I’ll Tell You Who Did It: My Father

or, The Private Investigation of Jan Skrodzki

Jan Skrodzki, an engineer retired from the Gdańsk shipyard, was a little boy when, from a window of his parents’ house in Radziłów, he saw Jews driven to their place of execution by Poles. When he left the town as a teenager he vowed never to return. At gatherings with family and friends he always said openly that it was locals who had burned the Jews in Radziłów. It always ended in a quarrel, but Skrodzki stubbornly went on saying that no German had held a gun to anyone’s head, and that anti-Semitism and a lust for pillage were the causes of the atrocity.

He has an astonishing memory; he talks about things that happened in his childhood as if they were still before his eyes. He describes the image he saw from behind a curtain as if looking at a photograph:

“I was six years, seven months, and fourteen days old at the time. First I saw how Jews were forced to pull up weeds in the marketplace; it was paved and weeds grew up between the stones. Then from another window I saw the column of people on Piękna Street. Later I saw plenty of film showing Jews being rounded up elsewhere. SS men, guns, dogs: there was nothing like that here. It was our people from Radziłów and the surrounding villages. They must have plotted it earlier—on such and such a day we’ll kill them—how else would they have all met up like that? It wasn’t any underclass doing it. There were a lot of young people, not with little sticks but with heavy clubs.

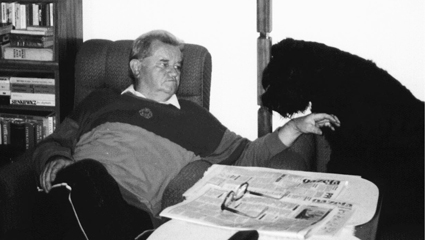

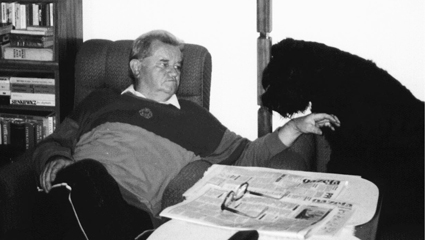

Jan Skrodzki with his dog, Czacza, at home in Gdańsk, 2002. (Courtesy of Jan Skrodzki)

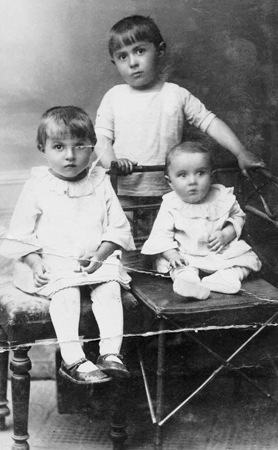

Szyma, Bencyjon, and Fruma, children of Szejna and Mosze Dorogoj. Radziłów, 1922. Bencyjon emigrated to Palestine before the war. Fruma fled as soon as the Germans entered Radziłów and survived the war in Soviet Russia. Szyma, also called Dora, was brutally murdered by Poles in July 1941. Jan Skrodzki’s father, Zygmunt, was one of the perpetrators. (Courtesy of Jose Gutstein, www.radzilow.com)

“I often hear there’s no anti-Semitism in Poland now. I always say, ‘There are a lot of anti-Semites in my family, and of the people I know, every other one, or maybe every third, is anti-Semitic, and I could easily have been, too.’ And where did we get our anti-Semitism? The priest preached it from the pulpit, that fat Father Dołęgowski. And Poles in Radziłów lapped it up because they were uneducated or completely illiterate. Envious of Jews because they were better off. While Jews were working harder, organizing their work better, supporting each other.”

Skrodzki speaks of his father with pain and respect: “He was a sought-after tailor, and he employed several skilled artisans. How is it possible that such a wise, honest man, an outstanding tailor too, could be such an anti-Semite?”

He knew that to compete with the Jews, his father opened a bakery and got an excellent baker in from nearby Tykocin, Mr. Odyniec, also a National Party member. As if that weren’t enough, he had a sign painted to say: CHRISTIAN BAKERY.

