Roger Allam

on

Falstaff

Opened at Shakespeare’s Globe, London on 14 July 2010

Directed by Dominic Dromgoole

Designed by Jonathan Fensome

With Oliver Cotton as Henry IV, Sam Crane as Hotspur, William Gaunt as Shallow, Barbara Marten as Mistress Quickly, and Jamie Parker as Prince Hal

![]()

Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2 were first performed in 1596–8, the source material coming mainly from Holinshed’s Chronicles. Many people consider them to be among Shakespeare’s very finest plays. With their astonishing breadth of scope they are outstanding examples of his genius for juxtaposing diverse dramatic elements. King and commoner, poetry and prose, town and country, war and peace, political strategy and the rumbustious low-life comedy of the tavern – all blend seamlessly into a rich dramatic entity.

The two plays can stand alone or as integral parts of Shakespeare’s cycle of eight English history plays, beginning with the deposition of Richard II in 1399, spanning the Wars of the Roses, and culminating with the death of Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. The Royal Shakespeare Company was the first to perform all eight plays, under the umbrella title The Wars of the Roses, in 1964.

It is interesting to view them in the wider context, both for their historical sweep and for the development of characters. The two parts of Henry IV reverberate backwards to Richard II and forwards to Henry V, most notably in the theme of Bolingbroke’s usurpation of the crown. His remorse sets in the moment after Richard II’s assassination. That play concludes with Boling-broke announcing ‘I’ll make a voyage to the Holy Land / To wash this blood off from my guilty hand’ [5.6]. The vein runs through both parts of Henry IV and it is echoed by Henry V in his prayer before the Battle of Agincourt: ‘Not today, O Lord, / O not today, think not upon the fault / My father made in compassing the crown’ [4.1].

King Henry IV himself is hardly recognisable from the vigorous, confident and astute Bolingbroke of Richard II. Over the two plays he becomes increasingly frail and fretful, sleepless and haunted by his sin. He eventually dies, as sick in soul as in body. Conversely the upwardly mobile Prince Hal sheds his youthful playboy image, ruthlessly rejects Falstaff, and evolves into the dashing and heroic King Henry V.

Bestriding the action, literally like a colossus, is Sir John Falstaff. He is old, grossly fat, disgraced and totally unscrupulous. He eats, drinks, lies and steals, suffers from verbal diarrhoea and celebrates his way through life… when not snoring. He towers over both plays and is arguably the best loved and most colourful of all Shakespeare’s great characters. He appeals as rogue, wit, anarchist, reprobate, life force, raconteur, bon viveur, philosopher. Even his cowardice is endearing. His final rejection by Prince Hal ends Part 2 on an almost unbearably harsh note: ‘I know thee not, old man. Fall to thy prayers. / How ill white hairs become a fool and jester!’ [5.5]. However, such was his popularity that, according to legend, Queen Elizabeth begged Shakespeare to bring him back, resulting in The Merry Wives of Windsor. The critic A.C. Bradley wrote ‘In Falstaff, Shakespeare overshot his mark. He created so extraordinary a being, and fixed him so firmly on his intellectual throne, that when he sought to dethrone him he could not.’

Both plays have large casts with a wide diversity of characters. Opposing the Lancastrian King Henry IV and his army are the Yorkist rebels led by Harry Hotspur, an individual so fiery and charismatic that young leading actors have often chosen to play him rather than Prince Hal. The dotty old justices Shallow and Silence, reminiscing in their Gloucestershire orchard, are glorious original creations. There is also a gallery of colourful smaller roles. Francis the tavern drawer who says little but ‘Anon, anon, sir!’ can be fun to play, as can Falstaff’s country bumpkin army recruits. My only involvement in the Henrys was as the warriorlike Earl of Douglas in an undergraduate production with the Cambridge Marlowe Society. As a fresh-faced nineteen-year-old from Devonshire, I was ill-equipped to play the ‘hot termagant Scot’ [5.4]. I wore a ginger wig and big bristling beard in an effort to look butch and fearsome, and struggled with the accent. The director John Barton did his best to squeeze highland ferocity out of me. We worked tirelessly until the line ‘Another King? They grow like Hydra’s heads!’ came out, as I recall, something like ‘Yanitherrr Kung? Tha-grrroo-lak Heedrrra’s heeds!’

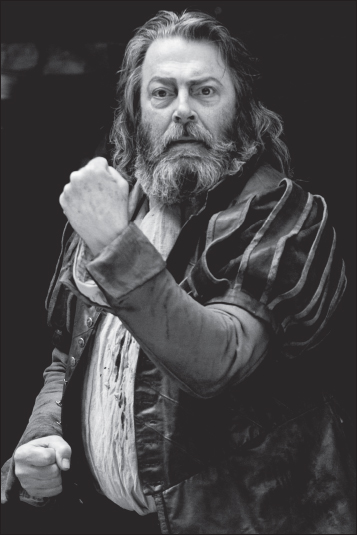

Roger Allam had a huge success when he played Falstaff at Shakespeare’s Globe in 2010. His performance won that year’s Laurence Olivier Award for Best Actor. I interviewed him at his home in South-West London the following year. I discovered that Roger is not only a superb actor but a fine cook, who effortlessly rustled up a very tasty lunch before our talk.

![]()

Julian Curry: You’ve done a lot of Shakespeare. How do you rate these two plays?

Roger Allam: They’re amongst the very finest, I would say, some people think the finest. You get such a broad canvas, with a wonderfully complete picture of England: the court and the countryside, the rebels, the aristocracy and the low life of the tavern. Even the smallest parts are written with reality and humanity, they’re magnificent. And the Shallow and Silence scenes in Part 2 are almost Chekhovian.

What was it like working at the Globe?

I’d been one of those people who was instinctively against it, I guess due to having spent a long time with the RSC, where they became quite neurotic about the Globe.

Why was that?

There was the notion of it being kind of ‘thatched cottage’ Shakespeare – I remember that phrase being used – and anti-intellectual. I suppose the same kind of suspicion happened in music when it became fashionable to play authentic period instruments. So I wasn’t enormously sympathetic to it as an idea. I went to something in the first season that I thought was utterly awful and confirmed all my prejudices against the Globe, and I never went again. In retrospect that was rather foolish, because I missed a lot of Mark Rylance’s work, which I now wish I’d seen. I didn’t go again until the year before I played Falstaff, when I saw a friend of mine in Trevor Griffiths’s play [A New World] about Tom Paine. And I was very impressed, particularly with the audience they’d built up. This slightly rambling play, which I think had been adapted from a film script, was packed with 1,500 people watching it.

That’s the capacity of the Globe?

Yeah. And they were really lively. I thought: My God, if you put this play on in the Olivier auditorium at the National it would empty the place. One of the things Dominic Dromgoole has done tremendously well is to start commissioning and encouraging authors to write for that space, to build up a repertoire.

So they do other work besides Shakespeare?

Well, they do at least one, possibly two new plays a year. It’s brilliant, because it means writers can have quite a large cast, which they don’t often get at other addresses. It stops the place becoming purely a Shakespeare house. And it helps writers, I suppose, to examine a more Shakespearean style.

There’s no artificial lighting, so you have to perform in daylight. Was that a problem?

No, actually, no. It’s something you get used to. Of course it means you can’t achieve all the effects you can in other theatres, such as standing in a spotlight surrounded by darkness doing your soliloquy. But you’re always engaging with the audience. After seeing that Trevor Griffiths play, when they offered me Falstaff I realised it’s the perfect part to play there, because he never stops talking to the audience. Another great thing about the Globe is that you can get in for a fiver if you’re prepared to stand, and that’s half of the house. Seven hundred people pay five pounds. There’s no other theatre like that in the land. You get a totally different feel when there are seven hundred enthusiasts. Well, of course they’re not necessarily all enthusiasts, because the other great thing about it only costing five pounds is that people who might not be normal theatregoers can think: Well, I’ll just pop in and see whether it’s any good or not, and I can bugger off if I don’t like it! And that’s wonderful. I’ve quite frequently kept my seat in the stalls because I’ve thought: This has cost me fifty quid, so I’ve got to stay! The only drawback to that theatre is the placement of the pillars, which are a permanent fixture. There’s nowhere you can stand on the stage where every single person in the audience can see you. Absolutely nowhere. So really, I guess, the pillars should be six or eight feet further upstage.

What was the weather like during your production?

We were quite lucky, we only had two really bad days. There was one afternoon when Ian McKellen came to see Part 1, and it just rained and rained and rained from beginning to end. Amazingly there were still two hundred groundlings, as they’re called, in the pit.

