in the winter, and the ice usually becomes thick enough to support traffic, which considerably shortens some journeys. The snow is at its thickest in March. Large quantities of snow are removed from the city centers to the outskirts for ski tracks and skating rinks. Icebreakers keep the main shipping routes open. The cost of the winter is huge to the Finnish economy.

Spring is dramatic, and can arrive suddenly, the ice on the lakes melting quickly. The summer can be very warm and dry, especially away from the coast, and daytime temperatures can rise to 86°F (30°C). Record temperatures are due to the continental weather coming in from the east. The west wind brings milder, wetter weather. Without the effect of the Gulf Stream, Finland would be a very cold and inhospitable country.

The Finns adore their short, precious summer, and enjoy every minute of it. Cafés spread out on to the streets, beer is consumed in large quantities on terraces, and sun worshipers fill the beaches. The gloriously colorful fall is a very popular time to go trekking in Lapland.

Because the lakes are shallow, the temperature of the water can be as warm as 68°F (20°C), making swimming in the summer a very pleasant experience. However, the Finns also swim in the lakes in winter—a hole is cut in the ice specially for them. This invigorating activity is said to cure many ills, and is certainly not for the faint-hearted! The annual world ice-swimming championships are held in Finland every winter.

The weather is very variable, and talking about the weather is something of a national pastime. Every household has an outdoor thermometer, because it is important to know how much or how little clothing you will need outside. Temperatures can change very quickly. Thunderstorms are common in the summer.

Days are short in the winter and long in the summer. In the north, the Polar night means that the sun doesn’t rise at all for several weeks. In summer there is continuous daylight in Lapland for about two months. Even in the south the sun only sets for a short while in midsummer. The magnificent light show of the aurora borealis, or the northern lights (the Finns call them “fox fire”), can be seen on clear, dark nights, on average three out of four nights. The best and most frequent views are from the Kilpisjärvi region, in Lapland, but the lights can sometimes be seen in the south of the country as well.

The abundance of water and the warmer weather bring the curse of the Finnish summer: the mosquitoes. These irritating creatures are not so common in towns, but are all the more voracious near lakes and marshes and in the forests, and are particularly plentiful in Lapland. Although these mosquitoes do not carry any diseases, some people have a severe reaction to their bites. If this is the case, seek advice from a pharmacist, who will recommend repellents and ointments. Some Finns swear that beer is the best repellent, but you have to drink large quantities for it to be effective! World mosquito-killing championships are held every summer, the winner being the one who kills the most, using hands only, in a given time. Finns are well practiced at this sport.

There are no polar bears in Finland, contrary to statements made in some guidebooks, but there are brown bears. Most of these are in eastern Finland, but there have been sightings as far south as the outskirts of Helsinki. They present no danger to humans, but can be very bold when they have cubs, and hungry bears are known to kill domestic animals. The ancient Finns worshiped the bear as the king of the forest, and Finnish has more than fifty words for bear—it was believed that you had to refer to it by euphemisms; otherwise the bear thought it was being called, and that was the last thing anyone wanted. Recently, a bear on the runway at Joensuu airport held up domestic flights.

Finns also worshiped the elk, or moose. Some of the earliest cave paintings depict elks, and some of the earliest decorative objects are in the shape of an elk’s head. The modern Finns hunt elk. A foreigner wishing to hunt in Finland will need to pass a hunter’s test and have the appropriate permit and a Finnish guide. All elk hunters have to wear red or orange hats to avoid shooting each other! The number of permits varies according to the elk population. These large animals are a major hazard on the roads, as are reindeer in Lapland.

There are also many wolves, again predominantly in eastern and northern Finland, but frequent sightings occur all over the country. The rarest mammal is the Saimaa seal, found in the waters near Savonlinna and Linnansaari. Wildfowl include ptarmigan and grouse, and bird migration to the Arctic regions provides bird-watchers with plenty to see in the spring and fall. The ornithologists’ paradise is Hangonniemi, the southernmost point of Finland, where the birds rest after crossing the Baltic Sea. The migration of the swans is said to have inspired the first symphony of Sibelius.

The Finnish lakes and coastal waters teem with fish. Pike, perch, and pikeperch are some of the most commonly caught freshwater fish, together with different species of salmon, including the vendace, which is caught by trawling.

Who are the Finns, and where did they come from? Finns were first mentioned by the historian Tacitus in his history of Germany, but there is very little written evidence about them before the Romans occupied the area. It is known that Finnish hunters traded furs with the Germans, who sold them to the Romans.

The migration of Finnic peoples can be traced through linguistic loans and similarities with other peoples around the eastern Baltic, along the Volga River in Russia, and all the way to the areas around the Ural Mountains, where languages related to Finnish are still spoken. There are many peoples, including the Estonians, the Ingrians, the Votyaks, and others, who share a linguistic past with the Finns. With modern DNA analysis it has been established that the Finns share around 75 percent of their genes with the Europeans of the Baltic region, and only about 25 percent of the genes come from the East or are of Asian origin. The Hungarian language is also remotely related to Finnish.