“Why Christian bakery?” Jan asks, and replies to his own question: “Just to annoy the Jews. He must have really been a good tailor, because after the war when we moved to Milanówek near Warsaw he was taken on at the Industrial Design Works, the best design institute in Poland. He was courageous, too; during the war he joined the Home Army, and he had a radio in a hiding place he’d made between the stove and the floor.

“When the amnesty was proclaimed my father appeared with his division. The guys then brought all their arms in to the station on trucks. They were naive. Two months later the authorities came for my father, they threw him in jail, and he spent nine months there before the trial took place—it was at the court in Ełk. My mother was left to take care of all the kids. I was in eighth grade at school in Łomża and I had to drop out for a year to help at home. In the meantime they started to prosecute the criminals who had killed Jews. My father was put in jail a second time. They didn’t manage to convict him for the Home Army, maybe they could get him convicted for the pogrom? Nothing was proved against him.”

It’s Skrodzki who proposed to go with me to Radziłów. He knows best who to talk to and how. He’s prepared to help me get something out of people who won’t want to talk to me, a stranger and a journalist in the bargain. And he can do his own investigating while we’re at it. He wants to find out what the people whom he remembers fondly from childhood were doing that day.

The first time we went was in February 2001. Jan was thoroughly prepared. He had a list of people who were in town in 1941, and who live in Radziłów today. And a separate list of people who participated in the murders, reconstructed from things he himself had heard as well as from Menachem Finkelsztejn’s testimony. Next to the names of people about whom there was no doubt he had put a plus, and where he wasn’t sure, a question mark.

We went by his cousins’ house. An affluent farm, well maintained, with an old Mercedes in the driveway. On the front steps, when we were already at the door, Skrodzki suddenly switched from addressing me formally as pani (Miss) to the informal ty (you): “I told them you were my cousin,” he explained. “Otherwise they won’t talk to you.”

Somehow the conversation with his cousins wouldn’t get going. The chatty Skrodzki reminisced about his childhood. How under the Soviets his father stopped sleeping at home for fear of being deported. He went into hiding, and when the news got around that families would be deported, his mother gave Jan to relatives to hide, and she found a hiding place somewhere nearby with her two youngest children.

Then our hostess spoke up: “When there’s talk about the Soviet times I always think of what used to be said around here about the Jews sending people to Siberia.”

Skrodzki protested, “With us, it was a Jew who saved our lives, because he told my mother what night the Soviets were coming for us. I was taken to the Borawski family in Trzaski on a truck. When anyone came by they hid me in the closet or the annex. There were no Jews living there, and to be quite clear, my hosts were hiding me from the Polish neighbors. If that Jew hadn’t told Mother about the deportation we wouldn’t be talking right now. Mama would have died on the way to Siberia with her three children.”

“That’s true,” his cousin admitted. “The Jews knew everything in advance because they pointed out who to deport.”

Skrodzki explained that there are bad apples among every people, and a decent Jew wouldn’t collaborate with the Soviets any more than a decent Pole.

“You’re right,” said the cousin’s wife. “When I was a cleaning lady in America, once I worked for Jews, and another time for Germans who had family pictures with people wearing swastikas. Both were decent people.”

Skrodzki tried to turn the conversation to the subject of the massacre. He started by recalling Zalewski, their uncle and an eminently decent fellow. He said he’d heard from his daughter Halina that a Jewish woman who had been beaten up by one of the Mordasiewiczes had run to the Zalewski house for help.

“That’s right,” his cousin chimed in, “because the Mordasiewiczes’ mother was deported to Siberia, with a small child. If someone’s family hadn’t been deported they wouldn’t have been there that day. Anyway, why are we talking about it, none of them is even alive anymore.”

“If you know none of the killers is alive, does that mean you know who they were?” I blurted.

“I’m not going to speak ill of the dead, especially since they’d suffered injustice.”

And that was the end of it.