Was that the time when you segued into King Lear’s ‘Blow winds and crack your cheeks’?

No, that was the press show, which was also torrential.

A part which spans two plays is quite a luxury, isn’t it? Gives you a longer journey.

Yes, I guess so. Actually you’re not so much aware of that because you just think: Well, there’s Part 1 and then there’s Part 2, which is such a different beast. Part 1 has a natural momentum that Part 2 lacks.

Did you rehearse both plays at once, or singly?

At first we rehearsed both at once, then we left Part 2 alone and got Part 1 ready to open. While we were previewing Part 1 we went back to rehearsing Part 2, and got that ready to preview. So we’d done some performances of both, and then we went back to Part 1 and got used to doing the two together.

Did you open both parts on the same day?

Yes, for the press.

You were directed by Dominic Dromgoole. How did he work?

He’s extremely knowledgeable about Shakespeare, and he’s passionate about the Globe. He was very keen on the history of the Mummers, which have lots of links to these plays. He has a wonderful sense of anarchy and fun, but also authority, so he runs a very good rehearsal room. I guess we just did the usual thing: we sat round and talked quite a bit, and then we got the plays up on their feet and started working on them. He was very open to suggestions, which is always nice, but also good about saying: Hang on, you don’t really want to do that, do you? Which we all need at times!

Was the text more or less complete?

No. We were always looking for cuts, and I was very willing because, my God, Falstaff goes on! The part’s a monster. I don’t know how much of the text we performed, but certainly some of the monologues were cut quite a lot. One of the unexpected perks of working there, having thought that it was an anti-intellectual place, is that they have a whole department of scholarship focusing on the history of the Globe, and which actors might have played the parts first.

In Shakespeare’s company, originally?

Yes. Which can lead to certain clues. I found a book about Shakespeare’s clowns in the library, which is terribly interesting about their development coming out of the Tudor interludes, and Tarlton. The author is convinced that the first actor to play Falstaff was Will Kempe, who was immensely famous at the time. It would have been like having Tommy Cooper playing Falstaff, some really beloved comic, or Eric Morecambe. And indeed a lot of the writing of the part is like a brilliant homage to the improvisatory style of a stand-up comic. The book examines those notions very well.

I think of Kempe as more of a lightweight. He was also famous as a dancer, wasn’t he?

Yes, but he was a big man. I found that resource very stimulating. There’s plenty of information about what it must have been like round there when London Bridge was the only way over the Thames, and executed heads were stuck on spikes above the bridge. There’s a little row of houses next to the Globe, charming houses, one of them with a blue plaque saying it was built by Christopher Wren to use while he organised the rebuilding of St Paul’s. Next to it is an alleyway called Cardinal Cap Alley. I thought: How delightful – so I went down it, and you can see into the gardens of the houses. The following day I was looking in a book called Filthy Shakespeare (which is extremely entertaining) by a woman called Pauline Kiernan. She manages to find filth on more or less every page. And she says Cardinal’s Cap was a brothel near the Globe. It was run by the wife of Edward Alleyn the actor, on rented land that was owned by the bishops of Winchester.

The whores wore long white gloves and were known as ‘Winchester geese’, isn’t that so?

‘Winchester geese’, that’s right. A Cardinal’s Cap is also an Elizabethan slang term for an erect penis. So you can imagine punters saying to each other: ‘King Lear’s boring, let’s hop out and go down to The Stiff Cock for a shag.’ You start thinking about all sorts of aspects of life in that part of London when the plays were first done.

Tell me about the sets and costumes.

It was done in period. In Mark [Rylance]’s time there used to be a rule, I believe, that you had to be able to pack up every show into a single skip. You tend to get less of that now, depending on the director. But rather wonderful, I think, because with easier changeovers they can do twelve or fourteen shows a week, and that’s how the place runs economically. I think over the season I was there, they probably had about five different companies of actors.

One skip containing all the sets and costumes?

Well, not any longer. It was one skip for the costumes and another for the set and props. But you couldn’t do that any more, because they now tend to build more elaborate sets. And we had the stage built out a bit, with steps going down into the yard.

The yard is another name for the pit, where the groundlings stand who pay five pounds, is that right?

Yes. There’s also an upper level that we could use. It gave a sense of vertical space for the tavern, which was very good.

So the tavern was on the upper level?

No, no. The tavern was mainly on the ground, but at times we could go down some steps into the yard, or upstairs. And you could also go down under the stage through a trapdoor. There was a sense, therefore, that the tavern was on many levels. We went along and had an illegal rehearsal one afternoon in that old pub, The Cheshire Cheese on Fleet Street. It was originally built after the Great Fire as an inn to house the builders. The place is an absolute warren, with all sorts of upper and lower levels, rooms leading off other rooms, and so forth. I suppose our setting was a gesture towards that.

Why was the rehearsal illegal?

Because we didn’t ask permission.

Oh I see. You just went along and had a pint, and then did some rehearsal.

Had a sandwich and a pint and worked on the play.

Of all Shakespeare’s actorly characters, Falstaff must be the biggest ham of the lot, and he certainly kissed the Blarney Stone. Most have a good relationship with the audience, but at the Globe it was extra special. Did you get much feedback?

Not a lot. They’re very lively, but pretty well behaved. There was one occasion when I said to Hal in the tavern ‘If I tell you a lie, spit in my face and call me horse.’ And three girls who’d been to see the play several times shouted ‘Spit in his face!!’ [Laughs.] But that happened very rarely.

There aren’t many biographical clues to Falstaff’s past in the text. Hints perhaps, rather than clues. How did you prepare? I’m daunted looking at that huge stack of books.

Well, I just brought them down to remind me. Preparation always depends on how long you’ve got, which I can’t quite remember. I rang my friend Simon Callow and he sent me a number of books on Falstaff that were very useful. But I tend to prepare in quite a haphazard way. I don’t read these books from cover to cover; there’s so much written about Falstaff, so I tend to dip into them for stimulation. The character was originally called Sir John Oldcastle, but pressure was put on Shakespeare to change the name. Oldcastle was burnt as a Protestant martyr. He was a friend of Henry V, but allegedly rebelled against him at one stage. I believe Dominic Dromgoole found somewhere that at this rebellion, which was really half-arsed, they were disguised as Mummers. I don’t know whether that’s apocryphal or not, but I like to imagine it’s true. It was interesting to think of him as a character who embodies a mythic ‘olde England’. Now this is remarkable: Morgann’s Dramatic Character of Falstaff is a whole book written in the eighteenth century defending Falstaff against the accusation of cowardice. A whole book! I then read in Harold Bloom’s book a brief description of Ralph Richardson’s Falstaff, which he played in 1945, talking about the ‘old soldier’ element, the weariness of war. So I thought about that as well. Roderick Marshall’s Falstaff: The Archetypal Myth is terribly useful. He examines other cultures where there’s a figure who’s often fat, and a sort of a tutor. Here’s what Marshall says… [Reading.] ‘A grotesque fat, feral, oversexed, crapulous, witty, profane, old/young creature in times of trouble undertakes to misrule/rule a waste country, and educate the heir of its sick and dying monarch in practices calculated to restore peace and prosperity. But when the prince has learned his lessons, usually two battles are fought. In the first of these the tutor buffoon, with a following of bizarre recruits, helps the prince to win a notable victory over demonically powerful adversaries. After this victory the prince is crowned, the teacher rejected, imprisoned and sometimes killed. Following the tutor’s death the king, now fully initiated into the exercise of superhuman powers, goes on to win the second battle in his own right and establish joy and fertility in his kingdom.’

Isn’t it interesting how little Shakespeare actually invented, and how much he recycled!

Yes. Well, he’s saying that Falstaff, whether consciously or not in Shakespeare’s mind, has similarities with many characters in other cultures where this story is examined. Silenus, the tutor of Dionysus, for instance. The wizard Merlin, King Arthur’s tutor. Krishna, the Bhagavad Gita instructor.

So it’s an extrapolation from various similar relationships.

He’s saying that Falstaff takes his place in this mythological strand, if you like. So the research was tremendously stimulating. And it took me outwards into something very different from the usual, more psychological readings. Of course, working at the Globe, it’s not that you’re going to eschew psychology. But it’s, perhaps, not at the top of the list. Graham Holderness’s book Shakespeare: The Histories is very good as well. He talks about the carnivalising imagination, a world where a chivalric medieval prince could meet a band of sixteenth-century soldiers led by a figure from immemorial carnival. I’d never thought of Falstaff as a creature of carnival, either. Listen to this. [Reading.] ‘He wears heavy straw padding in his gut and shoulders, and a mask with teeth and whiskers. His beard is daubed red and he sometimes has a calf’s tail. Like Vice in the morality plays he carries a lath, a sort of cane, with which he beats people. He has a rout of followers with names like Johnny Jack, Little Wit, John Finney, Little Devil Doubt. And he has one called Old Tossit who, Bardolph-like, spends all his time drinking until his nose looks like a ball of fire.’