There are still many unanswered questions about the Finns and the Sami people. Did the Sami people, who now speak a language related to Finnish, speak some other language before? Who were the Battle-Axe people, and what language did they speak?

Archaeological finds would indicate that the first people—probably hunter-gatherers—arrived in Finland around 8000 BCE, some time after the end of the last Ice Age. We don’t know who these people were, or what language they spoke. The area may have been populated before then, but the glacier would have destroyed any evidence. New finds are being made, and historians may have to reassess the prehistory of the area.

The Finns moved to the area that is now Finland from the south, across the Gulf of Finland, and from the east, along the Karelian Isthmus. There was also some migration from the east coast of Sweden to the coastal areas of western and southwestern Finland along the gulf of Bothnia. The Åland Islands were also inhabited very early. All these areas are still predominantly Swedish-speaking.

There have been some very interesting prehistoric finds in Finland, including some spectacular cave and rock paintings. In addition to the archaeological finds, there are the tales of the Kalevala, which tell the story of the heroes of the North fighting battles and carrying out feats of power and intelligence.

The pagan Finns had their own gods. The chief god, Ukko, remains in the language as the word for thunder. Many place-names refer to sacrificial grounds and burial places. Modern methods of research and scientific analysis are constantly revealing more about the past.

The Vikings traveled through Finland on their long journeys to the East. The ancient trading routes still exist, mainly the Kuninkaantie, the King’s route, which passes through southern Finland from Stockholm via Turku and on to Russia. Parts of this are a heritage trail today.

More is known about Finland after the Northern Crusades reached the country. Christianity probably arrived in Sweden with Irish monks. The first crusade to Finland took place in 1155, according to legends dating from the end of the thirteenth century, led by St. Henry, the bishop of Uppsala, and King Eric of Sweden.

Papal power was extending its reach from the west; meanwhile the Orthodox faith was actively converting from the east. Sweden wanted to secure the area of Finland, not just for the Catholic Church, but also politically as its frontier toward the east. Ever since then, Finland has been between these two interest groups. The western Finns aligned with the Catholic Church, and the Karelians in the east with the Orthodox faith prevalent in Novgorod, the predecessor to the state of Russia.

Saint Henry baptizes the Finns at the spring of Kuppis, close to Turku. Painting by R.W. Ekman, 1854.

The emerging Swedish state tied Finland closer to itself, the first documentary evidence regarding Finland as a part of Sweden appearing in a papal document in 1216. Sweden built fortifications in Häme, Vyborg, and on the south coast. Vyborg Castle, built in 1293, still stands, and is now in Russia. Castles were also built in Turku and Savonlinna, both of which still stand.

In 1323, under the Treaty of Pähkinänsaari, Sweden and Novgorod divided Finland between the two kingdoms. Karelia came under Novgorod rule, and the west and south of Finland remained within Western culture and the Catholic Church as a part of the Swedish state.

Turku became the capital of the Swedish province of Finland. The Swedish legal system, taxation, and other tools of the state were established. The bishop of Turku became the spiritual leader of the country. Finns had a right to send representatives to the Diet in Sweden in the sixteenth century.

The Reformation and the Lutheran Protestant Church were established in Finland, as elsewhere in Scandinavia, in the first half of the sixteenth century. As Sweden’s power grew and expanded eastward, Finland increasingly became a battleground, and hunger and wars taxed the population. Swedish controls were tightened, and Swedes held all the high offices of state.

The glory of the Swedish empire came to an end in the Great Northern War (1700–21). Russia occupied Finland in 1714, when Swedish attention was elsewhere. Then followed the so-called period of the Great Wrath, ending in the Peace of Uusikaupunki in 1721, and southeast Finland became part of Russia. Further battles followed, and Russia’s sphere of influence pushed ever further west. There were some fledgling feelings for a Finnish state at this time, and some talk of separating Finland from Sweden. The university in Turku was the center of intellectual activity, but there was still a long way to go before Finland was ready to be a nation-state.

During the reign of Sweden’s King Gustavus III (1771–92), there were some improvements in Finland. Work started on the fortification of Viaborg, just outside Helsinki, now known as Suomenlinna. This fort has been attacked only once—by the British during the Crimean War.

This was a period of renaissance for Finland, with improvements in government and the economy, and new towns founded. Some of the officers involved in the war against Russia (1788–90) advocated separation from Sweden, but received little support for their ideas.

In the meantime, Napoleon Bonaparte was enlarging his empire in Europe. In 1807 he met Alexander I of Russia in Tilsit, in Poland. They agreed that Sweden should be coerced to join the French blockade against Great Britain, and to force Sweden’s hand Russia attacked Finland. This war (1808–9) is known as the War of Finland. The fictional description of the war by Johan Ludvig Runeberg in his narrative poem “The stories of Ensign Ståhl” inspired the Finnish romantic movement, which in turn fueled the nationalist movement of the nineteenth century. The Russians defeated the Swedes, and occupied Finland.