We visited a number of Jan’s childhood friends. Accustomed to steering conversations myself, I had to be patient, because I was only Jan’s cousin on his wife’s side who had come along almost by accident. To visit everyone on Jan’s list would have taken many days. All the conversations went on for hours. Jan took the lead and I fidgeted restlessly, waiting for him to start asking about the massacre. After all, I thought, they must guess what brings us here. A lot was already being said and written about nearby Jedwabne.

“Do you remember,” Skrodzki asked one friend from childhood, “that my father owned the most powerful Pfaff sewing machine, and he was one of the first in Radziłów to have a Diamant bicycle?”

“Your uncle Zalewski had a Pfaff, and a Singer, too, the kind where you moved the treadle with your knee. I was a journeyman working for him then, but only your uncle used a Pfaff, and only the ablest, Antoni Mordasiewicz, was allowed to sit at it.”

I had already heard from Stanisław Ramotowski that this Mordasiewicz was not only an able journeyman but also a murderer. Yet there I was listening to them going on about sewing machines, about Henio’s sister who had her eye on Jan, and Henio who in his turn liked Władzia. They could also talk without end about postwar partisan groups, how “Groove” was killed, how Marchewka was killed. Only after exhausting these topics did Jan reveal why he had come: “I have to find out about everything, because the Institute of National Remembrance is examining the Jedwabne affair, they’re sure to come to Radziłów, and they’ll ask me about Father, so I have to be prepared. Cousin Anna, you take notes,” he tossed off in my direction, which allowed me to do so without raising suspicion.

I soon understood this tactic would get us invaluable information that I would never have gotten by myself. It was exactly this kind of conversation, this small talk about old times, that gave us that chance.

“You remember there was a guy, his nickname was Dupek [Ass],” Józef K. related. “You know, the guy who set the barn on fire, the widow’s son, Józef Klimas.”

When we talked to anyone over seventy it was hard not to wonder if he or she had taken part in the atrocity. And so when we visited Franciszek Ekstowicz, a tailor trained by Jan’s father, and I looked into this quiet man’s noble, chiseled face, I thought: No, not him, I’m sure.

Franciszek Ekstowicz had been herding cows that day and only got back to town in the early evening. I asked him if his friends who were looting abandoned houses hadn’t called on him to join them.

“I went into one house; Kozioł, the son-in-law of the Jewish woman who lived there, was an educated man and he had a lot of books. My friends took out the chairs, the table, but I took the Jew’s books. They laughed at me later: ‘Stupid guy, he took the paper.’”

When I asked him what the books were, he was quick to withdraw, as if I’d demanded restitution. A minute later, perhaps not by accident, he quoted the poets Adam Mickiewicz and Adam Asnyk. But I didn’t dare to ask him directly if those were the “post-Jewish books” that he took from Kozioł’s house.

The second day of our visit we realized Jan’s cousin must have looked in the rooms where we had slept. Remarks she made to Jan showed she had read his notes, where under the heading “probable murderers of July 7, 1941,” he had written her uncle’s name in his clear handwriting, if with a question mark. From the looks she cast in my direction I inferred she had also familiarized herself with my appointment book, in which I’d written “Call Mr. Skrodzki” several times.

We left Radziłów in the late afternoon, it was already dark, and it would have been more sensible to leave early the next day, but the atmosphere where we were staying was tense—to put it mildly. I drove on icy roads with snowdrifts. The drive to Warsaw, which usually took me three hours, this time took seven and a half.

Not long after our expedition to Radziłów, Skrodzki received a letter from his family commenting on his bringing me there: “The devil must have gotten into you, Jan.”