These go back centuries before Falstaff.

Yes. So the first audiences must have been aware of them, if only subliminally. Falstaff would have been part of those traditions. He was an incredibly sophisticated creation, but with a lot of referring back to earlier popular culture.

Did you beg, borrow or steal from other Falstaffs?

I’m not consciously aware of stealing. But I obviously thought about Falstaffs I’d seen in the past, especially about him being an old soldier which, as I said, Richardson was very informed by. There were various signposts. Things I did nick, or was influenced by, were not necessarily from other Falstaffs. Around that time Mark Rylance did Jerusalem by Jez Butterworth, which was absolutely wonderful. Reviewers said Mark’s was a Falstaffian character, and indeed that play is also consciously tapping into a kind of mythological olde England. Seeing it I thought: Aha, maybe that’s the way to go. It led me to imagining Falstaff for a while as a kind of Pied Piper, playing lots of musical instruments. Well, of course that’s completely impractical, you can’t do it. [Laughs.] But it did help to get some music into the play, and we used a very old folk song in the tavern called ‘Hal-an-Tow’.

You played the mandolin at one point, is that right?

It wasn’t a mandolin, it was an Elizabethan cittern. Then late one night while we were still rehearsing, I saw a repeat of Sharpe on the telly, Napoleonic war stuff starring Sean Bean. Pete Postlethwaite was brilliant as a wonderfully vile, horrible and weird character. There’s one scene where the army’s charging up a hill, very boldly and bravely trying to take a town from the French. Postleth-waite gets down under some dead bodies and pulls them over him, and hides and survives. I thought: Oh, that’s good, that’s really good. It influenced the scene when Falstaff pretends to die, which I wanted to make as convincing as possible. So then I thought maybe he carries a little bottle of blood around with him. Again, Dominic had this idea that he should eat all the time. It seemed perfect, to be constantly snacking. But of course you can’t really do that because he talks such a lot he’s barely got time to drink, let alone eat. However, we looked for opportunities, and I thought maybe when he goes to war he’s got a belt with various goodies. A cup for his sack would be nice. And, wondering what he might have with him, I looked at a book called Food in History. They’d sometimes take little treats like potted meat. Food preservation didn’t change much for thousands of years, they either salted it, dried it or pickled it. The Elizabethans had a thing which they boiled down into kind of a hard, biscuity Marmite, like stock cubes. Add boiling water and you’d have soup. So there was a bit of that in my belt, along with the fake blood and the potted meat.

This was when you were going out soldiering?

Yes. It was very much about the soldier surviving, by way of Ralph Richardson and Pete Postlethwaite.

Falstaff is a debauched old coward, an impudent braggart, a vain and drunken hypocritical liar, and he’s morbidly obese. So why do we love him so much?

I think the reason we love him so much, and Hal loves him, is that he’s fun. I was very much exercised by the notion that they should have a good time together – otherwise why is Hal with him? He doesn’t need to be. In certain ways Falstaff’s a bit like a child, an infant who does the first thing that comes into his head. For instance, I don’t think there’s a plan to deprive Hal of the honour of killing Hotspur, it’s just there. He makes stuff up, and then almost believes it. Gets carried away, like when he’s recounting the Gad’s Hill robbery.

He’s got quite a cruel streak, hasn’t he?

I don’t think it’s real cruelty. But he does treat people appallingly.

Bardolph and the Hostess seem to get the worst of it.

Bardolph gives as good as he gets. But then Bardolph is a man of fewer words, thank God – otherwise the play would go on forever!

Describe your costume, beard and wig.

I had my own beard, I grew one of immense proportions. My hair was long and they added a piece to it, and put some white in the beard. That made my head look enormous.

How fat were you, on a Falstaffian scale of one to ten?

We tried various paddings and I reckon I was pretty fat, although some people thought not enough. There was a problem that my armour squashed the fatness in, so when I put it on I looked rather thinner than, perhaps, I would have wished. With the armour off I was pretty big, but also energetic. We thought: Well, yes, Falstaff is big and fat, but he goes on long marches with the soldiers. So he’s not without energy.

At one point he says he can’t move ten yards without collapsing in a pool of sweat.

He goes off on one. He exaggerates. He’s already got to Gad’s Hill and someone’s nicked his horse and it’s pitch black. I’m not saying he isn’t big, it’s just that I don’t think he’s someone who can’t move about at all, because he does go to the war and he can draw a sword and defend himself if pushed.

The entire part is in prose. Why do you think Shakespeare did that?

Well, the clown’s part was always written in prose, which can add to the belief that Kempe played it. It’s the greatest clown’s part ever written. Prose is also a contrast to the more formal verse of the court. It puts him more in touch with the world of ordinary people.

Falstaff is very well read, isn’t he. He quotes the Bible, and Galen, and he knows the law. He may be a clown, but he’s nobody’s fool.

I’m not sure whether he actually read Galen, but he knows his Bible.

I can easily imagine Hamlet by himself, taking the character out of the context of the play. But I don’t know about Falstaff. What do you suppose he would do without company?

Talk to the audience! Hamlet by himself could read a book, whereas Falstaff would talk to the audience, whether they were there or not, because it’s through talk that he exists.

You were saying that you played the cittern.

Yes. I asked Claire van Kampen, who did our music, what instruments they might have played in the pub. And she suggested the cittern. Apparently there were a lot of them in barbers’ shops. They had flat backs so you could hang them up on a peg neatly against the wall. They were tuned a bit like a ukulele, except in a different order. So I bought a ukulele and retuned it like a cittern.

When did you play it?

We went into ‘Hal-an-Tow’ in the pub as a celebration of the fact that Hal still had the money. It was between that section and going into the mock-King scene [2.4].

You pissed into a pint-pot at one stage?

Yes. Well, no. It was a proper pot, not anything you drink from.

Is Falstaff an alcoholic? Do we ever see him drunk? Do we ever see him sober? Or is he always somewhere in between?

Probably somewhere in between. He’s never incapable. I suppose the drink helps him go further into flights of fancy. He never loses the ability to talk incredibly wittily. Shakespeare’s contemporary, the playwright Robert Greene, is considered by some to be another possible model for him. He was a famous drunk.

Reviews mentioned your ‘ripe, roguish charisma’. On the other hand, another Falstaff was described as ‘draining the bitter dregs of life’. Did you show much of that side of the character?

I think he goes that way in Part 2, where there is a vein of melancholy. In Part 1 he is more like certain people one can think of – indeed some in our own profession – who seem to stay stuck in their youth, going on hard drinking and whatever when they’re way too old. As Part 2 develops he has more intimations of mortality. The tavern scene in Part 2 has a very different, a less joyous tone to it, than the one in Part 1.

Your Falstaff was also described as a ‘dangerously manipulative operator’. Does that ring a bell?

I’m not sure that he really has a developed plan. He’s not like Richard III, he’s not like Rupert Murdoch. I imagine Rupert Murdoch, until recently at least, woke up every morning thinking: How much more of the world can I get today? Obviously somewhere in Falstaff’s mind is the notion that Hal can be useful, and when he becomes King it’ll be great. He often mentions the sum of a thousand pounds. It’s like: If only I had a grand; if I could just get a grand, I’d be fine. I often think like that as well. If I had a million, just one – or let’s say five, to be on the safe side – then I could relax; I’d have enough for my old age. That comes up very much in relation to Shallow. What’s the line about how thin he was?

‘When ’a was naked, he was for all the world like a forked radish… yet lecherous as a monkey, and the whores called him mandrake’ [Part 2, 3.2].

That’s it, always ‘called him mandrake’. And now he’s become a squire, now he has land and beefs. Whereas Falstaff has reached a point in his life where he can’t believe that he’s still basically just living off his wits.

Okay, let’s start moving through the play. Act 1, Scene 2. Your first scene opened with Hal doing up his pants after a night with Doll Tearsheet. What’s Falstaff doing?

I was just asleep.

Where are you and what time is it?

We’re waking up in the morning at Hal’s place. I guess we’re in the Palace, unless Hal has rooms in the City or somewhere. We’re certainly not in the pub.

One critic wrote that ‘Allam and [Jamie] Parker play off each other with joyous ease’. Tell me about Falstaff’s relationship with Hal. He seems to be half surrogate father, and half naughty little boy himself.