Tsar Alexander I was eager to secure the defenses of St. Petersburg, and it was important to have Finland as part of Russia. After the peace was agreed to in 1809, Alexander I came to Finland and opened the first session of the Finnish Diet in Porvoo. The Finns swore allegiance to Russia, and in return were allowed to keep their Lutheran faith, constitutional laws, and rights established during the Swedish reign. Finland became part of Russia as an autonomous Grand Duchy. Alexander I was a constitutional monarch, and his representative in Finland was a governor-general. The Finnish Senate was established with a four-estate Diet. For the first time, Finland had the machinery of a state. The Tsar favored a strong Finland to weaken Sweden further.

Russian Tsar Alexander I.

Helsinki became the capital of Finland, and grew rapidly. Viipuri, which had been established as a trading town during the Hanseatic League, flourished, and became the most cosmopolitan town of the Grand Duchy. It was said that many of the citizens of Viipuri were fluent in four languages—Russian, German, Swedish, and Finnish.

There was growing interest in establishing a Finnish identity. Elias Lönnrot gathered and recorded in writing the oral traditions of poetry and mythical tales of Finnish heroes, which later became, under his editorship, the Kalevala. The publication of these epic verses added to the nascent pride in the Finnish language. The subject of language went through bitter disagreements, throughout the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth, between the supporters of Swedish and those of Finnish. This language issue still has echoes in today’s Finland. Fueled by Runeberg’s patriotic poetry and by the philosophy and practical achievements of Senator Johan Vilhelm Snellman, the first Finnish-language schools were established in the 1860s. Finnish was also established in the university system as a teaching language. This in itself led to great innovation and work on the language. Words like tiede (science) and taide (art) were coined by the innovators of literary Finnish, the liberal attitude of Tsar Alexander II making these advances possible.

The Pan-Slavist movement under Tsars Alexander III and Nikolai II led to measures to diminish the rights of the Finns. Political freedoms were lost, but arts and literature flourished. The Golden Age of Finnish Art received international acclaim at the Paris World Exhibition of 1900, where Finns had their own pavilion for the first time. The composer Sibelius had become world famous, and his Finlandia the anthem of Finnish nationalists.

The turning point in the Russo-Finnish relationship came after Russia suffered heavy losses in the Russo-Japanese War. The unrest in Russia spread to Finland, and the Finnish Diet went through a radical reform. The four estates were replaced by a unicameral parliament, and universal suffrage was established, Finnish women being the first women in Europe to be granted the right to vote.

In the first decade of the twentieth century the Russian grip tightened further, and Finnish autonomy was severely restricted. In Finland, Russians were given equal rights with Finns by law, and political activity was closely monitored by the Russian authorities. Among many Finnish activists, the senator P. E. Svinhufvud was sent to Siberia. He later became president of Finland. The First World War and internal political turmoil in Russia culminated in the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the end of the power of the Tsars. In Finland the senate under the leadership of Svinhufvud made a declaration of independence on December 6, 1917. The Soviet government, led by Lenin, recognized Finland’s new independence a month later.

A bitter civil war followed in Finland. The opposing forces of the left, known as the Reds (landless rural workers and factory workers), and the right, the Whites (the aristocracy, army, and bourgeoisie), some of whom had been trained as the Jaeger battalion in Germany, fought a bitter war that left deep divisions in Finland for a long time. The Whites, led by Carl Gustav Emil Mannerheim, defeated their opponents, and a victory march was organized in Helsinki in May 1918. Mannerheim became the temporary head of state. There were some moves to establish a monarchy in Finland, but under the new constitution Finland became a republic. In 1919 K. J. Ståhlberg was elected the first president. In the same year alcohol was prohibited, and this prohibition lasted until 1932. In 1921, certain tenant workers gained the right to buy their land.

By this time Finnish culture had been further established by the continued success of Finnish arts and literature. Finns were successful at the Stockholm Olympics, with Hannes Kolehmainen winning three gold medals in running. The Finnish-language weekly Suomen Kuvalehti was founded, and the news agency Suomen Tietotoimisto was established.

In the 1920s the young republic started to establish its institutions. Education was made compulsory, and both Finnish and Swedish became official languages. National Service was started in 1922. Right-wing tendencies grew, leading to conflict with the left-wing parties, and many arrests of prominent socialist politicians followed. The right-wing Lapuan Liike movement was established in 1929.

The 1920s brought light entertainment, ranging from cinema to jazz and tango, into the country. Gramophone records sold in large numbers and the Finnish Broadcasting Company, Yleisradio, was set up. Women were allowed to join the civil service. Commercial aviation started. At the end of the decade, Finland plunged into depression following the Wall Street crash.

The 1930s saw more antisocialist measures. The right-wing “blackshirts” kidnapped the president; the unrest culminated in the so-called Mäntsälä rebellion in 1932, after which the right-wing activity was curtailed but not eradicated.

