Design writers groping for gravitas are fond of quoting Roland Barthes’s comment that cars are the ‘exact equivalent of the great Gothic cathedrals … the supreme creation of an era, conceived with passion by unknown artists’. The French phenomenologist’s later comment that the display of the DS at motor shows represents ‘the very essence of petit-bourgeois advancement’ is less well known, however. Nevertheless, it is more helpful, and more interesting, to comprehend the DS in its historical context – as the very essence of the French postwar technocratic spirit. This was a time when the polytechniciens, iron-grey hair cut en brosse, were rebuilding French pride with the atomic power project, jet planes and high-rise blocks.

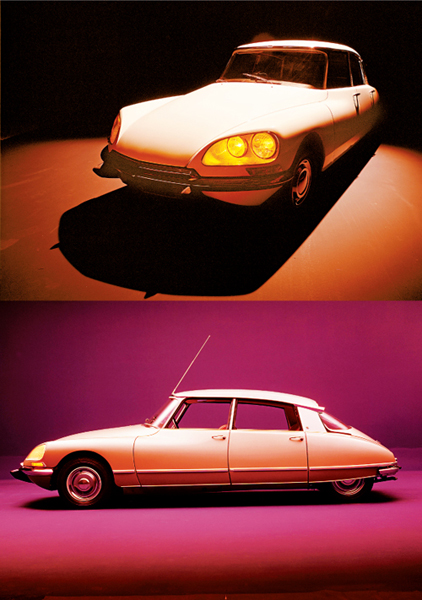

The new Citroën project was launched with Pierre Boulanger’s brief to ‘study all possibilities, including the impossible’. The car was to be ‘the world’s best, most beautiful, most comfortable and most advanced … a masterpiece, to show the world and the US car factories in particular, that Citroën and France could develop the ultimate vehicle’. The extraordinary glazing pattern, the entirely original profile and combination of body planes, the high-level indicators coming out of the roof gutter – a feature that could have gone so wrong! – the headlamps swivelling as you steered: all pronounced that this was, indeed, an inimitable car.

Technical leader was André Lefèbvre (1894–1963) with styling input from house Citroën designer Flaminio Bertoni (1903–64). However, the greatest technical innovation in the car was the creation of hydraulic suspension by the visionary engineer Paul Magès (1908–99), who replaced the conventional springs with a self-levelling and adaptive system of hydraulic struts supplied by an engine-driven pump. Magès used the same high-pressure hydraulic system to power the steering and brakes, creating a car that felt like no other, needing only the gentlest fingertip control on the wheel to avoid slaloming onto the wrong side of the road, and a brake pedal – just a button really – so sensitive that it felt like an on/off switch. Not all drivers liked the extreme sensitivity of these controls but the Citroën response, in effect, was, ‘This is the future; this is how a car should be. Get used to it!’ Some drivers never could, but for many it seemed quite perfect.

Citroën designer Flaminio Bertoni had an extraordinary achievement with the DS. It was all the more impressive because, unlike at Ferrari or Jaguar, there were no predecessors to allow designers and modellers to perfect its new form language. The DS sprang fully formed into the world.