Well, yes. Another thing that struck me was that, actually, Hal learns a lot about paternal care, in a sense looks after Falstaff. He gets him out of trouble constantly, more than the other way round. But Hal sees a whole other side of life through Falstaff and meets people he wouldn’t otherwise have met – all the tavern folk, for example.

How much is it genuine affection, and how much is it greed and social ambition, that makes Falstaff bond with Hal?

I think they’re difficult to disentangle.

Are they?

Yes. I say he hasn’t got a plan, but obviously it would be a fine thing if he could get his grand – maybe a bit more – and with luck he could in future become the most powerful man in the land. In that first scene there’s a thought that he might be made a judge. But Falstaff isn’t getting much benefit from Hal at the moment…

He does pick up the tab.

Yes. Hal picks up the tab – of course you’re right. And I guess that first scene is something of a staging-post in Falstaff’s influence over Hal, to get him to agree to take part in a robbery.

In Part 2 Poins tells Hal that he has been ‘engraffed to Falstaff’ [2.2]. I’m curious to know what else there is in it for Hal, beyond enlarging his horizons.

Enjoyment. It’s difficult, I suppose, for someone rich and powerful to know how much anyone else is a true friend, and how much they’re a friend because you’re rich and powerful. But there’s genuine enjoyment. And I suppose (to get more psychological about it) you could say that Hal can attack his father through Falstaff, by being with him instead of with his father, and also by insulting and being viciously rude to Falstaff. But that’s something we might have a different take on, because there was a style of affectionate insult that was current for Elizabethans at the time. A certain word was in vogue – I think it’s mentioned in our programme. There was a group of people who would trade in it. You see that today, when actors get together, and greet each other fondly with ‘How are you, you old cunt!’

That’s very much Falstaff’s mode, isn’t it, to attack the people who are dearest to him. So they obviously enjoy each other’s company and fool around together a lot. But the first scene seems to have a shadow over it. There are hanging references, and Falstaff changes the subject. How serious is that?

I don’t think Hal is threatening Falstaff, saying: I’m going to hang you. But there’s gallows humour in the fact that Falstaff is a thief, and if he got caught he could hang.

So it’s not entirely remote.

It’s there, certainly.

His moods seem to change all the time. He says ‘’Sblood, I am as melancholy as a gib cat or a lugged bear.’ Where does that come from?

A morning hangover, I guess.

In the first scene we meet Falstaff and Hal, and the robbery is set up. Poins introduces it.

Yes. But there’s obviously a plan, because as soon as Poins comes on I say ‘Now shall we know if Gadshill have set a match.’ Really irritatingly, Shakespeare has named a character Gadshill, and the place where we do the robbery is also called Gad’s Hill, which is just infuriating.

Daft.

But the main thing is that Falstaff obviously wants Hal to come more under his influence, and being in the robbery would be a big step.

Is it the first time they’ve done that together?

Yes. I don’t think they’ve robbed before.

Act 2, Scene 2: the Gad’s Hill robbery. Coming back to the lighting (or lack of it) at the Globe, as it happens at night that’s surely one scene where you’d really want the stage to be pretty murky?

Well, it wouldn’t have been, originally. It’s just something you have to act.

So you pretended you couldn’t see anyone on stage?

Yes. Until they were really close. Or someone had a lamp. But there’s a double thing going on, because although you can’t see other characters on stage, you can see the audience. Falstaff talks to them when he first comes on.

Tell me about your attack on the travellers, followed by Hal and Poins robbing you. How was that staged? Was there much fighting? Later on, Falstaff looks as if he can handle a sword, but he doesn’t seem to put up much resistance in that scene.

Well, that’s to do with the darkness. Because if you can’t see, you don’t know what you’re doing with your sword. But there was a great deal of noise, and frightening people.

Did the staging of that scene make use of other levels?

Hal and Poins concealed their disguises down under the stage, and they went down into the yard when they hid.

So they were amongst the audience?

Yes. I came on for Gad’s Hill through the audience, and went up the steps on to the stage.

This business of acting darkness is an odd concept. Did you grope a lot, bump into things?

Yes. There was some wooden scaffolding which I started fighting against, thinking it was an enemy, and I tried at one point doing a somersault over it. But I didn’t do that for long because I realised my mind was making appointments that my body could no longer keep. There was a lot of not knowing quite what was happening, with Poins and Hal running around making a great racket, so we’d think there were loads of them.

You’ve known Poins for twenty-two years. You say ‘I am bewitched with the rogue’s company.’ But you’re slightly wary of him, I think. You don’t seem totally relaxed with him, as you are with Bardolph. Am I right about that?

There is some disagreement academically over whether Falstaff is talking about Poins, or else some of the lines refer to Hal. Poins is very good at organising robberies, but he’s a curious character.

He’s quite sharp, isn’t he.

Yes. And in a way he’s not unlike Falstaff. Considering who Falstaff was, I thought he obviously has no land, but he’s a knight. So what is he? The younger son of a younger son, perhaps? Somebody who’s gone into the army, done soldiering. And I guess we placed Poins very much in that kind of area, someone who’s come down in the world. But conversely, you could play Poins as someone who’s come up a bit.

He’s definitely several notches above Bardolph, isn’t he.

Oh yes.

Act 2, Scene 4: in the tavern after the robbery. Falstaff gives his own version of what happened. He describes fighting with first two, then four, then seven, then nine, then eleven ‘rogues… in buckram’. It’s absolutely hilarious, transparent nonsense. Does Falstaff expect to be believed? As an actor, how do you play that for truth?

Well, he almost convinces himself that it’s true, and it’s interesting that you mentioned the Blarney Stone. I think Ulysses in Homer’s Odyssey has a bit of the same economy with the truth. It often feels folksy and made up. He seems to be saying: ‘After I escaped from Troy I was lost on the seas for two years; I was lost on the sea for four years and then, after five years lost on the sea, I was on this island and there was a guy who was a giant, he was enormous, he was as tall as a house, as big as a cathedral, and he had one eye in the middle of his forehead – one eye, that’s all he had, in the middle of his forehead…’ So I guess I was imagining someone who, in the telling of a very tall tale, persuades himself that it’s true.

It’s a wonderful piece of theatre, based on pure fantasy.

We all know it’s completely untrue. But not nearly so enjoyable if Falstaff isn’t convinced he’s telling the truth. He believes Hal and Poins ran away – they were cowards and took to their heels. And again, I think the telling of it is like a compression of time. You know how, if one tells and retells an anecdote over a period of twenty years about something that really happened, it can often get more elaborate and funnier.

‘Was it for me to kill the heir-apparent?’ A brilliant improvisation. Falstaff would be a hell of a poker player, wouldn’t he.

I did take a pause before the line ‘By the Lord, I knew ye as well as he that made ye.’ That used to go down rather well. The audience absolutely loved Falstaff for it, because it’s so completely ludicrous. Harold Bloom refers to him as being a bit like an infant, because he’s got no super-ego. If you say to my younger son Thomas, ‘Tom, did you eat some of those sweets?’, ‘No, no,’ he’ll reply. ‘You did, didn’t you?’ – ‘No, no, I didn’t. No.’ – ‘You did, because I left you in the room and there were four sweets, and now there are only two. You’ve eaten two of them, haven’t you?’ – ‘No… Clanky did!’ So at certain times I thought of Falstaff as being incredibly infantile.

Before the play-within-the-play can start, they hear that the rebels are up in arms. Falstaff says ‘But tell me, Hal, art not thou horrible afeard?’ Does that threat from the outside world have serious weight?

Oh yes. I think so.

It doesn’t stop them going on with the play.

I think it is a real threat. The wars are about to take place, but they don’t destroy the evening yet.

The Hostess is in tears of laughter before the play even begins. What’s happening?

I think it’s just the sight of Falstaff with the cushion and the dagger.

What were you doing?

I had the cushion on my head for a crown, and a dagger for my sceptre. Also a change of voice, speaking posh. And she laughs because I’m calling her a queen, and including her in the play-acting. But she goes on laughing, so he tries to make her shut up first by being grand and regal, and then saying ‘Peace, good pint-pot; peace, good tickle-brain’, in a stage whisper. Then ‘Harry, I do not only marvel…’ back to the King. And it goes from one to the other.

The scene moves from a hilarious beginning to quite a harsh ending, with a catalogue of abuse from Hal. He calls Falstaff a ‘bolting-hutch of beastliness’, a ‘swollen parcel

of dropsies’, a ‘huge bombard of sack’ and so on. Depending on how Hal plays it, that can be amusing or hurtful. Does it get to you?