The Finnish film industry went from strength to strength. Architecture saw the seminal work of Alvar Aalto in the Viipuri Library, finished in 1935. Some of the rifts caused by the civil war were starting to mend.

The growth of the power of Germany and the looming possibility of war cast a shadow on the general air of optimism that had spread in Finland. In 1939 Frans Emil Sillanpää won the Nobel Prize for Literature, and the summer Olympics were due to be staged in Finland in 1940. The Olympic stadium was completed.

Russians wanted to establish military bases on some of the islands in the Gulf of Finland to protect Leningrad. Negotiations were long and unsuccessful. Russia attacked Finland on November 30, 1939. The short, bitter war finished on March 13, 1940. The winter was exceptionally cold, and the losses were heavy. Karelia was lost to Russia, and the Karelians were all evacuated to Finland. The peace was short-lived and the so-called Continuation War started on June 25, 1940. A truce was declared in September 1944.

Early in the Second World War, the German forces occupying Norway crossed over to Lapland in an attempt to sever Allied supply lines to Leningrad. In 1944–5, the German troops still in Lapland retreated, devastating and burning most of the country, including the capital, Rovaniemi. The Paris Peace Treaty of 1947 ordered Finland to pay heavy war reparations to the Soviet Union and to cede the Karelian Isthmus and part of Lapland to the Soviet Union. The Karelian refugees were housed all around Finland. Rationing continued until the 1950s. The return of the soldiers from the front resulted in the biggest baby boom in Finnish history in the years 1945 to 1950.

In 1948 the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance was concluded with the Soviet Union, and was discontinued only in the early 1990s, when the Soviet Union disintegrated. President Paasikivi established the so-called Paasikivi Line, which continued with his successor Urho Kekkonen. The reparations had forced the Finnish economy to undergo a regeneration and radical change. The Olympics of 1952, held in Helsinki, established Finland on the international map, and to top the success of the year the legendary Finnish beauty Armi Kuusela was crowned Miss Universe.

Finland joined the United Nations in 1955. In the same year the Nordic Council with Sweden, Denmark, and Norway was established, creating a free-trade area. In foreign policy the line of neutrality and nonalignment was actively promoted by President Kekkonen. Finland joined EFTA as an associate member and signed a free-trade agreement with the EEC.

Coca-Cola and rock and roll arrived toward the end of the 1950s. Finnish design came into world prominence with names like Tapio Wirkkala, Kaj Franck, Timo Sarpaneva, and Antti Nurmesniemi. Marimekko was founded by Armi Ratia. Alvar Aalto was a world leader in architecture. The Unknown Soldier, a pacifist novel about the war by Väinö Linna, became a huge success, and was made into a film that broke all box-office records.

Politically, the start of the 1960s saw a chilling of Finno-Soviet relations, culminating in the Note Crisis of 1961 over the nomination of one of the candidates for the presidential elections. President Kekkonen continued in office through the whole decade. The Finnish economy grew. There was monetary reform, one new mark replacing one hundred old marks. Forestry and the paper industry, together with shipbuilding and the metal industry, flourished. The baby boomers were squeezed out of the country to the cities, and Helsinki continued to grow. Finland grew closer and closer to the rest of Europe.

Culturally, the decade was marked by the blasphemy case against the novelist Hannu Salama and his description of Jesus in Juhannustanssit; the book was banned. A second television channel, TV2, started in Tampere; “Let’s Kiss,” the Finnish dance, made the world pop charts; and the Beatles and Elvis competed in popular music charts with Finnish tango. Left-wing radicalism was popular among students and artists. One of the main events of the decade was the staging of Lapualaisooppera, the musical retelling of the fascist movement of the 1930s. The University of Tampere, which became the leading university for media and social studies, was founded. The Pori Jazz Festival and the Kaustinen Folk Music Festival were started. There was a change of generations in architecture with Dipoli completed by the Pietilä husband and wife team. The comprehensive school system was adopted. The 1968 French students’ revolt reached Finland with the occupation of the Student Union House in Helsinki. The liberalization of attitudes also resulted in mid-strength beer becoming available from supermarkets and shops. Finns took to bingo, and started to travel to the Mediterranean sun on package tours. Even the language changed, with the use of the informal address, sinuttelu, replacing the formal, teitittely.

The economy moved into recession by the mid 1970s due to the global oil crisis, and migration to the cities and to Sweden continued. Finland became established in the international arena as a nonaligned, politically neutral state, though there were accusations, particularly from Germany, that Finland was under the control of the Soviet Union. “Finlandization,” as a term, came into existence. The OECD conference was held in Finland, finishing with the signing of the Helsinki agreement. In internal politics, the period was marked by the birth of many protest parties. The biggest of these was the SMP, or Suomen Maaseudun Puolue, led by Veikko Vennamo.