He sent back the copy I had given him of the historian Szymon Datner’s text “The Holocaust in Radziłów” with corrections, giving the proper spelling of names often extremely distorted in the article. There were a few ambiguous fragments in the text. The following sentence, for instance: “The first victim fell, a tailor named Skondzki, and Antoni Kostaszewski committed the bestial murder of a seventeen-year-old girl and Komsomol member, Fruma Dorogoj, saying she wasn’t worth a bullet. They cut her head off in the forest near the Kopańska settlement and threw her body in the swamp.” Reading this again, it occurred to me that the text was badly edited, that the tailor wasn’t the first victim but a perpetrator of the atrocity, along with Kosmaczewski (I already knew that was the real name. I also knew the murdered girl was in fact called Szyma, not Fruma). When Skrodzki told me his father was a tailor I wondered if there hadn’t been another confusion of names; it’s not hard to turn Skrodzki into Skondzki.

Janek must have had the same thought, because when he returned Finkelsztejn’s testimony to me with corrections, he had crossed out Skondzki and written in Skrodzki in pencil, with a question mark. Then I proposed that if he was worried about that tailor being his father, I would take him to see Stanisław Ramotowski, who is the walking memory of the massacre.

Earlier when I told Ramotowski I had visited Zygmunt Skrodzki’s son in Gdańsk and that we were planning to go to Radziłów together, he protested vehemently: “Miss Ania, you don’t want that kind of friends.” But when I came back from Radziłów and asked him directly if Skrodzki’s father was one of the killers, he clammed up. He said he hadn’t been at the barn, and how was he to know who had been there? He only knew what he saw with his own eyes, that before the war when the vicar Kamiński headed a nationalist attack squad that broke Jews’ windows, Zygmunt Skrodzki was right behind him.

“He was the best man in town for those things.” And he added: “He was an enemy of Jews.”

But when I visited him with Jan Skrodzki, he didn’t want to remember any of it.

“No, no, we’re not talking about your father, it might have been Eugeniusz Skomski, a tailor who lived across the street from the depot, he was involved,” he explained, and changed the subject to the beautifully tailored black leather jacket he still wears, and which was made for him half a century ago by Zygmunt Skrodzki.

After we left, Jan took back my copy of Finkelsztejn’s testimony with his corrections for a moment and with relief changed Skondzki to Skomski, in pen this time.

In Warsaw we visited a cousin of his, a retired seamstress living in the Praga district. The fragile seventy-three-year-old Halina Zalewska, tottering around the house, elicited sympathy from the first glance. It didn’t last, unfortunately. She knows a thing or two about Jews; she listens to the anti-Semitic ultra-right-wing Catholic Radio Maryja all day long.

She saw her Polish friends driving her Jewish friends, some pushing prams, to their deaths. She pitied the victims and railed against the killers, but at the same time she spiked her account with phrases like “dirty Jews,” “that damn parade of Soviet flunkies,” “those Jewish beggars, now they want their property back,” and blithely laid blame for the atrocity on the victims.

“Eight hundred head from Radziłów were burned. There were so many because Jews multiplied like rabbits. The Jew lorded it over us. They spread out, supported their own. Jews stopped at nothing in their efforts to impoverish Poland and keep it from developing. We put up with it for many years. There wasn’t any prejudice against Jews, Poles were just angry about what the Jews had done under Soviet rule. Jews joined the NKVD, drew up deportation lists. I remember under the Soviets how they stood at the bed at night, pointing guns: ‘Ublyudok [motherfucker], tell me where your father is hiding.’”

“Local Jews swore in Russian?” I asked to make sure.

“No, no, those were the ones who’d come from Russia. But there were plenty of locals in the police force, routine Communists and traitors to the Polish nation, the Jews Lejzor Gryngas, Nagórka, Piechota, and there was our maid Halinka’s brother-in-law, no matter what his name was—he was a Pole, not a Jew. Holy Scripture tells us the Jews are a tribe of vipers, perverts, they’re untrustworthy and faithless. They played tricks on the Lord himself, and He had to send down plagues on them. He made them wander in the wilderness for thirty years. It’s no accident He punished them the way He did. I’ve known about that from before the war, from religious studies. I remember everything, I’m seventy-three and I’ve still no sclerosis at all, though I don’t eat margarine, only butter, because it’s Jewish companies that make margarine.”

Skrodzki tried to intervene: “The Old Testament, the source of our faith, we share with the Jews, and Jesus was a Jew.”