Our thoughts changed on that a bit and, perhaps, never quite settled. We never went for it being completely cold-heartedly cruel on Hal’s part. When it comes to insults, he’s not got a great deal of the variety. He just goes on saying: You’re fat; you’re really fat; God, you’re fat; you’re so fat. Falstaff can deal with that.

When he defends himself, it’s interesting that he denies being a ‘whoremaster’, which Hal has said nothing about. Then he goes on obsessively about banishment which, again, Hal hasn’t mentioned. What puts that into your mind?

Well, Hal, in the role of the King, does the reverse of what Falstaff playing the King has done. Falstaff has said: You’re with this appalling group of people, but there’s one good man among them, called Falstaff. So Hal does the opposite. He says ‘Thou art violently carried away from grace: there is a devil haunts thee in the likeness of an old fat man… that villainous abominable misleader of youth…’ You’re right: he doesn’t actually use the word ‘banish’, but I guess it’s implicit. Because what they’re playing around with is whether or not the King is going to tell Hal to change his ways and become a proper Prince. And that would mean not hanging around with this terrible crew, of which Falstaff is the leader.

Hal’s response to ‘Banish plump Jack, and banish all the world’ is very brief: ‘I do, I will.’ That can be much scarier. I wonder how he said it, and how you received it?

That’s something else that changed slightly, I would say, and became rather more serious as our run developed. He wasn’t being cruel, Hal, but he was saying this is inevitable. Then they’re interrupted by the sheriff at the door. This is a line that I took a while to understand: ‘Never call a true piece of gold a counterfeit; thou art essentially made, without seeming so.’

What do you reckon it means?

I think he’s telling Hal: You don’t seem like a Prince but, in essence, you are one. People aren’t always what they appear to be on the surface. So, by implication, he’s defending himself by using the Prince as an example.

Moving on to Act 3, Scene 3: Falstaff seems demoralised. He says ‘Am I not fallen away vilely since this last action?… Do I not dwindle?’ He laments his own thinness! Is it Hal’s treatment? Or Gad’s Hill?

Well, Gad’s Hill was the last action. They haven’t got the money. Hal has had to go to see the King. The war is about to start. And again, it’s the morning after.

Hmm yes, a slow start to the day.

This is where he shows a kind of Puritan streak: moments of self-flagellating guilt coincide with his hangovers. He needs a few to get himself going.

Bardolph says he’s too fat, and Falstaff then takes it out on Bardolph’s nose. He starts off with ‘I never see thy face but I think upon hell-fire’, and he goes on and on and on. On the page it seems quite unpleasant. Is it funny in performance?

I think it’s funny because it goes on and on and on. It’s completely unnecessary. But it’s the thing that wakes him up and gets him going. It’s like going to ballet classes for Falstaff, having a good workout: Ah there we are, that’s better – oh I’ve still got it, you know!

He feels energised after delivering a tirade of abuse. What was Bardolph’s reaction?

He’s the one who’s really drunk, much more than Falstaff. I used to be able to smell Bardolph. He’d sometimes come on behind me and I could smell that he was there.

That’s an interesting relationship. You bought Bardolph in St Paul’s, and have ‘maintained’ him for thirty-two years. He seems to be a mixture of servant and henchman and punchbag.

Yeah.

I’d say he’s the nearest Falstaff has to a wife. If he had a wife, she’d get similar treatment, wouldn’t she.

Yes, in a way, yes. Although of course the Hostess, Quickly (i.e. ‘quick lay’) wants to marry him in Part 2.

‘Enter Hal’, and Falstaff immediately livens up and becomes wittier. Hal says ‘I have procured thee, Jack, a charge of foot.’ Is that good news?

Well, it’s very good news that he’s got a charge. He’s got a job that will bring money, which gives him the power to recruit, and recruiting brings more money. It would be better if it was a charge of horse, because that would be less tiring. But it’s still pretty good, I think.

And war also gives chances to steal, doesn’t it.

Yes. But recruiting is the big thing. People had to bribe their way out of being soldiers, as happens in Part 2.

Act 4, Scene 2: a brief scene on the way to battle. Falstaff tells Bardolph to fill a bottle of sack. Bardolph says ‘This bottle makes an angel’, presumably meaning the sum of

money he is owed by Falstaff, who answers ‘An if it do, take it for thy labour; and if it make twenty, take them all.’ Have you any idea what that means?

We couldn’t make it work at all. After I’d sent him off to get the bottle of sack, I’d pull a full one out of my satchel and start drinking it. And that was when I had my potted meat.

Then you have your soliloquy about the ragamuffin soldiers…

And that’s all about making money from bribery.

It’s pretty callous, isn’t it. On the page, again, it’s not particularly amusing.

No, it isn’t. Although there’s a comic-riff element about how appalling they are: This guy saw them and said I must have got dead people from gibbets. But the reality of course is completely unemotional. He’s deeply unsentimental about war, and about heroism. When the Prince says ‘I did never see such pitiful rascals’, Falstaff’s attitude is ‘Tut, tut, good enough to toss; food for powder, food for powder. They’ll fill a pit as well as better. Tush, man, mortal men, mortal men.’ Which is very chilling. But it’s also: Don’t give me any of this bullshit about honour; this is what war is. What are these foot-soldiers going to do? They could be really good men, and they’ll get killed all the same. That, to me, was the voice of someone who’s seen quite a lot of war, and who is basically just intent on surviving it.

So he’s not especially proud, or ashamed. It’s matter-of-fact.

Well, it’s hard-nosed and real. There are certain things Falstaff says, especially in the ‘honour’ speech later on [5.1], but also here, where you think this could be a play by Brecht. He starts inhabiting another type of character: the clown who undermines the hero. The Good Soldier Schweik gives that view of honour and heroism.

You have a non-combative couplet at the end of the scene: ‘Well, / To the latter end of a fray and the beginning of a feast / Fits a dull fighter and a keen guest.’ Presumably Westmoreland has exited by then.

Yes, I said them to the audience. And I remember, to my shame, we added in some bits. Because Falstaff had been talking about soldiers that the audience can’t see, Bardolph and I did a bit of cod parade-ground drill at the beginning. It was like Sergeant Bilko – remember Phil Silvers? It was that kind of stuff. There was loads of it when we first came on. And then I did more on my exit, urging some of the audience to come up.

And did they?

No, no, no. I didn’t actually try to drag them up on stage.

You made a token effort.

Yes. So the scene was book-ended by Bilko, whom I feel Shakespeare would have loved.

Act 5, Scene 1: the battle is looming and you’re with the King – and virtually silent for 120 lines. That’s unusual for Falstaff.

It’s strange that he’s there, isn’t it.

How did it feel to be an onlooker for so long? What were you doing?

I was just standing there, being confirmed in my view of all this stuff, these arguments that go on and on and on.

You have one line about Worcester: ‘Rebellion lay in his way, and he found it.’

I suppose I was thinking these people are determined to have a war, and they’ll make sure to find a pretext.

The King goes off, and Falstaff’s courage seems to evaporate: ‘I would ’twere bed-time, Hal, and all well.’ He’s suddenly vulnerable. It’s quite a change after all the braggadocio.

Yes, it’s kind of him speaking as a child. But then he really gives us the truth in the magnificent ‘honour’ speech.

Of all his soliloquies, it feels almost like a duologue with the audience, in the way it goes question/answer, question/answer. ‘Can honour set a leg? No. Or an arm? No.’ Could it be done inviting the audience to answer you?

You could do, I suppose. I think all his soliloquies very much acknowledge the presence of the audience. But you’re absolutely right, this one especially so. He assumes that the audience are 1,500 Falstaffs, 1,500 people in complete sympathy with him. I seek their support and agreement. On other occasions I might perhaps want to outrage or challenge them, or amuse them. I’m not amusing them here though.

Is this more the speech of a coward or a pragmatist?

I think it’s the speech of an old soldier who’s a pragmatist. It’s funny how people want to say Falstaff is a coward. Hotspur says: We’ve hardly got any men, but it doesn’t matter because we can all die gloriously and it’ll be wonderful. It’s utterly callous, the way Hotspur thinks of the lives of other people in relation to his own honour and fame. It is much, much crueller than anything Falstaff does. Falstaff is saying that kind of heroism is complete bullshit.

Then you get a short scene in the middle of battle, Act 5, Scene 3. Falstaff says ‘I have paid Percy, I have made him sure.’ Not a word of truth – once again a complete fabrication! What makes him say that?

Well, it was worth a go! After Hal’s exit, Walter Blunt was lying dead, and I stole his ring. That was a piece of business I nicked from another actor – Gambon, I believe. I thought: Oh, that’s a good idea.