The national lottery came into being, and Lasse Viren won gold medals in the Munich Olympics. The first-ever rock festivals were held in Turku. The Savonlinna Opera Festival was revived by Martti Talvela. New Finnish operas were composed by Joonas Kokkonen and Aulis Sallinen.

The economy continued to grow, and went through the heady yuppie years. The Metro was built in Helsinki. Environmental issues came to the forefront, the Ministry of Environment was set up, and the Green movement became a political party. The mutual aid agreement with the Soviet Union was extended by twenty years in 1985, but it was annulled in 1992 following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Women could be ordained, but only after a long debate in the Church. Equal rights legislation came into force and a new law on surnames made it possible for women to keep their surname on marriage. Many women went back to using their maiden names, or combined their maiden and married names. The state monopoly on broadcasting came to an end, and the first commercial radio stations started up. The long-term president Urho Kekkonen died in 1986, marking the end of the postwar years.

The 1990s witnessed the economic crisis precipitated by the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of oil barter trade. A banking crisis followed in Finland, and the state had to intervene to safeguard the savings banks. Unemployment reached record levels. Finland applied to join the European Union, and a referendum was held in 1994 with 56.9 percent of Finns voting for joining and 43.1 percent voting against. The split between urban and rural Finland was marked, with urban Finland voting “yes,” and rural areas voting “no.”

The national highlight of the decade was in May 1995, when Finland won the world ice hockey championships in Stockholm. The Finnish telecommunications company Nokia led the whole world in mobile telephone technology. The Finnish economy grew very fast. Moving into the twenty-first century, Finland is becoming very well established in the European Union. There is continuing debate in Finland about the pros and cons of joining NATO.

Finland is a sovereign parliamentary republic. The original constitution came into force in July 1919, and there were no major changes until the year 2000. The constitution lays down the rules for the highest organs of the state and the constitutional rights of its citizens. The ultimate power is vested in the people, who elect 200 representatives to the Finnish parliament. These elections take place in March every four years, and the electoral system is direct and proportional. The parliament traditionally has representatives of many parties.

Finland has a strong tradition of coalition governments and consensus politics. The welfare state is on the agenda of all Finnish political parties, although there has been a push toward cuts to these programs in recent years. Women are strongly represented in the Finnish government. Since 2000, approximately half of all government ministers have been female. The prime minister is selected by the parliament in an open vote according to the revised constitution of March 2000.

Parliament House, the seat of Finnish government, Helsinki.

The presidential elections are held every six years. The maximum period for one president is two consecutive terms of office. Tarja Halonen became the first female president in March 2000. The current president, Sauli Niinistö, will hold the position until 2024 after winning reelection in 2018.

The president, together with the government, forms the Council of State. The prime minister proposes the ministerial posts, and the president officially appoints the cabinet of at least twelve, but no more than eighteen, ministers. The council of state has executive power and the parliament legislative power.

Local government elections are held every four years in the fall. Each municipal authority has a local council with extensive powers, including local taxation, hospitals, health centers, town planning, welfare, and education. The state assists local authorities from central funds. Finland has 446 local authorities, 111 of which are towns. There are plans to merge local authorities to form larger administrative areas. Regional government is divided into five regions, led by the regional governor. Åland has its own local autonomous government.

Foreign policy is led by the parliament and the president. The duties of representing Finland in international affairs are divided between the president and the prime minister under the amended constitution.

In 1999 Finnish voters elected sixteen representatives into the European Parliament for a five-year term. Finnish is an official language in the European Union. Finnish MEPs included Ari Vatanen, the 1981 world motor-rally driving champion, and Marjo Matikainen-Kallström, a many times cross-country skiing world champion. It is not unusual for sportsmen and pop stars to go into politics in Finland. Antti Kalliomäki, the Minister for Finance, is a champion pole-vaulter, Lasse Viren, the four-times Olympic gold medalist, is a member of parliament. The Minister for Culture, Tanja Karpela, was a Miss Finland.

Finns have traditionally been very active voters, but young Finns today are less interested in politics than in single-issue movements and environmental organizations. There is also an increasing number of small splinter parties, for instance parties representing old-age pensioners.

Until the early nineteenth century, Finland’s role in history was to be the battleground for supremacy between Sweden and Russia. Since its independence in 1917, Finland has clashed with the Soviet Union, but has had a peaceful coexistence with Sweden.

Estonia is regarded as a special neighbor by Finns, because of their linguistic and cultural similarities. Even though Finland shares a border with Norway, the remoteness of the border area means that there is much less contact with the Norwegians. The Sami people inhabit the area of northern Finnish Lapland, northern Norway, Sweden, and Russia, and have a Sami Council, which promotes their affairs across the whole area.

There is a love-hate relationship between the Finns and the Swedes. Finns like to tell jokes about the Swedes and the Russians. Seven hundred years of providing soldiers for the Swedish army, and of paying the Swedes heavy taxes to run the administration, left their mark. The lean years of the Finnish economy forced large numbers of Finns to move to Sweden to work. Finns were regarded as second-class citizens in the early years of this migration, but now that Sweden has large numbers of immigrants Finns are more highly regarded, and their children have integrated into Swedish society.