“What are you saying, he was God’s son, that tribe has nothing to do with him. He didn’t speak much Hebrew and no Yiddish at all.”

Janek quoted her Finkelsztejn’s testimony on the tailor Skondzki, who, with Kosmaczewski, committed the bestial murder of a young girl.

“Ah, that was the daughter of the shoemaker Dorogoj, who lived near the depot. Dark hair, she wore it short,” Zalewska immediately remembered. “She threw a rock at the cross and blasphemed. I don’t say I approve of them killing her in the swamp and cutting her head off, but it should be said she was a member of the Komsomol.”

Janek asked her if his father might have been involved.

“I want to know the truth, even the worst,” he prodded. “As his son I have a right to know if my father took part in an atrocity.”

“It was a shock, but on the memory of your mother and mine, I swear no one knows what really happened. Your father was a young man and game for a fight,” his cousin said nervously. “Your father was a nationalist, it’s an honor to remind you of it. Strong young men would knock over the Jews’ barrels of herring, knock down their stalls, tell Poles not to buy from Jews. The Yids remembered your dad was an activist, that’s why they put him down for deportation.”

During our visit with Halina Zalewska I whispered for him to question her about each of the people we’d talked to in Radziłów.

“Waldek K. wasn’t involved, was he, just his brother?” Jan asked. Waldek K. was father-in-law to Jan’s cousin, the one who welcomed us on our first visit and later. “Oh, no, how could you say that, he had God in his heart. He might have done some looting, whoever was strong and happened to be around took advantage. In the marketplace that day, Father met an artisan he employed who’d come to town to take a bed from a Jewish house, because his family were so poor they slept on the floor. The only Polish people who took part in the killing all had seen members of their family deported by the Soviets.”

“So Józef K. didn’t join in?” I wanted to make sure about the brother-in-law of the friend of Jan’s we’d met in Radziłów, none of whose family had been deported; I knew that for a certainty. He was an open, sympathetic person, but I had grown suspicious when he broke into a nervous giggle a third time; each time he’d done it we had been talking about killing and raping.

“Józef took part in those pogroms of Jews, they went by houses at night. His family hadn’t been deported, he just did it for the company.”

In Otwock, just outside Warsaw, we went to see Bolesław Ciszewski, who had been Jan’s father’s tailoring assistant. He was fifteen at the time. He saw Jews driven into the marketplace and infants thrown into the burning barn. He spoke of it without compassion. Jan asked him directly whether his father had taken part.

“Your father was a tough guy and let’s not forget what the Jews had done. How many Polish families did they send to Siberia? People had reason to bear a grudge against the Jews, and now I don’t know what the Jews bear a grudge about.”

When we went back to Radziłów, we didn’t go to see Jan’s cousins again. Jan understood from their letter that relations had been severed. Instead, we headed for his childhood friend Eugenia K. and her husband. When we had been with his family the situation had been tense, but now we were met with warmth, implored to stay the night, beds had already been made up for us. And then our host started to talk: “I met your cousin in the market. He said you’d come to see him with a Jewish girl. I just shrugged and said, ‘I don’t believe Jan would soil his own nest.’ And turned my back on him.”

When we got back to the hotel I gave Jan documents to read from the 1945 trial of one of the Radziłów killers, Leon Kosmaczewski. I’d only just received them and hadn’t yet managed to look them over. My favorite detective series, Columbo, was on TV. During the commercials, Jan read me excerpts from the investigation.

Columbo said, “Now I can tell you who’s the killer.” Commercial break. Jan started reading the record of Menachem’s father Izrael Finkelsztejn’s interrogation on December 3, 1945: “Kosmaczewski got several people together in a gang and started demolishing Jewish homes. They dragged people out of their homes and beat them until they lost consciousness. They also raped a lot of young girls, special note should be taken of their rape of the Borozowieckis, mother and daughter, whom they later killed. Those night rampages went on for two weeks, until July 7, 1941.” He listed the gang members: “Skrodzki, tailor, was also one of the leaders.”