You stole a ring off Blunt’s corpse?

Yeah. Sometimes audience members were really shocked at that, especially American students. They’d go [Intake of breath.] Ohh! – because I’d taken the ring off a dead body. I thought: Great, fantastic!

Earlier there’s a little gag where Falstaff offers Hal his pistol, which turns out to be a bottle of sack. On the face of it, an ill-timed jest. Or was he kindly offering Hal a drink?

I’d say the former. Falstaff is saying: You can’t have my sword, because I might need it to protect myself. But Hal is in some desperation, so it’s a very ill-timed jest. I guess it’s part of the madness of battle.

Act 5, Scene 4. The whole play has been leading up to the Hal/Hotspur confrontation. Hal says ‘Two stars keep not their motion in one sphere.’ Shakespeare brilliantly brings Falstaff on, right in the middle of their fight, followed by Douglas who apparently kills him. How was your sword-fight with Douglas?

Well, it was brief. At the earliest opportunity I got some blood and pretended to be dead.

Smeared yourself?

Yes. I got plenty on my face, to make sure it would read. And then later, after Hal’s exit, I cheated a bit. I said to the audience: ‘It’s blood!’

In what way ‘cheated’?

I said ‘It’s blood’ instead of ‘’Sblood…’, before ‘’Twas time to counterfeit’ – I took the bottle out and poured more blood over my hand. I was explaining to them that it was just the fake blood that every proper soldier should carry around with them, in case they need to play dead.

How convincing a corpse were you? Did anyone realise you were counterfeiting?

I wanted to look like a real corpse.

There are things Hal says over your apparent corpse. I can imagine some Falstaffs might react to get a cheap laugh.

I thought it was really important that if people hadn’t seen the play before, they should think Falstaff is dead. If you imagine the first time the play was performed, it must have been the most extraordinary coup when he got up. I left quite a pause after Hal went, and there was some noise of the battle off stage. Then I said ‘Embowelled?’ while I was still lying there facing upstage. That got a great response. But the speech afterwards was very serious. The vital thing is to try and live, as he says earlier…

‘Give me life.’

‘Give me life.’ Yes. He says that over the dead body of Blunt. Throughout the battle he’s saying the important thing is to survive. It’s clever and witty. ‘Counterfeit? I lie, I am no counterfeit: to die, is to be a counterfeit… But to counterfeit dying, when a man thereby liveth, is to be no counterfeit, but the true and perfect image of life indeed. The better part of valour is discretion, in the which better part I have saved my life.’ I think there’s a deep philosophical truth for Falstaff in there.

There’s a cheeky moment when he says ‘Nobody sees me.’ It must be fun saying that to a packed audience of 1,500 people.

Yes, it’s wonderful.

You get to pierce Percy after all: once he’s dead, you stab him in the thigh.

Well, it would be cutting an artery. If you were a clever fighter that might be what you would do, to hobble someone so that you could kill them.

Hal comes on and says ‘Art thou alive, / Or is it fantasy that plays upon our eyesight?’ Is that tongue-in-cheek?

Well, he believed that Falstaff was dead. I suppose it’s one of the things you might say: My God, is this really you? I thought you were in Italy. Perhaps I’m asleep and dreaming, and I’m about to wake up… But at that moment when they came on, I was trapped under the dead Hotspur.

Oh really?

Yes. I used to try and lift him up and he would fall on top of me. During the early previews I was lifting Hotspur on my own with various bits of comic business, but it was a disaster. I did my back in, and became completely poleaxed. On the Sunday I woke up feeling really knackered, with two shows that day, and there were no understudies. So I just had to take painkillers and wear a support belt, and go on walking with a stick. It meant I could no longer lift Hotspur on my own, so Bardolph came on to help. That was when he would enter behind me silently, and I’d smell that he was there. It had a pay-off in Part 2 when he did the same thing after the ‘sack’ speech, and again I’d smell his presence.

So you struggle to your feet and throw Hotspur down and say ‘There is Percy.’ I love this: ‘We rose both in an instant, and fought a long hour by Shrewsbury clock.’ It’s a terrific bluff, isn’t it.

Brilliant. It’s the kind of detail that makes a lie perfect. And yes, once again gambling comes to mind. Mike Gambon told me a story about a radio director he hated who offered him a play he didn’t want to do, but he hadn’t said yes or no. The director came into a pub where he was and said, ‘Oh hello Michael, did you get the play?’ And Michael instantly said ‘Oh, God, so sorry. I don’t act any more. Didn’t you know? Oh dear, no, I’ve stopped acting.’ And the director’s going ‘What? What?’ – ‘Yeah. No, I’ve given it all up. I run a secondhand car showroom in Walthamstow.’ And Mike said it was the Walthamstow detail that got him. It’s just the same with the Shrewsbury clock.

Hal says ‘If a lie may do thee grace, / I’ll gild it with the happiest terms I have.’ Which is amazing generosity, isn’t it.

It really is. There is a danger-point here because Lancaster’s on stage as well, who becomes very much Falstaff’s enemy. And in front of Lancaster, Hal lets Falstaff take the credit.

You’ve got a lovely upbeat final line: ‘If I do grow great, I’ll grow less, for I’ll purge, and leave sack, and live cleanly…’

‘…as a nobleman should do’!

Tell me another! Moving on to Part 2… Are there particular differences between Parts 1 and 2 of Henry IV?

Falstaff doesn’t see nearly as much of Hal. Shakespeare keeps them apart because, although Falstaff isn’t aware of it, the relationship is inevitably moving towards his rejection.

It seems that Falstaff has an improved status.

Yes. We put in a song: ‘The Ballad of the Battle of Shrewsbury’.

Did you indeed!

Yes. Falstaff had written it about his own bravery at the battle. That’s what people did – they had ballads celebrating their heroic deeds. He talks about it later on.

When was it performed?

People started singing it during the change from Scene 1 into Scene 2. And then I made an entrance into what was a marketplace, singing a verse. Shakespeare omitted to write this, but the spirit of Will Kempe was with us.

So it’s established that you’re the hero of Shrewsbury.

Yeah. He’s trying to puff himself up, give it everything. The Lord Chief Justice also refers to it: ‘Well, I am loath to gall a new-healed wound. Your day’s service at Shrewsbury hath a little gilded over your night’s exploit on Gad’s Hill. You may thank the unquiet time for your quiet o’er-posting that action.’

It’s a bit odd because ‘Your day’s service at Shrewsbury’ is rather less than ‘Your heroism in slaying Hotspur’. That seems too little praise if people really believe Falstaff slew Hotspur, and too much if they don’t. Nonetheless he’s given this elevated status.

Well, yes.

Did you have costume and make-up changes for Part 2?

Certainly a costume change. I was in much better gear until we went to war, when I was wearing my old campaign stuff.

There’s an immediate reference to Falstaff’s poor health. And he sounds a bit rueful: ‘I am not only witty in myself, but the cause that wit is other men.’

You certainly could play that. But this scene with the Lord Chief Justice is so brilliant, I resisted much focus on the illness, the getting old. What has he got?

Pox and gout.

He doesn’t dwell on it. He hasn’t got a lot of money and he’s still on the make. But he’s come up in the world a bit, and he’s trying to push his hero-of-Shrewsbury image. I found the stuff with the Lord Chief Justice absolutely terrific. ‘My good lord! – ’ it’s wonderfully funny – ‘I am glad to see your lordship abroad. I heard say your lordship was sick; I hope your lordship goes abroad by advice; your lordship, though not clean past your youth, have yet some smack of age in you, some relish of the saltness of time…’ It’s so dazzlingly fast.

Is that how you played it, at breakneck speed?

Yes.

He basically bullshits the Lord Chief Justice out of his stride, doesn’t he.

He does, yes. During this exchange an Elizabethan audience would have been aware of another play, The Famous Victories of Henry V, which was written only a few years earlier. In it Hal gives a box on the ear to the Lord Chief Justice, who imprisons him.

That’s mentioned, isn’t it.

It’s mentioned later on, but it doesn’t have the impact of a live scene. Nonetheless what must be at the back of the Lord Chief Justice’s mind is what will become of him after the King dies. As soon as that happens he says words to the effect of ‘I’m fucked’. And I think Falstaff is aware of the shaky relationship the Lord Chief Justice will have with Hal when he becomes King.

Or so he hopes.

Yes.