Sports matches between the two nations are always bitterly fought. The Finns and the Swedes get along well, though there are sometimes problems when commercial companies merge—the Swedes like a wide consultation process, while the Finns want quick decisions.

The relationship with Russia and formerly with the Soviet Union is complex. Since the breakup of the Soviet Union travel has become easier. The Orthodox monastery of Valamo in Lake Ladoga is a very popular tourist destination for Finns. There are a number of collaborative projects, including the restoration of the library in Viipuri, which is one of the early works of the Finnish functionalist architect Alvar Aalto.

Many Karelian Finns, who lost their homes in the Second World War, vehemently hate the Russians, and dream of having Karelia back. Large numbers of Karelians and many war veterans travel frequently to see their homeland or battlefields in Karelia.

Finns are starting to analyze the Soviet years more objectively, but there is still a long way to go. Many memoirs and diaries, and the opening up of the Kremlin archives, are providing rich material for historians. There is no doubt that the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s were a difficult time. Economically the Soviet Union was for Finland a huge and eager consumer market as well as a buyer of industrial machinery. The breakup of the Soviet Union plunged the Finnish economy into a downward spiral, from which it has now fully recovered. Finnish companies are once again expanding into Russian markets. On the political front, the so-called Northern Dimension, or Finland’s strategic position as a gateway from the EU to Russia, is much discussed.

There are approximately 5.5 million people living in Finland today, nearly 80 percent of whom are concentrated in urban areas. This is in stark contrast to only a century earlier, when 90 percent lived of people lived in rural areas and were engaged in agriculture. The social and economic changes as a result of urban migration have been enormous.

The average life expectancy of a Finn is eighty-two years. The demographic pyramid resembles that of most other industrial countries, with the middle-aged group predominating. The “baby boomers” of the postwar years are nearing or have entered retirement age. Nearly 86 percent of Finns belong to the Lutheran Church, and just over 1 percent to the Finnish Orthodox Church.

Finland also has a Sami population of 6,500, who speak several different dialects of the Sami language, and who traditionally herd reindeer. There are also Sami people living in northern Norway, Sweden, and Russia. Tourism is now a very important source of income. Winter tourism to Lapland has increased with trips to visit Santa Claus, who lives there, according to the Finns! Lapland is also growing in popularity as a destination for skiing and trekking.

The profile of the Sami people has been significantly raised in the last couple of decades with the Sami Parliament and the University of Lapland. Sami culture has gained in popularity, with such artists as Wimme and the folk group Angelin Tytöt singing modern versions of a traditional Sami singing style, joiku. There is also a newly found fascination with shamanism. There is an outstanding issue between the reindeer-herding Sami people and the Finnish state over landowning rights.

Only about 243,600 foreigners live in Finland, many of whom are refugees. Most foreigners have moved to Finland to work, to study, or to marry a Finn. The largest group of those with foreign backgrounds living in Finland are Estonians, followed by Russians, Iraqis, and Chinese. The refugee and migrant crisis, which began in 2015, has also had an impact. By international comparison the numbers are small, but the homogeneous Finland of old is slowly moving toward multiculturalism. The influx of new people, the increase in numbers of Finns working abroad, and the general trend of globalization are all having an effect on the Finns and Finnish culture.

Agriculture, forestry, and the construction industry provide a livelihood for a significant portion of the Finnish population, as do the electronics, paper, and energy industries. The paper industry, once Finland’s largest economic contributor, has shrunk considerably. Likewise, the pervasiveness of the electronics industry has diminished, with Nokia’s loss of its share of the cell phone market.

The recession of the early 1990s started to drive a wedge between the well-to-do and those in danger of social exclusion, including the long-term unemployed. Life was good in the heady days of the 1980s welfare state, but the cost was too high. A banking crisis and the worsening economy brought about redundancies and cutbacks in public spending. Elderly people, young families, and those in sparsely populated rural areas are among those most likely to suffer economic hardship, and there are regular soup kitchens in some deprived urban areas. Life continues to be very good for those who are employed.

Finland is a small, relatively new country, but it is known internationally for quite a few things:

• Nokia: Many people all over the world remember their first cell phone, and there is a good chance that that phone was a Nokia. The company experienced an enormous blow with the release of the iPhone and the rise of smartphones, but it is still around, still producing phones, tablets, tires, and rubber boots.

• Linux: Created by a Finn by the name of Linus Torvalds, Linux is a free and open-source computer operating system.

• Sauna: The only internationally recognized Finnish loanword.

• Finnish education: One of the things Finland is most famous for is its stellar education system. People from all over the world come to behold Finnish schools and to see what they’re doing differently.

• Finlandia: Whether the vodka brand or the soaring anthem by Jean Sibelius, you have probably heard the term “Finlandia” at some point in your life. The vodka, globally renowned, is produced using Finnish-grown barley and glacial spring water.