“Somehow I knew that,” Jan said. His voice was calm, but his fingers were nervously paging through the records.

With this new and bitter knowledge, he continued the search with me.

“This was a decent family,” said Jan, leading me to another house in Radziłów. “They lived on Piękna Street. Aleksander is still alive, he must have seen a lot.”

Aleksander Bargłowski was not happy to see us. He didn’t know what happened during the war, and he didn’t remember the period before the war. But when Jan began to talk about the National Party’s activities, he involuntarily began humming a song he remembered from his childhood, sung to the tune of a Kościuszko-era peasant recruits’ song:

Onward, boys, make haste,

A harvest now awaits us.

Let’s take back all trade,

Seize the Jews’ big gains.

I didn’t manage to get the second verse, he was singing it softly under his breath. When I asked him to repeat it, he seemed to realize how inappropriate it was in the context of what had happened later. He grew flustered, fell silent, and no longer remembered anything at all. Jan put a blunt question to him: “Who did it?”

“I didn’t see anything. I know it was the Germans.”

“I’ll tell you who did it: my father was one of them. Poles did it.”

A silence fell, but our interlocutor couldn’t bear it in the end. Softly, under his breath, he swore: “Fuck, you’re right, it was a foul thing that happened.”

And he started to talk.

“The day before, Jews had already hidden in the grain. They found them there and dragged them off to the barn. That day I was digging peat near Okrasin. I heard the screams, saw the smoke. The wife of the Jew Lejzor, the ragman, whose son had a big family, hid in our chicken coop. I saw her and said, ‘You just sit tight, woman.’ But later she got herself together and left. That day the postman came by, Adam Kamiński, who was in Russia during the revolution. He said, ‘Don’t go there, don’t go looting.’ Nobody from our family went, none of us laid hands on anything that didn’t belong to us. People were running over there out of curiosity. I would have been ashamed to go there, or take anything. I’d gone to school with Szlapak’s boy, his dad had a shop. And I was supposed to steal from them, from my friends? Anyway, Mother made me clothes on her loom, my aunt in America sent me things, I didn’t have to pounce on their old stuff. It was those shits from the villages, from Wąsosz and Lisy, who arrived in droves. That scum did it, and they gave all of Poland a bad name.”

When back in Warsaw, I brought Stanisław Ramotowski the documents from the trial against Leon Kosmaczewski; Ramotowski admitted seeing Zygmunt Skrodzki on the day of the massacre, standing in front of his house, and said he had to have taken part. Ramotowski hadn’t wanted to say it when he was talking to me and Jan Skrodzki, because he didn’t want to make me uncomfortable.

The next time Jan and I went to Radziłów, we tried to find Antoni O., who was mentioned in the Dziennik Bałtycki (Baltic Daily). He had witnessed Polish residents armed with sticks and clubs rounding up Jews. It turns out there is such a person, the initials fit; he lived in Radziłów throughout the war. Jan Skrodzki even remembers him a little from old times. We spoke to him in the courtyard, because even though it was cold, he didn’t ask us in. He emphatically denied he had told any journalist anything.

Evidently we were looking for a different Antoni O. This man told us, “Jews denounced Poles to the NKVD en masse. I wouldn’t say that if I hadn’t heard it with my own ears just a few days ago on the radio.”

His father-in-law hid a Jewish woman in Wąsosz (this checked out—I heard about Władysław Ładziński from Stanisław Ramotowski), and “when later [their] daughter Sabina worked for Jews in America and revealed this to them, they just worshipped her.” When I asked for further details as someone happened to be walking down the little street, Antoni instantly changed the subject.

Soon we managed to find the right Antoni O.

He was Antoni Olszewski of Gdańsk; Olszewski’s mother, Aleksandra, hid two Jewish children on the day of the massacre. She quickly moved them on, fearing retribution from her neighbors, but in the 1980s the children she saved found her and invited her to Israel with her son.