The Lord Chief Justice later snaps, and delivers a catalogue of Falstaff’s infirmities, which seems to be water off a duck’s back. He’s Teflon-coated! And then, claiming to be ‘in the vaward of… youth’, he says ‘I was born… with something a round belly.’ Whereas in Part 1 it was ‘When I was about thy years, Hal, I was not an eagle’s talon in the waist’ [2.4]. He just says whatever suits him.

Yes, he does. It’s his way of saying: Look, I was born like this; actually I’m only seventeen years old. But also what’s brilliant is that he says: Enough of this talk. ‘To approve my youth further, I will not: the truth is, I am only old in judgement and understanding; and he that will caper with me for a thousand marks, let him lend me the money, and have at him.’

He tries to borrow a thousand pounds from the Lord Chief Justice, who he must know is the last person in the world who will lend it to him. Falstaff just enjoys winding him up, I suppose.

Yes. But he’s also saying: I need money because I’m going to the wars; you’re merely arsing around here putting people in prison. The Lord Chief Justice exits, saying ‘Fare you well. Commend me to my cousin Westmoreland.’ And Falstaff goes ‘If I do, fillip me with a three-man beetle.’ [Roger delivers the line with enormous relish.] I just love that: Smack me over the head with a massive hammer!

Act 2, Scene 1. Officers are sent to arrest Falstaff, and they fight. He now has a diminutive Page, who joins in with these great lines: ‘Away, you scullion! you rampallian! you fustiliarian! I’ll tickle your catastrophe!’ The Lord Chief Justice returns, and seems much more in command than he was in the first scene.

He finds me brawling.

So you’re more on the defensive.

I have to do a very swift job on the Hostess.

Meaning?

Well, she’s trying to get me arrested. She complains to the Lord Chief Justice with a long rigmarole about how she lent me money and I promised to marry her. I take her aside. Master Gower talks to the Lord Chief Justice for two lines, and immediately I’m persuading her to lend me more money.

He’s outrageous.

He obviously must have charms. Maybe he is good in bed.

In any case, she can’t resist him. In Part 1 she had a husband.

Yes.

But now she’s widowed, presumably, and hopes to marry you. She wants to become Lady Falstaff.

Yes. And to pursue that end she is willing to get me a whore.

‘Will you have Doll Tearsheet meet you at supper?’ she says. She doesn’t mind if you shag Doll, as long as you marry her.

No.

Act 2, Scene 4. Another wonderful tavern scene. It’s after dinner, and everyone has had plenty to drink.

We’ve had a lot, I think, because Doll Tearsheet is sick. And she can probably put a fair amount away. There are some quite vicious insults with Doll, the way it can get after one too many. ‘Your brooches, pearls, and ouches’ are the jewels of her venereal disease.

Pistol arrives outside. Falstaff calls him ‘Mine ancient’. What is an ancient?

Well, Othello refers to Iago as his ancient, doesn’t he. It’s like his non-commissioned officer, I think.

It’s odd: no one wants Pistol around because he’s known to be a complete pain in the arse. But Falstaff insists on letting him in, and then kicks him out again within two minutes.

I know, it’s very strange. I think Falstaff finds Pistol quite amusing for a while – in the way he disrupts everything, and upsets Mistress Quickly. But then he soon goes too far, and they have to get rid of him. I assumed all that was to do with a level of drunkenness in which things can change very quickly.

He’s the one character who’s even more outrageous than Falstaff, isn’t he.

He’s just weird. Really destroyed brain cells.

Does Falstaff feel at all upstaged by Pistol?

Well, luckily for those of us who play Falstaff, no one understands what Pistol is talking about, least of all Pistol.

‘Enter Musicians’: what kind of music did they play?

It was like sleazy Elizabethan jazz, on period wind instruments. It was terribly, terribly good. I loved it.

Falstaff says ‘Sit on my knee, Doll.’ And the scene seems to move into a calmer mode.

Yes, it becomes an opportunity. Just before that, I’ve rescued them from the terribly dangerous Pistol. Falstaff says ‘A rascally slave! I will toss the rogue in a blanket.’ And Doll goes ‘Do, an thou dar’st for thy heart. An thou dost, I will canvas thee between a pair of sheets – ’ which sounds like an invitation. Then the sleazy jazz. ‘Sit on my knee, Doll’ is the start of some heavy petting. It’s foreplay, I suppose, because we haven’t got anywhere yet. So although it was simple, it was very sexual.

But then ‘Enter Hal and Poins unseen’, and Doll seems to give perfect cues for Falstaff to betray them. It’s as if she knows they’re eavesdropping.

Oh we played it that she knew they were there, and this was a prearranged set-up.

And yet at the end of the scene she’s crazy about Falstaff.

Yes. But it’s not as if this trick is supposed to destroy Falstaff – it’s just a bit of fun, a prank to catch him out. And there were so many twists and turns in this scene that, again, I took it as part of the fact that everyone’s had a great deal to drink. I guess this is the only scene in which Falstaff is really quite drunk.

So searching for a coherent, linear path through it is a waste of time.

Well, yes, things can shift. She can be part of this trick, but it doesn’t mean that she isn’t going to be terribly sentimental about him leaving. And he’s heroically going off to the war, and playing that to the hilt.

Poins says ‘Is it not strange that desire should so many years outlive performance?’ Can Falstaff still get it up, do you think?

I think he probably can, you know. And if on occasions he can’t, he’s got other things in his armoury.

Then it all goes wrong when they reveal themselves. Hal says ‘You whoreson candle-mine you, how vilely did you speak of me even now.’ He seems to be genuinely angry, and Falstaff rather stammers, doesn’t he. He just says ‘No abuse… No abuse… No abuse, Hal… No abuse, Ned.’ He seems to flounder.

He does a bit, yes. But the audience liked ‘I dispraised him before the wicked, that the wicked might not fall in love with thee; in which doing, I have done the part of a careful friend and a true subject.’ We used to get a good response on that. But you’re right, he’s not quite as brilliant as he was in Part 1, or in the first part of this play when he’s dealing with the Lord Chief Justice.

Hal doesn’t buy it, does he. And that’s the last time the two of you meet, isn’t it, until the final scene of the play.

Hal doesn’t buy it. But all I can say is that playing it, it didn’t seem over-serious. It didn’t feel like the beginning of the end.

You couldn’t do the rest of the play with that foreknowledge, could you.

No.

There’s a beautiful end to the scene with Doll saying ‘I cannot speak; if my heart be not ready to burst – Well, sweet Jack, have a care of thyself.’ Then Falstaff calls for her to come to him, and they have a quick one before he goes off to war. Was that the interval? It feels as if it might be.

I think we took the interval after the next scene.

Act 3, Scene 2 is a total change, down to the West Country. Falstaff is a Londoner through and through, isn’t he. Were you a fish out of water?

Well, no. You’re right that he is a London man, but I think he’s used to being a recruiting officer, and travelling is part of the job.

You knew Shallow ages ago, when you were young lads around the Temple. How much are you involved with him now? Is he a friend, or just someone from your past?

Someone I knew a long time ago. He was older than me.

You don’t seem to want to linger. Rather surprisingly, you turn down the offer of dinner.

That’s right. He wants to get his recruits and move on. It’s funny. Shallow’s very anxious for him to stay – I suppose for news of court, the link with the court. But at the end of the scene Falstaff makes an appointment with the audience. He says: If all goes well I’ll come back here and get my thousand pounds.

He hasn’t come with the express purpose of getting a grand, has he.

No. But when he arrives he sees that Shallow lives very well. He’s got land and servants.

He doesn’t seem to enjoy Shallow’s reminiscences very much. And yet he’s got this wonderfully haunting line, ‘We have heard the chimes at midnight, Master Shallow.’

It’s just brilliant. The thing is, he goes with Doll in a desperate attempt to cling on to some sense of youth, or youth through shagging. Whereas with Shallow, everything he says, and every person he mentions, reminds Falstaff of how old he is, and how much nearer death than he would like to be. Just before that, they’re talking about Jane Nightwork the prostitute, and Silence says ‘That’s fifty-five year ago.’ Didn’t the ‘chimes at midnight’ refer to a clock that struck somewhere in Clement’s Inn? I think they were specific chimes, so there is a literalness to it. Perhaps Falstaff is beginning to hear the clock striking the last hour of his life.

At the end of the scene you have a soliloquy about the young Shallow – as a lecherous scarecrow, who has become a landed gentleman.

There’s disbelief that here am I, Sir John Falstaff, and here’s this pathetic beanpole of a man whom no one admired for anything at all. He now has far more substance than I have in terms of living well and being stable. He possesses land and beefs, and a thousand pounds.

Act 4, Scene 3, on the field of battle. The famous rebel John Coleville surrenders without a blow being struck. Is that because you’re the reputed Hotspur-killer? Did you act very fiercely?