Helsinki, capital of Finland and “the daughter of the Baltic,” is a scenic seaside town, situated on the south coast, on the shores of the Gulf of Finland. It was known in the rest of the world by its Swedish name, Helsingfors, right up to the Second World War. The airport is 12 miles (20 km) from the city center.

Helsinki is a lively modern city and the largest in Finland with more than 650,000 inhabitants. The surrounding capital region, which includes the smaller cities of Vantaa, Espoo, and Kauniainen, is home to over 1.2 million people, more than 20 percent of the country’s population. There are many beautiful islands. The warm summers provide a perfect setting for outdoor activities, but in the bitterly cold winters, with icy winds from the open sea, people stay indoors. The Havis Amanda statue by Ville Vallgren is the symbol of the town and the focal point of many festivities.

Helsinki Cathedral overlooking the harbor of central neighborhood of Kruununhaka.

Helsinki was founded in 1550 by the King of Sweden, Gustav Wasa. For a couple of centuries it remained an insignificant town, almost dying out at one time, but the annexation of Finland by Russia saw the start of rapid growth and development. The Russian authorities wanted a capital closer to St. Petersburg, and in 1812 Helsinki became the new capital. The old capital, Turku, suffered a disastrous fire in 1827, after which the university was moved to Helsinki. The university is the largest in the country. There had also been a fire in Helsinki a few years before it became the capital, and this spurred the rebuilding of the town, in the neoclassical style, designed by Carl Ludvig Engel. The oldest part of Helsinki is the Suomenlinna fortress, built on a group of islands fifteen minutes by boat from the south harbor. Helsinki grew rapidly through the nineteenth century to become the largest city in Finland, and the twentieth-century migration from the countryside has made Helsinki and the towns surrounding it home for one in five Finns.

The architecture of Helsinki is a mixture of the neoclassical center, the Finnish national romantic style, and modern and postmodernist architecture. One of the latest landmarks is the modern art museum, Kiasma. The Olympic Stadium was built at the end of the 1930s, but, because of the Second World War, the Olympics were not held in Helsinki until 1952. Helsinki is a great ice hockey town, with the new Ice Stadium and the Hartwall Arena. All three venues are also used for pop concerts.

Helsinki has a permanent amusement park, Linnanmäki (open during the summer months only). Korkeasaari Island houses the town’s zoological gardens. Seurasaari Island is the home for a large collection of traditional Finnish wooden buildings and lots of red squirrels! In fact, for anybody interested in modern architecture there is a great deal to see. You will find guidebooks and brochures at the Helsinki City Tourist Office in the beautiful Jugendstil building not far from the famous market in the south harbor.

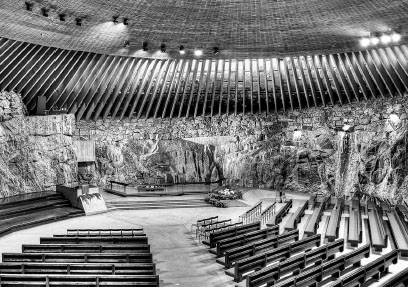

The church in Temppelinaukio, “the rock church,” is another famous landmark, together with Alvar Aalto’s last building, the Finlandia Hall, where the Conference for Security and Co-operation in Europe was held in 1975. This conference put Helsinki firmly on the international map, with the Helsinki Agreement bringing East and West closer to each other.

Helsinki has a large number of interesting museums and other places to visit. You might start by taking the number 3T tram, which takes you around the main sights.

The rock church at Temppelinaukio, situated in Helsinki’s Töölö neighborhood.

For the artistically and culturally inclined, there is a lot on offer. Some of the best Finnish art is in the national museum of Ateneum and in the many private collections that are open to the public; there are also, of course, commercial art galleries. Clubbing and eating out are excellent, and there are many annual festivals and sporting events. Check the local press for details.

It is convenient to buy a “Helsinki card” when you want to get around the town and see the sights. It comes with a guidebook, and entitles you not only to free travel on public transportation (buses, metro, trains, boats) but also to free entry to all the main tourist attractions and approximately fifty museums. It will also get you reductions on sight-seeing tours, the Finnair airport bus, car rentals, restaurants, cafés, shopping, and various sports and saunas. The card is valid for one, two, or three days. You can travel from Helsinki by boat to Stockholm and Tallinn as well as to Poland and Germany and by train to Russia.

This is the second-largest city in Finland, with about 220,000 inhabitants. Situated on the south coast, just to the west of Helsinki, Espoo has a beautiful coastline and much unspoiled natural beauty, including the Nuuksio National Park. The famous King’s Road, which connects Stockholm with Finland and Russia, runs through the town.

There is a long history to Espoo, which has its roots in prehistoric settlements from as early as 3500 BCE. The parish church dates from the fifteenth century. Espoo has as one of its centers the Tapiola garden city, which is a model for town planning for architects the world over. Today Tapiola is a leading technology center in northern Europe.