“After the war kids were sometimes told, ‘Go get some sand from the grave,’ because there was good yellow sand there for plastering. I took it from there, too,” he continued, adding that there were stones from the burned barn in the foundation of their house. “Everybody took them. Once I found a bone and threw it out in a rage, and a friend of mine threw a skull into the river. It’s so shameful when I think about it now, but then we didn’t have the imagination to realize.”

He remembered going from village to village with the volunteer firefighters orchestra to give concerts. Sometimes they heard, “You’re from Radziłów, where you burned the Jews.” No one talked about it back in Radziłów.

“Though when you bought a half liter of vodka from Strzelecka or from Bronia Pachucka, who sold vodka back then, tongues would wag. Later I knew a lot about it, because in our house it was spoken of freely. Jews had been driven into the swamps near the mill and drowned, and Mother always said, ‘Don’t go there, people were drowned there.’ When women from the neighborhood came over Mama brewed them beer, and they always ended up talking about that same thing. I remember my mother raging about one of the killers: ‘I don’t know how that shameless son of a bitch has the gall to carry the canopy in the procession.’ The mothers of those killers were hardest hit. Olek Drozdowski’s mother would come by to have a cry: ‘My dears, what could I do? He was a grown man, he once threatened to split my chest open, too.’”

Whether due to fear, complicity, or a need to forget, the killers melted back into the community.

Antoni Olszewski’s mother didn’t hesitate to send him to apprentice with one of them, Feliks Mordasiewicz.

“He taught me blacksmithing—he was a good craftsman and my dad had to sell a cow to afford to pay him,” Olszewski recalled. “A group of thugs would gather at his place to reminisce. They’d chase me away: ‘Get lost, you little shit.’ My aunt had let something slip once, I hadn’t realized what it was about at the time, so I repeated what she’d said: ‘Master, don’t those Jews ever come to you in your sleep?’ He said, ‘You son of a bitch,’ and threw a hammer at me.”

I remembered Ramotowski telling me that he went to Mordasiewicz because there wasn’t another smith who shod horses as well as he did. “But I wouldn’t look at him, or he at me; he kept his head down,” said Stanisław. It turned out Olszewski remembered those occasions: “Mordasiewicz made him blades for his mill. Ramotowski’s wife always came to town with him, but she refused to set foot in the smithy. Whenever she passed by she would stiffen and quicken her step.”

In the course of our research Skrodzki and I went back to Radziłów and its environs more than once, as well as visiting the Mazury, Kaszuby, Pomorze, and Mazowsze regions—anywhere Jan managed to find a lead. He never failed to astonish me with his skill in conducting interviews. He patiently waited for the moment when his subject had said everything he could get out of him, and then, all of a sudden, he would confront him with the truth: “Poles did it. There weren’t any Germans there.”

“But they could have been there in plainclothes!” they’d protest.

“There were none,” Skrodzki countered. “The Germans came and went. They figured out they could trust the Poles to do their work for them.”

“So that’s what happened,” said his cousin Piotr Kosmaczewski, who thought the Jews themselves were to blame.

In Grajewo we went to see Jan Jabłoński, the brother of one of Skrodzki’s childhood friends. He was ten years old in 1941, and remembered pasturing cows on the other side of the Matlak river that day. He seemed wary about speaking with us.

“The Germans did it,” he claimed.

“Did you see them?” I asked.

“It had to have been the Germans, it was during their time.”

Toward the end of our visit, in the heat of conversation, Jan Jabłoński remembered that he had been at the barn after all. There were Germans there, in blue uniforms, helmets, SS insignia. Dozens of machine guns were pointed at the barn. The Germans had blocked the gates with wheels so no one could open them, and they ordered Józef Klimaszewski at gunpoint to set fire to the barn. Then they brought chlorine or quicklime and sprinkled it around to prevent infection.

Skrodzki interrupted him: “You should tell the truth, not spout this kind of crap. If we don’t get to the truth, it will go on until it falls on the generation of our children and grandchildren.”