No, no, no. He surrenders because they’re all fleeing, the whole rebel army. Coleville says later:

I am, my lord, but as my betters are

That led me hither. Had they been rul’d by me,

You should have won them dearer than you have.

In other words: If I’d been in charge, we’d have had a battle. But Coleville is yielding because their army has disbanded. There’s nothing to be done.

Lancaster is totally unimpressed by Falstaff, isn’t he, and accuses him of malingering.

Once again Falstaff bigs it up. He answers ‘Do you think me a swallow, an arrow or a bullet?… I have speeded hither with the very extremest inch of possibility; I have foundered nine score and odd posts; and here, travel-tainted as I am, have, in my pure and immaculate valour, taken Sir John Coleville of the Dale, a most furious knight and valorous enemy.’ It’s quite brilliant stuff.

Lancaster cold-heartedly condemns Coleville and his confederates to death. His problem, of course, is that he’s a teetotaller.

That’s right. ‘He drinks no wine.’

And you’re into the sherris-sack speech.

I used to drink a bottle of sack during it. My belt carried the nice little horn cup, so at various points I’d be able to refresh myself.

Act 5, Scene 1: back in Gloucestershire with Shallow and Silence. Again, you seem to be in a hurry to get away. But you’re persuaded not to.

Well, I played that as not really wanting to get away, because I’d made an appointment with the audience to come back. The last thing I said to them was: ‘I’ll go through Gloucestershire, and there will I visit Master Robert Shallow. I have him already tempering between my finger and thumb, and shortly will I seal with him’ [4.3].

So you’ve come back down for the money.

Yeah. What I can get.

The third scene running that ends with a soliloquy.

We cut a lot of these – in particular, references to Shallow being as thin as a ‘hermit’s stave’, and so on, because our Shallow wasn’t particularly thin. Bill Gaunt was absolutely wonderful, but he’s not the thinnest person in the world… Going back to the lighting, there’s a beautiful moment every evening at the Globe when daylight is fading, and they very gradually bring on floodlights. It used to happen about the time of this scene. They light the audience as well as the actors, and when you still have the remains of daylight with the artificial lights coming on, it’s stunning.

Act 5, Scene 3: after dinner with Shallow and Silence, who are both evidently as high as kites. How’s Falstaff doing?

Pretty well, but not nearly as drunk as them. He doesn’t say a great deal in this scene. It’s a kind of waiting scene.

And Davy is busy bonding with Bardolph.

Yes.

Shallow’s going on about caraway seeds and last year’s pippins. I shouldn’t think you’re very interested in all that, are you.

I’d enjoy eating them, but methods of growing them wouldn’t be of particular interest to me, no.

Caraway seeds are supposed to be an antidote for farting, of course.

Are they? I wish I’d known that.

You didn’t have any farting gags?

No, we didn’t have any farting gags. That would be vulgar, Julian!

Enter Pistol –

Actually, we did have one farting gag. But talking of the music, it occurred to me that there hadn’t been any for a long time, apart from ‘The Ballad of the Battle of Shrewsbury’. Falstaff doesn’t have the same relationship to music in the second play as he does in the first, which is another thing that Shakespeare foolishly left out. In this scene Falstaff is uncharacteristically silent – he’s not going off on great comic riffs or anything, but just being there in a bucolic kind of way. So I took out some pan pipes and played them, quietly, by myself. Which I thought might just hit the retina of the audience a bit.

Did Shallow and Silence appreciate that?

Yes.

Although you were upstaging them!

No, no, no. I took the pipes out and played them during a little lull.

Silence sings snatches of song as well, doesn’t he.

Yes.

Enter Pistol with news from court. He says ‘Sweet knight, thou art now one of the greatest men in this realm.’ You would surely have a pretty good idea what that means?

It’s funny, he takes ages to come out explicitly with the news.

He goes through his usual load of fustian bollocks, but then he finally says ‘Sir John, thy tender lambkin now is King, Harry the Fifth’s the man.’ So then you really think the sky’s the limit, don’t you.

And the pan pipes became a sort of weapon.

Really? How so?

Well, it was just in the way of holding them. [Roger holds his hand aloft like someone brandishing a sword, triumphantly.]

I see. A sort of token, an emblem. And what’s touching at that moment is that we see Falstaff at his most generous, don’t we. He wants to give everything to everybody.

Oh yes. He wants to be the great distributor of largesse. That is ultimate power I suppose, isn’t it, the giving of life and munificence.

Into Act 5, Scene 5: the final scene, with Hal newly crowned King. You’ve had no time to change, and arrive ‘stained with travel and sweating with desire’ to see Hal. What did you look like?

Still in campaign gear. I didn’t have armour on, but I had the trousers and jerkin that I’d worn under my breastplate.

The usual outfit, but manked up a bit.

Yeah.

The excitement is intense. Hal appears and Falstaff shouts ‘My King! My Jove! I speak to thee, my heart!’ What does Hal say?

‘I know thee not, old man. Fall to thy prayers. / How ill white hairs become a fool and jester!’

Can you describe your reaction?

Well, it went through stages. There was a moment of disbelief: Is this really true? And then Hal says:

So surfeit-swell’d, so old and so profane…

Leave gormandising; know the grave doth gape

For thee thrice wider than for other men.

And I thought: Oh, so you’re just going on about my fatness again, that’s all, it’s going to be alright. But then he goes on ‘Reply not to me with a fool-born jest’, and the rest of the speech, very slowly and surely, absolutely puts the knife in. There’s the realisation that this really is it, he’s banishing me. Hal tempers it just a bit by saying:

For competence of life I will allow you,

That lack of means enforce you not to evils;

And as we hear you do reform yourselves,

We will, according to your strength and qualities,

Give you advancement.

But it’s cold comfort. He’s saying: If you behave well, maybe you’ll get a really minor position somewhere, or you’ll be able to come within five instead of ten miles of me. It’s nothing. For me, it was very much like a death. And after that I tried to achieve a sense of him suddenly becoming really, really old.

Deflated.

Yes. Completely.

He tries to tough it out, doesn’t he, and put on a brave face.

Yes.

But he doesn’t convince anybody, least of all himself, I suppose.

No. No, he doesn’t convince himself at all. He tries to hang on to Shallow’s money. And the end is really quite harsh. Because he says ‘Go with me to dinner. Come, Lieutenant Pistol; come, Bardolph.’ Then, bang! Over the next half-dozen lines the Lord Chief Justice, Prince John and officers come on, and they’re all arrested and taken off to prison. It’s chilling. It exemplifies what Graham Holderness said about a medieval chivalric prince and a raggletaggle band of Elizabethan soldiers, and a creature from immemorial carnival. And you get what scholars call the ‘Shakespeare Moment’, a crossroads where the banishing of the old world meets the early modern world of realpolitik.

Can you conclude by summarising Falstaff’s journey through these two plays. What does he learn? What does he win? What does he lose?

I would say he loses absolutely everything. And although in the epilogue it’s promised that we’ll see him again, we don’t. The next time we hear of him is in Henry V, when his death is referred to. Mistress Quickly says ‘I put my hand into the bed and… felt to his knees, and so up’ard and up’ard, and all was as cold as any stone’ [2.3]. The woman who wrote Filthy Shakespeare thinks it means that she was intending to jerk him off. Other people believe it refers to the death of Socrates, that there’s a similarity in the descriptive terms.

Does he learn anything?

He learns that he’s lost. It’s too late for him to think: Oh right, I’ll go and be a carpenter then, or do something else more practical. He learns that he’s lost everything, that he’s just going to dwindle and die, and not be friends with the Prince and not be the greatest man in the land.

You had a terrific curtain call.

We did a jig, just as they used to do in Shakespeare’s time. At the end of each play, even Titus Andronicus or King Lear – first of all, clowns would come on and do some funny stuff, and then the whole company would do a dance.

At the end of all of his plays?

Yes. So at the Globe nowadays, you don’t get clowns doing comic turns, but there’s always a dance which segues into the curtain call. We did a particularly good one at the end of Part 1, it was absolutely wonderful. If you look at the DVD you can see it, and I think there might even be a little bit of the jig on YouTube. It was just deeply eccentric and wacky. If you did the same thing at an indoor theatre it would seem self-conscious and showbizzy whereas there, outdoors, it was perfect.

Did it get the audience involved?

What, get the audience dancing?

Yes.

No. It didn’t get them dancing, but they’d cheer and clap. They would really, really rock on certain occasions, absolutely brilliantly. You could barely hear the music sometimes, the roaring was so loud.

![]()