The Helsinki University of Technology is in Otaniemi, near Tapiola. The former student union building, Dipoli, is a masterpiece by Reima Pietilä and Raili Paatelainen. The campus and university buildings are by Alvar Aalto.

The organic architecture of the Dipoli building, today the main building of Aalto University, uses native Finnish materials such as pine wood, copper, and natural rock.

Vantaa, situated due north of Helsinki, is most famous as the location of the Helsinki-Vantaa Airport, which has several times been voted the best airport in the world. Many leading high-tech and logistics companies are situated around it. The Finnish science center Heureka is in Tikkurila. Ainola, the museum home of the great Finnish composer Jean Sibelius, is on Lake Tuusulanjärvi. Close to it is another interesting museum—the studio and home of the famous Finnish painter Pekka Halonen, of the Golden Age of Finnish art. There was a very lively bohemian artistic population around the lake at the turn of the twentieth century.

Tampere, 109 miles (175 km) north of Helsinki, is situated in the region of Häme, on the banks of the Tammerkoski rapids, which run between two large lakes. Founded by the Swedish King Gustav III in 1779, the town is called Tammerfors in Swedish. It was a center for the textile industry, and was one of the birthplaces of the trade union movement in Finland. During the Finnish Civil War one of the fiercest battles was fought here. Tampere is now the biggest inland town in the Nordic countries, and the second-largest regional center in Finland after the Greater Helsinki area.

Tampere has two universities, and has produced some of the most famous names in Finnish media and journalism. It is also well known as a theater town. The cathedral was designed by Lars Sonck, and its murals are by the Finnish symbolist painter Hugo Simberg. Modern art is well represented in the Sara Hilden Art Museum. The city’s main library, in the shape of an owl, is by Raili and Reima Pietilä. Lenin, the Russian leader, stayed in Tampere during his exile, and there is a museum dedicated to him. Särkänniemi Adventure Park is the most popular amusement park in Finland.

Turku’s once Catholic cathedral is today the Mother Church of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland.

Turku (Åbo in Swedish) is the oldest city in Finland, the former capital under Swedish rule, and the regional center of southwestern Finland. It is situated on the banks of the Aura River, close to the Turku archipelago, and is surrounded by beautiful countryside. The “Christmas city” of Finland, Turku hosts the special declaration of Christmas peace on December 24 and many events between November and January. In the summer the rock festival of Ruissalo brings crowds of young people to the town.

Turku has two universities, two schools of economics—one Swedish-speaking and one Finnish-speaking—and many high-tech companies. Traditionally the gateway to the west, the harbor is busy and important. Turku has always been a major commercial center, and its name, in fact, means “market place.” It has suffered many devastating fires during its long history. The castle, parts of which date from the twelfth century, and the medieval cathedral are the main sights, but there is also the handicrafts museum in the Luostarinmäki, the only street that survived the great fire of 1827. The tall ship Suomen Joutsen is anchored on the river, and is now a museum. There are many art galleries and museums, one of the most interesting being the combination of old and new in the Aboa Vetus and Ars Nova complex.

Oulu, in the north, is another important regional town. It is now a leading high-tech center with a thriving university, but its history as the most important tar port in Europe goes back four hundred years. It is the fastest-growing urban center outside the Greater Helsinki area. It is often referred to as Finland’s Silicon Valley; its technology village, Technopolis, was founded in 1982.

Further north, in Lapland, is the town of Rovaniemi. Burned down by the Germans at the end of the Second World War, it has now been completely rebuilt. The Christmas charter flights, bringing tourists to see Santa Claus, land here.

In the south of Finland the city of Lahti has become an important conference center with its new Sibelius Hall, the largest wooden building built in Finland for a hundred years and, surprisingly, the first concert hall to bear the name of Sibelius. The hall is home to the Lahti Symphony Orchestra, led by Osmo Vänskä, who has become a leading interpreter of Sibelius’s music. Lahti is also an important winter sports center, with two huge ski jumps, and is the starting point for the 100-kilometer Finlandia ski event every winter.

If you are interested in experiencing Finnish nature, yet do not want to stray too far from Helsinki, Lappeenranta is the city for you. A two-hour train ride from the capital, the city is situated on the shores of Lake Saimaa, the largest lake in Finland. Lappeenranta’s historical fortress contains Finland’s oldest Russian Orthodox church, two museums, and several cafés, and is located high on a hill, overlooking the city, the harbor, and the expansive lake. It is well worth a visit. At the harbor you can hop on a cruise ship and explore the surrounding area, or even take a three-day cruise to St. Petersburg, Russia. The cruises to Russia are visa-free.

If you are traveling in summertime, and particularly if you are traveling with children, you may enjoy visiting Lappeenranta’s famous sandcastle. Every summer, the city of Lappeenranta commissions artists from around the world to design and build a new giant sandcastle, something it has been doing since 2003.