Jan Jabłoński admitted there were several killers. He also remembered the Poles looting. “When they came from Wąsosz, our people said, ‘Pashol von,’ Russian for ‘get out of here’—‘you’re not going to steal from our Jews.’ It’s twenty-five kilometers from Radziłów to Wąsosz. But if looters came from five miles away, they weren’t turned back.”

Jan and I tried to build a picture of what life was like in the town after the massacre. The people we talked to told us:

“They said the Germans would show their gratitude for our welcoming them and doing away with the Jews by leaving us in peace.”

“But later it was even worse than under the Soviets,” said Andrzej R.

And after the war?

“After the war everything was normal. As if there had never been any Jews,” said Jan C.

“In church there was never any mention of the massacre of the Jews. It happened and that was that,” said Bolesław Ciszewski.

“The brothers Dominik and Aleksander Drozdowski, who had both been very active in the killings, went out in the marketplace right after the liberation and set out the goods they’d looted. It was a big event, and everybody bought from them,” said Andrzej R.

We asked why nobody pointed a finger at the killers after the war.

“They were scared.”

“Why do you think, to keep the peace.”

“I’m telling you, they were scared,” Marysia Korycińska said, supporting the first speaker. “When Feliks Godlewski was drunk once, he got up and made a gesture of cutting someone’s head off with a scythe, saying, ‘A man to me is nothing more than a whistling of the air.’”

“I have to get at the truth to atone for what my father did,” Jan Skrodzki said the next time we set out in search of witnesses, this time in Pomorze and Kaszuby. He found no understanding. One subject, Andrzej R., brought a form for a contribution to the High Divinity Seminary. “Why spend all that money driving around Poland? Pay for a Mass to be said for your father and your conscience will be clear.”

In Ełk we found Leon Kosmaczewski’s family. A spacious villa on a slope right on the lake where Kosmaczewski’s daughter and twenty-year-old granddaughter live; he himself died two years before, at the age of eighty-eight. He was in good health to the end. They had no intention of talking to us, but Skrodzki gave them no chance to throw us out, saying his mother’s maiden name was Kosmaczewska, so that as a child he had called all Kosmaczewskis “Uncle.”

“They accused him of raping a Jewish woman in the marketplace, but he saved a Jewish woman,” his daughter shrieked. “A German asked him, pointing at the woman, ‘Jude?’ and he said no, and allowed her to escape. A few years later a Jewish woman turned up in town asking about him, I’m sure it was the one he saved, wanting to thank him. We know Father stood trial, but that trial was started by a vicious rumor. He had been denounced because of a deal gone wrong, a woman from the neighborhood had a feud with Father.”

The granddaughter chimed in, “Granny said Grandfather saved a Jewish woman from Kramarzewo, and now they just write anything. There’s one historian you can take seriously, Professor Strzembosz. We’re not going to listen to any nonsense from anybody else.”

Skrodzki and I both knew the Jewish woman from Kramarzewo could only have been Marianna Ramotowska. We also knew she had given false evidence in his defense in court because she feared for her life.

Skrodzki tried to cut her off, but he is a mild man, and the woman kept raising her angry voice. Finally, he got up from his chair.

“I’m not going to listen to this. The responsibility falls on us, their children. If you can’t acknowledge it, so much the worse for you. Anna, let’s go!”

And we left.

Janek seems like a content person. He has made a success of his life, was the only one of six siblings to get a higher education. He became a recognized professional engineer. He sent his two daughters to medical school. When he had to join the Communist Party in the sixties, he joined, and as soon as he could leave after 1980, he left. He greeted Solidarity with relief, as did many party members. He sang in the Solidarity choir at the Church of St. Brigid in Gdańsk. He values order and discipline. He likes getting to the train station early and planning his time so that he never has to rush. He thinks punishment is a necessary part of raising children. He loves talking about his dog, about sailing. He likes to tell jokes. I would like to understand why he of all people, an “ordinary Pole,” decided to carry the burden of memory throughout his life.